Tourism Mobility in the Suburbs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Det Offentlige Bygger Og Vedligeholder

Bygningskultur og Håndværk 2002 – Det offentlige bygger og vedligeholder Det offentlige har skabt mange fine bygninger og har fortsat en forpligtelse til ikke bare at bygge godt, men i lige så høj grad til at vedligeholde det byggede på den håndværksmæssige bedste måde. Med årets tema »Det offentlige bygger og vedligeholder« har Bygningskultur og Håndværk 2002 sat fokus på det særlige ansvar som stat, amter og kommuner har over for vor bygningskultur. I hæftet gives der en række eksempler på bygninger, som det offentlige har bygget gennem tiderne. Det offentlige bygger og vedligeholder Kulturarvsstyrelsen Kulturarvsstyrelsen Kulturministeriet Kulturministeriet Titel. Det offentlige bygger og vedligeholder Udgivet af: Kulturarvsstyrelsen, Kulturministeriet 2002 Foto: Ole Akhøj Niels-Holger Larsen, side 34 og 37 Redaktion: Lis Jensen, Kulturarvsstyrelsen Henriette Uggerly, Kulturarvsstyrelsen Grafisk Tilrettelæggelse: Monsoon GI Repro og tryk: Frederiksberg Bogtrykkeri a/s Papir: Novatech Matt Oplag: 15.000 eksemplarer ISBN: 87-91298-00-8 Henvendelse om Bygningskultur og Håndværk 2002 Sekretariatet Bygningskultur og Håndværk 2002 Raadvad 40 2800 Lyngby Telefon 45 56 53 01 Fax 45 50 52 07 [email protected] www.bygningskulturog haandvaerk.dk Kulturarvsstyrelsen Slotsholmsgade 1 1216 København K Telefon 72 26 51 00 Fax 72 26 51 01 [email protected] Raadvad Centeret Raadvad 40 2800 Lyngby Telefon 45 80 79 08 Fax 45 50 52 07 [email protected] B Y G N I N G S K U L T U R O G H Å N D V Æ R K 2 0 0 2 1 Det offentlige bygger og vedligeholder Bygningskultur og Håndværk 2002 2 B Y G N I N G S K U L T U R O G H Å N D V Æ R K 2 0 0 2 Indhold 5 Forord af Brian Mikkelsen, kulturminister 7 Den røde bygning af Claus M. -

Slægten Lottrup Fra 1545 (Aner På Mødrene Side) /Subject (None

Slægten Lottrup fra 1545 (Aner på mødrene side går tilbage til ca. 1450) med sidegrene til slægterne Cleemann, Heise m.fl Produceret af Jens Lottrup november 2016 Indhold Forord .......................................................................................................................... 3 Om slægten Lottrup ..................................................................................................... 5 Aner på mødrene side for Mogens Christian Hanssøn Lottrup f. 1656 ....................... 6 Efterkommere til Hans Lottrup f. 1545 ....................................................................... 15 Efterkommere til Gert Cleemann f.ca. 1695 ................................................................ 87 Efterkommere til Hans Heise f. omk. 1565 ................................................................. 98 Billeder (primært Lottrup slægten) .............................................................................. 112 Kilder ........................................................................................................................... 118 Navneindex .................................................................................................................. 119 [email protected] 2 Forord Igennem flere år var det mit ønske, at kunne få etableret et overblik over slægten Lottrup. Det første slægtsmateriale arvede jeg fra min fader Holger Lottrup Thomsen. Dette materiale gav mig mulighed for at starte min første database over familien Lottrup. I begyndelsen af 2003 fik jeg en henvendelse -

