Cultural Consensus of Felt Love Experiences in Emerging Adulthood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

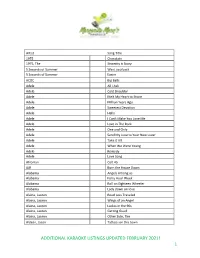

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder, and “I Feel Love”

Thamyris/Intersecting No. 26 (2013) 43–54 Turning the Machine into a Slovenly Machine: Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder, and “I Feel Love” Tilman Baumgärtel The track “I Feel Love” by Donna Summer still seems to come out of another world. Even though the song was produced three decades ago, it still sounds alien and futurist. And the world, out of which “I Feel Love” came, has been built out of loops, nothing but loops. The song rattles on and on like a machine gun. The loops appear deceptively simple at first. “I Feel Love” is based on the electronic throb of a pattern out of a few synthesizer notes the sequencer repeats over and over and occasionally transposes. But in the framework of these minimalist preconditions the track develops a field of rhythmic differences, deviations, and shifts. The blunt, mechanical thumping of a machine turns into complex polyrhythms, strict rule turns into confusing diversity, and eventually becomes an organism out of repetitions. Even Donna Summer herself eventually got lost in the confusing labyrinth of rhythms in “I Feel Love.” In this essay I want to show how producer Giorgio Moroder succeeded in trans- forming the clatter of the synthesizer loops of “I Feel Love” into an organic pulse with the help of a relatively simple production trick. Then, I want to discuss how “I Feel Love” systematically dissolves and collapses antithetical oppositions. This pro- duction trick not only lends an organic quality to the mechanical loops, but, in the process, amalgamates nature and technology on a musical level. -

Lasting-Love-At-Last-By-Amari-Ice.Pdf

Lasting Love at Last The Gay Guide to Attracting the Relationship of Your Dreams By Amari Ice 2 Difference Press McLean, Virginia, USA Copyright © Amari Ice, 2017 Difference Press is a trademark of Becoming Journey, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the author. Reviewers may quote brief passages in reviews. Published 2017 ISBN: 978-1-68309-218-6 DISCLAIMER No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, or transmitted by email without permission in writing from the author. Neither the author nor the publisher assumes any responsibility for errors, omissions, or contrary interpretations of the subject matter herein. Any perceived slight of any individual or organization is purely unintentional. Brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. Cover Design: Jennifer Stimson Editing: Grace Kerina Author photo courtesy of Donta Hensley (photographer), Jay Lautner (editor) 3 To My Love: Thank you for being unapologetically and unwaveringly you, and for being a captive audience for my insatiably playful antics. #IKeep 4 Table of Contents Foreword 6 A Note About the #Hashtags 8 Introduction – Tardy for the Relationship Party 9 Chapter 1 – #OnceUponATime 16 Chapter 2 – What’s Mercury Got to Do with It? 23 Section 1 – Preparing: The Realm of #RelationshipRetrograde 38 Chapter -

Living Clean the Journey Continues

Living Clean The Journey Continues Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Living Clean Approval Draft Copyright © 2011 by Narcotics Anonymous World Services, Inc. All rights reserved World Service Office PO Box 9999 Van Nuys, CA 91409 T 1/818.773.9999 F 1/818.700.0700 www.na.org WSO Catalog Item No. 9146 Living Clean Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One Living Clean .................................................................................................................. 9 NA offers us a path, a process, and a way of life. The work and rewards of recovery are never-ending. We continue to grow and learn no matter where we are on the journey, and more is revealed to us as we go forward. Finding the spark that makes our recovery an ongoing, rewarding, and exciting journey requires active change in our ideas and attitudes. For many of us, this is a shift from desperation to passion. Keys to Freedom ......................................................................................................................... 10 Growing Pains .............................................................................................................................. 12 A Vision of Hope ......................................................................................................................... 15 Desperation to Passion .............................................................................................................. -

