Report on Regional Workshop on Chainsaw Milling, Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy

REPUBLIC OF GHANA GHANA FOREST AND WI LDLIFE POLICY Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources Accra- Ghana 2012 Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy © Ministry of Land and Natural Resources 2012 For more information, call the following numbers 0302 687302 I 0302 66680 l 0302 687346 I 0302 665949 Fax: 0302 66680 t -ii- Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ... ... .. .............. .. ..... ....... ............ .. .. ...... .. ........ .. vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ................................................................. .......................... viii FOREWORD ........................................................................................... ...................... ix 1.0 PREAMBLE ............ .. .................................................................. .............................. ! 2.0 Overview Of Forest And Wildlife Sector ..... ............................ .................... ... 3 2 .1 Forest and Wildlife Conservation 3 2.1.1 Forest Plantation Development 4 2.1.2 Collaborative Forest Management 5 2.2 Challenges and Issues in the Forest and Wildlife Sector 2.3 National Development Agenda and Forest and Wildlife Management 2.4 International Concerns on the Global Environment 9 3.0 THE POLICY FRAMEWORK ......................... .. ............................................ ........ 10 3.1 Guiding Principles 10 4 .0 THE FOREST AND WILDLIFE POLICY STATEMENT ............................ ......... 12 4 .1 Aim of the Policy 12 4.2 Objectives of the Policy 12 5.0 Policy Strategies ............ -

Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance

ETF r n i s s u e N o . 5 5 , m a R c h 2 0 1 4 n E w s 55 RodeRick Zagt Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance EuropEan Tropical ForEsT ResEarch Network EuRopEan TRopIcaL ForesT REsEaRch NetwoRk ETFRN News Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance IssuE no. 55, maRch 2014 This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European commission’s Thematic programme for Environment and sustainable management of natural Resources, Including Energy; the European Forest Institute’s Eu REDD Facility; the German Federal ministry for Economic cooperation and Development (BmZ); and the Government of the netherlands. The views expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of ETFRn, Tropenbos International, the European union or the other participating organizations. published by: Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands copyright: © 2014 ETFRn and Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands Texts may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, citing the source. citation: Broekhoven, Guido and marieke wit (eds.). (2014). Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance. Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands. xx + 212 pp. Editors: Guido Broekhoven and marieke wit Final editing and layout: Patricia halladay Graphic Design IsBn: 978-90-5113-116-1 Issn: 1876-5866 cover photo: women crossing a bridge near kisangani, DRc. Roderick Zagt printed by: Digigrafi, Veenendaal, the netherlands available from: ETFRn c/o Tropenbos International p.o. Box 232, 6700 aE wageningen, the netherlands tel. +31 317 702020 e-mail [email protected] web www.etfrn.org This publication is printed on Fsc®-certified paper. -

Human-Wildlife Conflicts

Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Human-Wildlife Conflicts Editor: M. Laverdière Assistant Editors: L. Bakker, A. Ndeso-Atanga FAO Regional Office for Africa [email protected] www.fao.org/world/regional/raf/workprog/forestry/magazine_en.htm FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Accra, Ghana 2007 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Communication Division, FAO,Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected]. ©FAO 2007 Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Table of Contents Page Editorial 1 News News in Africa 2 News Worldwide 3 FAO News 5 Thematic News in Africa 6 Thematic News Worldwide 6 Special Feature Human-Wildlife Conflict: A Case for Collaboration 8 Madden, F. -

