Visual Saources in the History of Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2015

Worldwide Investigation and Prosecution of Nazi War Criminals (April 1, 2014 – March 31, 2015) An Annual Status Report Dr. Efraim Zuroff Simon Wiesenthal Center – Israel Office Snider Social Action Institute December 2015 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 5 Introduction 6 The Period Under Review: April 1, 2014 – March 31, 2015 8 Convictions of Nazi War Criminals Obtained During the Period Under Review 14 Convictions of Nazi War Criminals: Comparative Statistics 2001-2015 15 New Cases of Nazi War Criminals Filed During the Period Under Review 16 New Cases of Nazi War Criminals: Comparative Statistics 2001-2015 17 New Investigations of Nazi War Criminals Initiated During the Period Under Review 18 New Investigations of Nazi War Criminals: Comparative Statistics 2001-2015 19 Ongoing Investigations of Nazi War Criminals As of April 1, 2015 20 Ongoing Investigations of Nazi War Criminals: Comparative Statistics 2001-2015 21 Investigation and Prosecution Report Card 23 Investigation and Prosecution Report Card: Comparative Statistics 2001-2015 34 List of Nazi War Criminals Slated for Possible Prosecution in 2016 36 About the Simon Wiesenthal Center 37 Index of Countries 42 Index of Nazi War Criminals 44 3 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. During the period under review, the most significant progress in prosecuting Nazi war criminals has been made in Germany. This is clearly the result of the dramatic change instituted several years ago vis-à-vis suspected Holocaust perpetrators who served in death camps or Einsatzgruppen, who can now be successfully convicted of accessory to murder based on service alone. Previously, prosecutors had to be able to prove that a suspect had committed a specific crime against a specific victim and that the crime had been motivated by racial hatred to be able to bring a case to court. -

Visual Arts in the Urban Environment in the German Democratic Republic: Formal, Theoretical and Functional Change, 1949–1980

Visual arts in the urban environment in the German Democratic Republic: formal, theoretical and functional change, 1949–1980 Jessica Jenkins Submitted: January 2014 This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in partial fulfilment of its requirements) at the Royal College of Art Copyright Statement This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Art. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research for private study, on the understanding that it is copyright material, and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. Author’s Declaration 1. During the period of registered study in which this thesis was prepared the author has not been registered for any other academic award or qualification. 2. The material included in this thesis has not been submitted wholly or in part for any academic award or qualification other than that for which it is now submitted. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the very many people and institutions who have supported me in this research. Firstly, thanks are due to my supervisors, Professor David Crowley and Professor Jeremy Aynsley at the Royal College of Art, for their expert guidance, moral support, and inspiration as incredibly knowledgeable and imaginative design historians. Without a generous AHRC doctoral award and an RCA bursary I would not have been been able to contemplate a project of this scope. Similarly, awards from the German History Society, the Design History Society, the German Historical Institute in Washington and the German Academic Exchange Service in London, as well as additional small bursaries from the AHRC have enabled me to extend my research both in time and geography. -

Anti-Aircraft Fire Reports Circulate Ixermans;

TUESDAT, SEFTEMBER 24.1940 rWELVB Average Dally Circulation flattrbrsinr Eohtfna XmDk For Um Moath of Aagaot, 1B4B plla h «v « been discovered wbo The iRmbiem Ghib Will hold a Emergency Doctors 6331 Music Lessons otherwise might not have been. public bridge at t^ .E lk a home in Plaao Olaeees Board Studies Membor of Uw Audit - iU>out Town RMkville tomorrow a^moon at Physicians of the Manchester In connection with instrumental HALE'S SELF SERVE Buieaa of OIrenlatloaa 2:30. Mra J. R. Morin^Mr8. Al Medical Assoctatlon who will instruction, many pupila have in bert Heller, Mrs. Harry Dowdlng, -respond to emergency calls to Again Planned quired as to the possibility of AnnualReport The Orijdnfil In New England! Mmiehstfsp—A Ctfy of VtUago Chwrnt piliM Emma Lou Kehl«r, daugh- Mra. Anna Wllleke, Mrs. Jepnle morrow afternoon are Dm. having piano classes formed in the K Mr. and Mm. T. B. Kehler Burke, Mra. W. Burke are the George Lundberg and Alfred ■ sch(X>ls. If any local teacher is in MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, SEPTEBIBER 25,1940 ^ B o U d atreet h u returned to Rockville members on the commit'*^ Sundqulst. ____* Sixty-fiveTupHs Are En terested in teaching piano classes AudHor^s Suggestions AND HEALTH MARKET VOL. LIX., NO. 304 (ClaaoMod AdvorttMug oa Pago 14) kaca College for the second year tee, and Mrs. John Wilson, Man- In the acbpola, he may apply in her dramatic studies. During . Chester. rolled Already in the writing to Mr. Pearson, ataU ^ hla Are Presented; Other '^tba summer Miss Kehler has been Parents of cnlldrer attending the Sunday school of the Kmanuel Elementary Grades. -