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

UFYB 66: Listener Q & a Vol. 12 Full Episode Transcript Kara Loewentheil

UFYB 66: Listener Q & A Vol. 12 Full Episode Transcript With Your Host Kara Loewentheil UnF*ck Your Brain with Kara Loewentheil UFYB 66: Listener Q & A Vol. 12 Welcome to Unf*ck Your Brain, the only podcast that teaches you how to use psychology, feminism, and coaching, to rewire your brain and get what you want in life. And now here's your host, Harvard law school grad, feminist rockstar, and master coach, Kara Loewentheil. Hello my chickens. Today we are answering some more chicken questions. You guys are asking such thought-provoking, interesting, great questions that I just can't stop answering them. Alright, let's just dive in. So here's a question which I get in a lot of different ways, but I'm just going to read this one in particular, but a lot of you have this question so I think it'll be useful. "Dear Kara, I love your podcast, I've been sharing it widely." Thank you. "One question that I'm grappling is how do you reconcile individual responsibility for one's own happiness with systemic oppression? Things like unequal access to healthcare, mass incarceration, the child separation policy, income inequality? While it's true in some sense that everyone is responsible for their own mindset, aren't there things outside an individual's control that influence our wellbeing? And don't we have a collective responsibility to address those things instead of just focusing on ourselves? I feel like I am missing something important." This is a great question and I do think you're missing something important, which is a good sign. -

Queens Park Music Club

Alan Currall BBobob CareyCarey Grieve Grieve Brian Beadie Brian Beadie Clemens Wilhelm CDavidleme Hoylens Wilhelm DDavidavid MichaelHoyle Clarke DGavinavid MaitlandMichael Clarke GDouglasavin M aMorlanditland DEilidhoug lShortas Morland Queens Park Music Club EGayleilidh MiekleShort GHrafnhildurHalldayle Miekle órsdóttir Volume 1 : Kling Klang Jack Wrigley ó ó April 2014 HrafnhildurHalld rsd ttir JJanieack WNicollrigley Jon Burgerman Janie Nicoll Martin Herbert JMauriceon Burg Dohertyerman MMelissaartin H Canbazerbert MMichelleaurice Hannah Doherty MNeileli Clementsssa Canbaz MPennyichel Arcadele Hannah NRobeil ChurmClements PRoben nKennedyy Arcade RobRose Chu Ruanerm RoseStewart Ruane Home RobTom MasonKennedy Vernon and Burns Tom Mason Victoria Morton Stuart Home Vernon and Burns Victoria Morton Martin Herbert The Mic and Me I started publishing criticism in 1996, but I only When you are, as Walter Becker once learned how to write in a way that felt and still sang, on the balls of your ass, you need something feels like my writing in about 2002. There were to lift you and hip hop, for me, was it, even very a lot of contributing factors to this—having been mainstream rap: the vaulting self-confidence, unexpectedly bounced out of a dotcom job that had seesawing beat and herculean handclaps of previously meant I didn’t have to rely on freelancing Eminem’s armour-plated Til I Collapse, for example. for income, leaving London for a slower pace of A song like that says I am going to destroy life on the coast, and reading nonfiction writers everybody else. That’s the braggadocio that hip who taught me about voice and how to arrange hop has always thrived on, but it is laughable for a facts—but one of the main triggers, weirdly enough, critic to want to feel like that: that’s not, officially, was hip hop. -

Educator Guide

EDUCATOR GUIDE The Educator’s Guide is a resource manual for anyone teaching the Choose Love Program in a classroom-based setting. The purpose of this Guide is to provide you with the “need to know” and “nice to know” information that will help you best teach the Choose Love Enrichment Program™. It provides a description of the program, research, content, teaching strategies and best practices for teaching social and emotional learning. ©2019 Jesse Lewis Choose Love Movement CONTENTS The State of Teaching Today ........................................................................................................................................ 4 The Choose Love Movement ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Why the Choose Love Program .................................................................................................................................. 7 Program at a Glance .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Research ............................................................................................... 9 What Is SEL ................................................................................................................................................................... 9 What Skills Does SEL Teach ................................................................................................................................ -

