Dress Codes: an Analysis of Gender in High

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Crossdressing Cinema: an Analysis of Transgender

CROSSDRESSING CINEMA: AN ANALYSIS OF TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION IN FILM A Dissertation by JEREMY RUSSELL MILLER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2012 Major Subject: Communication CROSSDRESSING CINEMA: AN ANALYSIS OF TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION IN FILM A Dissertation by JEREMY RUSSELL MILLER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, Josh Heuman Aisha Durham Committee Members, Kristan Poirot Terence Hoagwood Head of Department, James A. Aune August 2012 Major Subject: Communication iii ABSTRACT Crossdressing Cinema: An Analysis of Transgender Representation in Film. (August 2012) Jeremy Russell Miller, B.A., University of Arkansas; M.A., University of Arkansas Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joshua Heuman Dr. Aisha Durham Transgender representations generally distance the transgender characters from the audience as objects of ridicule, fear, and sympathy. This distancing is accomplished through the use of specific narrative conventions and visual codes. In this dissertation, I analyze representations of transgender individuals in popular film comedies, thrillers, and independent dramas. Through a textual analysis of 24 films, I argue that the narrative conventions and visual codes of the films work to prevent identification or connection between the transgender characters and the audience. The purpose of this distancing is to privilege the heteronormative identities of the characters over their transgender identities. This dissertation is grounded in a cultural studies approach to representation as constitutive and constraining and a positional approach to gender that views gender identity as a position taken in a specific social context. -

The Morgue File 2010

the morgue file 2010 DONE BY: ASSIL DIAB 1850 1900 1850 to 1900 was known as the Victorian Era. Early 1850 bodices had a Basque opening over a che- misette, the bodice continued to be very close fitting, the waist sharp and the shoulder less slanted, during the 1850s to 1866. During the 1850s the dresses were cut without a waist seam and during the 1860s the round waist was raised to some extent. The decade of the 1870s is one of the most intricate era of women’s fashion. The style of the early 1870s relied on the renewal of the polonaise, strained on the back, gath- ered and puffed up into an detailed arrangement at the rear, above a sustaining bustle, to somewhat broaden at the wrist. The underskirt, trimmed with pleated fragments, inserting ribbon bands. An abundance of puffs, borders, rib- bons, drapes, and an outlandish mixture of fabric and colors besieged the past proposal for minimalism and looseness. women’s daywear Victorian women received their first corset at the age of 3. A typical Victorian Silhouette consisted of a two piece dress with bodice & skirt, a high neckline, armholes cut under high arm, full sleeves, small waist (17 inch waist), full skirt with petticoats and crinoline, and a floor length skirt. 1894/1896 Walking Suit the essential “tailor suit” for the active and energetic Victorian woman, The jacket and bodice are one piece, but provide the look of two separate pieces. 1859 zouave jacket Zouave jacket is a collarless, waist length braid trimmed bolero style jacket with three quarter length sleeves. -

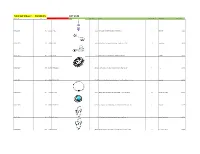

Total Lot Value = $5,520.15 LOT #149 Location Id Lot # Item Id Sku Image Store Price Model Store Quantity Classification Total Value

Total Lot Value = $5,520.15 LOT #149 location_id Lot # item_id sku Image store_price model store_quantity classification Total Value A10-S11-D009 149 143692 BR-2072 $11.99 Pink CZ Sparkling Heart Dangle Belly Button Ring 1 Belly Ring $11.99 A10-S11-D010 149 67496 BB-1011 $4.95 Abstract Palm Tree Surgical Steel Tongue Ring Barbell - 14G 10 Tongue Ring $49.50 A10-S11-D013 149 113117 CA-1346 $11.95 Triple Bezel CZ 925 Sterling Silver Cartilage Earring Stud 6 Cartilage $71.70 A10-S11-D017 149 150789 IX-FR1313-10 $17.95 Black-Plated Stainless Steel Interlocked Pattern Ring - Size 10 1 Ring $17.95 A10-S11-D022 149 168496 FT9-PSA15-25 $21.95 Tree of Life Gold Tone Surgical Steel Double Flare Tunnel Plugs - 1" - Pair 2 Plugs Sale $43.90 A10-S11-D024 149 67502 CBR-1004 $10.95 Hollow Heart .925 Sterling Silver Captive Bead Ring - 16 Gauge CBR 10 Captive Ring , Daith $109.50 A10-S11-D031 149 180005 FT9-PSJ01-05 $11.95 Faux Turquoise Tribal Shield Surgical Steel Double Flare Plugs 4G - Pair 1 Plugs Sale $11.95 A10-S11-D032 149 67518 CBR-1020 $10.95 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Star Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 4 Captive Ring , Daith $43.80 A10-S11-D034 149 67520 CBR-1022 $10.95 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Butterfly Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 2 Captive Ring , Daith $21.90 A10-S11-D035 149 67521 CBR-1023 $8.99 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Cross Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 2 Captive Ring , Daith $17.98 A10-S11-D036 149 67522 NP-1001 $15.95 Triple CZ .925 Sterling Silver Nipple Piercing Barbell Shield 8 Nipple Ring $127.60 A10-S11-D038 149 -

