[2020] Fai 34 Inv-B29-20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orkney & Shetland Fly-Drive

Orkney & Shetland Fly-drive Explore the far-flung Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland on this fly-drive adventure Fly north to the distinctive Orkney & Shetland trips to neighbouring islands quite possible. islands and discover Scotland’s Viking and What’s more, we will provide plenty of prehistoric past on this six night fly-drive adventure. suggestions for you. See mysterious stone circles, experience the atmosphere of dwellings from 5,000 years ago We also offer a self-drive holiday as an alternative and simply enjoy the contrasting landscapes, way to visit Orkney & Shetland. seascapes and wildlife. And if time is no problem, extend your stay and The easiest and quickest route to these islands is explore Orkney & Shetland in-depth. by air, and with regular, daily flights taking around ninety minutes from Glasgow or Edinburgh, this is a convenient option to maximise your time in this Days One to Four – Orkney most unique and remote part of the UK. Your holiday begins as you fly from Glasgow or Your hire car on each island group will give you Edinburgh Airport on the 90 or so minute flight to the opportunity to explore during your stay. Orkney. On arrival, collect your hire car and drive The dramatic coastline is never far away, while to your centrally located hotel on the outskirts of causeways and short local ferry crossings make Kirkwall – your base for three nights. 1 [email protected] | 0141 260 9260 | mckinlaykidd.com Your hotel on Orkney Make an early morning or late evening visit to the Ring of Brodgar and standing stones of Stenness – Hidden away somewhat amid the residences on there’s no entrance fee, so you can just wander the outskirts of Kirkwall, your Orkney hotel is an right around and between these mighty stones, inviting and welcoming base. -

The Impact of External Shocks Upon a Peripheral Economy: War and Oil in Twentieth Century Shetland. Barbara Ann Black Thesis

THE IMPACT OF EXTERNAL SHOCKS UPON A PERIPHERAL ECONOMY: WAR AND OIL IN TWENTIETH CENTURY SHETLAND. BARBARA ANN BLACK THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY July 1995 ProQuest Number: 11007964 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007964 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis, within the context of the impact of external shocks on a peripheral economy, offers a soci- economic analysis of the effects of both World Wars and North Sea oil upon Shetland. The assumption is, especially amongst commentators of oil, that the impact of external shocks upon a peripheral economy will be disruptive of equilibrium, setting in motion changes which would otherwise not have occurred. By questioning the classic core-periphery debate, and re-assessing the position of Shetland - an island location labelled 'peripheral' because of the traditional nature of its economic base and distance from the main centres of industrial production - it is possible to challenge this supposition. -

Shetland Islands Visitor Survey 2019 Shetland Islands Council and Visitscotland April 2020 Contents

Shetland Islands Visitor Survey 2019 Shetland Islands Council and VisitScotland April 2020 Contents Project background Trip profile Objectives Visitor experience Method and analysis Volume and value Visitor profile Summary and conclusions Visitor journey 2 Project background • Tourism is one of the most important economic drivers for the Shetland Islands. The islands receive more than 75,000 visits per year from leisure and business visitors. • Shetland Islands Council has developed a strategy for economic development 2018-2022 to ensure that the islands benefit economically from tourism, but in a way that protects its natural, historical and cultural assets, whilst ensuring environmental sustainability, continuous development of high quality tourism products and extending the season. • Strategies to achieve these objectives must be based on sound intelligence about the volume, value and nature of tourism to the islands, as well as a good understanding of how emerging consumer trends are influencing decisions and behaviours, and impacting on visitors’ expectations, perceptions and experiences. • Shetland Islands Council, in partnership with VisitScotland, commissioned research in 2017 to provide robust estimates of visitor volume and value, as well as detailed insight into the experiences, motivations, behaviours and perceptions of visitors to the islands. This research provided a baseline against which future waves could be compared in order to identify trends and monitor the impact of tourism initiatives on the islands. This report details -

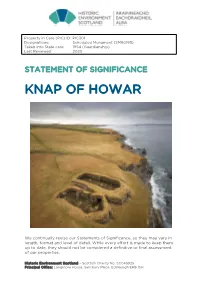

Knap of Howar Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC301 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90195) Taken into State care: 1954 (Guardianship) Last Reviewed: 2020 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KNAP OF HOWAR We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND -

