Resource Assessment2 Bucks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mulberry Cottage, High Street, Shutlanger £565,000 Freehold

A Substantial Stone Cottage 24ft x 17ft Sitting Room, Family Room Shaker Style Fitted Kitchen Four Bedrooms, Re-fitted Bathroom Master & Guest Bedroom En-Suites Study/Music Room, Four Car Garage Suitable for Conversion, S.T.P. Pretty South Facing Rear Garden EPC Energy Rating - G Mulberry Cottage, High Street, Shutlanger £565,000 Freehold Mulberry Cottage, 16b High Street, Shutlanger, Northants. NN12 7RP Mulberry Cottage a substantial four bedroom LOCATION: Shutlanger is situated 4 miles from Towcester, midway between the semi-detached stone cottage standing in the A5 and A508 both giving excellent access Northampton or Milton Keynes where there is a main-line Intercity train service to London Euston (40 minutes). The heart of this sought after village. Improved by the A508 also gives access north to junction 15 of the M1 and there is easy access to the southwest of Towcester and Brackley. Shutlanger has its own Parish Council present owners, the property offers many and belongs to the church grouping with Stoke Bruerne and Grafton Regis. The original features complemented by a modern village has a pub with an excellent reputation for real ale and food (The Plough) and a village hall. The nearest primary school and Church are at Stoke Bruerne fitted kitchen, the master en-suite with a roll top one mile east of Shutlanger. slipper bath, a guest en-suite shower room and family bathroom. In addition an Edwardian style conservatory has been added at the rear taking full advantage of the south facing garden. The spacious sitting room features a stone fireplace with a multi-fuel stove and the family/dining room retains an inglenook fireplace with an exposed bressumer beam. -

The Grange ALDERTON TURN • GRAFTON REGIS • TOWCESTER • NORTHAMPTONSHIRE

The Grange ALDERTON TURN • GRAFTON REGIS • TOWCESTER • NORTHAMPTONSHIRE The Grange ALDERTON TURN • GRAFTON REGIS • TOWCESTER NORTHAMPTONSHIRE A substantial family home occupying an elevated position with beautiful views over rolling countryside, standing in 18 acres Milton Keynes 9 miles (train to Birmingham New Street from 55 minutes and to London from 35 minutes), Towcester 7 miles Stony Stratford 4 miles, Northampton 10.5 miles • M1 (J15) 6.6 miles, A5 2.8 miles Wolverton Railway Station 4 miles (trains to London Euston from 40 minutes) (Distances and times approximate) Accommodation & Amenities Reception hall Drawing room Sitting room Dining room Kitchen/breakfast room Utility Shower room and cloakroom Master bedroom with en suite • 3 Further double bedrooms Family bathroom Double garage Range of outbuildings totalling 54,000 square feet In all about 7.28 hectares (18 acres) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. Situation • Situated within a small and picturesque Conservation Village within this lovely rural setting to the south of Towcester • The village which is mentioned in the Domesday book has the site, the mount, the site of a medieval motte and bailey castle and church • The Grange benefits from a central location North East of Milton Keynes offering good access to the A5 and M1 • Nearby Milton Keynes offers a large commercial centre with fashionable businesses and a state of the art shopping centre • The traditional market towns of Towcester and Stony Stratford offer independent shops, galleries, bars and restaurants as well as supermarkets • Being a short distance from Wolverton Railway Station which provides many fast connections including Milton Keynes within 3 minutes and London Euston within 40 minutes. -

The Hidation of Buckinghamshire. Keith Bailey

THE HIDA TION OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE KEITH BAILEY In a pioneering paper Mr Bailey here subjects the Domesday data on the hidation of Buckinghamshire to a searching statistical analysis, using techniques never before applied to this county. His aim is not explain the hide, but to lay a foundation on which an explanation may be built; to isolate what is truly exceptional and therefore calls for further study. Although he disclaims any intention of going beyond analysis, his paper will surely advance our understanding of a very important feature of early English society. Part 1: Domesday Book 'What was the hide?' F. W. Maitland, in posing purposes for which it may be asked shows just 'this dreary old question' in his seminal study of how difficult it is to reach a consensus. It is Domesday Book,1 was right in saying that it almost, one might say, a Holy Grail, and sub• is in fact central to many of the great questions ject to many interpretations designed to fit this of early English history. He was echoed by or that theory about Anglo-Saxon society, its Baring a few years later, who wrote, 'the hide is origins and structures. grown somewhat tiresome, but we cannot well neglect it, for on no other Saxon institution In view of the large number of scholars who have we so many details, if we can but decipher have contributed to the subject, further discus• 2 them'. Many subsequent scholars have also sion might appear redundant. So it would be directed their attention to this subject: A. -

