ERT Text 26/2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2021 the Monthly Newsletter of Covenant Lutheran Church, ELCA

The Promise The People of Covenant are called to: gather, grow and go serve…With God’s Love! April 2021 The Monthly Newsletter of Covenant Lutheran Church, ELCA Inside This Issue 2. Message from Pastor Sara 3. Message from Council President 4. Congregational Life 5. Education 7. Money Matters 8. Memorials Maundy Thursday: Livestream Youtube 9. Health Topics worship. 7pm https://youtu.be/ 11. Blood Drive sIHdrKS8VvE 12. Foundation Scholarships 13. Property News 15. Covenant News 16. Social Justice 17. Thank yous Co mm 18. Contact Information Easter Worship: Livestream Youtube worship. 9:30am https://youtu.be/kZc_3dBCTpE 1 Covenant Lutheran Church, 1525 N. Van Buren St., Stoughton, WI 53589 Message from Pastor Sara Easter always falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox. “Easter” seems to go back to the name of a pre-Christian goddess in England, Eostre, who was celebrated at beginning of spring and fertility. The only reference to this goddess comes from the writings of the Venerable Bede, a British monk who lived in the late seventh and early eighth century. Christians observed the day of the Crucifixion on the same day that Jews celebrated the Passover offering—that is, on the 14th day of the first full moon of spring. The Resurrection, then, was observed two days later, on 16 Nisan, regardless of the day of the week. In the West the Resurrection of Jesus was celebrated on the first day of the week, Sunday, when Jesus had risen from the dead. Consequently, Easter was always celebrated on the first Sunday. -

ANNUAL REPORT Hon

PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Margaret MacPherson Terri Ross FIRST VICE PRESIDENT DIRECTOR OF FISCAL SERVICES Hon. Raymond J. Irrera Bonnie Ng VICE PRESIDENTS DIRECTOR OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES Nancy Glass Joseph A. Cristiano, Esq. ANNUAL REPORT Hon. David Elliot DIRECTOR OF ADULT SERVICES Hon. Tarek M. Zeid Edward T. Weiss 2019-20 ACTIVE PAST PRESIDENTS DIRECTOR OF RESIDENTIAL SERVICES Hon. George E. Berger Stacy Accardi John J. Governale Ending 6/30/2020 DIRECTOR OF CLINICAL SERVICES Michael J. Macaluso Marisa Fojas, LCSW Hon. Natalie Rogers Jack M. Weinstein, Esq. DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Wendy Phaff Gennaro SECRETARY DIRECTOR OF HUMAN RESOURCES Patricia Coulaz Harriet L. Perry TREASURER DIRECTOR OF BELLEROSE DAY SERVICES Thomas N. Toscano, Esq. Geraldine Feretic BOARD OF DIRECTORS DIRECTOR OF 164TH ST. DAY SERVICES Gerald J. Caliendo Josie Davide Raymond Chan Anthony S. Cosentino DIRECTOR OF VOCATIONAL SERVICES Kate Valli Franz Gritsch Hon. James Kilkenny DIRECTOR OF QUALITY IMPROVEMENT & William D. Martin SYSTEMS INTEGRATION Nancy Vargas Ellen J. Arocho DIRECTOR OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Syed Asif QCP Adult Center QCP Bellerose Center QCP Children's Center 81-15 164th Street 249-16 Grand 82-25 164th Street 81-15 164 Street, Jamaica NY 11432 Jamaica, NY 11432 Central Parkway Jamaica, NY 11432 Bellerose, NY 11426 Telephone: (718) 380-3000 Tel. 718-380-3000 Tel. 718-279-9404 Tel. 718-374-0002 Visit our website: www.queenscp.org Fax 718-380-0483 Fax 718-423-1404 Fax 718-380-3214 Like us on Facebook: Facebook.com/QueensCP A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR And BOARD PRESIDENT SERVICES Our lives changed in mid-March 2020. -

