Comparison of Traditional and Manufactured Cold Weather Ensembles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taltheilei Houses, Lithics, and Mobility

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-09-06 Taltheilei houses, lithics, and mobility Pickering, Sean Joseph Pickering, S. J. (2012). Taltheilei houses, lithics, and mobility (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27975 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/177 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Taltheilei Houses, Lithics, and Mobility by Sean J. Pickering A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2012 © Sean J. Pickering 2012 Abstract The precontact subsistence-settlement strategy of Taltheilei tradition groups has been interpreted by past researchers as representing a high residential mobility forager system characterized by ephemeral warm season use of the Barrenlands environment, while hunting barrenground caribou. However, the excavation of four semi-subterranean house pits at the Ikirahak site (JjKs-7), in the Southern Kivalliq District of Nunavut, has challenged these assumptions. An analysis of the domestic architecture, as well as the morphological and spatial attributes of the excavated lithic artifacts, has shown that some Taltheilei groups inhabited the Barrenlands environment during the cold season for extended periods of time likely subsisting on stored resources. -

Kalemie L'oubliee Kalemie the Forgotten Mwiba Lodge, Le Safari Version Luxe Mexico Insolite Not a Stranger in a Familiar La

JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N° 20 TRIMESTRIEL N° 20 5 YEARS ANNIVERSARY 5 ANS DÉJÀ LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE TRAVEL in AFRICA LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE HAMAJI MAGAZINE MEXICO INSOLITE Secret Mexico GRAND ANGLE MWIBA LODGE, LE SAFARI VERSION LUXE Mwiba Lodge, luxury safari at its most sumptuous VOYAGE NOT A STRANGER KALEMIE L’OUBLIEE IN A FAMILIAR LAND KALEMIE THE FORGOTTEN Par Sarah Waiswa Sur une plage du Tanganyika, l’ancienne Albertville — On the beach of Tanganyika, the old Albertville 1 | HAMAJI JUILLET N°20AOÛT SEPTEMBRE 2018 EDITOR’S NEWS 6 EDITO 7 CONTRIBUTEURS 8 CONTRIBUTORS OUR WORLD 12 ICONIC SPOT BY THE TRUST MERCHANT BANK OUT OF AFRICA 14 MWIBA LODGE : LE SAFARI DE LUXE À SON SUMMUM LUXURY SAFARI AT ITS MOST SUMPTUOUS ZOOM ECO ÉCONOMIE / ECONOMY TAUX D’INTÉRÊTS / INTEREST RATES AFRICA RDC 24 Taux d’intérêt moyen des prêts — Average loan interest rates, % KALEMIE L'OUBLIÉE — THE FORGOTTEN Taux d’intérêt moyen des dépôts d’épargne — Average interest TANZANIE - 428,8 30 % rates on saving deposits, % TANZANIA AT A GLANCE BALANCE DU COMPTE COURANT EN MILLION US$ 20 % CURRENT ACCOUNT AFRICA 34 A CHAQUE NUMERO HAMAJI MAGAZINE VOUS PROPOSE UN COUP D’OEIL BALANCE, MILLION US$ SUR L’ECONOMIE D’UN PAYS EN AFRIQUE — IN EVERY ISSUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE OFFERS 250 YOU A GLANCE AT AN AFRICAN COUNTRY’S ECONOMY 10 % TRENDY ACCRA, LA CAPITALE DU GHANA 0 SOURCE SOCIAL ECONOMICS OF TANZANIE 2016 -250 -500 0 DENSITÉ DE POPULATION PAR RÉGION / POPULATION DENSITY PER REGION 1996 -

The Cloth Parka

CCM-00072 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS The Cloth Parka Introduction face can stand some exposure if forehead and cheeks are protected Making cloth parkas is fun if one has done some with a ruff of long, shaggy fur sewing before and if simple designs are used. The around the face. A scarf over the cloth parka is a traditional item of clothing for mouth is not good, as it soon Alaska Natives and is popular with non-Native becomes frosted and icy. people living in Alaska as well. It is a practical way of staying warm and combines both Native and Roomy. A loose parka Western design techniques. The parka always has permits easy circulation of a hood, and a zipper is used for the front closing, blood, saves heat and wears although some sort of additional fastening should better. A good parka has be included for anyone who might have trouble with large armholes and is loose a zipper when the weather is extremely cold. Loop across the shoulders but is buttonholes or frogs could be used with buttons. belted and snug at the hips. To avoid wasting expensive materials one should Mittens should be loose enough take time to make a test pattern. Only experienced to double your fist. seamstresses should make the parka without a test shell. Boots or mukluks should be large enough for extra socks and inner The beginner should use easy-to-sew materials and soles and loose enough to wiggle simple trimmings. A very effective parka can be your toes. -

