Late Medieval Buckinghamshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advice from Buckinghamshire County Council to Aylesbury Vale District Council Concerning Changes to Housing Allocations

Advice from Buckinghamshire County Council to Aylesbury Vale District Council concerning changes to housing allocations Summary Following the VALP Examination in Public, AVDC and BCC commissioned additional transport modelling reports to further examine points raised during the EiP and in the Inspector’s Interim Conclusions which were: - BUC051 had been omitted from the Countywide modelling Phase 3 work - Concerns about the impact on Buckingham Town Centre of BUC051, and whether without mitigation BUC051 could be released on a phased basis - The need to identify additional housing sites This Advice Note sets out Buckinghamshire County Council’s view concerning the above issues taking into account the transport modelling work, previous planning applications and their transport assessments as well as our local knowledge of the transport network. Buckingham In relation to Buckingham, our view is that the detailed town centre modelling shows that BUC051 would have an unacceptable impact on the town centre, even if the development was phased. The only mitigation to congestion in the town centre that we have been able to identify is the Western Relief Road, as set out in the Buckingham Transport Strategy. However, it has been acknowledged that the scale of the proposed BUC051 allocation would be insufficient to provide funding for this mitigation measure. One option would be to increase the size of the allocation in order that the development was able to deliver the relief road. However, this would lead to a much larger allocation at Buckingham resulting in further modelling work being required to assess the potential impact on the A421. This suggestion does not take into account any site constraints such as flood risk. -

Careers in Buckinghamshire

Careers in Buckinghamshire LOCAL LABOUR MARKET INFORMATION FOR STUDENTS, SCHOOLS, PARENTS AND BUSINESSES CONTENTS The World of Work 2 The Local Picture in Buckinghamshire 3 Construction Sector 5 Health and Life Sciences Sector 6 High Performance Engineering Sector 7 INTRODUCTION Digital Technology Sector 8 Welcome to the Careers in Buckinghamshire Information Guide - full of local Labour Market Information to help with Space Sector 9 your future career. Here, you will find information on growing sectors in our Creative Sector 10 area, job roles that are in demand, skills you need to thrive in employment and a whole host of other useful information Manufacturing Sector 11 to ensure you are successful in your career. Buckinghamshire is home to many innovative, creative and Financial and Professional Services Sector 12 steadfast businesses as well as top - notch training providers. Wholesale and Retail Sector 13 The information provided in this booklet can be used by students, graduates, parents, schools and those seeking Education Sector 14 information on a career or sector as well as in conjunction with the new Bucks Skills Hub website, found at: Hospitality, Leisure and Tourism Sector 15 www.bucksskillshub.org Public Sector 16 Third and Voluntary Sectors 17 Buckinghamshire Enterprise Zones 18 Qualifications and Pathways 20 Skills for Employment 21 1 WHAT IS LMI ? LMI stands for 'Labour Market Information'. It can tell us the following: Industries and jobs which are growing Careers in or declining Certain jobs or skills that employers are looking for Salaries of different jobs Buckinghamshire The number of employees in different jobs Trends in employment jobs and industries. -

Statement of Consultation for the Wycombe District Local Plan

Wycombe District Council Statement of Consultation for the Wycombe District Local Plan DRAFT – September 2017 Wycombe District Local Plan – Statement of Consultation (draft - September 2017) This page is left intentionally blank 2 Wycombe District Local Plan – Statement of Consultation (draft - September 2017) Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5 Purpose of this report ..................................................................................................... 5 Scope of the Wycombe District Local Plan ..................................................................... 5 Timetable ...................................................................................................................... 6 Statement of Community Involvement ............................................................................ 7 Part 1. Who was consulted (Regulation 18)?...................................................................... 9 Part 2. How we consulted during the preparation of the Local Plan ................................... 10 Distribution of letters / emails ....................................................................................... 10 Information on Council website .................................................................................... 10 Documents available for inspection .............................................................................. 10 Weekly Planning Bulletin ............................................................................................. -

