Navigating Youth Media Landscapes: Challenges and Opportunities for Public Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 123 2nd International Conference on Education, Sports, Arts and Management Engineering (ICESAME 2017) The Application of New Media Technology in the Ideological and Political Education of College Students Hao Lu 1, a 1 Jiangxi Vocational & Technical College of Information Application, Nanchang, China [email protected] Keywords: new media; application; the Ideological and Political Education Abstract: With the development of science and technology, new media technology has been more widely used in teaching. In particular, the impact of new media technology on college students’ ideological and political education is very important. The development of new media technology has brought the opportunities to college students’ ideological and political education while bringing the challenges. Therefore, it is an urgent task to study on college students’ ideological and political education under the new media environment. 1. Introduction New media technology, relative to traditional media technology, is the emerging electronic media technology on the basis of digital technology, internet technology, mobile communication technology, etc. it mainly contains fetion, wechat, blog, podcast, network television, network radio, online games, digital TV, virtual communities, portals, search engines, etc. With the rapid development and wide application of science and technology, new media technology has profoundly affected students’ learning and life. Of course, it also brings new challenges and opportunities to college students’ ideological and political education. Therefore, how to better use the new media technology to improve college students’ ideological and political education becomes the problems needing to be solving by college moral educators. 2. The intervention mode and its characteristics of new media technology New media technology, including blog, instant messaging tools, streaming media, etc, is a new network tools and application mode and instant messaging carriers under the network environment. -

Audience Affect, Interactivity, and Genre in the Age of Streaming TV

. Volume 16, Issue 2 November 2019 Navigating the Nebula: Audience affect, interactivity, and genre in the age of streaming TV James M. Elrod, University of Michigan, USA Abstract: Streaming technologies continue to shift audience viewing practices. However, aside from addressing how these developments allow for more complex serialized streaming television, not much work has approached concerns of specific genres that fall under the field of digital streaming. How do emergent and encouraged modes of viewing across various SVOD platforms re-shape how audiences affectively experience and interact with genre and generic texts? What happens to collective audience discourses as the majority of viewers’ situated consumption of new serial content becomes increasingly accelerated, adaptable, and individualized? Given the range and diversity of genres and fandoms, which often intersect and overlap despite their current fragmentation across geographies, platforms, and lines of access, why might it be pertinent to reconfigure genre itself as a site or node of affective experience and interactive, collective production? Finally, as studies of streaming television advance within the industry and academia, how might we ponder on a genre-by- genre basis, fandoms’ potential need for time and space to collectively process and interact affectively with generic serial texts – in other words, to consider genres and generic texts themselves as key mediative sites between the contexts of production and those of fans’ interactivity and communal, affective pleasure? This article draws together threads of commentary from the industry, scholars, and culture writers about SVOD platforms, emergent viewing practices, speculative genres, and fandoms to argue for the centrality of genre in interventions into audience studies. -

Streaming Media Seminar – Effective Development and Distribution Of

Proceedings of the 2004 ASCUE Conference, www.ascue.org June 6 – 10, 1004, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina Streaming Media Seminar – Effective Development and Distribution of Streaming Multimedia in Education Robert Mainhart Electronic Classroom/Video Production Manager James Gerraughty Production Coordinator Kristine M. Anderson Distributed Learning Course Management Specialist CERMUSA - Saint Francis University P.O. Box 600 Loretto, PA 15940-0600 814-472-3947 [email protected] This project is partially supported by the Center of Excellence for Remote and Medically Under- Served Areas (CERMUSA) at Saint Francis University, Loretto, Pennsylvania, under the Office of Naval Research Grant Number N000140210938. Introduction Concisely defined, “streaming media” is moving video and/or audio transmitted over the Internet for immediate viewing/listening by an end user. However, at Saint Francis University’s Center of Excellence for Remote and Medically Under-Served Areas (CERMUSA), we approach stream- ing media from a broader perspective. Our working definition includes a wide range of visual electronic multimedia that can be transmitted across the Internet for viewing in real time or saved as a file for later viewing. While downloading and saving a media file for later play is not, strictly speaking, a form of streaming, we include that method in our discussion of multimedia content used in education. There are numerous media types and within most, multiple hardware and software platforms used to develop and distribute video and audio content across campus or the Internet. Faster, less expensive and more powerful computers and related tools brings the possibility of content crea- tion, editing and distribution into the hands of the content creators. -