Northampton Map & Guide

northampton A-Z bus services in northampton to Brixworth, to Scaldwell Moulton to Kettering College T Abington H5 Northampton Town Centre F6 service monday to saturday monday to saturday sunday public transport in Market Harborough h e number operator route description daytime evening daytime and Leicester Abington Vale I5 Obelisk Rise F1 19 G to Sywell r 19.58 o 58 v and Kettering Bellinge L4 1 Stagecoach Town Centre – Blackthorn/Rectory Farm 10 mins 30 mins 20 mins e Overstone Lodge K2 0 1/4 1/2 Mile 62 X10 7A.10 Blackthorn K2 Parklands G2 (+ evenings hourly) northampton X10 8 0 1/2 1 Kilometre Boothville I2 0 7A.10 Pineham B8 1 Stagecoach Wootton Fields - General Hospital - Town Centre – peak-time hourly No Service No Service 5 from 4 June 2017 A H7 tree X10 X10 Brackmills t S t es Blackthorn/Rectory Farm off peak 30 mins W ch Queens Park F4 r h 10 X10 10 t r to Mears Ashby Briar Hill D7 Street o Chu oad Rectory Farm L2 core bus services other bus services N one Road R 2 Stagecoach Camp Hill - Town Centre - 15 mins Early evening only 30 mins verst O ll A e Bridleways L2 w (for full route details see frequency guide right) (for full route details see frequency guide right) s y d S h w a Riverside J5 Blackthorn/Rectory Farm le e o i y Camp Hill D7 V 77 R L d k a Moulton 1 o a r ue Round Spinney J1 X7 X7 h R 62 n a en Cliftonville G6 3 Stagecoach Town Centre – Harlestone Manor 5 to 6 journeys each way No Service No Service route 1 Other daily services g e P Av u n to 58 e o h Th Rye Hill C4 2 r Boughton ug 19 1 Collingtree F11 off peak 62 o route 2 Bo Other infrequent services b 7A r 5 a Crow Lane L4 Semilong F5 e Overstone H 10 3 Stagecoach Northampton – Hackleton hourly No Service No Service route 5 [X4] n Evenings / Sundays only a Park D5 D6 d Dallington Sixfields 7/7A 62 L 19 a Mo ulto routes 7/7A o n L 5 Stagecoach St. -

1948 Marsh Gibbon Parish Council Minutes of The

MARSH GIBBON PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON TUESDAY 14 JANUARY 2020 PRESENT: Cllrs A Lambourne (Chair), P Evershed (PE), D Leonard (DL), R Cross (RC) and J Smith (JS) In attendance: DC Angela Macpherson, 1 member of the public and C Jackman (Clerk) The meeting commenced at 7.30pm. 1. APOLOGIES Cllr I Metherell (IM) and Cllr E Taylor (ET). 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest. 3. MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON 10 DECEMBER 2019 The Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on 10 December 2019 were agreed by those present and signed by the Chairman. 4. MATTERS ARISING There were no matters arising. 5. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION Chair welcomed the member of the public. 6. GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE The following items had been circulated via email and dealt with where indicated: AVDC From Subject Action i 30 Dec Finance Ack: 2020/21 Parish Tax Base Information and request for Noted Parish Precept ii 20 Dec Planning Planning Application Consultation 19/04427/ALB Minute 7 iii 10 Jan Parish Liaison Officer AVDC Licencing - Small Society Lottery To Councillors iv 10 Jan Parish Liaison Officer Severe weather emergency provision (SWEP) accommodation To Councillors BCC From Subject Action i 19 Dec Permit Officer TTRO - Cheddington Road, Mentmore To Councillors ii 19 Dec Permit Officer TTRO - Main Street, Maids Moreton To Councillors iii 19 Dec Permit Officer TTRO - St Johns Street, Aylesbury To Councillors iv 19 Dec Permit Officer TTRO - Hale Lane, Wendover To Councillors v 17 Dec HS2 HS2 - A413 Wendover Bypass To Councillors vi 17 Dec Permit Officer TTRO Avenue Road, Winslow To Councillors vii 16 Dec Permit Officer TTRO - Church Lane, Aston Clinton Noted viii 16 Dec HS2 HS2 - Wendover Bypass To Councillors ix 13 Dec LAT TfB Flooding - Marsh Gibbon OX27 0EY Minute 11 x 7 Jan Permit Officer TTRO - Silverstone British Grand Prix – 2020 Noted xi 7 Jan Permit Officer TTRO - TTRO - High Street, Wing Noted xii. -