02Mølleådalen Industriens Vugge

PÅ TUR TIL MøllEÅDALEN 02 INDUStriENS VUGGE 25 FantastiskE INDUSTRIER SE MERE PÅ WWW.25FANTASTISKE.DK Mange synes, at Mølleådalen er Danmarks smukkeste naturområde. Her strømmer Mølleåen fra Furesøen gennem Nordsjællands landskab og ud til Øresund ved den gamle Strandmølle. Ikke alle ved dog, at dette område er Danmarks ældste industrilandskab. Siden middelalderen har der langs den brusende å ligget den ene mølle efter den anden som med tiden udviklede sig til store og små fabriks- anlæg. Der er både vandre- og cykelstier, som man kan følge langs hele Mølleåen. FOLD HER 02 // MØLLEÅDALEN - INDUSTRIENS VUGGE ØRESUND 09 07 08 RÅDVAD 05 06 VIRUM 04 BREDE FURESØEN 03 01 02 KGS. LYNGBY BAGSVÆRD SØ FOLD HER 01 FREDEriKSDAL 04 BREDE VÆRK Mølleåens vandkraft var den oprindelige grund til, at klæde- I 1649 byggede kgl. rentemester Henrik Müller et kobberværk I Brede var der krudtværk 1628-68, kobberværk 1668-1855 fabrikken blev placeret her. Selvom man hurtigt investerede i med tilhørende arbejderboliger, bryggeri og kro, som supple- og klædefabrik 1831-1956. Bortset fra hovedbygningen fra en dampmaskine blev Mølleåens vand stadig udnyttet til vask, ment til den middelalderlige mølle. Men anlægget gik til under 1795 og en vagtbygning er de eksisterende bygninger fra valkning og farvning. Svenske Krigene få år senere. I dag kan man se opdæmningen klædefabrikkens tid. og resterne af en møllebygning opført efter en brand i 1851. Brede Værk udgjorde et patriakalsk mini-samfund, hvor der blev Hovedparten af bygningen blev dog revet ned i forbindelse med I Brede Værk kan man se, hvordan industriens produktionsbyg- taget hånd om arbejderne ’fra vugge til grav’. -

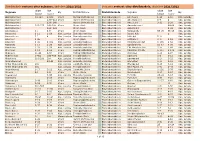

Skoledistrikter 2021-2022

Distriktsskole sorteret efter vejnavne, skoleåret 2021/2022 Vejnavne sorteret efter distriktsskole, skoleåret 2021/2022 ulige lige ulige lige Vejnavn By Distriktsskole Distriktsskole Vejnavn By husnr husnr husnr husnr Abildgaardsvej 33-123 2-108 Virum Hummeltofteskolen Engelsborgskolen Agerbovej 1-11 2-16 Kgs. Lyngby Abildgaardsvej 130+132 Virum Hummeltofteskolen Engelsborgskolen Agermånevej 1-7 4 Kgs. Lyngby Abildgaardsvej 138+140 Hummeltofteskolen Engelsborgskolen Agnetevej 3-33 2-28 Kgs. Lyngby Abildgaardsvej 125-175 142-180 Virum Virum Skole Engelsborgskolen Amundsensvej 64-66 Kgs. Lyngby Abildgaardsvej 134+136 Virum Skole Engelsborgskolen Asavænget 4-36 Kgs. Lyngby Agerbakken 3-9 4-6 Virum Virum Skole Engelsborgskolen Bagsværdvej 65-95 66-96 Kgs. Lyngby Agerbovej 1-11 2-16 Kgs. Lyngby Engelsborgskolen Engelsborgskolen Baune Alle 2 Kgs. Lyngby Agermånevej 1-7 4 Kgs. Lyngby Engelsborgskolen Engelsborgskolen Birkedal 5-23 Kgs. Lyngby Agernvej 1-45 Virum Virum Skole Engelsborgskolen Birkhøjvej 3-17 4-16 Kgs. Lyngby Agervang 1-35 4-102 Kgs. Lyngby Lindegårdsskolen Engelsborgskolen Blomstervænget 1-105 2-52 Kgs. Lyngby Agnesvej 3-17 2-26 Kgs. Lyngby Lindegårdsskolen Engelsborgskolen Buddingevej 15-87 6-90 Kgs. Lyngby Agnetevej 3-33 2-28 Kgs. Lyngby Engelsborgskolen Engelsborgskolen Chr.Winthers Vej 3-55 2-48 Kgs. Lyngby Ahornvej 3-19 4-16 Virum Fuglsanggårdsskolen Engelsborgskolen Christian X's Alle 5-117 2-172 Kgs. Lyngby Akacievej 11-49 4-50 Virum Fuglsanggårdsskolen Engelsborgskolen Durosvej 1-15 2-20 Kgs. Lyngby Akademivej 1-451 100-450 Kgs. Lyngby Trongårdsskolen Engelsborgskolen Egebovej 1-9 2-12 Kgs. Lyngby Akustikvej 353-355 354 Kgs. Lyngby Trongårdsskolen Engelsborgskolen Egevænget 1-17 2-22 Kgs. -