Streaming Media for Web Based Training

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 448 705 IR 020 468 AUTHOR Childers, Chad; Rizzo, Frank; Bangert, Linda TITLE Streaming Media for Web Based Training. PUB DATE 1999-10-00 NOTE 7p.; In: WebNet 99 World Conference on the WWW and Internet Proceedings (Honolulu, Hawaii, October 24-30, 1999); see IR 020 454. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Computer Uses in Education; Educational Technology; *Instructional Design; *Material Development; *Multimedia Instruction; *Multimedia Materials; Standards; *Training; World Wide Web IDENTIFIERS Streaming Audio; Streaming Video; Technology Utilization; *Web Based Instruction ABSTRACT This paper discusses streaming media for World Wide Web-based training (WBT). The first section addresses WBT in the 21st century, including the Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language (SMIL) standard that allows multimedia content such as text, pictures, sound, and video to be synchronized for a coherent learning experience. The second section covers definitions, history, and current status. The third section presents SMIL as the best direction for WBT. The fourth section describes building a WBT module,using SMIL, including interface design, learning materials content design, and building the RealText[TM], RealPix[TM], and SMIL files. The fifth section addresses technological issues, including encoding content to RealNetworks formats, uploading files to stream server, and hardware requirements. The final section summarizes future directions. (MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS CENTER (ERIC) BEEN GRANTED BY fH This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization G.H. -

Fundamentals of Streaming Media Systems

Chapter 1 FUNDAMENTALS OF STREAMING MEDIA SYSTEMS Multimedia (MM) systems utilize audio and visual information, such as video, audio, text, graphics, still images, and animations to provide effec- tive means for communication. These systems utilize multi-human senses in conveying information, and they play a major role in educational ap- plications (such as e-learning and distance learning), library information systems (such as digital library systems), entertainment systems (such as Video-On-Demand and interactive TV), communication systems (such as mobile phone multimedia messaging), military systems (such as Advanced Leadership Training Simulation), etc. Due to the exponential improvements of the past few years in solid state technology (i.e., processor and memory) as well as increased bandwidth and storage capacities of modern magnetic disk drives, it has been technically feasible to implement these systems in ways we only could have dreamed about a decade ago. Achallenging task when implementing MM systems is to support the sustained bandwidth required to display Streaming Media (SM) objects, such as video and audio objects. Unlike traditional data types, such as records, text and still images, SM objects are usually large in size. For example, a two- hour MPEG-2 encoded movie requires approximately 3.6 gigabytes (GByte) of storage (at a display rate of 4 megabits per second (Mb/s)). Figure 1.1 compares the space requirements for ninety minute video clips encoded in different industry standard digital formats. Second, the isochronous nature of SM objects requires timely, real-time display of data blocks at a pre- specified rate. For example, the NTSC video standard requires that 30 video frames per second be displayed to a viewer. -

Who to See @ IBC

sponsored content Streaming Media magazine’s Who to See @ IBC IF YOU ARE HEADING TO IBC and Flyover Pods looking to find top companies specialising in online video products and services, look no further. Here’s this year’s list of our sponsors that have an exhibition presence amongst the sea of over 1,700 companies fighting for attention. Streaming Media magazine will once again be at IBC this year. Visit us in the newly-created flyover walkway between Halls 7 and 8. We are located in Pod MP3, so stop by to say hello, chat with us about Streaming Media magazine, and pick up information on our upcoming conferences: Streaming Media West and Live Streaming Summit, which will be held in Los Angeles, Calif., at the Westin Bonaventure, 19–20 Nov. You can also visit our website at StreamingMedia.com/Conferences/West2019 to get the latest information about speakers, sessions, and exhibitors. If you’d like to meet with us, please don’t hesitate to email us at [email protected]. Archiware is a manufacturer of high quality, easy to use data management software, based in Munich, Germany. Focussing on the M&E industry, Archiware’s P5 Axinom is a digital solutions provider in the media and software suite includes modules for Archive, entertainment industry, serving the industry with scalable and robust products for content management, Backup and Cloning. P5 is compatible with virtually and protection. Our products power the biggest media, any LTO Tape and Disk storage, several Cloud providers broadcast, and telecommunications organizations in and numerous Media Asset Management products. -