Confidential the District Solicitied 401 Suppliers and Received 9 Responses

BID TABULATION GARLAND INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT Auction Title:168-20 Bid Rfq Softball Uniforms & Num:32339 Equipment *Confidential Ln # Award (Y/N) Reason Item Description Quantity UOM Supplier Price Extended Price 1 NA Dudley Thunder Heat Yellow Softballs 40 DZ SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC NB NB with Red stitching & NFHS STAMP #WT12YFP, core .47 – 12”, no subs district game ball Y PYRAMID SCHOOL PRODUCTS 62.00 2,480.00 AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 64.00 2,560.00 VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO 69.91 2,796.40 INC DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS 72.00 2,880.00 LTD *PRO PLAYER SUPPLY 83.97 3,358.80 2 NA Charcoal Badger Hooded Sweatshirt 15 ST SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC NB NB #1254 with two color lettering & pant #1277 open bottom no lettering, lettering & sizes to follow when order is placed, no subs fill-ins Y AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 34.00 510.00 RIDDELL ALL AMERICAN 34.45 516.75 DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS 38.57 578.55 LTD VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO 44.00 660.00 INC ROBIN BAUGH 45.00 675.00 *PRO PLAYER SUPPLY 46.95 704.25 3 NA Badger Hooded Sweatshirt #125400 & 10 ST SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC NB NB pant #147800 with two color lettering on sweatshirt & right leg of pant, sizes to follow when order is placed, no subs fill- ins Y AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 42.50 425.00 DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS 52.56 525.60 LTD ROBIN BAUGH 53.00 530.00 *PRO PLAYER SUPPLY 53.96 539.60 VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO 56.00 560.00 INC 4 NA Royal Blue Badger Hooded Sweatshirt 22 ST SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC NB NB #125400 & pant #147800 with "Colonel" "Softball" & "SG" "Softball" on pant in white, sizes to follow when -

The Developing Years 1932-1970

National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNIFORMS The Developing Years 1932-1970 Number 5 By R. Bryce Workman 1998 A Publication of the National Park Service History Collection Office of Library, Archives and Graphics Research Harpers Ferry Center Harpers Ferry, WV TABLE OF CONTENTS nps-uniforms/5/index.htm Last Updated: 01-Apr-2016 http://npshistory.com/publications/nps-uniforms/5/index.htm[8/30/18, 3:05:33 PM] National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 (Introduction) National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 INTRODUCTION The first few decades after the founding of America's system of national parks were spent by the men working in those parks first in search of an identity, then after the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 in ironing out the wrinkles in their new uniform regulations, as well as those of the new bureau. The process of fine tuning the uniform regulations to accommodate the various functions of the park ranger began in the 1930s. Until then there was only one uniform and the main focus seemed to be in trying to differentiate between the officers and the lowly rangers. The former were authorized to have their uniforms made of finer material (Elastique versus heavy wool for the ranger), and extraneous decorations of all kinds were hung on the coat to distinguish one from the other. The ranger's uniform was used for all functions where recognition was desirable: dress; patrol (when the possibility of contact with the public existed), and various other duties, such as firefighting. -