5350 the London Gazette, 12Th May 1970 Water

5350 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12TH MAY 1970 the Colchester and District Water Board (Water A copy of the application and of any map, plan Charges) Order, 1968. or other document submitted with it may be inspected The Board are authorised to supply water in the free of charge at the Board's Southern Area Office, areas or part of the areas of the following-named Mill End Road, High Wycombe, at all reasonable counties and districts: hours during the period beginning 8th May 1970. The administrative County of Cambridgeshire. and ending on 5th June 1970. The administrative County of Essex. This proposal is to enable the Bucks Water Board The administrative County of West Suffolk. to continue to abstract from existing boreholes and The Borough of Colchester. the proposed boreholes at their Mill End Road Pump- The Urban District of Braintree and Booking. ing Station a total daily quantity of 4,000,000 gallons. The Urban District of Halstead. Any person who wishes to make representations The Urban District of West Mersea. about the application should do so in writing to the The Urban District of Witham. Secretary, Thames Conservancy, Burdett House, 15 The Urban District of Wivenhoe. Buckingham Street, London W.C.2, before the end The Rural District of Braintree. of the said period. The Rural District of Chelmsford. R. S. Cox, Clerk and Treasurer of the Bucks The Rural District of Clare. Water Board. The Rural District of Dunmow. 1st May 1970. The Rural District of Halstead. The Rural District of Lexden and Winstree. The Rural District of Maldon. -

Buckinghamshire Green Belt Assessment Part 1A: Methodology

Buckinghamshire Green Belt Assessment Part 1A: Methodology 242368-4-05-02 Issue | 11 August 2015 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 242368-00 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd 13 Fitzroy Street London W1T 4BQ United Kingdom www.arup.com Document Verification Job title Buckinghamshire Green Belt Assessment Job number 242368-00 Document title Part 1A: Methodology File reference 242368-4-05-02 Document ref 242368 -4-05-02 Revision Date Filename Bucks GB Assessment Methodology Report DRAFT ISSUE 2015 03 18.docx Draft 1 18 Mar Description First draft for Steering Group review 2015 Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Max Laverack Andrew Barron Christopher Tunnell Signature Draft 2 26 Mar Bucks GB Assessment Methodology Report DRAFT ISSUE 2 - 2015 Filename 2015 03 26.docx Description Second draft for Stakeholder Workshop Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Max Laverack Andrew Barron Andrew Barron Signature Draft 3 27 Mar Bucks GB Assessment Methodology Report DRAFT ISSUE Filename 2015 STAKEHOLDERS - 2015 03 27.docx Description Draft Issue for Stakeholder Workshop Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Max Laverack Andrew Barron Andrew Barron Signature Draft 4 17 Apr Bucks GB Assessment Methodology - DRAFT 4 FINAL - 2015 04 Filename 2015 17.docx Description Draft Final Methodology, updated with Steering Group comments and comments received at Stakeholder -

1 Buckinghamshire; a Military History by Ian F. W. Beckett

Buckinghamshire; A Military History by Ian F. W. Beckett 1 Chapter One: Origins to 1603 Although it is generally accepted that a truly national system of defence originated in England with the first militia statutes of 1558, there are continuities with earlier defence arrangements. One Edwardian historian claimed that the origins of the militia lay in the forces gathered by Cassivelaunus to oppose Caesar’s second landing in Britain in 54 BC. 1 This stretches credulity but military obligations or, more correctly, common burdens imposed on able bodied freemen do date from the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the seventh and eight centuries. The supposedly resulting fyrd - simply the old English word for army - was not a genuine ‘nation in arms’ in the way suggested by Victorian historians but much more of a selective force of nobles and followers serving on a rotating basis. 2 The celebrated Burghal Hidage dating from the reign of Edward the Elder sometime after 914 AD but generally believed to reflect arrangements put in place by Alfred the Great does suggest significant ability to raise manpower at least among the West Saxons for the garrisoning of 30 fortified burghs on the basis of men levied from the acreage apportioned to each burgh. 3 In theory, it is possible that one in every four of all able-bodied men were liable for such garrison service. 4 Equally, while most surviving documentation dates only from 1 G. J. Hay, An Epitomised History of the Militia: The Military Lifebuoy, 54 BC to AD 1905 (London: United Services Gazette, 1905), 10. -