Reliable Streaming Media Delivery

WHITE PAPER Reliable Streaming Media Delivery www.ixiacom.com 915-1777-01 Rev B January 2014 2 Table of Contents Overview ................................................................................................................ 4 Business Trends ..................................................................................................... 6 Technology Trends ................................................................................................. 7 Building in Reliability .............................................................................................. 8 Ixia’s Test Solutions ............................................................................................... 9 Streaming Media Test Scenarios ........................................................................... 11 Conclusion .............................................................................................................13 3 Overview Streaming media is an evolving set of technologies that deliver multimedia content over the Internet and private networks. A number of service businesses are dedicated to streaming media delivery, including YouTube, Brightcove, Vimeo, Metacafe, BBC iPlayer, and Hulu. Streaming video delivery is growing dramatically: according to the comScore Video Metrix1, Americans viewed a significantly higher number of videos in 2009 than in 2008 (up 19%) due to both increased content consumption and the growing number of video ads delivered. In January of 2010, more than 170 million viewers watched videos -

Protection and Restriction to the Internet

Protection and restriction to the internet Dear wireless users, To allow all our users to enjoy quality browsing experience, our firewall has been configured to filter websites/applications to safeguards the interests of our student community in ensuring uninterrupted access to the Internet for academic purposes. In the process of doing this, the firewall will block access to the applications listed in the table below during peak hours ( Weekdays: 8:30am to 5pm ) which: o may potentially pose security hazards o result in excessive use of bandwidth, thereby reducing access to online and educational resources by the larger student community o could potentially result in violation of Malaysian Laws relating to improper and illegal use of the Internet Nevertheless, you may access the restricted websites/applications if they do not potentially pose any security hazards or violation of Malaysian law from our lab computers during our operation hours (Weekdays: 8:30am – 9:30pm) or you may access via the wireless@ucti or wireless@APU network from your mobile devices after the peak hours. Internet services provided by the University should mainly be used for collaborative, educational and research purposes in support of academic activities carried out by students and staff. However, if there are certain web services which are essential to students' learning, please approach Technology Services to discuss how access could be granted by emailing to [email protected] from your university email with the following details: • Restricted website/application -

Delivering Live and On-Demand Smooth Streaming

Delivering Live and On-Demand Smooth Streaming Video delivered over the Internet has become an increasingly important element of the online presence of many companies. Organizations depend on Internet video for everything from corporate training and product launch webcasts, to more complex streamed content such as live televised sports events. No matter what the scale, to be successful an online video program requires a carefully-planned workflow that employs the right technology and tools, network architecture, and event management. This deployment guide was developed by capturing real world experiences from iStreamPlanet® and its use of the Microsoft® platform technologies, including Microsoft® SilverlightTM and Internet Information Services (IIS) Smooth Streaming, that have powered several successful online video events. This document aims to deliver an introductory view of the considerations for acquiring, creating, delivering, and managing live and on-demand SD and HD video. This guide will touch on a wide range of new tools and technologies which are emerging and essential components to deployed solutions, including applications and tools for live and on- demand encoding, delivery, content management (CMS) and Digital Asset Management (DAM) editing, data synchronization, and advertisement management. P1 | Delivering Live and On-Demand Streaming Media A Step-by-Step Development Process This paper was developed to be a hands-on, practical 1. Production document to provide guidance, best practices, and 2. Content Acquisition resources throughout every step of the video production 3. Encoding and delivery workflow. When delivering a live event over 4. Content Delivery the Internet, content owners need to address six key 5. Playback Experience areas, shown in Figure 1: 6. -

