Final Final Reginald M.J. Oduor Justifying Non-Violent Civil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wahu Kaara of Kenya

THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS: The Life and Work of Wahu Kaara of Kenya By Alison Morse, Peace Writer Edited by Kaitlin Barker Davis 2011 Women PeaceMakers Program Made possible by the Fred J. Hansen Foundation *This material is copyrighted by the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice. For permission to cite, contact [email protected], with “Women PeaceMakers – Narrative Permissions” in the subject line. THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS WAHU – KENYA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. A Note to the Reader ……………………………………………………….. 3 II. About the Women PeaceMakers Program ………………………………… 3 III. Biography of a Woman PeaceMaker – Wahu Kaara ….…………………… 4 IV. Conflict History – Kenya …………………………………………………… 5 V. Map – Kenya …………………………………………………………………. 10 VI. Integrated Timeline – Political Developments and Personal History ……….. 11 VII. Narrative Stories of the Life and Work of Wahu Kaara a. The Path………………………………………………………………….. 18 b. Squatters …………………………………………………………………. 20 c. The Dignity of the Family ………………………………………………... 23 d. Namesake ………………………………………………………………… 25 e. Political Awakening……………………………………………..………… 27 f. Exile ……………………………………………………………………… 32 g. The Transfer ……………………………………………………………… 39 h. Freedom Corner ………………………………………………………….. 49 i. Reaffirmation …………………….………………………………………. 56 j. A New Network………………….………………………………………. 61 k. The People, Leading ……………….…………………………………….. 68 VIII. A Conversation with Wahu Kaara ….……………………………………… 74 IX. Best Practices in Peacebuilding …………………………………………... 81 X. Further Reading – Kenya ………………………………………………….. 87 XI. Biography of a Peace Writer -

Evaluating the Life of Wangari Maathai (1940–2011) Using the Lens of Dark Green Religion

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012). Title of the thesis or dissertation (Doctoral Thesis / Master’s Dissertation). Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/102000/0002 (Accessed: 22 August 2017). EVALUATING THE LIFE OF WANGARI MAATHAI (1940–2011) USING THE LENS OF DARK GREEN RELIGION BY LOUISA JOHANNA DU TOIT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE: MASTER OF ARTS IN BIBLICAL STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR H. VIVIERS JUNE 2019 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation, Evaluating the Life of Wangari Maathai (1940–2011) Using the Lens of Dark Green Religion, is my own work and that all sources used and quoted have been duly recognized and referenced. I also declare that this work or part thereof have not been previously submitted by me at this or any other university. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A journey into the academic world is not a simple one, and one that cannot be attempted without the help and support of others. Since a journey is as much about the trip as about the destination, it presents many unexpected turns and obstacles and provides opportunities to learn more about yourself, others and the subject matter of the research project. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

HIP-HOP LIFE AND LIVELIHOOD IN NAIROBI, KENYA By JOHN ERIK TIMMONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 John Erik Timmons To my parents, John and Kathleen Timmons, my brothers, James and Chris Timmons, and my wife, Sheila Onzere ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of a PhD requires the support of many people and institutions. The intellectual community at the University of Florida offered incredible support throughout my graduate education. In particular, I wish to thank my committee members, beginning with my Chair Richard Kernaghan, whose steadfast support and incisive comments on my work is most responsible for the completion of this PhD. Luise White and Brenda Chalfin have been continuous supporters of my work since my first semester at the University of Florida. Abdoulaye Kane and Larry Crook have given me valuable insights in their seminars and as readers of my dissertation. The Department of Anthropology gave me several semesters of financial support and helped fund pre-dissertation research. The Center for African Studies similarly helped fund this research through a pre-dissertation fellowship and awarding me two years’ support the Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship. Another generous Summer FLAS Fellowship was awarded through Yale’s MacMillan Center Council on African Studies. My language training in Kiswahili was carried out in the classrooms of several great instructors, Rose Lugano, Ann Biersteker, and Kiarie wa Njogu. The United States Department of Education generously supported this fieldwork through a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Award. -