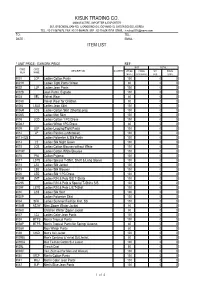

Kisuk Trading Co

KISUK TRADING CO. MANUFACTRE, IMPORTER & EXPORTER 267, GYEONDALSAN-RO, ILSANDONG-GU, GOYANG-SI, GYEONGGI-DO, KOREA TEL : 82-31-9674676, FAX :82-31-9684678, M.P : 82-10-62437758 EMAIL : [email protected] TO : TEL : DATE : EMAIL : ITEM LIST * UNIT PRICE : EXWORK PRICE REF: UNIT TOTAL CODE CODE DESCRIPTION QUANTITY WT(KG PRICE WT PRICE NUM NAME /BALE) (USD/BALE) (KG) (USD) #001 LCP Ladies Cotton Pants 100 0 0 #001H Ladies Tight Pants Winter 80 0 0 #002 LJP Ladies Jean Pants 100 0 0 #002B Jean Pants, B grade 100 0 0 #003 VEL Velvet Wear 80 0 0 #003C Velvet Wear for Children 80 0 0 #006J LBJS Ladies Jean Skirt 100 0 0 #006M LCS Ladies Cotton Skirt (Short&Long) 100 0 0 #006S Ladies Mini Skirt 100 0 0 #008 LCD Ladies Cotton 1 PC Dress 100 0 0 #008-1 Ladies Winter 1PC Dress 80 0 0 #009 LEP Ladies Legging/Tight Pants 100 0 0 #012 LP Ladies Panties (underwear) 100 0 0 #013+028 Ladies Polyester & Silk Pants 100 0 0 #014 LS Ladies Silk Night Gown 100 0 0 #015 LCB Ladies Cotton Blouses without White 100 0 0 #015W Ladies Cotton White Blouses 100 0 0 #016 PAJ Cotton Pyjama 100 0 0 #017 LSTS Ladies Special T-Shirt, Short & Long Sleeve 100 0 0 #018 LSJ Ladies Silk Jacket 100 0 0 #019 LSB Ladies Silk Blouses 100 0 0 #020 LSD Ladies Silk 1 PC Dress 100 0 0 #029M LMT Ladies R/N & Polo S/S T-Shirts 100 0 0 #029S Ladies R/N & Polo & Special T-Shirts S/S 100 0 0 #029F LSTS Ladies R/N & Polo L/S T-Shirt 100 0 0 #030 LSS Ladies Silk Skirt 100 0 0 #030P Ladies Polyester Skirt 100 0 0 #034 SFK Ladies Summer Fashion Knit, SS 100 0 0 #036M AZJW Men Zipper Winter -

Uniform Newsgram 2019 Winter

A Newsletter keeping you up to date on uniform policy and changes Winter 2019-20 Summer 2019 UNIFORM NEWSGRAM Winter Uniform Wear and News In this issue: NAVADMIN 282/19 - NAVADMIN 282/19 NAVADMIN 282/19 Navy Uniform Policy and Uniform Initiative - Gold Star/Next of Kin Lapel Button Update has been released and provides updates on recent Navy uniform - Black Neck Gaiter Optional Wear policy initiatives. - Optional PRT Swimwear - Acoustic Technician CWO Insignia Gold Star Lapel Button (GSLB)/Next of Kin Lapel - Uniform Initiatives Button (NKLB) Optional Wear - NWU Type III: Know Your Uniform The GSLB and NKLB designated for eligible survivors of - Frequently Asked Questions Service Members who lost their lives under designated circumstances are now - ‘Tis the Season: Authorized Outerwear authorized for optional wear with Service Dress and Full Dress uniforms. - Myth Busted: Navy-issued Safety Boots - NWU Type III Fit Guide Black Neck Gaiter Optional Wear - New Uniform Mandatory Wear Dates NAVADMIN 282/19 authorized the optional wear of a Black Neck Gaiter during extreme cold weather conditions as promulgated by Regional Commanders ashore and as prescribed by commanding officers afloat. When authorized, it may be worn with the following cold weather outer garments only: Cold Weather Parka, NWU Type II/III Parka, Peacoat, Reefer, and All Weather Coat. Optional Physical Readiness Test (PRT) Swimwear Optional wear of full body swimwear is authorized for Sailors who elect to swim during their semi-annual PRT. Optional swimwear will be navy blue or black in color, conservative in design and appearance and must not prohibit the swimmer from swimming freely. -