East German Art Collection, 1946-1992

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft538nb0c2 No online items Guide to the East German art collection, 1946-1992 Processed by Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Steven Mandeville-Gamble. Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc © 2002 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the East German art M0772 1 collection, 1946-1992 Guide to the East German art collection, 1946-1992 Collection number: M0772 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Processed by: Special Collections staff Encoded by: Steven Mandeville-Gamble © 2002 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: East German art collection, Date (inclusive): 1946-1992 Collection number: M0772 Extent: 21 linear ft. (ca. 1300 items) Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Language: English. Access Restrictions None. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the repository. Literary rights reside with the creators of the documents or their heirs. To obtain permission to publish or reproduce, please contact the Public Services Librarian of the Dept. of Special Collections. Provenance Purchased, 1995. Preferred Citation: East German art collection. M0772. Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Historical note The collection was put together by Jurgen Holstein, a Berlin bookseller. -

Programme Forum for Academic Freedom by the Alliance of Science Organisations in Germany

SCHOLARS AT RISK NETWORK GERMANY SECTION Programme Forum for Academic Freedom by the Alliance of Science Organisations in Germany Supporting the Career Development of Researchers at Risk 18 – 19 March 2019, Berlin 2 | Table of Contents Welcome | 3 Table of Contents Welcome Welcome ............................................................................................................................... 3 Dear guests, Alliance of Science Organisations in Germany .......................................................................... 4 On behalf of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, it is my great pleasure to welcome you to the 2019 Forum for Academic Freedom. Convened in cooperation with the Alliance of Science Organisations in Germany and the Scholars at Risk Germany Section, the Forum Agenda & Supporters ............................................................................................................. 5 brings 250 participants from over 20 countries to Berlin to discuss the state of academic freedom in various regions of the world, foster exchange among and about scholar rescue programmes, and examine the imposing challenge of re-building sustainable perspectives for Conference Venue .................................................................................................................. 6 scholars who were forced from their laboratories, their desks, their homes. Programme ........................................................................................................................... 8 At the -

Games Industry a Guide 2018 to the German

2018 A GUIDE TO THE GERMAN GAMES INDUSTRY Cover_2018_v2.indd 223 23.02.2018 14:34:33 PREFACE BROCHURE ON GERMANY AS A IMPRINT & CONTACTS BUSINESS AND INVESTMENT LOCATION Dear Readers, Germany is one of the most important markets for computer and video games worldwide. No European country generates higher sales with games and the associated hardware. Germa- ny's benefits as a business location include its geographical position in the heart of Europe and its excellent infrastructure, as well as its Robinson: The Journey, the new VR game from membership in the EU and the uninhibited ex- change it therefore enjoys with over a half-bil- Crytek (creators of graphics engine CryENGINE), lion people on the continent. all major areas of the games industry. Germa- is a dream come true for fans of dinosaurs: a Germany is distinguished by a very lively ny also plays a special role in the e-sports games industry. A wide range of companies segment: some of the world’s largest tourna- whole world teeming with those beasts to explore. here are strong players on the world market. ments, the ESL One tournaments, take place Truly an adventure like no other. Some of these come from the browser and mo- here. And the ESL itself, one of the most im- bile games segment, including, for example, portant organisers of e-sports tournaments InnoGames, Travian Games and Wooga. In the and leagues in the world, is headquartered in area of PC and console games as well, German Germany. studios such as Deck 13 ('The Surge'), Mimi- Last but not least, Germany is the home mi Productions ('Shadow Tactics') and Yager of gamescom, which last year was opened by Entertainment ('Dreadnought') have recently Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel. -