A History of Nairobi, Capital of Kenya

....IJ .. Kenya Information Dept. Nairobi, Showing the Legislative Council Building TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Chapter I. Pre-colonial Background • • • • • • • • • • 4 II. The Nairobi Area. • • • • • • • • • • • • • 29 III. Nairobi from 1896-1919 •• • • • • • • • • • 50 IV. Interwar Nairobi: 1920-1939. • • • • • • • 74 V. War Time and Postwar Nairobi: 1940-1963 •• 110 VI. Independent Nairobi: 1964-1966 • • • • • • 144 Appendix • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 168 Bibliographical Note • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 179 Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 182 iii PREFACE Urbanization is the touchstone of civilization, the dividing mark between raw independence and refined inter dependence. In an urbanized world, countries are apt to be judged according to their degree of urbanization. A glance at the map shows that the under-developed countries are also, by and large, rural. Cities have long existed in Africa, of course. From the ancient trade and cultural centers of Carthage and Alexandria to the mediaeval sultanates of East Africa, urban life has long existed in some degree or another. Yet none of these cities changed significantly the rural character of the African hinterland. Today the city needs to be more than the occasional market place, the seat of political authority, and a haven for the literati. It remains these of course, but it is much more. It must be the industrial and economic wellspring of a large area, perhaps of a nation. The city has become the concomitant of industrialization and industrialization the concomitant 1 2 of the revolution of rising expectations. African cities today are largely the products of colonial enterprise but are equally the measure of their country's progress. The city is witness everywhere to the acute personal, familial, and social upheavals of society in the process of urbanization. -

Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya This Page Intentionally Left Blank Pal-Alam-00Fm.Qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page Iii

pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page i Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya This page intentionally left blank pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page iii Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya S. M. Shamsul Alam, PhD pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page iv Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya Copyright © S. M. Shamsul Alam, PhD, 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quo- tations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN-13: 978-1-4039-8374-9 ISBN-10: 1-4039-8374-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Alam, S. M. Shamsul, 1956– Rethinking Mau Mau in colonial Kenya / S. M. Shamsul Alam. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-4039-8374-7 (alk. paper) 1. Kenya—History—Mau Mau Emergency, 1952–1960. 2. Mau Mau History. I. Title. DT433.577A43 2007 967.62’03—dc22 2006103210 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. -

Democracies Waging Counterinsurgency in a Foreign Context: the Past and Present

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2015 Democracies Waging Counterinsurgency in a Foreign Context: The Past and Present Scott J. Winslow Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Winslow, Scott J., "Democracies Waging Counterinsurgency in a Foreign Context: The Past and Present" (2015). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4475. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4475 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACIES WAGING WAR IN A FOREIGN CONTEXT: THE PAST AND PRESENT by Scott J. Winslow A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Political Science Approved: ________________________ _______________________ Dr. Veronica Ward Dr. Jeannie Johnson Major Professor Committee Member ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Abdulkafi Albirini Dr. Mark McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2015 ii Copyright © Scott Winslow 2015 All Right Reserved iii ABSTRACT Democracies Waging Counterinsurgency in a Foreign Context: The Past and Present by Scott J. Winslow, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2015 Major Professor: Dr. Veronica Ward Department: Political Science Why have Western democracies been successful in conducting external counterinsurgency operations in the past and unsuccessful recently? This thesis conducts a comparison between two successful past interventions, and a recent unsuccessful one using three variable groupings. -

Mau Mau Crucible of War: Statehood, National Identity and Politics in Postcolonial Kenya

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Mau Mau crucible of war: Statehood, national identity and politics in postcolonial Kenya Nicholas Kariuki Githuku Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Githuku, Nicholas Kariuki, "Mau Mau crucible of war: Statehood, national identity and politics in postcolonial Kenya" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5677. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5677 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAU MAU CRUCIBLE OF WAR: STATEHOOD, NATIONAL IDENTITY AND POLITICS IN POSTCOLONIAL KENYA by Nicholas Kariuki Githuku Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Approved by Dr. Robert Maxon, Committee Chairperson Dr. Joseph Hodge Dr. Robert Blobaum Dr. Jeremia Njeru Dr. Tamba M’bayo Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2014 Keywords: war, statehood, stateness, security, mentalité, national identity, psychosociological anxieties Copyright 2014 Nicholas Kariuki Githuku Abstract The postcolonial African state has been the subject of extensive study and scrutiny by various scholars of great repute such as Colin Legum, Crawford Young, Robert H. -

The Mau Mau: Myths and Misrepresentations in US News Media, London School of Economics Undergraduate Political Review, 4(1), 27-42