Project and Partners in Brief

SUSCOD Project and partners in brief European Union European Regional Development Fund In this folder you will find a brief overview of the SUSCOD project. Each of the partners presents itself and their activities within the project. If you are interested in following SUSCOD please visit our website: www.SUSCOD.eu Get connected About SUSCOD Gertjan Nederbragt, project manager: Kim Uittenbosch: [email protected] [email protected] SUSCOD aims to make a step change in the application of integrated coastal zone management (ICZM). In doing so coastal potentials can be utilised to full advantage and broader support for coastal management measures can be secured. The North Sea Region coastal area is an area with high value SUSCOD brings together partners who want to realise this assets, where the pressure for competing user functions is through a well coordinated transnational team approach. being strongly felt. It faces the anticipated impacts of climate They all have eroding coasts. They share the urgent need change. Precautionary measures are required to guarantee to act proactively because of safety reasons and also the safety for inhabitants and safeguard its values. The challenge ambition to find practical solutions. Leading forces can be is to find positive solutions that also ensure fully integrated characterised as the wish for sustainable solutions and the social, economic and environmental development. improvement of spatial quality. 3 | SUSCOD Project and partners in brief Project objectives Central in SUSCOD is the development of a practical tool: the ICZM-assistant, its introduction to potential users and 1 Exchange knowledge and expertise its demonstrated value at test locations. -

Dyrehavens Maleres Udstilling

& '"HK/ $ 592. ^ T FORENINGEN DYREHAVENS MALERES UDSTILLING 1.9*2*0 OKTOBER 1920 » d. 17.—31. incl. &3S£>5 £ ^LEf& DEN FRIE UDSTILLING OKTOBER 1920 * STATENS ^ kunst::.",tokiske FUTo GU Al t . SAMLir. <; FORENINGENS POSTADRESSE: STENGAARDS ALLÉ 7 HELLERUP TELEFON: HELLERUP 1350 Julius Heckscher - • Assuranceforretning • • Grundlagt 1852 W Al 1 e Arter Assurance Østergade31 - København K. - - Telefoner: 1527 - 10.526 - 10.527 - - Udstillernes Adresser findes anført bag i Kataloget. ARBEJDER MED MOTIVER FRA DYREHAVEN OG OMEGN Willi- Andersen: Nr. Kr. 1. Vej til Fuglesangsøen 600 Chr. Asmussen: 2. De tre Popler, Vilvordevej 600 3. Brune Bøge, Charlottenlund 250 4. Ved Løvfaldstid i Krattet 450 5. Foraar 150 6. Ved Bernstorff Avlsgaard 350 7. Udhus ved Hovmarksgaarden 200 8. Birkerenden, Bernstorff 450 Tare Aubertin-Jespersen: 9. Formiddag paa Sletten 200 10. Solopgang 100 Au g. Den c ker: 11. Tidligt Foraar i Ermelunden 550 12. Birketræer i et Indelukke i Nærheden af Fug lesangsøen, Marts 800 13. Vejen forbi Bakken, Februar 500 14. Trægruppe i Nærheden af Schimmelmanns Vildthus, Septemberaften 1600 - 3 - Kr. 15. Elletræer i Formiddagssol ved Schimmelmanns Vildthus 700 16. Aften i August, ved Schimmelmanns Vildthus 650 17. Eftermiddag i September, ved Schimmelmanns Vildthus 700 Hans Flygenring: 18. Ved Dyrehavsbakken, Marts 500 19. Ved Dyrehavsbakken, Marts 500 H. Gyde-Petersen, R. af Dbg.; 20. Kildesøen, Dyrehaven 800 21. Decemberdag, Dyrehaven (Privat Eje) Thorvald Hansen: 22. Kronvildt paa Erimitagesletten 550 23. Køer i Indelukket ved Fortunen 400 24. Køer ved et Vandtrug, Eftermiddag 450 25. Køer i Indelukket ved Fortunen 550 26. Kronvildt, September 200 27. Efteraar i Dyrehaven 200 Alfred Harlig: 28. -