Puffin Bonanza 27Th June to 5Th July 2017 Photographic Tour with Tour Leader Ellie Rothnie

www.natures-images.co.uk Puffin Bonanza 27th June to 5th July 2017 Photographic tour with tour leader Ellie Rothnie Itinerary : Days 1-2 Day 1 there are weight limitations on the plane. The weather conditions in the Shetland Isles are very unpredictable. Tuesday 27th June Sea Fog is our main concern as the planes don’t fly out in these conditions but the ferry does sail and so should We plan to arrive at Sumburgh Airport on Mainland we have difficulties with our flights today we have the Shetland in the afternoon from where it is just a short safety net of getting on the Island via boat the following transfer to our hotel. After dinner, weather and travel morning. Be prepared for a potential boat journey as an tiredness willing, we will stretch our legs and look for alternative should it be necessary. Fair Isle is one of the some first photography at a local arctic tern colony to get remotest inhabited islands in the UK with a population our eye in. of around 60 people. We will be met at the small landing strip and will then transfer to the bird observatory which Day 2 will be our base for the week of puffin photography. After dinner we will head out to the puffin colony for an evening of photography. Wednesday 28th June After breakfast we will set off to Tingwall airport for our island hopping flight to Fair Isle. The plane is only a small Island Hopper and only carries 7 people and we plan to take the morning flight (there are only 2 per day) with any excess luggage following on the second flight because Natures Images | Puffin Bonanza : 27th June to 5th July 2017 Page 1 Itinerary : Days 3-7 Day 3 Days 4 - 7 Thursday 29th June Friday 30th June to Monday 3rd July We have designed this trip to really concentrate on You guessed it the days will follow the same pattern and photographing puffins: we think this is one of the best we will be visiting the various colonies that are dotted colonies in Europe to do so. -

Northern-Lights-Issue-1.Pdf

Issue 1 Northern PLUS Children’s Lights competition INSIDE Orkney and Shetland Golfing in highlights the North of Scotland Lighthouse cover story: Highland Park Fair Isle South Photography competition NorthLink Ferries on board magazine Welcome Contents A warm welcome on board and to Northern Lights Welcome 2 – our new magazine. Travel information - Serco is delighted to operate NorthLink Ferries on behalf of the Scottish on board features Government. These are lifeline ferry services for islanders, ensuring that people to suit you and goods can get to and from the mainland. However, the ferries also provide 3 a gateway for tourists and businesses to access the islands. We aim to provide Meet our Captain you with a comfortable crossing, great services on board and value for money. 6 Since Serco began the operation of NorthLink Ferries in July 2012 we have been Lighthouse feature working hard to refurbish the ships and improve the services that we offer. (cover story) 7 I’m sure you won’t have missed the bold new look of our ferries with the large Orkney and Shetland Viking dominating the side of our ships. Don’t they look fantastic? On board, there is much to experience during your journey – from recliner seats and highlights 8 comfortable sleeping pods to the Viklings Den for play time, a games zone and new menus, with lots of locally sourced produce to choose from. Caithness and Aberdeen highlights For those looking for an exclusive area to relax and dine, our Magnus’ Lounge 10 is the answer. Depending on the service you are sailing with, customers with Highland Park upgraded travel or accommodation can enjoy the benefits of Magnus’ Lounge. -

The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP the Foreign and Commonwealth Office King Charles Street London SW1A 2AH

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 25.4.2018 C(2018) 2400 final PUBLIC VERSION This document is made available for information purposes only. Subject: State Aid SA.49482 (2017/N) – United Kingdom Sumburgh Airport – entrustment of a service of general economic interest Sir, 1. PROCEDURE (1) By letter dated 6 November 2017, the United Kingdom notified to the Commission the entrustment to Sumburgh Airport of a service of general economic interest ("SGEI") by the Scottish government. By letter of 12 December 2017, the Commission requested further information, which was provided by the United Kingdom on 7 February 2018. This decision covers the SGEI entrustment to Sumburgh Aiport during the period 2012-2022. 2. DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF THE MEASURE 2.1. Sumburgh Airport (2) This section summarizes the information and arguments put forward by the United Kingdom in the notification regarding Sumburgh Airport ("Sumburgh Airport" or the "Airport") and the SGEI. (3) Sumburgh Airport is located at the southern end of the Shetland Mainland within the Shetland Islands archipelago in the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom states that it is the only airport within the Shetland Islands to provide scheduled passenger services to destinations outside the Shetland Islands. The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP The Foreign and Commonwealth Office King Charles Street London SW1A 2AH Commission européenne/Europese Commissie, 1049 Bruxelles/Brussel, BELGIQUE/BELGIË - Tel. +32 22991111 (4) The Airport is operated by Highlands and Islands Airports Limited (the "HIAL").1 HIAL was incorporated in Edinburgh on 4 March 1986 under the Companies Act 1985 and is wholly owned by the Scottish government. -