Forest Investment Program Ghana

FOREST INVESTMENT PROGRAM GHANA: PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP FOR THE RESTORATION OF DEGRADED FOREST RESERVE THROUGH VCS AND FSC CERTIFIED PLANTATIONS USD 10 million May 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I ACRONYMS II COVER PAGE 1 BACKGROUND 4 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 11 FIT WITH FIP INVESTMENT CRITERIA 15 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 19 ANNEX 1: INVESTMENTS IN SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY – A BRIEF PRESENTED TO AFDB’S CREDIT COMMITTEE 19 i ACRONYMS AfDB African Development Bank CIF Climate Investment Funds DSCR Debt Service Coverage Ratio ESAP Environmental Assessment Procedures FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FC Ghana Forest Commission FIP Forest Investment Program FSC Forest Stewardship Council FWP Forest and Wildlife Policy 1994 GoG Government of Ghana IP Investment Plan ISS Integrated Safeguards System ITTO The International Tropical Timber Organization NFPDP National Forest Plantation Development Program PPP Public-Private Partnership REDD+ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation VCS Verified Carbon Standard ii COVER PAGE Public-Private Partnership for the restoration of Degraded Forest Reserve through VCS and FSC Certified Plantations. 1. Country/Region: Ghana 2. CIF Project ID#: (Trustee will assign ID) 3. Source of Funding: FIP PPCR SREP 4. Project/Program Title: Ghana: Public-Private Partnership for the restoration of Degraded Forest Reserve through VCS and FSC Certified Plantations. 5. Type of CIF Investment: Public Private Mixed 6. Funding Request in million Grant: Non-Grant: USD equivalent: USD 10 million Concessional Loan 7. Implementing MDB(s): African Development Bank 8. National Implementing Not Applicable. Agency: 9. MDB Focal Point and Headquarters- Focal Point: TTL: Project/Program Task Gareth Phillips Richard Fusi [email protected] / Team Leader (TTL): [email protected] / Leandro Azevedo [email protected] 10. -

A Review of Policy Ad Regulatory Discourses O Timber Legality

One hundred years of forestry in Ghana: A review of policies and legislation K. A. Oduro et al. OE HUDRED YEARS OF FORESTRY I GHAA: A REVIEW OF POLICY AD REGULATORY DISCOURSES O TIMBER LEGALITY K. A. Oduro 1, E. Marfo 1, V. K. Agyeman 1 and K. Gyan 2 1CSIR-Forestry Research Institute of Ghana, University Post Office Box UP 63, KUST, Kumasi Ghana 2Ministry of Lands and atural Resources, Accra Ghana Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] ABSTRACT Ghana has seen incremental shifts in forest policy, legislation and management approaches in the last one hundred years. Information on forests through time and knowledge of policy evolution, laws, and participants and institutions involved in the policy process is important to deal with complexities associated with timber legality and trade. This paper reviews the evolution of forest policies and regulations on timber legality in Ghana using a historical discourse analysis. It characterises the regulatory discourses of successive forest policies and legislations and the extent to which policy and policy instruments, particularly on trade of legal timber, reflect the hard, soft, and smart regulatory discourses. The paper shows that until the mid-1980s Ghana’s timber regulation policies had been characterized largely by state control using top-down management and hard law regulations. The mid- 1980s and the early 1990s represent an interface between the softening of state control and the emergence of de-regulation and soft law discourses. The 1994 Forest and Wildlife Policy reflected this interface calling for improved collaboration with communities and market-driven strategies to optimize forest use. -

Using Portable Sawmills to Produce High Value Timber from Farm Trees in the Semi-Arid Zone

Using portable sawmills to produce high value timber from farm trees in the semi-arid zone A report for the RIRDC/ Land & Water Australia/FWPRDC/MDBC Joint Venture Agroforestry Program and the Natural Heritage Trust by P. Blackwell & M. Stewart October 2003 RIRDC Publication No 03/046 RIRDC Project No PN99.2001 © 2003 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 0642 58614 4 ISSN 1440-6845 Using portable sawmills to produce high value timber from farm trees in the semi-arid zone Publication No. 03/046 Project No. PN99.2001 The views expressed and the conclusions reached in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of persons consulted. RIRDC shall not be responsible in any way whatsoever to any person who relies in whole or in part on the contents of this report. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Philip Blackwell Mark Stewart Forestry Campus Forestry Campus University of Melbourne University of Melbourne Creswick VIC 3363 Creswick VIC 3363 Phone: 0353214150 Phone: 0353214150 Fax:0353214135 Fax:0353214135 Email:[email protected] Email:[email protected] In submitting this report, the researchers have agreed to RIRDC publishing this material in its edited form. RIRDC Contact Details Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 1, AMA House 42 Macquarie Street BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4539 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.rirdc.gov.au Published in October 2003 Printed on environmentally friendly paper by Canprint - ii - Foreword Australian farmers have generally embraced tree planting on their properties for environmental benefit for some time and these benefits are, more or less, well understood and accepted. -

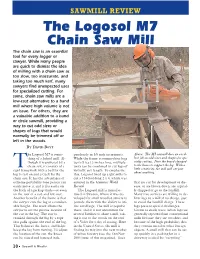

The Logosol M7 Chain Saw Mill the Chain Saw Is an Essential Tool for Every Logger Or Sawyer