Embellishments of the Alaska Native Gut Parka

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2008 Embellishments of the Alaska Native Gut Parka Fran Reed [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Reed, Fran, "Embellishments of the Alaska Native Gut Parka" (2008). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 127. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Embellishments of the Alaska Native Gut Parka Fran Reed (1943 - 2008) [email protected] Dealing with the various and extreme weather conditions in Alaska is a serious matter. Coastal Native Alaskans have been surviving in these severe environments for millennia. Without a local general store in which to buy a nice rain slicker, one must be resourceful with what is available. Between the hot summers and frigid winters are the transition seasons when it rains. Bird skins and fish skins were used extensively to make raincoats but it is the gut skin parka that proved so universal along the coast of Alaska (Fig. 1). From village to village different preparations, stitching methods and artistic styles are apparent and expressed in the embellishments that define the region, the culture and the function of these beautiful outer garments. For hundreds of years the indigenous people of the circumpolar region survived extreme conditions on their ingenuity and creativity. -

NIB Military Brochure

Equipping the Warfighter National Industries for the Blind 1310 Braddock Place EQUIPPING THE Alexandria, VA 22314-1691 WARFIGHTER • Ballistic NAPE Pad • Moisture Wicking T-Shirt • Helmet Cover • Frame Shoulder Connect with NIB • Helmet Pads Straps • Retention System NIB.org [email protected] • Army Combat 1-877-438-5963 Shirt • Rigger Belt • Ammunition • Poncho Liner Pouches • Entrenching Tool • Entrenching Tool Cover • MOLLE Components • Canteen and Canteen Cup • Hydration System SKILCRAFT® is a registered trademark owned and licensed by National Industries for the Blind. Delivering Quality and Value Textiles and Apparel • Flight deck jerseys • Cold Weather Items • Rigger belt - Extreme Cold Weather Clothing • Joint Service Lightweight Integrated System (ECWCS) Layer 2 under- Suit Technology (JSLIST) carrying bag garment and Layer 4 jacket • Flyer’s kit bag and gloves Our value proposition to military customers - Extreme and Intermediate Cold • Submarine laundry bag Weather Outer Layer Parka and • Highly trained and qualified workforce Trousers (EWOL/IWOL) • Cleaning swabs and slings for small arms • Enhanced continuity and continuous process improvement • Physical Fitness Apparel Plastic Injection, Blow Molding through low turnover Our Mission is to - Army and Air Force Physical Fitness and Thermoform • Tailored solutions available when and where needed Uniforms • Hydration systems • Extensive knowledge founded on decades-long partnerships Support Yours - Coast Guard t-shirts and trunks • Award binders • Reduced administrative and contracting burden allows military - Navy running pants • Plastic flatware and utensils customers to focus on mission-essential activities Since 1938, NIB has proudly delivered products, services • Army MOLLE System Components • Canteens and custom solutions to U.S. military combat forces and Cases Capabilities • Five-gallon water cans and support activities. -

Spring Lookbook

SPRING LOOKBOOK LIVE YOUR STYLE NEO SPRINGADIDAS.COM/NEO LOOKBOOK | 1 FUN IS A LIFESTYLE CHOICE NEO BRINGS FRESH LOOKS TO THE PARTY, THE CLASSROOM, AND EVERYWHERE BETWEEN NEW ANGLES ON PROVEN SILHOUETTES UNEXPECTED COLORS INSPIRED MATERIAL CHOICES ALL EXECUTED WITH FINESSE AND DESIGNED TO BE TAKEN FOR GRANTED BY FUN¯LOVING YOUTH IN THE PRIME OF LIFE THE FUTURE IS BRIGHT IN NEO 2 | ADIDAS.COM/NEO NEO SPRING LOOKBOOK | 3 STEP INTO SPRING 4 | ADIDAS.COM/NEO NEO SPRING LOOKBOOK | 5 A. C. B. D. A. POLKA DOT SWEATSHIRT C. PULLOVER A mix of polka dots and stripes gives the Polka Dot A top that goes with almost anything. This girls’ Sweatshirt a playful look. This feminine sweatshirt sweater slips on in a lightweight and flowy two- has an easy relaxed fit with a wide neckline and a tone waffle-knit fabric. metal NEO badge, in super-soft peached French GLOW CORAL ALUMINUM: M60862 / €XX.XX terry fabric. MEDIUM GREY HEATHER / WHITE: D. F78968 / €XX.XX KNIT PULLOVER With polka dots on the body and stripes on the arms, the Knit Pullover brings a special look to every day. B. SWEATER In 100% cotton fully-fashioned knit, it features a This sweater is blushing. Delicate dots add a feminine wide neckline and a relaxed fit, with metal feminine feel to this girls’ pullover. NEO branding. WHITE: M60847 / €XX.XX BLACK / WHITE: F78967 / €XX.XX 6 | ADIDAS.COM/NEO NEO SPRING LOOKBOOK | 7 A. B. C. D. E. F. B. BONES TEE Eyepatch not included. This girls’ t-shirt gets a little edgy with a crossbones graphic. -