Directories and Lists Jewish National Organizations in the United States

DIRECTORIES AND LISTS JEWISH NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS IN THE UNITED STATES *Indicates no reply was received Agudath Israel Youth Council of America Org. Sept., 1922. OFFICE: 616 Bedford Ave., Brooklyn, N. Y. Seventeenth Annual Convention, Oct. 21-22, 1939, New York City. Members, 1,500. PURPOSE: TO unite Jewish youth in the spirit of the Torah and in that spirit to solve the problems that confront Jewry in Palestine and in the Diaspora. OFFICERS: Hon. Pres., Isaac Strahl, 170 Broadway, N. Y. C; Pres., Michael G. Tress; Vice-Pres., Eli Basch; Leonard Willig; Treas., Charles Klein; Sec, Benjamin Hirsch. PUBLICATION: Agudah News. Aleph Zadik Aleph (Junior B'nai B'rith.) Org. May 3, 1924. OFFICE: 1003 K, N. W., Washington, D. C. Sixteenth Convention, June 21-28, 1939, Port Jervis, N. Y. Chapters, 310. Members, 8,500; 9,000 alumni. PURPOSE: Recreational and leisure-time program providing for the mental, moral and physical development of Jewish adolescents between the ages of 15 and 21. OFFICERS: Supreme Advisory Council: Pres., Sam Beber, Omaha, Neb.; Vice-Pres., Jacob J. Lieberman, Los Angeles, Cal.; Joseph Herbach, Philadelphia, Pa.; Treas., I. F. Goodman, San Antonio, Tex.; Exec. Sec, Julius Bisno, Washington, D. C; Asst. Exec. Sec, Ben Barkin, Washington, D. C.; Stanley Rabinowitz, Des Moines, la.; Lowell Adelson, Oakland, Cal.; Hyman Haves, New Haven, Conn.; Leo Bearman, Memphis, Tenn.; Alfred M. Cohen, Cincinnati, O.; Wilfred B. Feiga, Worcester, Mass.; Sidney Kusworm, Dayton, O.; Henry Monsky, Omaha, Neb.; Maurice Bisyger, Washington D. C.; Hyman M. Goldstein, Washington, D. C.; Nicholas M. Brazy, Ft. Wayne, Ind.; Walter Hadel, Los Angeles, Cal.; Jack Spitzer, Holly- wood, Cal. -

Trojan Trivia

TROJAN TRIVIA AFTER TIES — USC is 36-14-4 in games immediately following a tie. The director. Producers Hilton Green (a team manager) and Barney Rosenzweig (a Trojans have won the last 13 contests they have played after a tie, dating to Yell Leader) also were associated with the Trojan football program . 1968. HOMECOMING — USC has a 55-24-4 record in its Homecoming games, ARTIFICIAL TURF — USC is 22-11-1 in its last 34 games on artificial turf. dating back to the first such event in 1924. AUGUST RECORD — USC has a 5-2 (.714) all-time record while playing HOME JERSEYS — USC wore its home cardinal jerseys for the 2000 Kick- in the month of August. off Classic against Penn State (even though Troy was the visiting team) and for its BIG TEN COMPETITION — USC has won 27 of its last 35 games (and 34 1999 game at Hawaii (at the request of the Rainbows). Before that, the last time of its last 43) against Big Ten opponents. USC has twice played 3 consecutive USC wore cardinal in an opponent's stadium was against UCLA in the Rose Bowl games against Big Ten teams: Northwestern in the 1996 Rose Bowl, then Penn in 1982. By the way, the last time USC wore its road white jerseys at the Coli- State and Illinois in 1996, and Indiana in the 1968 Rose Bowl, then Minnesota seum was the 1960 Georgia game, because the Bulldogs only had red jerseys in and Northwestern in 1968. There have been 5 times (1962-68-72-76-89) when those days (USC also wore white jerseys at home on a regular basis during the USC has faced 3 Big Ten teams during a single season, but not consecutively. -