SAWMILL REVIEW The Logosol M7 Chain Saw Mill The chain saw is an essential tool for every logger or sawyer. While many people are quick to dismiss the idea of milling with a chain saw as too slow, too inaccurate, and taking too much kerf, many sawyers find unexpected uses for specialized cutting. For some, chain saw mills are a low-cost alternative to a band mill where high volume is not an issue. For others, they are a valuable addition to a band or circle sawmill, providing a way to cut odd sizes or shapes of logs that would normally be trimmed off or left in the woods. By David Boyt he Logosol M7 is some- pendently in 1/8 inch increments. Above: The M7 sawmill does an excel- thing of a hybrid mill. Al- While the frame accommodates logs lent job on odd sizes and shapes for spe- though it is powered by a up to 8 feet 3 inches long, multiple cialty cutting. Note the board clamped chain saw, it consists of a units can be combined to cut logs of to the knees to support the log. With a T little creativity, the mill will cut just rigid framework with a bed for the virtually any length. To emphasize about anything. log to rest on and a track for the this, Logosol lined up eight mills to chain saw. It has the advantages of cut a 114-foot-long 2 x 4, which was extreme portability (one person can entered in the Guinness World that are cut for development or dis- easily move it, and it fits easily on Records. -

Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Edition 2 English

Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Human-Wildlife Conflicts Editor: M. Laverdière Assistant Editors: L. Bakker, A. Ndeso-Atanga FAO Regional Office for Africa [email protected] www.fao.org/world/regional/raf/workprog/forestry/magazine_en.htm FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Accra, Ghana 2007 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Communication Division, FAO,Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected]. ©FAO 2007 Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Table of Contents Page Editorial 1 News News in Africa 2 News Worldwide 3 FAO News 5 Thematic News in Africa 6 Thematic News Worldwide 6 Special Feature Human-Wildlife Conflict: A Case for Collaboration 8 Madden, F. -

Tredns Inf Forest Ownership, Forest Resources Tenure and Institutional

TRENDS IN FOREST OWNERSHIP, FOREST RESOURCE TENURE AND INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS CASE STUDY FROM GHANA 1 K. Akyeampong Boakye and K. Affum Baffoe 1 Resource Management Support Centre, Forestry Commission of Ghana i Contents SUMMARY III ACRONYMS V INTRODUCTION 1 Research objectives 1 THE FORMAL AND LEGAL CONTEXT 2 The tenure system 2 Stakeholders 3 Ownership rights and responsibilities 4 Management agreements: rights and responsibilities 6 Planning and monitoring of on- and off-reserve production 6 CHANGES AND TRENDS 8 Forest tenure policy 9 ANALYSIS OF FOREST MANAGEMENT AND TENURE SYSTEMS 10 Forest management 10 Livelihoods 10 Women and land tenure 12 Human and financial arrangements for forest resource management 12 Policy and legislation 13 ASSESSMENT OF THE DIFFERENT FOREST TENURE SYSTEMS 15 Contribution to sustainable forest management and poverty alleviation 15 Management and harvesting of trees and forests 16 Adapting planning and monitoring systems 17 CONCLUSION 18 Proposals for the way forward 18 REFERENCES 20 Annex 1. Map of Ghana 21 Annex 2. Vegetation zones and forest reserves in Ghana 22 Annex 3. Road and forest map of Ghana 23 ii Summary At the beginning of the twentieth century, the forest area of Ghana covered about 34 percent of the total land area. Forest reservation was started in 1927 by the colonial administration and ensured the reservation of 11 percent of the country’s total land area. In all, 282 forest reserves and 15 wildlife protected areas, occupying more than 38 000 km2 or about 16 percent of the total land area, were established and gazetted in Ghana. There was an additional 4 000 km2 of forest outside this gazetted area. -