The Noice Collection of Copper Inuit Material Culture

572.05 FA N.S. no. 22-27 199^-96 Anthropology " SERIES, NO. 22 The Noice Collection of Copper Inuit Material Culture James VV. VanStone ibruary 28, 1994 iblication 1455 • i ^l^BT TSHED BY FIELD W '^1^^ - '^ ^ ^^ ^-' '^^' '^^ "^ tt^^tor v if-li/:';^iMUiiiT;^iS.;0.!ifiiliti«)l^i?iM8iiiiiI^^ Information for Contributors to Field iana led as space permits. - ., or fractioi, i.-^i.^;;. — f, i jirinied page ia,..,v.u ; expedited processing, which reduces the publication time. Contributio; i " ' ' "ill be considc^' ^tblication regardless of ability to pay page charges, i ited authoi: itcd manuscripts, 'Ilirec complete copies of the to ' dvc .(iiu c ; abmitted (one original copy plus two review copi nachine-cc t publication or submitted to reviewers before ' ; ind.s {){ the Micntilic • , i;kl be submitted to Sr : ield Museum of Natur.' >u6U5-2496, US." Text: Manti,..- . ....j.. _,.,.;. ..s. ..;„,_„:- v, ..^ ..,....;._ .,..g,ht, Wi- by 11-inch ^.^j^. on all sides. four If typed on an IBM-compatible computer using MS-DOS, also submit text on N^ni.;\t..,- r^,\..i.,," ••;•- -> ^ '• " - ' WordPerfect 4.1, 4.2, or 5 (' ^, \i/--^. J>r\ ^-.-m.nn. V^-r-r-'c'-- WordStar programs or ASc I. - over ' 100 auinurs arc lo i > nipcrs maiui>>Lripi pci^cs, rccjucsicd suomu a ante ot Contents, a l i-; >i ! of Tables" immediately following title page. In most cases, the text should be preceded by an 'Ai ! Lonclude with "Acknowledgments" (if any) and "Literature Cited." Ml measurements should be in the metric system (periods are not used after abbreviated measu md style of headings should follow that of recent issues of Fieldiana. -

Caribou and Iglulik Inuit Kayaks

ARCTIC VOL. 47, NO. 2 (JUNE 1994) P. 193-195 Caribou and Iglulik Inuit Kayaks A century ago the Tyrrell brothers descended the Kuu the capsize victim exits his kayak and is towed hanging on (“The River” in Inuktitut, or Thelon River). As they neared around the base of the upturned stern horn of the rescue Qamani’tuaq (“The Big Broad,” or Baker Lake), elegant kayak. The overturned craft is retrieved by righting it and slender kayaks appeared and easily outpaced their voyageur-towing it with the stem horn tucked underarm. one The horns driven canoes. Evidence of kayaks in the form of broken also help secure the cross poles tied on at their bases when willow ribs discarded during bending hadalready been seen forming a catamaran. With the poles spaced well apart, well inland on Avaaliqquq (“Far Off,” orDubawnt River). normal synchronized paddling can be done. A couple of The Tyrrells were in the country of the Caribou Eskimos spoon-shaped red ornaments might be hung from the bow (so labelled by the Danish Fifth Thule Expedition, of horn tip to swing there gaily as kuviahunnihautik (“for the 1921-24), who actually comprised several distinct named joy”). After all, to kayak swiftly is elating - a high point groups. The two northern ones who lived largely inland by in the arctic summer. the later 19th centuryare called Ha’vaqtuurmiut (“Whirlpools The characteristic end horn configuration is useful, too, Aplenty People”) and Qairnirmiut (”BedrockPeople”). Their as an indicatorof possible historical connections. The jogged- kayaks were especially sleek and well made, with striking up stem is foundon prehistoric models carved of thickbark long, thin horns at theends.