The Annual Updated Registry of the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery

Original Cardiovascular 505 German Heart Surgery Report 2016: The Annual Updated Registry of the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Andreas Beckmann1 Anne-Katrin Funkat2 Jana Lewandowski1 Michael Frie3 Markus Ernst4 Khosro Hekmat5 Wolfgang Schiller6 Jan F. Gummert7 Wolfgang Harringer8 1 German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Address for correspondence Andreas Beckmann, MD, Deutsche Langenbeck-Virchow-Haus, Berlin, Germany Gesellschaft fü r Thorax-, Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie [DGTHG], 2 Leipzig Heart Institute GmbH, Leipzig, Germany Langenbeck-Virchow-Haus, Luisenstr. 58-59, 10117 Berlin, Germany 3 FOM Hochschule für Oekonomie and Management, Essen, Germany (e-mail: [email protected]). 4 Clinic for Cardiac and Vascular Surgery, University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany 5 Department of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgery, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany 6 Clinic for Cardiac Surgery, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany 7 Clinic for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Heart and Diabetes Center NRW, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany 8 Clinic for Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Surgery, Klinikum Braunschweig gGmbH, Braunschweig, Germany Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;65:505–518. Abstract Based on a long-standing voluntary registry founded by the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (GSTCVS), well-defined data of all cardiac, thoracic, and vascular surgery procedures performed in 78 German heart surgery departments during the year 2016 are analyzed. In 2016, a total of 103,128 heart surgery procedures (implantable defibrillator, pacemaker, and extracardiac procedures excluded) were submitted to the registry. Approximately 15.7% of the patients were at least 80 years of age, resulting in an increase of 0.9% compared with the data of 2015. For 37,614 isolated coronary artery bypass grafting procedures (relationship on-/off- pump 4.4:1), an unadjusted in-hospital mortality of 2.9% was observed. -

Fanning the Flames of Hate: Social Media and Hate Crime∗

Fanning the Flames of Hate: Social Media and Hate Crime∗ Karsten M¨uller† and Carlo Schwarz‡ February 19, 2018 Abstract This paper investigates the link between social media and hate crime using hand- collected data from Facebook. We study the case of Germany, where the recently emerged right-wing party Alternative f¨urDeutschland (AfD) has developed a major social media presence. Using a Bartik-type empirical strategy, we show that right-wing anti-refugee sentiment on Facebook predicts violent crimes against refugees in otherwise similar municipalities with higher social media usage. To establish causality, we further exploit exogenous variation in major internet and Facebook outages, which fully undo the correlation between social media and hate crime. We further find that the effect decreases with distracting news events; increases with user network interactions; and does not hold for posts unrelated to refugees. Our results suggest that social media can act as a propagation mechanism between online hate speech and real-life incidents. JEL classification: D74, J15, Z10, D72, O35, N32, N34. Keywords: social media, hate crime, minorities, Germany, AfD ∗We are grateful to Sascha Becker, Leonardo Bursztyn, Mirko Draca, Evan Fradkin, Thiemo Fetzer, Fabian Waldinger, and seminar participants at the University of Chicago and the Leverhulme Causality Conference at the University of Warwick for their helpful suggestions. We would also like to thank the Amadeu Antonio Stiftung for sharing their data on refugee attacks with us. M¨ullerwas supported by a Doctoral Training Centre scholarship granted by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number 1500313]. Schwarz was supported by a Doctoral Scholarships from the Leverhulme Trust as part of the Bridges program. -