Carnival Is Great Success; June Fourth Marks Prom; Profits Go To

Vol, XXK—No. 20 Paul D. Schreiber High School, Port Washington, N. Y., May 27, 1955 PRICE: TEN CENTS Carnival Is Great Success; June Fourth Marks Prom; Profits Go To Scholarships 'Sand And The Sea^ Is Title "I am more than pleased with the response I got from the June 4 night, the junior class will present "The Sand and the faculty, students and community," said Mr. Scott about the very Sea," the annual Junior From, to be held in the cafeteria of PDSHS. Roy Darnell and his band will play from 9 to 1. Admission to this successful Spring Carnival held last Saturday on the athletic field. — formal dance is $3.00. Highlight• Well over $3,000 was made at ing the evening will be dancing the carnival but the bills have Prospects For 1955-56 on the terrace and the crowning yet to be subtracted from this of a king and queen who will figure. All proceeds will go by Seamus McGrady be chosen from students in the toward student scholarships. junior class. After elections, victorious politicans usually try to forget their Officers of the junior class, Carnival Queen Sherry Wal- campaign promises. thers picked the winning chance, Ray Saulter, president; Eddie The Pilots don't. Lloyd, vice-president; Sue Dorn, worth $200.00, which belonged to These are what we promised, and this is what has happened: secretary; and Frank Cifarelli, Ralph Innella. Chance book CLAY TENNIS COURTS: Dr. Hall says construction will start treasurer are in charge of the sales reached 1400 books with this summer; dance. -

Does Your Apparel Supply Chain Need a Logistics Makeover?

Does Your Apparel Supply Chain Need a Logistics Makeover? ©2018 Purolator International, Inc. Does Your Apparel Supply Chain Need A Logistics Makeover? Introduction When then J.Crew Chief Executive Officer Mickey These changing expectations are driven largely by regions. For most apparel makers, this includes Drexler was asked to describe his apparel the increasing role of eCommerce and, specifically, suppliers located in China as well as Vietnam. company’s typical customer, he responded with: the tremendous impact amazon.com is having on Sprawling supply chains have helped create “She’s loyal as hell until we go wrong. Then she the apparel industry. Financial services firm Cowen long lead times – currently it takes as long as 15 wants it on sale.” and Company expects Amazon to overtake months to bring a new concept to market. Macy’s as the largest U.S. apparel retailer by the Drexler’s simple, albeit blunt, observation would An added concern includes threats of increased end of the 2018, with consumers increasingly seem to describe consumer attitudes across trade restrictions between the United States, turning to Amazon as a “go-to” source for basics the entire apparel and accessories market. China, and other nations. Both China and the including T-shirts, jeans and underwear. In fact, Today’s consumers have heightened expectations United States have proposed new tariffs on goods Amazon’s top-selling apparel items during 2017 about virtually every aspect of their apparel- traveling between the two countries, which could included ASICS men’s running shoes, Levi’s men’s buying experiences: significantly drive up the cost of fabrics and other regular fit jeans, and UGG women’s boots. -