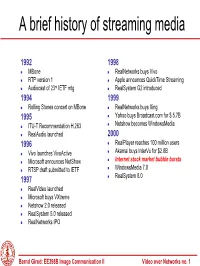

A Brief History of Streaming Media

A brief history of streaming media 1992 1998 MBone RealNetworks buys Vivo RTP version 1 Apple announces QuickTime Streaming rd Audiocast of 23 IETF mtg RealSystem G2 introduced 1994 1999 Rolling Stones concert on MBone RealNetworks buys Xing 1995 Yahoo buys Broadcast.com for $ 5.7B Netshow becomes WindowsMedia ITU-T Recommendation H.263 RealAudio launched 2000 1996 RealPlayer reaches 100 million users Akamai buys InterVu for $2.8B Vivo launches VivoActive Internet stock market bubble bursts Microsoft announces NetShow WindowsMedia 7.0 RTSP draft submitted to IETF 1997 RealSystem 8.0 RealVideo launched Microsoft buys VXtreme Netshow 2.0 released RealSystem 5.0 released RealNetworks IPO Bernd Girod: EE398B Image Communication II Video over Networks no. 1 Desktop Computer CPU Power CPU Power SPECint92 2000 CIF MPEG 1 decoder 200 QCIF H.320/H.324 codec Intel Pentium 20 Motorola PowerPC MIPS R4400 DEC Alpha 2 Intel 486DX2/66 1980 1990 2000 Year [Girod 94] Bernd Girod: EE398B Image Communication II Video over Networks no. 2 Internet Media Streaming Streaming client Media Server DSL Internet 56K modem wireless Best-effort network ChallengesChallenges • low bit-rate ••compressioncompression • variable throughput ••raterate scalability scalability • variable loss ••errorerror resiliency resiliency • variable delay ••lowlow latency latency Bernd Girod: EE398B Image Communication II Video over Networks no. 3 On-demand vs. live streaming Client 1000s simultaneous Media Server streams DSL Internet 56K modem wireless „Producer“ Bernd Girod: EE398B Image Communication II Video over Networks no. 4 Live streaming to large audiences „Producer“ Content-delivery network Relay servers . “Pseudo-multicasting” by stream replication Bernd Girod: EE398B Image Communication II Video over Networks no. -

Local Value 2018 Key Services Local Impact

“SDPB makes a difference in the lives our state’s citizens every day. It’s a shining example of how public/private partnerships should work.” – Matt Michels, former SD Lieutenant Governor 2018 Local Content & Service Report to the Community LOCAL 2018 KEY LOCAL VALUE SERVICES IMPACT The only statewide multi-platform Statewide Television, Radio, Digital Statewide source of information from media resource owned in-state. & Educational platforms, including 9 state officials and local experts for vital television transmitters and 6 television news and information. South Dakota’s statewide source for translators; and 11 radio transmitters Provides South Dakota communities comprehensive High School and nine radio translators. local coverage & civic engagement with Achievement coverage with 100+ coverage of high school events. events broadcast and profiled across all Comprehensive coverage via TV, Radio & Digital of South Dakota people, SDPB.org has 811,624 active web platforms. users and 4,550,417 page views. places, culture, arts & issues. State’s most accessible and Over 102,600 photos available on extensive resource for South Dakota Multi-platform resource on local & Flickr with 45.5+ million lifetime views. State Legislature, including live feeds, state office candidates & ballot issues 2,600+ educators/parents subscribe reports and broadcasts direct from the for South Dakota voters. to SDPB’s Education Update Capitol. e-newsletter & 3,800+ educators & More than 200 hours of multi- parents to SDPB/PBS LearningMedia platform State Legislative coverage. State’s only source for local, in-depth service. documentary and history programming Complete, accessible, digitized More than 17,000 subscribers for about South Dakota. SDPB e-newsletters and SDPB archives of programming. -

FISHING for LEARNING with a PODCAST NET by JACE HARGIS* KATHLEEN SCHOFIELD** DAVID WILSON***

ARTICLES FISHING FOR LEARNING WITH A PODCAST NET By JACE HARGIS* KATHLEEN SCHOFIELD** DAVID WILSON*** ABSTRACT Communicating through the internet has quickly evolved from email, listservs, discussion boards, instant messaging, blogging and now to podcasting. Many of these communication tools have been exploited by the educational community and the latter appears to be no exception. This paper will share background on blogs and podcasts as well as real-world samples, academic examples and a plan to use podcasts as a teaching and learning tool. Keywords: Podcast, Listserv, Blog, Weblog, Instructional Technology, Podcasting in Education. INTRODUCTION for work. Some are for both. Blogs are also excellent Using technology in a relevant, useful way has been team/department/company/family communication feasible only for some people, at particular times and in tools. They help small groups to communicate in a way certain situations. Others have found technology to be that is simpler and easier to follow than emails or somewhat less useful, cumbersome and a nuisance. The discussion forums. A blog can help to keep everyone in search for the elusive Utopian myth of technology for the loop, promote cohesiveness and create a everyone, at any time, has been recognized by many. community culture. Although blogs are relatively new, a However, the search for additional tools that cater to the significant amount of literature has already been uniqueness of various teaching and learning styles gathered. remains active. The web logging or blog phenomenon Blood (2000) summarises web Blogs as, A History and was welcomed by many technophiles as well as those in Perspective at http://www.rebeccablood.net/ academia, producing various academic blogs.