Land in Oxford and Great Marlow, Bucks., Bequeathed by John Browne (Master 1745–64), 1755-1971

1 UNIV ONLINE CATALOGUES UC:E23 - LAND IN OXFORD AND GREAT MARLOW, BUCKS., BEQUEATHED BY JOHN BROWNE (MASTER 1745–64), 1755-1971 John Browne, from Marton, Yorkshire, came up to University College in May 1704, and was elected a scholar in November 1705. He was then elected a Skirlaw Fellow on 23 August 1711. As a Fellow, Browne held many of the major offices of the College, in particular acting as Bursar during the 1720s. During the great Mastership dispute at the College of the 1720s, when two Fellows both claimed to be Master, Browne supported Thomas Cockman, the ultimate victor. In 1738 Brown was appointed Archdeacon of Northampton, and he resigned his Fellowship in February 1738/9. In 1745, however, he returned to University College on being elected Master. Brown remained Master, still retaining his archdeaconry, until his death on 7 August 1764. He had served as Vice-Chancellor from 1750–3. In addition to the preceding posts, Brown had also been vicar of Long Compton, Warks, for half a century, and in 1743 he was appointed a canon of Peterborough Cathedral. Browne had prospered in his ecclesiastical career, and he remained a bachelor. On his death in 1764, therefore, Browne proved a major benefactor to his old College. Not only did he bequeath his extensive library to the College for the use of successive Masters, but he also left a house at 88 High Street Oxford (now the site of Durham Buildings) and some property at Great Marlow, Buckinghamshire, to trustees, both to endow new undergraduate scholarships, but also to augment the stipends of existing scholarships whose value had declined with time. -

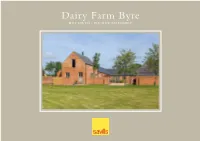

Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE View from the Front of the House

Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE View from the front of the house Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE Approximate distances: Buckingham 3 miles • M40 (J9) 9 miles • Bicester 9 miles Brackley 10 miles • Milton Keynes 14 miles • Oxford 18 miles. Recently renovated barn, providing flexible accommodation in an enviable rural location Entrance hall • cloakroom • kitchen/breakfast room Utility/boot room • drawing/dining room • study Master bedroom with dressing room and en suite bathroom Bedroom two and shower room • two further bedrooms • family bathroom Ample off road parking • garden • car port SAVILLS BANBURY 36 South Bar, Banbury, Oxfordshire, OX16 9AE 01295 228 000 [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text DESCRIPTION Entrance hall with double faced wood burning stove,(to kitchen and entrance hall) oak staircase to first floor, under stairs cupboard and limestone flooring with underfloor heating leads through to the large kitchen/breakfast room. Beautifully presented kitchen with bespoke units finished with Caesar stone work surfaces. There is a Britannia fan oven, 5 ring electric induction hob, built in fridge/freezer. Walk in cold pantry with built in shelves. East facing oak glass doors lead out onto the front patio capturing the morning sun creating a light bright entertaining space. Utility/boot room has easy access via a stable door, to the rear garden and bbq area, this also has limestone flooring. Space for washing machine and tumble dryer. Steps up to the drawing/dining room with oak flooring, vaulted ceiling and exposed wooden beam trusses. This room has glass oak framed doors leading to the front and rear west facing garden. -