Runway Success

he recent contract for Highland and Islands Airports Ltd (HIAL) to extend and upgrade the Trunway at Sumburgh Airport in the Shetland Islands, the UK’s most northerly gateway, was a notable project for a number of reasons. Not least was that Colas Ltd became the first contractors to successfully utilize European airport surfacing materials within the UK’s airfields industry, coupled with the logistical problems posed by Sumburgh’s remote location, some 150 miles from the Scottish mainland. Working as specialist Runway Success subcontractors to Balfour Beatty Sumburgh Airport in the Shetlands becomes the first UK airfield to benefit Civil Engineering Ltd, as part of an overall £9.75m redevelopment from Colas’s European airport surfacing materials project, Colas undertook the £1.8m resurfacing and grooving of By Carl Fergusson, business manager – Airfields Division, Colas Ltd, and Steve Cant, the existing runway and newly technical manger, Colas Ltd constructed runway extensions. To ensure an efficient, cost-effective programme of physical and mechanical mechanical performance targets works, Colas worked closely with properties of the mix of the Sumburgh laboratory Balfour Beatty and HIAL and, by constituents had to meet French mixture are shown in table 1. drawing on the airport expertise standards. Betoflex provides numerous of their parent company, Colas Unlike typical UK standards, benefits compared with more SA, were able to offer various NF P98-131 does not provide expensive traditional airfield innovative solutions during initial grading or binder content paving materials, not least in project investigations. These specification envelopes. Instead, terms of whole-life cost, and can included sourcing the required mechanical performance targets be manufactured and laid more aggregate from a temporary for laboratory mixtures are quickly, which meant some 200 quarry (Wilsness Hill) inside the linear metres of runway could be defined and end-product airfield perimeter and using their laid each night at Sumburgh. -

Protected Radar List Updated 05 January 2021

Protected Radar list Updated 05 January 2021 List of military and civil radars to be protected Coordination with aeronautical radionavigation in the 2.7 GHz radar band. List of civil and military radars to be protected are listed in the tables below. The area where the radar is protected is limited by the current position and within the airfield boundary1. All sites have been remediated. Jan 2021 update: higher resolution location added for Leeds Bradford Airport 1 The CAA has records of airfield boundaries as part of its aerodrome licensing, available at http://www.caa.co.uk/Commercial-industry/Airports/Aerodrome-licences/Licences/Aerodrome-licences-and- boundary-maps/ MOD airfield boundary maps are available at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/manage-your-licence/radiocommunication- licences/mobile-wireless-broadband/mod-maps Antenna Name Latitude Longitude Height Location Post Code (m agl) Civil radars Allanshill radar station 57N3835 002W1000 12.5m Postcode nearest AB43 7LS to the site Belfast City Airport 54N3658 005W5251 4.5m Sydenham by-Pass BT3 9JH Belfast Belfast International 54N3921 006W1222 17m Belfast BT29 4AB Birmingham 52N2700 001W4500 17.49m Diamond House B26 3QJ International Airport Birmingham Bournemouth 50N4659 001W5035 20m Hurn, Christchurch BH23 6SE International Airport Dorset Bristol Airport 51N2300 02W4300 20m Control Tower Building BS48 3DY Bristol Cambridge Airport 52N1200 000E1100 13.1m Newmarket Road CB5 8RX Cambridge Cardiff International 51N2341 003W2112 17m Rhoose, Barry CF62 3BD Airport South Glamorgan Coventry -

OUR AIRPORTS LOCAL ACCESS – GLOBAL OUTLOOK Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2010/11