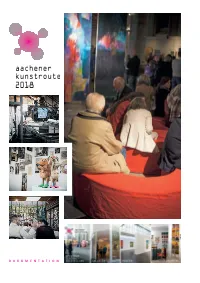

D O K U M E N T a T I

Doku Kunstroute 2018 (1.0).qxp_A4 Heft 25.10.18 13:00 Seite 1 DOKUMENTATION Doku Kunstroute 2018 (1.0).qxp_A4 Heft 25.10.18 13:00 Seite 2 Inhalt Seite 3 Fakten 4 Die 21. Aachener Kunstroute, Aachen am Kunstwochenende 6 Fotos der Ausstellungseröffnung SPEKTRUM 2018 8 Fotos der Aachener Kunstroute 2018 12 Teilnehmerliste 13 Stadtplan 14 Events 15 Gewinner des „Kunstwerks nach Wahl“ und der weiteren Preise 16 Website 18 52 Stationen der 21. Aachener Kunstroute 44 320 Künstler der 21. Aachener Kunstroute 48 Presseankündigungen 50 Presseberichte Aachener Kunstroute 51 Presseberichte Stationen 53 Terminanzeigen 54 Regionale Ankündigungen 57 Überregionale Ankündigungen 62 Die Aachener Kunstroute auf Instagram 2 Doku Kunstroute 2018 (1.0).qxp_A4 Heft 25.10.18 13:00 Seite 3 52 Stationen laden bei freiem Eintritt ein: Museen, Kunstvereine, Galerien und ausge- wiesene Künstlervereinigungen bieten Hochwertiges. Besuchen Sie Bewährtes und entdecken Sie neue Stationen wie das Büchelmuseum im Haus Rote Burg, das Galerie- atelier Karl von Monschau, Kunst Schoenen, Kunst- und Verlagshaus de Bernardi, die Produzentengalerie BB und weitere. In der »Aula Carolina« ist der Infopoint und die Ausstellung »SPEKTRUM*18« , die zentral einen ersten Einblick in die angebotene Kunst gibt. Meist fußläufig zu erreichen sind Vernissagen, Führungen, Lesungen und Musik. Über 300 ausstellende Künstlerinnen und Künstler, die meisten persönlich anwesend, zeigen Malerei, Zeichnung und Foto, sowie Objekt, Druckgrafik und Digital- druck, bis hin zu Performance, Installation -

PRESS KIT Behind the Mask: Artists in the GDR Press Conference On

PRESS KIT Behind the Mask: Artists in the GDR Press conference on October 26, 2017, at 11 am On the panel: Ortrud Westheider, Director, Museum Barberini Michael Philipp, curator, Museum Barberini Valerie Hortolani, guest curator, Museum Barberini Johanna Köhler, Head of Marketing and PR, Museum Barberini followed by a tour of the exhibition CONTENTS 1. Press release Behind the Mask: Artists in the GDR (pages 2) 2. Facts & figures on the exhibition Behind the Mask: Artists in the GDR (pages 4) 3. Facts & figures on the Museum Barberini collection (page 7) 4. Interview Johanna Pfund (Süddeutsche Zeitung) with Prof. Hasso Plattner on the Museum Barberini collection (pages 8) 5. Press release on the Palace Gallery (pages 10) 6. Publications (page 12) 7. Room notes Behind the Mask: Artists in the GDR (pages 13) 8. Summary of Palace Gallery documentation (pages 15) 9. Digital Visitors’ Book (page 18) 10. Press photos and credits for Behind the Mask: Artists in the GDR (pages 19) 11. Press photos and credits for Palace Gallery documentation (page 22) 12. Sources of loans to Behind the Mask: Artists in the GDR (pages 23) 13. What else is on at the Museum Barberini? (page 25) 14. Events (pages 26) 15. Advance notice: Max Beckmann: World Theater and other exhibitions in 2018 (pages 33) Addition: Complete list of works in Behind the Mask: Artists in the GDR Complete list of works in Palace Gallery documentation Wifi network: Presse; password: Presse285 Visuals available for download in optimized print quality via the link: www.museum-barberini.com/presse Johanna Köhler Museum Barberini gGmbH T +49 331 236014-305 Leiterin Marketing und PR/ Friedrich-Ebert-Str.