Character Costume Items to Be Provided by Families

Class Class Class Teacher Role/ Costume items to be provided by families & special instructions from Day Time Type Character teachers Monday 4:00 pm Tap & Creative Lisa Swedish Fish Ballet shoes. Light pink footed ballet tights. Black leotard. Dance (Age 3) Monday 4:15 pm Jazz I (age 7-8) Kelly Librarians Blue jeans you can dance in, black tap shoes, solid bright color crew socks (no logos, designs, or embellishments). Monday 4:25 pm Ballet V (Ages Kim Musical Notes Black class leotard. Bright, solid-colored footed tights, any color. Ballet shoes. 11-15) Monday 4:50 pm Tap & Creative Lisa Glow Worms Girls: Black leotard, no skirt. Pink footed ballet tights. Ballet shoes. Boys: bright, Dance (Age 4) solid-colored t-shirt. Black leggings/sweat pants. Ballet shoes. Monday 5:00 pm Tap I (Age 7-8) Kelly James Blue jeans you can dance in, black tap shoes, solid bright color crew socks (no logos, designs, or embellishments). Tuesday 4:00 pm Tap & Pre-Ballet Posy Glow Worms Pink footed ballet tights, any bright solid-colored leggings, any bright solid-colored (Age 4) leotard, pink ballet shoes. Tuesday 4:15 pm Ballet III (Ages Faith BFG's friend Any light blue knee length dress with black class leotard worn underneath. Pink 9-13) footed ballet tights. Pink ballet shoes. Dress example: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B018J4D8UM?psc=1&redirect=true&ref_=ox_s c_act_title_1&smid=ATVPDKIKX0DER Hair firmly secured in proper ballet bun at the crown of the head with headpiece (provided by Danceworks) secured above. Make-up that highlights the eyes, cheeks, and lips. -

FIREMAN HAT, DIAPER COVER, BOOTS and SUSPENDERS PATTERN by Expertcraftss

FIREMAN HAT, DIAPER COVER, BOOTS AND SUSPENDERS PATTERN by ExpertCraftss http://www.etsy.com/shop/ExpertCraftss Email: [email protected] Thank you for purchasing this pattern! If you have any questions, please don't hesitate to contact as above. Good luck and have fun creating this fun set! Maria Pickard MATERIALS NEEDED: H hook, I hook and J hook, depending on the size you wish to make. Red, black and silver yarn. I use "I love this yarn" medium worsted weight. I have also used red heart yarn which actually allows the hat to be a bit more sturdy but is definitely not as soft on baby. Buttons: 2 large for front of diaper cover. 4 smaller buttons for inside diaper cover so that suspenders can be attached. Size of buttons is related to your stitching and what will best fit and hold the flaps and suspenders in place. I try to get the largest button that will fit through stitching for front, 1 inch. There are no specific button holes so test your buttons. I force my buttons through so I know they will not slip out when on baby. Tapestry needle. Difficulty: Intermediate. Stitches used: Ch, sc, hdc, dc, FPdc, sl st. HAT: For newborn use H hook. For 3-6 month, use I hook. For 6-9 month, use I hook and follow directions in bold below. For 9-12 month, use J hook. Magic circle. 1. Ch 2, 8 dc in ring. Slip st to 1st dc. 8 st. 2. Ch 2, dc in same st as sl st. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

DRAPE: Dressing Any Person

DRAPE: DRessing Any PErson Peng Guan1;∗ Loretta Reiss1;∗ David A. Hirshberg2;y Alexander Weiss1;∗ Michael J. Black1;2;y; z 1Dept. of Computer Science, Brown University, Providence 2Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems, Tubingen¨ Figure 1: DRAPE is a learned model of clothing that allows 3D human bodies of any shape to be dressed in any pose. Realistic clothing shape variation is obtained without physical simulation and dressing any body is completely automatic at run time. Abstract 1 Introduction We describe a complete system for animating realistic clothing Clothed virtual characters in varied sizes and shapes are necessary on synthetic bodies of any shape and pose without manual inter- for film, gaming, and on-line fashion applications. Dressing such vention. The key component of the method is a model of cloth- characters is a significant bottleneck, requiring manual effort to de- ing called DRAPE (DRessing Any PErson) that is learned from a sign clothing, position it on the body, and simulate its physical de- physics-based simulation of clothing on bodies of different shapes formation. DRAPE handles the problem of automatically dressing and poses. The DRAPE model has the desirable property of “fac- realistic human body shapes in clothing that fits, drapes realistically, toring” clothing deformations due to body shape from those due and moves naturally. Recent work models clothing shape and dy- to pose variation. This factorization provides an approximation to namics [de Aguiar et al. 2010; Feng et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010] the physical clothing deformation and greatly simplifies clothing but has not focused on the problem of fitting clothes to different synthesis. -