Tarrant County College District Spring 2021 Candidates for Graduation 1 | Page

Tarrant County College District Spring 2021 Candidates for Graduation Honors Codes: HH-Highest Honors, HI-High Honors, HO-Honors, GD-Graduation with Distinction - Explanation Awards will be posted upon completion of verification processes; honors designations subject to change. Note: Not all graduates listed due to individual preference. Diploma Name Degree or Certificate Title Honors Code Patrick D. Abair CRT Aviation Maintenance Technology Airframe Patrick D. Abair AAS Aviation Maintenance Technology Airframe Asma Ghulam Abbas AA Associate of Arts HO Alejandro M. Abdala AA Associate of Arts Sylvia S. Abdelmasih AA Associate of Arts Omnia Izzeldeen Abdelwahab AA Associate of Arts HO Areej Fatih Abdo AAT Associate of Arts in Teaching (E-6) Naydelin Abdul AA Associate of Arts Dalya Q. Abdulateef AA Associate of Arts Jaya Cecil Abito AA Associate of Arts HI Emmanuel J. Abrego AAS Diagnostic Medical Sonography HO Adriana Acevedo AAS Nuclear Medicine Technology Angela M. Acosta CRT Transportation Management Angela M. Acosta CRT Warehouse Management Estefani O. Acosta AA Associate of Arts Daniel A. Gallard Adames AAS Aviation Technology - Professional Pilot Amy Denise Adams CRT Accounting Assistant I Christian B. Adams AAS Nursing Dirk E. Adams AA Associate of Arts Lauren T. Adams AA Associate of Arts Richard L. Adams CES Flight Instructor GD Richard L. Adams AA Associate of Arts HI Richard L. Adams AAS Aviation Technology - Professional Pilot HI Jasmine Lizbeth Adan AAT Associate of Arts in Teaching (E-6) Sheila Addo AA Associate of Arts Oluwatobiloba Adedeji AAS Accounting Information Management Ifeoluwa Sandra Adeniyi AA Associate of Arts Latorya Michelle Adeniyi AAS Graphic Communication Latorya Michelle Adeniyi CRT Computer Graphics Olufunke M. -

N°1/2013 Cine Video Radio Internet Television

CINE VIDEO N°1/2013 Publication trimestrielle multilingue RADIO Multilingual quarterly magazine Revista trimestral multilingüe INTERNET TELEVISION ISSN 0771-0461 - Publication trimestrielle 2013 Avril 4 - 1040 Bruxelles de Poste Bureau Notebook Christian. At the family estate there is a chapel, in which evil is overcome. Discovering that he is an orphan offers an explanation why he is so attached to his new “family” which is the secret service and M... a surrogate mother. Finally Bond is portrayed as a man who takes responsibility and wants to sacrifice himself for the well-being of others. Besides the review by Vallini there are four other articles on the film. GC 2012 St. Francis de beaucoup de femmes une icône de la liberté et de Sales Award – Helen la persévérance. Osman, Secretary for Communications at Educar para la Paz – Con el lema “La paz para the U.S. Conference todos nace de la justicia de cada uno” el Certamen Skyfall and l’Osservatoro Romano – On of Catholic Bishops Educar para la Paz cumple 10 años. Destinado a October 31st 2012 L’Osservatore Romano published and a former diocesan alumnos de entre 6 y 18 años de escuelas de gestión several articles on the latest James Bond film communications pública y privada de toda la geografía Argentina, which premiered on Italian screens that day. It director and el concurso es organizado conjuntamente por became world news and the international press newspaper editor, is the winner of the Catholic la Acción Católica y la Asociación Cristiana gave considerable attention to it. Skyfall and Press Association’s 2012 St. -

Annual Giving Report July 1, 2014 - June 30, 2015 Alumni Class Giving the Generosity of Our Alumni Keeps MMA Strong