Find Your Way Around Lyngby

Find your way around Lyngby Find your way and use your smartphone to learn about the town’s history What is ”Find your way around Denmark”? ”Find your way around Denmark” is a simpli- fied version of orienteering. You can walk or run from marker to marker. Most ”Find your way around ..” are in woods and parks. Some ”Find your way around ..” are in towns and take you to places with interesting stories. See more at www.findveji.dk Find your way around Lyngby ”Find your way around Lyngby” is a dif- ferent way of learning about Lyngby’s cultural heritage. The tour takes you around the historical town of Lyngby on a treasure hunt where the prizes are healthy exercise and tales from when Lyngby was a royal residence and later a hub for Denmark’s jet set. You can get more information at www. stadsarkivet.ltk.dk If you would like to find other trips simi- lar to the one around Lyngby, then look at www.findveji.dk The map can also be downloaded and printed from Lyngby Orienteering Club (www.lyngbyok.dk). R A L W T U T H F E N U I B O E T E A H How to… The tour consists of 20 locations. The locations are shown on the map with a purple circle, and the place to find is in the middle of the circle. There is a picture of each location in this folder. Once you have found the picture at your location, write the letter on the picture in the table at the bottom of the map. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Daňo Juraj - (2007) do výtvarného života vstúpil tesne po 2. svetovej vojne; v tvorbe prekonal niekoľko vývojových zmien, od kompozícií dôsledne a detailne interpretujúcich farebné a tvarové bohatstvo krajiny, cez krajinu s miernou farebnou, tvarovou i rukopisnou expresionistickou nadsádzkou, až ku kompozíciám redukujúcim tvary na ich geometrickú podstatu; tak v krajinárskych, ako aj vo figurálnych kompozíciách, vyskytujúcich sa v celku jeho tvorby len sporadicky, farebne dominuje modro – fialovo – zelený akord; po prekonaní experimentálneho obdobia, v ktorom dospel k výrazne abstrahovanej forme na hranici informačného prejavu, sa upriamoval na kompozície, v ktorých sa kombináciou techník usiloval o podanie spoločensky závažnej problematiky; vytvoril aj celý rad monumentálno-dekoratívnych kompozícií; od roku 1952 bol členom východoslovenského kultúrneho spolku Svojina, zároveň členom skupiny Roveň; v roku 1961 sa stal členom Zväzu slovenských výtvarných umelcov; od roku 1969 pôsobil ako umelec v slobodnom povolaní; v roku 1984 mu bol udelený titul zaslúžilého umelca J. Daňo: Horúca jeseň J. Daňo: Za Bardejovom Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 1 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo J. Daňo: Drevenica Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 2 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo: J. Daňo Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 3 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo: Ulička so sypancom J. Daňo: Krajina Daňový peniaz - Zaplatenie dane cisárovi dánska loď - herring-buss Dánsko - dánski ilustrátori detských kníh - pozri L. Moe https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Danish_children%27s_book_illustrators M Christel Marotta Louis Moe O Ib Spang Olsen dánski krajinári - Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 4 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Danish_landscape_painters dánski maliari - pozri C. -

Download the Publication Arne Jacobsen's Own House

BIBLIOGRAPHY Henrik Iversen, ‘Den tykke og os’, Arkitekten 5 (2002), pp. 2-5. ARNE JACOBSEN Arne Jacobsen, ‘Søholm, rækkehusbebyggelse’, Arkitektens månedshæfte 12 (1951), pp. 181-90. Arne Jacobsen’s Architect and Designer The Danish Cultural Heritage Agency, Gentofte. Atlas over bygninger og bymiljøer. Professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen (1956-1965). Copenhagen: The Danish Cultural Heritage Agency, 2004. He was born on 11 February 1902 in Copenhagen. Ernst Mentze, ‘Hundredtusinder har set og talt om dette hus’, Berlingske Tidende 10 October 1951. His father, Johan Jacobsen was a wholesaler. Félix Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Arne Jacobsen. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1989. Own House His mother, Pouline Jacobsen worked in a bank. Carsten Thau og Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen. Copenhagen: Arkitektens Forlag, 1998. He graduated from Copenhagen Technical School in 1924. www.arne-jacobsen.com Attended the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture in www.realdania.dk Copenhagen (1924-1927) Original drawings from the Danish National Art Library, The Collection of Architectural Drawings Strandvejen 413 He worked at the Copenhagen City Architect’s office (1927-1929) From 1930 until his death in 1971, he ran his own practice. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Peter Thule Kristensen, DPhil, PhD is an architect and a professor at the Institute of Architecture and JACK OF ALL TRADES Design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation (KADK), where he is in charge of the post-graduate Spatial Design programme. He is also a core A total one of a kind, Arne Jacobsen was world famous. -