Shelter Point ~ March 2018

October 2012 Debbie Halusek: Activity Director MPR-Multi Purpose Room C-Chapel Please Call: 162 for assistance Shelter Point ~ March 2018 IA-Independent Activity SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Evening Activities 1) 2) 3) March Birthday’s 10:00 Stretch & Strength 10:00 Stretch & Strength 10:00 Rise & Shine-400 Jerlean H. 3-6 Sarah S. 3-24 10:30 Joke Time 10:30 Rise & Shine 10:30 Stretch Tuesdays: Mary A. 3-10 James H. 3-26 11:00 Making Bread/Snack Time 11:00 Snack Time Calendars are & Strength-400 6:30 Bingo Frank H. 3-15 Betty B. 3-29 11:30 Toss & Talk 11:30 Sing A Long 11:00 Snack Time Iola W. 3-15 Doris B. 3-29 7:00 Relaxing Rhythms Subject 2:00 Bingo 2:00 Reminisce 11:30 Sing A Long Edith P. 3-17 Scott G. 3-30 3:00 Bread/Ice Cream Social 2:30 Noodle Ball Pryse F. 3-21 Dorothy S. 3-30 To change. 1:30 Hoy-400 3:30 Pong Toss 3:00 Ice Cream Social Shari Houze 3-21 Dean M. 3-30 4:30 Beauty Spot 3:30 Table Top Bowling Addie F. 3-22 4:30 Color Me Fun 4) 5 ) 6) 7) 8) 9 ) 10) 10:00 Rise & Shine-400 10:00 Stretch & Strength 10:00 Stretch & Strength 10:00 Stretch & Strength 10:00 Stretch & Strength 10:00 Star Glazers 10:00 Rise & Shine-400 10:30 Reminisce-400 10:30 Rise & Shine 10:30 Joke Time 10:30 Rise & Shine 10:30 Joke Time Ceramics 10:30 Stretch 11:30 Catholic 11:00 Snack Time 11:00 Snack Time 11:00 Snack Time 11:00 Snack Time 11:00 Snack Time & Strength-400 Communion 11:15 Beauty Spot 11:30 Reminisce 11:15 Beauty Spot 11:30 Toss & Talk 11:30 Sing A Long 11:00 Snack Time 1:30 Bingo-400 11:45 Sing A Long 2:00 Catholic Communion-C 2:00 Making A Quilt-MPR 2:00 Bingo 2:00 Reminisce 11:30 Sing A Long 2:00 Bingo 2:00 Music: Mr. -

Bikini Arrests, 1940-1960

W A V E R L E Y C O U N C I L BIKINI WARS A W a v e r l e y L i b r a r y L o c a l H i s t o r y F a c t S h e e t Although two piece swimsuits of keeping the costume in have been around since position. Ancient Rome (mosaics While it is impossible to say depicted found in the Villa who was the first to wear the Romana del Casale showed risqué bathing suit to Bondi women wearing bandeau tops Beach, there has been a history and shorts to compete in of arrests of women who dared sports), the bikini as we to breach the 1935 ordinance recognise it is commonly on swimming costumes. credited to French engineer Louis Réard in 1946. According to a Sunday However, the humble bikini has Telegraph report seen its share of controversy in 1946, an unnamed woman over the last 75 years. braved Bondi promenade wearing a bikini and ‘caused a In Waverley, bathing suits near riot’. Waverley Council needed to meet stringent Lifeguard (then known as measurement requirements to Beach Inspectors) Aub Laidlaw be allowed on public beaches. told her she was indecently The Local Government attired and ordered her to the Ordinance No. 52 (1935) changing sheds at Bondi indicated that both men and Pavilion with instructions to put women’s costumes must have on some more clothes. legs at least 3" long, must Later charged with offensive completely cover the front of behaviour, this was just one of the body from the level of the many events in the armpits to the waist, and have subsequent fight against ‘public shoulder straps or other means indecency’.