ANNUAL GIVING REPORT July 1, 2014 - June 30, 2015 Alumni Class Giving The generosity of our alumni keeps MMA strong. Every gift of every size is a voice of support. Thank You. 1943-1 67% 1950 42% Roscoe P. McEacharn 1958 36% 1961 31% Philip J. Adams Robert G. Bent Carl R. Morris John W. Bitoff Carl S. Akin Edgar W. Dorr Dwight R. Blodgett Robert W. Nason Everett A. Cooper James W. Burroughs Chester F. Fossett Richard D. O’Leary Ward E. Cunningham Thomas J. Cartledge 1943-2 46% Luther M. Goff Winslow S. Pillsbury James D. Dee Stewart M. Farquhar William F. Brennan Emerson L. Hansell Thomas M. Raymond David W. Farnham Ernold R. Goodwin Harold F. Burr Joseph G. Leclair Sullivan W. Reed Manuel A. Hallier Jerome M. Gotlieb Richard M. Burston Robert B. Lessels John V. Sawyer R. Edward Hanson William K. Gribbin Frank E. Hall Lloyd D. Lowell John R. Spear Gerhard M. Hoppe John E. Haramis Carlton L. Hutchins Richard L. MacLean Ace F. Trask Peter B. Kropotkin Ralph Hayden Frederick Leone Richard E. Marriner Russell D. Myers Herbert P. Leyendecker William B. Melaugh Richard C. O’Donnell 1955 38% Norris M. Reddish Kenneth A. Smith Fred J. Merrill Peter A. Scontras Heinrich W. Bracker Walter K. Seman Eugene H. Spinazola Gerard L. Nelson Louis Zulka Lawrence Johnson Robert P. Sullivan Richard G. Spear James S. KomLosy 1959 94% David C. Wentworth Clifford Stowers 1951 47% Ronald A. Marquis Paul P. Borde Warren W. Strout Richard M. Anzelc Donald L. Merchant Winfred H. Bulger 1962 37% Richard P. -

In Lawsuit; R ^ L

In Lawsuit; r ^ l. XCW. No. 124 — Manchestor, Conn., Monday, FeDriiary 2fi, iflM • Since 1881 • 20$ Single Copy • 15c Home Delivered Funds Safe By MARY KITZMANN withdrawal from the Community Riots Herald Reporter Development Block Grant program MANCHESTER - The Hartford is an attempt to limit low-income and City Council appears to plan to re minority housing. main in the Community Develop It is a part of the court case started ment Block Grant lawsuit while plan by three Manchester residents and Cover joined by the U.S. Department of ning no further action in its request to withhold J4.5 million in Justice. Manchester federal funds. The Hartford City Council filed the Resolutions which are before the brief and also requested five federal Kabul council tonight, support the “friend agencies withhold $4.5 million in of the court’’ brief filed by the funds from Manchester. In a Nov. 28 letter to the Hartford John lives By Lniled Press International previous council. The two resolutions, submitted by Antoinette City Council Stephen Penny, indy Springs The Afghan capital of Kabul, Manchester’s mayor, requested the partment in Leone, councilwoman, and Robert already disrupted by four days of council to withdraw these com Fernando anti-Soviet protests, was hit today by Ludgin, deputy mayor, state the when “The council’s intent to let the brief re plaints, but did not address the court a wave of rioting, looting, and gun brief. ” is filming. fire, Radio Kabul said in a rare ad main in court files. , New York, “The important thing is what the mission of trouble in the mile-high ci Another resolution, submitted by ing. -

537E34d0223af4.56648604.Pdf

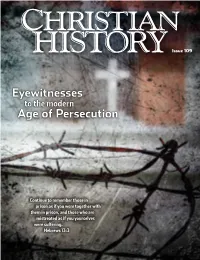

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 109 Eyewitnesses to the modern Age of Persecution Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering. Hebrews 13:3 RARY B I L RT A AN M HE BRIDGE T COTLAND / S RARY, B I L RARY B NIVERSITY I U L RT A AN LASGOW M G “I hAD TO ASK FOR GRACe” Above: Festo Kivengere challenged Idi Amin’s killing of Ugandan HE BRIDGE Christians. T BOETHIUS BEHIND BARS Left: The 6th-c. Christian ATALLAH / M I scholar was jailed, then executed, by King Theodoric, N . CHOOL (14TH CENTURY) / © G an Arian. S RARY / B TALIAN I I L ), Did you know? But soon she went into early labor. As she groaned M in pain, servants asked how she would endure mar- CHRISTIANS HAVE SUFFERED FOR tyrdom if she could hardly bear the pain of childbirth. , 1385 (VELLU She answered, “Now it is I who suffer. Then there will GOSTINI PICTURE A THEIR FAITH THROUGHOUT HISTORY. E be another in me, who will suffer for me, because I am D HERE ARE SOME OF THEIR STORIES. also about to suffer for him.” An unnamed Christian UM COMMENTO woman took in her newborn daughter. Felicitas and C SERVING CHRIST UNTIL THE END her companions were martyred together in the arena Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, is one of the earliest mar- in March 202. TALY, 16TH CENTURY / I tyrs about whom we have an eyewitness account. In HILOSOPHIAE P E, M the second century, his church in Smyrna fell under IMPRISONED FOR ORTHODOXY O great persecution. -