Gift På Prominent Byggeri Vanedannende Efteruddannelse Godt Nytår

NR. 6 DECEMBER 2019 BRANCHEBLAD FOR MURERE Gift på Vanedannende Godt prominent byggeri efteruddannelse nytår SIDE 11 SIDE 14 SIDE 14 3F Bygge-, Jord- og Miljø · Mølle Allé 26 · 2500 Valby · www.3f.dk/bjmf LEDER Medlemsblad for 3F Bygge-, Jord- og Miljø- arbejdernes Fagforening Tak for i år! Mølle Allé 26 2500 Valby Tlf.: 70 30 08 26 AF CLAUS WESTERGREEN, FORMAND FOR BJMF [email protected] www.3f.dk/bjmf Et hektisk år er næsten gået, og et Hvad vi herhjemme kan og på kammeratlig vis at dyste på nyt og sikkert lige så hektisk ven- skal gøre, er fortsat at kæmpe forskellig vis og samtidig være Tilrettelæggelse ter på den anden side af nytåret. for bedre løn- og arbejdsforhold! forenet på kryds og tværs. Det er og produktion Så lad os huske lidt på det opnåede Vi nærmer os OK20 med hastige BJMFs forskellige faglige klubber Lotte Ott (DJ) i årets løb. skridt og mange arbejdspladser der arrangerer og stiller aktivister [email protected] BJMF har ført en bunke sager og klubber er allerede på banen på dagen og dét er også en indsats Tlf.: 20 98 37 27 sammen med – og for- medlem- med løftet om at vi står sammen der fortjener et skulderklap. merne. Metroen er næsten færdig- i OK20. Herligt at se! 3F kongressen har også fyldt Kontakt bygget på godt og ondt, og vi kan Tid til andre typer aktiviteter i årets løb. Vi har brugt mange [email protected] drage en masse erfaringer, der vil har der også været. Årets udgave kræfter og timer både før, under komme os og arbejdere på fremti- af Fagenes Fest var endnu engang og efter kongressen, men sådan Ansvarshavende dige store anlægsbyggerier til gode. -

A Digital Standard Towards a Digital Bureaucracy

01/2019 cView A digital standard Towards a digital bureaucracy In this issue Public authorities on the way to a digital bureaucracy Rethink your approach – software alone won’t cut it From paper to mission critical systems using standard software Digital bureaucracy Towards a digital bureaucracy Public authorities’ work procedures are alike. That’s called bureaucracy. It is commonly known that public autho- The public sector itself, then, dictates a became clear that even though bureaucracy rities regard themselves as being different market development which leaves providers prevails, the transition from paper-based to each other. That’s why they choose with no incentive to create sector-wide solu- to digital bureaucracy has far reaching individual IT systems. However, this entails tions. Additionally, there is no competition consequences. great costs and operational challenges as between public authorities. developing large, new IT systems often go cBrain’s model, method and F2 software awry – both in the public and the private The competition between private compani- encourage the conversion of analogue sector. Additionally, maintenance and es creates fertile soil for innovation and new bureaucracy to a digital bureaucracy, further development of individual solutions products, including better and cheaper stan- which has proven a successful approach often mean significant costs and risks. dard systems which provide the customers to digitisation. It is also a demanding with competitive advantages and which can approach, however: it requires mainly that The private sector has taken the consquen- be used across the sector. management is involved, but the organi- ce of this a long time ago. IT providers sation is also required to have an overview have specialized and offer a great number cBrain’s standard system F2 challenges the of its business processes.