Buckinghamshire. Wycombe

DIRECTORY.] BUCKINGHAMSHIRE. WYCOMBE. .:!19 Dist.rim Surveyor, .Arthur L. Grant, High st. Wycombe Oxfordshire Light Infantry (3rd Battalion) (Royal Bucb Samtary Inspectors, Arthur Stevens, Princes Risborough ~ilitia), Lieut.-Col. & Hon. Col. W. Terry, com .t Rowland H. Herring, Upper Marsh, High Wycombe manding; F. T. Higgins-Bernard & G. F. Paske, majors; .Major G. F. Paske, instructor of musketry ; PUBLIC ESTABLISHMENTS. Bt. Major C. H. Cobb, adjutant; Hon. Capt. W. Borough Police Station, Newland street; Oscar D. Spar Ross, quartermaster nt Bucks Rifle Volunteers (B & H Cos.), Capt. L. L. C. ling, head constable ; the force consists of I head con stable, 3 sergeants & 15 constables Reynolds (.B Co.) & Capt. Sydney R. Vernon (H Co.) ; head quarters, Wycombe Barracks Cemetery, Robert S. Wood, clerk to the joint com mittee; Thomas Laugh ton, registrar WYCXJM!BE UNION. High Wycombe & Earl of Beaconsfield Memorial Cottage Hospital, Lewis William Reynolds M.R.C.S.Eng. Wm. Board day, alternate mondays, Union ho.use, Saunderton, Bradshaw L.R.C.P.Edin. William Fleck M.D., M.Ch. at II a.m. Humphry John Wheeler M.D. & Geo. Douglas Banner The Union comprises the following place~: Bledlow. man M.R.C.S.Eng. medical officers; D. Clarke & Miss Bradenham, Ellesborough, Fingest, Hampden (Great & Anne Giles, hon. secs. ; Miss Mary Lea, matr<m Little), Hedsor, Horsendon, Hughenden, lbstone, County Court, Guild hall, held monthly ; His Honor Illmire, Kimble (Great. & Little), Marlow Urban, W. Howland Roberts, judge; John Clement Parker, Marlow (Great), Marlow (Little), Radnage, Monks registrar & acting high bailiff; Albert Coles, clerk. Rishorough, Princes Risboumgh, Saunderton, Stoken The following parishes & places comprise the dis church, Turville, Wendover, Wooburn, Wycombe trict :-.Applehouse Hill (Berks), .Askett, .Aylesbury End, (West), Chepping Wycombe Rural & Wycombe (High). -

14Th Regiment in NZ

14th REGIMENT OF FOOT (BUCKINGHAMSHIRE) 2nd BATTALION IN NEW ZEALAND 1860 - 1870 Private 1864 GERALD J. ELLOTT MNZM RDP FRPSL FRPSNZ AUGUST 2017 14th Regiment Buckinghamshire 2nd Battalion Sir Edward Hales formed the 14th Regiment in 1685, from a company of one hundred musketeers and pikemen recruited at Canterbury and in the neighbourhood. On the 1st January 1686, the establishment consisted of ten Companies, three Officers, two Sergeants, two corporals, one Drummer and 50 soldiers plus staff. In 1751 the Regiment officially became known as the 14th Foot instead of by the Colonel’s name. The Regiment was engaged in action both at home and abroad. In 1804 a second battalion was formed at Bedford, by Lieut-Colonel William Bligh, and was disbanded in 1817 after service in the Ionian Islands. In 1813 a third battalion was formed by Lieut-Colonel James Stewart from volunteers from the Militia, but this battalion was disbanded in 1816. The Regiment was sent to the Crimea in 1855, and Brevet Lieut-Colonel Sir James Alexander joined them after resigning his Staff appointment in Canada. In January 1858, the Regiment was reformed into two Battalions, and Lieut- Colonel Bell, VC., was appointed Lieut-Colonel of the Regiment. On 1 April 1858, the establishment of the 2nd Battalion was increased to 12 Companies, and the rank and file from 708 to 956. On the 23 April 1858, Lieut-Colonel Sir James Alexander assumed command of the 2nd. Battalion. Lieut-Colonel Bell returned to the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers. The 2nd. Battalion at this time numbered only 395 NCO’s and men, but by April 1859 it was up to full establishment, recruits being obtained mainly from the Liverpool district. -