OUR AIRPORTS LOCAL ACCESS – GLOBAL OUTLOOK Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2010/11 SG/2011/146 1 CONTENTS 2 WHO WE ARE 12 DUNDEE 4 ANNUAL TRAFFIC 13 INVERNESS STATISTICS 14 KIRKWALL 5 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 15 STORNOWAY 6 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 16 SUMBURGH 8 MANAGING DIRECTOR’S 17 WICK STATEMENT 18 OUR GROUP FINANCIAL 10 YOUR AIRPORTS STATEMENTS BARRA, BENBECULA XX TARGETS FOR 11 CAMPBELTOWN, DEVELOPMENT ISLAY & TIREE & PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 2 3 Our core activities are: Supporting Scotland’s HIAL was incorporated in Edinburgh WHO WE ARE • Providing airports which meet regulatory sustainable development on 4 March 1986 as a private limited company. On 1 April 1995, ownership standards and support essential We work closely with our customers and of the company transferred from the UK transport connectivity. Highlands and Islands Airports Ltd (HIAL) is stakeholders to ensure that our strategic Civil Aviation Authority to the Secretary a private limited company wholly owned by • Maintaining and developing airport goals support sustainable development of State for Scotland and subsequently infrastructure and services. within the communities we serve and to the Scottish Ministers. Scottish Ministers and is responsible for the are aligned with the policy objectives HIAL receives subsidies from the management and operation of 11 airports. • Working with airlines and stakeholders of the Scottish Government. to maintain and develop scheduled, Scottish Government in accordance with Section 34 of the Civil Aviation charter and freight air services. Wealthier and Fairer – our airports Our airports are located at: Barra; provide access to air transport Act 1982 and is sponsored by the Benbecula; Campbeltown; Dundee; Our mission: connections which support sustainable Transport Scotland - Aviation, Maritime, Frieght and Canals Sumburgh: Inverness; Islay; Kirkwall; Stornoway; To provide and operate safe, secure economic growth and social inclusion. -

1 Minutes of the Dundee Airport Ltd (“Dal”) Board

MINUTES OF THE DUNDEE AIRPORT LTD (“DAL”) BOARD HELD AT SUMBURGH AIRPORT ON TUESDAY 19TH MARCH 2019 AT 15:00 Board Attendees: Lorna Jack (Chair) LJ Inglis Lyon (Managing Director) IL Gillian Bruton (Finance Director) Jim McLaughlin (Non-Executive Director) JM David Savile (Non-Executive Director) DS Tim Whittome (Non-Executive Director) TW In Attendance: Mark Stuart (Director of Airport Operations) MS Denise Sutherland (Head of Communications) DSu Gary Cox (Transport Scotland) GC Shelly Donaldson (Personal Assistant – Minutes) Via Phone: David Martin (Dundee City Council) DM Gregor Hamilton (Dundee City Council) GH The DAL Board Meeting Commenced at 15:00 Apologies were received from Mr Macrae. Declarations of Interest No declarations of interest were noted. Item 1 - Matters Arising Chair’s Report LJ reported that the public appointments process to recruit the non-executive director vacancy on the Board had begun. The proposal was to include recruitment of the two vacancies that would arise in March 2020, given the timescale for these processes. LJ advised she had met with Caithness Chamber of Commerce and the Caithness MSP regarding the operating hours for Wick airport. Together with IL and the Head of HR, LJ met MSP’s at the Parliament building to provide an update on the Air Traffic Controllers (ATC) Pay dispute. LJ wished to note the Decreasing Margins workshop held in February was a success. Managing Director’s Report IL reported that work continues on balancing HIAL’s revenue budget. 1 IL informed the Board that calls have been arranged with local authorities and that HIAL is continuing to keep stakeholders informed of developments in relation to the ATC Pay dispute and proposed industrial action. -

An Automation Anomaly Software Did Not Block Erroneous Acceleration Data

ONRecorD An Automation Anomaly Software did not block erroneous acceleration data. BY MARK LACAGNINA The following information provides an aware- moving the thrust levers to the idle position,” ness of problems in the hope that they can be the report said. Nevertheless, the aircraft pitched avoided in the future. The information is based nose-up again and climbed 2,000 ft. on final reports on aircraft accidents and inci- “The flight crew notified air traffic control dents by official investigative authorities. (ATC) that they could not maintain altitude and requested a descent and radar assistance for a JETS return to Perth,” the report said. “The crew were able to verify the actual aircraft groundspeed Crew Had No Guidance for Response and altitude with ATC.” Boeing 777-200. No damage. No injuries. PFD indications appeared normal during he aircraft was climbing through Flight Level the descent. The PIC engaged the left autopilot (FL) 380, about 38,000 ft, after departing from but then disengaged it when the aircraft pitched TPerth, Western Australia, for a scheduled flight nose-down and banked right. “A similar result to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the evening of Aug. occurred when the right autopilot was selected, 1, 2005, when the flight crew observed a “LOW so the PIC left the autopilot disengaged and AIRSPEED” advisory on the engine indicating manually flew the aircraft,” the report said. and crew alerting system (EICAS). At the same The PIC was unable to disengage the auto- time, the primary flight display (PFD) showed a throttle system with the disconnect switches on full-right slip/skid indication, said the Australian the thrust levers or the disconnect switch on Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) report.