Late Medieval Buckinghamshire

SOLENT THAMES HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT MEDIEVAL BUCKINGHAMSHIRE (AD 1066 - 1540) Kim Taylor-Moore with contributions by Chris Dyer July 2007 1. Inheritance Domesday Book shows that by 1086 the social and economic frameworks that underlay much of medieval England were already largely in place. The great Anglo Saxon estates had fragmented into the more compact units of the manorial system and smaller parishes had probably formed out of the large parochia of the minster churches. The Norman Conquest had resulted in the almost complete replacement of the Anglo Saxon aristocracy with one of Norman origin but the social structure remained that of an aristocratic elite supported by the labours of the peasantry. Open-field farming, and probably the nucleated villages usually associated with it, had become the norm over large parts of the country, including much of the northern part of Buckinghamshire, the most heavily populated part of the county. The Chilterns and the south of the county remained for the most part areas of dispersed settlement. The county of Buckinghamshire seems to have been an entirely artificial creation with its borders reflecting no known earlier tribal or political boundaries. It had come into existence by the beginning of the eleventh century when it was defined as the area providing support to the burh at Buckingham, one of a chain of such burhs built to defend Wessex from Viking attack (Blair 1994, 102-5). Buckingham lay in the far north of the newly created county and the disadvantages associated with this position quickly became apparent as its strategic importance declined. -

Aylesbury and Return from Gayton | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Aylesbury and return from Gayton Cruise this route from : Gayton View the latest version of this pdf Aylesbury-and-return-from-Gayton-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 8.00 to 0.00 Cruising Time : 46.00 Total Distance : 88.00 Number of Locks : 82 Number of Tunnels : 2 Number of Aqueducts : 2 Aylesbury is a busy market town with a number of attractive squares in its centre. The Buckinghamshire County museum is here, which also houses the Roald Dahl Gallery. Milton Keynes has a lot to offer , it is one of the major shopping areas around this area, and is great for the more adventurous You can toboggan on real snow in The Toboggan Zone, and go indoor skydiving. Blisworth Tunnel, at 3057 yards is the 3rd longest tunnel open to navigation in the UK Cross the stunning Iron Trunk Aqueduct - a must for a photo opportunity. It's a magnificent Georgian structure, which carries the Grand Union Canal over the River Ouse. Built in 1811 by canal engineer Benjamin Beavan, the aqueduct stands at an impressive 10.8 metres high and connects Wolverton with Cosgrove. Stoke Bruerne is perhaps the best example of a canal village in the country, and the Blisworth stone built houses flank the canal. The warehouses and cottages along the wharf have become a canal centre. Great Linford is a lovely village built in the traditional golden stone, it is a magnificent canal village with church, manor, farm and almshouses close to the canal Cruising Notes Day 1 From Gayton Marina turn right back onto the Northampton Arm of the Grand Union Canal, then left towards Aylesbury at Gayton Junction. -