St. Anne Catholic Church

Parish Office Hours Welcome to St. Anne Tuesday through Thursday: 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday Worship: Saturday 5:15 p.m., Sunday: 9:15 a.m. &-11:30 a.m. Friday: 8:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. Eucharistic holy hour Tuesday 7 to 8 p.m. 262-942-8300 Catholic Schools www.allsaintskenosha.org www.kenoshastjoseph.com Kenosha Area Young Adult Catholics: Facebook: KYAC Daily Masses: 1st Tuesday of month 5:15 p.m. St. Catherine Medical Center Chapel All other Tuesdays 5:15 p.m. St. Anne Wednesday, Thursday, Friday , - 12 noon St. Anne Saturdays 8:30 a.m. St. Anne 2nd Wednesday 10:15 a.m. Prairie Ridge Sr. Campus 7900 94th Avenue 2nd Friday-10:15 a.m. Brookdale Pleasant Prairie 7377 88th Avenue Please see calendar inside for specifics for the week Baptisms - Congratulations! Contact the parish at least 2 months in advance to register for a Baptism Reflection Weddings-Blessings! Contact Fr. Bob at least 6 months in advance Reconciliation Wednesday 12:30 p.m. Saturday 9 a.m. or by appointment Anointing of the Sick Contact Fr. Bob 942-8300 Parish Membership- Registration will take place after the Sunday, 9:15 a.m. Masses Find us on Facebook: St. Anne Catholic Church, Pleasant Prairie Homilies are posted weekly on our Web site Find us at www.saint-anne.org Parish Calendar & Bulletins Videos Weekly Gospel Reflections Youth Ministry, GRACE Group & That Man is You Updates No Comparisons How many times have we read or heard about someone who’s gotten This Week at St. -

St. a Nthony Parish

JUNE 27, 2021 Offices Closed July 5, Monday, in Observance of Independence Day No Staff at PMC Office. ~ All parish offices remain closed until further notice ~ We will have the CHURCH OPEN for Personal Prayer Times and Confessions Fr. Bazil will be available during these times to respond to your needs. SEE INSIDE BULLETIN FOR SCHEDULES The west door code access will be shut off. The entrance to the west door will be open ONLY during the hours mentioned on schedule. For emergencies during off hours, call 4252727602. Please visit the St. Anthony Parish website www.stanthony.cc St. Anthony Parish Parish St. Anthony for more information, upcoming Live Stream Masses, and updates. 1 TljNJǓǕdždžǏǕlj SǖǏDžǂǚ In Ordinary Time I will praise You, Lord, for You have rescued me. "If the only prayer you ever say in your entire life is thank you, it will be enough." Meister Eckhart Dear Friends, With a heart full of gratitude I say, “Thank you!” These last six years have been quite the journey here at St. Anthony. We have weathered many a storm and the Lord has been at work through it all. I have been surprised time and again as I hear your stories about how God has worked in these years to draw you closer to Him. Many of these stories I am hearing for the first time now and it is so amazing to be able to reflect on how present and faithful God has been through everything. As we remember, the memory stirs up the encounter and it becomes present to us again. -