Silvia Hernandez Benito (2021), The Mau Mau: Myths and Misrepresentations in US News Media, London School of Economics Undergraduate Political Review, 4(1), 27-42 The Mau Mau: Myths and Misrepresentations in US News Media Silvia Hernandez Benito1 1American University, [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this research is to analyze the meanings and ideas evoked by discourses on Africa and the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya in The New York Times (NYT) in order to demonstrate structural biases and operating frameworks that perpetuate negative attitudes towards Africa by representing Africa as synonymous with terror, hopelessness, and conflict. These representations are perpetrated by stereotypes and myths, the four Structural Media biases, and colonial discourses. These biases, in turn, make it difficult to present news from Africa in ways that counter stereotypical ideas. This research paper provides the case of media coverage of the Mau Mau movement in 1950s Kenya, which focused on discrediting the movement by representing them as terrorists, a criminal enterprise, and with links to communism, while never properly explaining the movement. Elite United States (US) newspapers saw national liberation movements as products of the communist influence that threatened US interests post-World War II. This analysis utilizes a methodology rooted in genealogical media approaches, media and post-colonialist theory, structural media framework biases, and African political thought. Such trends help visualize representations of the Mau Mau Uprising and Africa as continuous, while advancing the claim that US news media prioritized the delegitimization of the Mau Mau Uprising. The implications of these representations are the shifting behavior and cultural attitudes towards Africa, and more specifically Kenya. -

Myths and Realities of Minimum Force in British Counterinsurgency Doctrine and Practice

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2013-03 MYTHS AND REALITIES OF MINIMUM FORCE IN BRITISH COUNTERINSURGENCY DOCTRINE AND PRACTICE Boer, Christopher B. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/32796 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS MYTHS AND REALITIES OF MINIMUM FORCE IN BRITISH COUNTERINSURGENCY DOCTRINE AND PRACTICE by Christopher B. Boer March 2013 Thesis Advisor: Douglas Porch Second Reader: Arturo Sotomayor Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202–4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704–0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 2013 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS MYTHS AND REALITIES OF MINIMUM FORCE IN BRITISH COUNTERINSURGENCY DOCTRINE AND PRACTICE 6. AUTHOR(S) Christopher B. Boer 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943–5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

The Dramaturgy of Femi Osofisan Adesola Olusiji ADEYEMI Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor O

The Dramaturgy of Femi Osofisan Adesola Olusiji ADEYEMI Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of English May 2009 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. Acknowledgment This thesis would not have been written without the support and encouragement of … actually, it would have been written, eventually; this work is part of a research of more than twenty years into the work of playwright Femi Osofisan. There have been many encounters along the way – some delightfully pleasant, many enriching and a few downright diversionary; but all provided a worthwhile experience. To Professor Femi Osofisan for allowing me unfettered access into his personal as well as working life; and for trusting my judgement even when I had no idea what I was doing. For all the support over the years, I express my profound gratitude. I thank my supervisor and friend, Professor Jane Plastow, whose patience, support, resources, gentle nudging and affable reprimands helped this thesis immensely. Emeritus Professor Martin Banham, Professors Chris Dunton and Kathryn Kendall, all great teachers, all great mentors; I am indeed a fortunate man to have drunk out of the generosity of your knowledge. There is one person who would not be expecting me to write this; he would be expecting a phone call or a quiet email instead, sometimes, in the dead of the night or at such odd moments when my intrusion battles for attention with a bottle of red claret or the warm embrace of a loving arm. -

Challenges of Nation Building in Africa and the Middle East Note the Uneasy Coexistence of the Modern World and the Traditional World in Africa

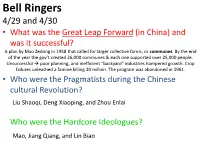

Bell Ringers 4/29 and 4/30 • What was the Great Leap Forward (in China) and was it successful? A plan by Mao Zedong in 1958 that called for larger collective farms, or communes. By the end of the year the gov’t created 26,000 communes & each one supported over 25,000 people. Unsuccessful poor planning, and inefficient “backyard” industries hampered growth. Crop failures unleashed a famine killing 20 million. The program was abandoned in 1961. • Who were the Pragmatists during the Chinese cultural Revolution? Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, and Zhou Enlai Who were the Hardcore Ideologues? Mao, Jiang Qiang, and Lin Biao Ch. 17 Notes • Brinkmanship – A willingness to go to the brink, or edge, of war. *1953 – Eisenhower becomes U.S. President *He appoints John Foster Dulles as secretary of state. *Dulles says if the U.S.S.R. or its supporters attacked the U.S. or their interests, then the U.S. would retaliate immediately! • Détente – a policy of reducing Cold War tensions that was adopted by the U.S. during Richard Nixon’s presidency. This grew out of the philosophy known as realpolitik (realistic politics) aka. Dealing with other nations in a practical/flexible manner. • Francis Gary Powers & the U-2 incident (1960) *Soviets shot down a U-2 plane (CIA high altitude spy flight plane) over Soviet territory. Powers was captured and spent 19 months in prison. This event brings mistrust between the U.S. and Soviets. • Jospi Broz “Marshal” Tito & Yugoslavia Marshal= highest rank of Yugoslav People’s Army & only person to receive it.