LENT GROUPS Will Happen As Follows

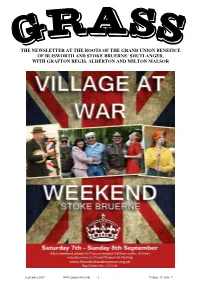

THE NEWSLETTER AT THE ROOTS OF THE GRAND UNION BENEFICE OF BLISWORTH AND STOKE BRUERNE/ SHUTLANGER, WITH GRAFTON REGIS, ALDERTON AND MILTON MALSOR September 2019 www.grassnews.co.uk - 1 - Volume 39, Issue 9 Pastoral Letter Dear All, I come to you all with a theme of ‘thanks’ having come back from summer holiday, where Sarah and I experienced the delights of the east coast of Yorkshire and a little of the moors. It was a first for us. Between Robin Hood’s bay, Whitby and many other places, we had a wonderful time. We also visited Rievaulx Abbey, which you can see in the picture. This is a truly special place to visit. Tucked in a tranquil valley of the North York Moors, you completely understand why the Cistercian monks built it there. The peace and tranquillity really lets you be who you are - to just ‘be’ in God’s presence. I also love these little cheeky chappies, who at one point would have adorned part of the building! We walk into September hopefully refreshed from the summer and with a great deal to be excited about and thankful for. On 9 September, we welcome Canon Richard Stainer as our new Rector for the Benefice. The service is at St Mary the Virgin Church, Stoke Bruerne at 7.30 p m. We would love to see as many of you as possible come to welcome Richard and his family and to give thanks for his ministry. Please pray for him as he prepares for that ministry. It is a full and rewarding ministry including leadership, teaching and pastoral care; of being a servant and shepherd amongst us all and in fostering the gifts of all God’s people. -

This Document Has Been Created by AHDS History and Is Based on Information Supplied by the Depositor

This document has been created by AHDS History and is based on information supplied by the depositor SN 3980 - Agricultural Census Parish Summaries, 1877 and 1931 This study contained a limited amount of documentation. The parish codes given below are to be used to interpret the data for the year of 1877. The parish codes for the 1931 data were not given in the initial deposit; consequently it is not possible to establish the parish of origin for the 1931 data. -

Housing Land Supply Mar 2009

Aylesbury Vale District Housing Land Supply Position as at end March 2009 – prepared May 2009 Introduction This document sets out the housing land supply position in Aylesbury Vale District as at the end of March 2009. Lists of sites included in the housing land supply are given in Appendices 1, 2 and 3. Two sets of calculations are provided: firstly for the five years April 2009 to March 2014, and secondly for the five years April 2010 to March 2015. Housing requirement The housing requirement for Aylesbury Vale is set out in the South East Plan (May 2009) (SEP). The figures are as follows: 2006-2011 2011-2016 Aylesbury 3,800 4,400 Rest of District 1,100 1,100 Total 4,900 (980 per annum) 5,500 (1,100 per annum) Note – Regional policy (South East Plan policies H1, MKAV 1, 2 and 3) sets an annual average figure for the above. The phasing shown in the above table is taken from the South East Plan Panel report (para 23.41 onwards and 23.127 onwards) and will be revisited in line with the Growth Investment and Infrastructure policy approach as outlined in Policy CS14 of the Core Strategy. Housing land supply for 1st April 2009 to 31st March 2014 SEP requirement 5,260 Pre-2009 deficit* 758 Total 5 year requirement 6,018 Projected supply from existing allocated sites (see Appendix 1) 3,223 Projected supply from other deliverable sites ≥ 5 dwellings (see Appendix 2) 1,034 Projected supply from sites less than 5 dwellings (see Appendix 3) 335 Total projected supply 4,592 Projected supply as percentage of requirement 76.3% (3.8 years) *In the period 2006 to 2009 the number of housing completions in Aylesbury Vale has not met the SEP requirement for that period, and therefore an additional 758 dwellings are needed to make up the deficit. -

![BUCKS.] FAR 546 [POST OFFIC£ Farmers-Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5079/bucks-far-546-post-offic%C2%A3-farmers-continued-1635079.webp)