Michigan State University Commencement Spring 2021

COMMENCEMENT CEREMONIES SPRING 2021 “Go forth with Spartan pride and confdence, and never lose the love for learning and the drive to make a diference that brought you to MSU.” Samuel L. Stanley Jr., M.D. President Michigan State University Photo above: an MSU entrance marker of brick and limestone, displaying our proud history as the nation’s pioneer land-grant university. On this—and other markers—is a band of alternating samara and acorns derived from maple and oak trees commonly found on campus. This pattern is repeated on the University Mace (see page 13). Inside Cover: Pattern of alternating samara and acorns. Michigan State University photos provided by University Communications. ENVIRONMENTAL TABLE OF CONTENTS STEWARDSHIP Mock Diplomas and the COMMENCEMENT Commencement Program Booklet 3-5 Commencement Ceremonies Commencement mock diplomas, 6 The Michigan State University Board of Trustees which are presented to degree 7 Michigan State University Mission Statement candidates at their commencement 8–10 Congratulatory Letters from the President, Provost, and Executive Vice President ceremonies, are 30% post-consumer 11 Michigan State University recycled content. The Commencement 12 Ceremony Lyrics program booklet is 100% post- 13 University Mace consumer recycled content. 14 Academic Attire Caps and Gowns BACCALAUREATE DEGREES Graduating seniors’ caps and gowns 16 Honors and master’s degrees’ caps and 17-20 College of Agriculture and Natural Resources gowns are made of post-consumer 21-22 Residential College in the Arts and Humanities recycled content; each cap and 23-25 College of Arts and Letters gown is made of a minimum of 26-34 The Eli Broad College of Business 23 plastic bottles. -

Parish Priest Accused of Rape by His 18

Rihanna tweets down talk of sex tape Rihanna may like to sing about sex and she may like to Article wear sexy costumes on stage, but the "S&M" singer says there is no videotape of... Home Nation Regions Business Pinoy Abroad World Sports Showbiz Lifestyle Technology Special Features Humor More sections UST beats UE, bolsters chances for 2nd finals spot Advertise with us Home > Regions > Top Stories Parish priest accused of rape by his 18-year-old » Social welfare officer: Agusan Norte rape helper victim goes 'missing' 08/28/2011 | 09:12 AM » Agusan Norte Catholic priest denies charges of rape Recommend 34 Send 0 61 » 18-year-old helper accuses Catholic priest of rape An 18-year-old woman has filed a complaint with public prosecutors in Agusan del Norte that a parish priest whom she had served as a domestic helper repeatedly raped her earlier » Teachers clamor for hazard pay in wake of this year. Agusan hostage crisis Recent sex scandals in PHL » Police see Agusan hostage crisis over this The priest, Fr. Raul Cabonce, has reportedly sought Catholic Church Sunday In 2008, 15-year-old girl "Crystal" refuge in the Bishop's residence in Butuan City and could (not her real name) accused Fr. » Suspected rebels attack Agusan Norte police not be reached for comment, but has previously denied Gabriel Madangeng Jr of raping her camp the allegations. from August to December 2006. » Taiwanese, companion lose P300K to The girl eventually filed five counts muggers in Butuan The complainant said in her affidavit filed last Thursday of rape and seven counts of acts of » Police: 2 people drown in Agusan del Norte that Father Cabonce had offered her a scholarship in lasciviousness against the priest. -

Argentina Pleads for U.N. Role

New law may help Woman adjusts iign tb e^w ^ area credit unions to man's worick Kentucky Derby page 9 ... page 20 / page 16 Manchester, Conn. Warm, sunny ■ Saturday, May 1, 1982 today and Sunday Single copy 25c — See pc^ie 2 y - • y Argentina f*.' pleads for \. ■ \ U.N. role UNITED NATIONS (UPI) - contingency plan for future media Denying Argentina had rejected a tion and a possible U.N. “ presence” U.S. peace plan, Argentine Foreign on the islands. Minister Nicanor Costa Mendez said Costa Mendez met with Secretary- Friday his country ready to General Javier Perez de Cuellar and accept a U.N. resolution calling for said afterwards he favored media its withdrawal from the Falklands — tion by the U.N. chief. but only if Britain accepts the jun Diplomats said it was not im ta’s claim to sovereignty. mediately clear if Costa Mendez’ Costa Mendez also called for U.N. statements represented an Argen intervention in the Falklands dis tine retreat or a diplomatic attempt pute to head off a war that seemed to gain more time before Britain imminent. and Argentina came to blows over Costa Mendez spoke to reporters the islands Argentina seized April 2. momements after Secretary of British warships, battling moun State Alexander Haig announced in tainous waves in the stormy South Washington that the United States Atlantic, clamped an air and sea was dropping its neutrality, siding blockade around the Falklands, 450 with Britain and imposing military miles off the Argentine coast, at 7 and economic sanctions against a.m.