Evaluating the Efficiency of Forestry Policy for Inclusive Growth in Ghana

Evaluating the Efficiency of Forestry Policy for Inclusive Growth in Ghana Jonathan D. Quartey Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. Email: [email protected] and Anthony K. Osei-Fosu Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. Email: [email protected] DOI//http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v15i2.6 Abstract The study evaluates the efficiency of forestry policy implemented in Ghana, where about 70% of the population depends on forest resources for livelihood and cultural purposes. It sought to assess how efficiently forestry policy had been implemented in Ghana, to inform policy on how benefits of forestry policy could promote inclusive growth.I t employs an inclusive wealth framework to ascertain the social opportunity cost due to forestry policy implementation in Ghana, an indicator of the economic welfare effect of the policy. The results show negative net divergence in revenue due to forestry policy implementation, indicating a distorting influence of forestry policy onG hana’s forestry sector, creating increasing inefficiency. Computed summary ratios – Nominal Protection Coefficient, Effective Protection Coefficient and Subsidy Ratio to Producers, confirmed that forestry policy implementation in Ghana had induced lower economic welfare in the country. Ghana will need to apply the holistic model, with special emphasis on the economic and social subsectors to ensure that implemented forestry policy leads to inclusive growth. Keywords: Efficiency,F orestry policy, Ghana, Inclusive growth, Policy analysis matrix Introduction Natural capital has been widely recognised as a crucial component of the total wealth of nations (Gundimeda & Atkinson, 2014). Following this recognition, one CC-BY License | 108 Ghana Journal of Development Studies, Vol. -

Forest Governance in Ghana

EU Forest Governance in Ghana An NGO perspective A report produced for FERN by Forest Watch Ghana, March 2006 Recommendations for a Voluntary Partnership Agreement with the Abbreviations AFLEG African Forest Law Enforcement Governance CBNRM Community-based Natural Resource Management CFC Community Forest Committees CFM Collaborative Forest Management CSO Civil Society Organisation DfID Department for International Development (UK) EC European Community ECFP European Community Forestry Platform EU European Union FLEGT Forest Law Enforcement Governance & Trade FSDP Forest Sector Development Project FWP Forest & Wildlife Policy (1994) GHATEX Ghana Association of Teak Exporters GTA Ghana Timber Association GTMO Ghana Timber Millers Organisation IRS Internal Revenue Service MSG Multi Stakeholders Group NTFP Non-timber Forest Product TRF Timber Rights Fees TUP Timber Utilisation Permit (non-commercial logging permit) VLTP Validation of Legal Timber Programme VPA Voluntary Partnership Agreement Author: Kyeretwe Opoku, Civic Response Ghana Photos: Dorothy Jackson Cover photo: Editor: Rebecca Whitby Local communities Design: Daan van Beek, Utrecht, Netherlands need access to Printed: Zuidam Uithof, Utrecht, Netherlands forest products and © FERN, March 2006 a sustainable, well managed forest FERN office UK resource. Skilled 1C Fosseway Business Centre, Stratford Road, Moreton in Marsh, GL56 9NQ, UK craftsmen make dugout canoes FERN office Brussels from species such 4 Avenue de l’Yser, 1040 Brussels, Belgium as wawa trees (Triplochiton www.fern.org scleroxylon), generating an This publication was made possible with support from the UK Department for income and International Development (DFID) and the Dutch Ministry of Environment (VROM). providing essential equipment for local The views expressed in this report are those of Forest Watch Ghana and have been fishermen. -

Falling Into Place

Policy thatworksforforestsandpeople4No: G Falling into place HANA Ghanaian forestry is in the process of rediscovering its past, consolidating what it does best, and G learning from innovative new forest management initiatives. Falling Into Place charts the evolution of policies that affect forests. It describes how the ‘timber-first’ orientation of forestry is giving way to more collaborative policy and forest management for a greater range of forest values, and how tactical Policy that approaches led by key opinion-formers and policy-makers have been successful at overcoming works for forests resistance to change. There are major challenges ahead: combining the economic potential of forest and people resources with maintaining environmental quality and human well-being; and rooting decision-making in places where people are really motivated to take action. Yet, after years of ‘things falling apart’, it seems that Ghanaian forestry is beginning to fall into place. “Through a careful compilation and analysis of data and case studies, Falling Into Place provides a brilliant examination of forest policy and policy processes in Ghana. Its conclusions and recommendations indicate plausible future directions for improved policy. It will be ex- tremely useful for all those interested in understanding and explaining forest policy in particu- lar, and policy in general”. E.O.Nsenkyire, Chief Conservator of Forests, Forestry Department, Ghana Policy that works for forests and people series Forest issues often concern large amounts of money, long timeframes, huge areas of land, and diverse livelihoods. The issues are complex and vary from place to place. However, a pattern of forest problems is common to many countries: continuing loss of natural forests; over-concentrated control and inequitable access to forests; an ill-informed public; and poorly-resourced, inflexible forestry hana Kotey institutions.