BUCKS.] FAR 546 [POST OFFIC£ Farmers-Continued

[BUCKS.] FAR 546 [POST OFFIC£ FARMERs-continued. Cox E. W. Haddenham, Thame Dawkins W. Beaconsfield Clarke Elias, Lillingstone Dayrell, Cox G. Penn, Amersham Dawkins W. Coleshill, Amersbam Buckingham Cox J. Great Marlow Day J. & T. Mursley, Winslow ClarkeG.Lillingstone Dayrell,Buckingm Cox J. Denbam, Quainton, Winslow Day T. Caldecot, Bow brick hill, Bletch- Clarke G. Sympson, Bletcbley Station Cox J. Ibstone, Wallingford ley Station Clarke J. 8henley Brook end, Stony Cox W. Lane end, ·waddesdon, Aylesbry Dean J. Chartridge, Chesham Stratford Cox W. Haddenham, Thame Dean T. Huttons, Hambleden, Henley- Clarke J. Hogsbaw, Winslow Craft J. Hyde heath, Little Missenden, on-Thames Clarke J. B. Cbetwode, Buckingham Amersbam Dell J. Bledlow, Tring Clarke J. Low. Winchendon,Waddesdon Craft'I'.Brays green,Hundridge,Cheshm Dell J. Great 1.\'Iissenden, Amersham ClarkeJ .0.W aterStratford, Buckingham Cranwell J. Thornborough, Buckinghm Dell R. Prestwood common, Great Clarke R. King's hill, Little Missenden, Creswell G. St. Peter st. Great Marlow Missenden, Amersham Amersbam Creswell W. Wycombe rd. Gt. Marlow DellS. Ridge, Bledlow, Tring Clarke R. Three Households, Chalfont Crick C. Pin don end, Hanslope, Stony Denchfield J. Aston Abbotts, Aylesbury St. Giles, Slough Stratford Denchfield R.jun. Whitchurch,Aylesbury Clarke Mrs. S. Oving, Aylesbury Crick J. Hanslope, Stony Stratford Denchfield W. Akely, Buckingham Clarke S. Steeple Claydon, Winslow Cripps J. Dagnall, Eddlesborough, Deverell R. Stoke Mandeville, Aylesbury Clarke T. Lower Weald, Calverton, Dunstable Devrell J. Chemscott, Soulbury, Leigh- Stony Stratford Crook R. &. H. Oakley, Thame ton Buzzard Clarke T. C. Lit. Missenden, Amersham Crook E. Jxbill, Oakley, Thame Dickins E. Gran borough, Winslow Clarke W. -

CMK - Grange Park - Northampton X6 Effective From: 24/01/2021 Stagecoach Midlands

CMK - Grange Park - Northampton X6 Effective from: 24/01/2021 Stagecoach Midlands Monday to Friday Central Milton Keynes, Theatre District 0725 0855 0959 1059 1159 1259 1359 1501 1611 1743 1848 1943 Central Milton Keynes, Central Railway Station 0733 0904 1007 1107 1207 1307 1407 1512 1622 1755 1858 1953 Grafton Regis, White Hart PH 0753 0920 1021 1121 1221 1321 1421 1528 1645 1822 1915 2010 Roade, Churchcroft 0801 0928 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 1538 1653 1829 1921 2016 Grange Park, Lake 0812 0935 1037 1137 1237 1337 1437 1550 1705 1838 1927 2022 Delapre, Delapre Crescent 0827 0944 1046 1146 1246 1346 1446 1600 1719 1848 1937 2031 Northampton, Northampton Bus Interchange 0838 0954 1054 1154 1254 1354 1454 1609 1730 1856 1948 2039 Saturday Central Milton Keynes, Theatre District 0742 0828 0959 1059 1159 1259 1359 1511 1611 1741 1841 2013 Central Milton Keynes, Central Railway Station 0752 0836 1007 1107 1207 1307 1407 1519 1619 1749 1849 2021 Grafton Regis, White Hart PH 0809 0850 1021 1121 1221 1321 1421 1533 1633 1803 1903 2035 Roade, Churchcroft 0815 0856 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 1541 1641 1811 1911 2041 Grange Park, Lake 0821 0902 1037 1137 1237 1337 1437 1547 1647 1817 1917 2047 Delapre, Delapre Crescent 0830 0911 1046 1146 1246 1346 1446 1556 1656 1826 1926 2056 Northampton, Northampton Bus Interchange 0838 0921 1054 1154 1254 1354 1454 1604 1704 1834 1934 2104 Sunday Central Milton Keynes, Theatre District 0937 1032 1137 1232 1337 1432 1537 1632 1737 1832 1932 Central Milton Keynes, Central Railway Station 0945 1040 1145 1240 1345