Golden Note Entertainment Inc. Entertainment Checklist

Golden Note Entertainment Inc. Entertainment Checklist Initial Consultation Have a very informative meeting and learn about all of the wonderful services. Sign a contract and book a really awesome Entertainer. Receive organizational material. Go home knowing that you made a wise decision. One Month Prior to Affair Start filling out information in folder and picking out music. Check contract and verify all times and event venue are still the same. Notify entertainer of any changes in contract. Decide if you wish to upgrade or add anything to your package. Prepare a copy of your floor plan, CDs to be given to entertainer, and have the name address and phone number of your photographer and videographer ready for final. Two Weeks Prior to Affair Meet with Entertainer for Final Consultation. MAKE SURE YOU: o Fill out Wedding Sheet – Special Notes – Special Requests. Remember, all information during the final consultation is final. Golden Note does not guarantee to accommodate any changes after the final consultation! Announcements and special notes are easy. We pride ourselves on taking care of almost every request from our client. Doing this takes time. Please make sure that if you have any music changes after the final, that you bring the CD’s to the event with you. o Have a copy of your floor plan. o Have the name, address, and phone number of the photographer and videographer. Pay final balance if any. Day Prior to Affair If paying balance on the day of the affair, be sure it’s prepared in cash, certified check, or money order. -

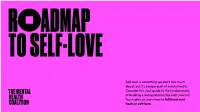

Self-Love Is Something We Don't Talk Much About, but It's a Major Part Of

R ADMAP TO SELF-LOVE Self-love is something we don’t talk much about, but it’s a major part of mental health. Consider this your guide to the fundamentals of building a loving relationship with yourself. You might just learn how to fall head over heels in self-love. What is self-love? Self-love is the practice of caring for your own wellbeing WHAT SELF-LOVE IS WHAT SELF-LOVE IS NOT and happiness. There are many ways to foster self-love, and doing so is important for everyone at every stage of a lifelong process a destination life. Self-love has nothing to do with self-confidence or arrogance – instead, it is appreciation and acceptance of important for everyone self-confidence yourself. To get a sense of what self-love feels like, close your eyes and picture someone you care for very much. part of mental wellness arrogance Notice how you feel. Now, direct those feelings toward yourself – that’s what self-love feels like! maintained with action and effort dependent on what others think of you How do I know that my self-love needs some attention? SELF-LOVE SCALE Some telltale signs that your self-love could use a boost are: feeling depleted, experiencing mental or physical tension, overall decline in mental health, frequent self- critical thoughts, and a tendency to make self-defeating statements. This scale can help you gauge where you are I can’t seem to stop I’ve been mostly I have strong love I fully accept and today so that you can then decide how to strengthen your beating myself up. -

Signature Lattes 12Oz | 16Oz | 24Oz 12Oz | 16Oz | 24Oz | 32Oz 12Oz | 16Oz | 24Oz

(Blended) Hot Iced Mélange Signature Lattes 12oz | 16oz | 24oz 12oz | 16oz | 24oz | 32oz 12oz | 16oz | 24oz Latté 3.15 | 3.85 | 4.65 3.15 | 3.85 | 4.95 | 7.15 3.15 | 3.85 | 4.95 Espresso w/ steamed milk of your choice. Bay Latté 3.75 | 4.50 | 5.25 4.00 | 4.75 | 6.25 | 8.00 4.00 | 4.75 | 6.25 Lavender & organic honey infused latt� in a milk of your choice. Garnished with the essence of real lavender flowers. The FeelLove Latté 3.75 | 4.50 | 5.25 4.00 | 4.75 | 6.25 | 8.00 4.00 | 4.75 | 6.25 Long pull espresso w/ a few inches of perfectly steamed milk of your choice & a touch of honey vanilla. Goddess Latté 3.50 | 4.25 | 4.95 3.50 | 4.25 | 4.95 | 7.50 4.00 | 4.75 | 5.45 A perfect shot of espresso w/ organic steamed milk of your choice & vanilla. FeelLove Muscovado Latté 3.75 | 4.50 | 5.25 3.75 | 4.50 | 5.25 | 7.75 4.25 | 5.00 | 5.75 Muscovado is a mineral-rich sugar that was invented in India 8000 years ago. This latt� includes this special ingredient w/ a molasses swirl atop a perfect layer of foam. Vaughn Gogh Latté 3.75 | 4.5 | 5.25 3.75 | 4.50 | 5.25 | 7.75 4.25 | 5.00 | 5.75 Vanilla honey latt� w/ an artistic caramel swirl atop a perfect layer of foam. Salted Latté 3.50 | 4.25 | 4.95 3.50 | 4.25 | 4.95 | 7.50 4.00 | 4.75 | 5.45 Espresso w/ sweetener & Immortal Mineral Drops in a milk of your choice.