Six Rides from Princes Risborough

Six cycle routes in to Aylesbury About the Rides Off road cycle routes Local Cycle Information The Phoenix Trail Monks A4010 9 miles and around PRINCES Risborough he rides will take you through the countryside and bridleways ocal cycle groups organise regular rides he Phoenix Trail is part A4129 to Thame around Princes Risborough within a radius of 5 in the Chiltern countryside. You are very of the National Cycle Whiteleaf ISBOROUGH miles (8km). Mountain bikes are recommended but o use off-road routes (mainly bridleways, which 8 miles R welcome to join these groups – contact i Network (Route 57). T can be uneven and slippery) you will need a some of the rides can be made on ordinary road bikes. L T using local roads, them for details of start points, times and distances. It runs for 7 miles on a disused Each ride has a distance, grading and time applied, but Tsuitable bike, such as a mountain bike. Mountain Princes these are only approximate. It is recommended that bike enthusiasts will find the trails around the Risborough railway track between Thame Risborough lanes and The Chiltern Society: cyclists carry the appropriate Ordnance Survey Explorer area quite challenging and the Phoenix Trail also offers all and Princes Risborough. www.chilternsociety.org.uk or 01949 771250. bridleways Maps. The conditions of the pathways and trails may vary types of bike riders the opportunity to cycle away from It is a flat route shared by cyclists, depending on the weather and time of year. traffic. If you ride off-road please leave gates as you find walkers and horse riders. -

Trades. Bre 263

BUCKUGHA:WS:SHlRE.] TRADES. BRE 263 J.awrence James k Son, Haddenham; Smith, Bartholomew George Edlcs- :BOOT & SHOE .REPAIRERS. Thame borough, Dul!stable Bailey Victor J. Crown la. Wycom~ Leslie Waiter, Chalfont St. Peter, .Smith }"rank, 3 William street,Slough Biggs S. 1 g Germain st. Chesham Gerrard's Cross S.O -lmith John, High street, Winslow Birch l''redk. Cnddington, .Aylesbury Litchfield Jn. Oxford st. Bletchley rd. ~m~th Joseph, 7 Oxford rd. Wycombel Gray C. Hambleden, Henley-on-Thm1 Fenny Stratford, Bletchley :Smith Wm. Park st. Bletchley road, Johnson Charles, Queen's rd. Marlow Loakes Frederick, Wing rd. Linslade, Fenny Stratford, Bletchley King James, Stratford rd.Buckingham Leighton Buzzard .Sonster James, New Bradwell, Wol- Lewis Thos. II Newland st. Wycombe Love Hy.H.New Bradwell,Wolvrtn.S.O verton S.O Newens Thomas, New road, Linslade, Lovell David, Tingewick, Buckingham Spicer John, Bierton, .Aylesbury Leighton Buzzard Lunnon & Ranee, West st. Marlow :Spring C. Brook st. Chalvey, Slough Roberts Bros.226 Desboro' rd.Wycmbe Lyman George, Stoke Goldington, 3tacey F. W. 5 Frogmoor gardens, Small Chas. Fdk. Haddenham,Thame Newport Pagnell Wycombe Mcllroy W. 7 & 13 Market sq . .Aylesbry ~tandage Geo. 1.1- Cre~don st. ~ycmbe :BRACE MANUFACTURERS Maguire & Son, 14 Brocas st. Eton, ::-.tone John, .As ton Clmton, Trmg _ . · Windsor Stroud William, London rd. Wycombe Duerdoth Frederick Wilham (& belt), Manton James, 17 Church street, Sutton John, Gerrard's Cross S.O 79 High street, Chesham Wolverton S.O Swift Robert, Padbnry, Buckingham Price & Almond, 105 & 107 Welling- Marchant C. R, Son & Garrard, Chal- Tapping Richard, Market pl.