From Professionalisation to Global Ambitions: the History of History Writing at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

QU-Alumni-Review-2018-Issue-1.Pdf

Issue @, A?@F The magazine of Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario queensu.ca/alumnireview Queen’ALU MN IREVIsEW The waıstsueer Broaden your opportunities and take the rst step in your journey towards a Queen’s MBA Learn the fundamentals of business in just 4 months • Program runs May-August • Earn credits toward an MBA • Designed for recent graduates of any discipline • Broaden your career prospects For more inforo mation 855.933.3298 [email protected] ssb.ca/gdb contents Issue y, zxy, Volume z, Number y Serving the Queen’s community since yz queensu.ca/alumnireview p Queen’ALU MN IREVIsEW Editor’s notebook r From the principal: The water-conscious CAMPUS NEWS university on Clean s water Quid novi A critical mass for News from campus cutting-edge water research: learn about v the interdisciplinary Research news: approach of the Innovation in Beaty Water cancer research Research Centre. pv Research news: Road salt and the environment qn Keeping in touch notes ro ON Your global THE alumni network: COVER Branch events m o and news c Award-winning . t r conceptual illustrator a i 2 i Eric Chow adds a / rr w o tricolour splash to our Ex libris h c rainy day cover. c i New books from r illustration: E © © Eric chow, i2iart.com faculty and alumni l l a h . P l E a h c ou i m CAMPUS NEWS Working with water Swimmers and scientists, astronauts and artists: meet a few people who work with (or in) water. ed ito rs NO TEBOO’K On water, the arts, and football orking at this magazine is really special. -

Of Danes and Giants: Popular Beliefs About the Past in Early Modern England1 Among the Popular Beliefs That One Is Likely To

Daniel Woolf Of Danes and Giants: Popular Beliefs about the Past in Early Modern England1 Among the popular beliefs that one is likely to find in any society, whether it be a largely oral cu!ture of the sort studied in recent times by anthropologists, or a highly literate culture of the kind that predominates in the modem west, there is certain to be a large component which deals expressly with the past. A curiosity as to one's own origins, and the origins of one's material surroundings, is not the exclusive prerogative of literate societies, and still less of the educated elite in those societies; whether or not popular beliefs and traditions about the past actually reflect views held higher up the social ladder is thus in a certain sense-a non-question. It is more important to come to terms with what a given group, class or community believed about its own past, local or national, mythic, legendary or "historical," than it is to categorize these beliefs rigidly as either "popular" or "elite," though the cultural historian should properly remain aware at all times of their social context.2 The purpose of this essay is to offer a variety of examples illustrating several types of popular belief about the past, current in England between the end of the Middle Ages and the early eighteenth century. The word "popular" is here taken to mean "widely held" within a broad cross-section of society (even if only local society), a cross-section which generally included the middling and poorer elements of a community, but which might in some instances embrace members of an educated elite increasingly disposed to be crilical of "vulgar error. -

August 2010, Issue 3(Link Is External)

lorem ipsum issue #, date Issue 3, August 2010 NEWT NEWS Message from the Director Issue 3, August 2010 We’re delighted to update you with this issue of NewT News. I don't have to add anything to the details. They speak for themselves. The past In this Issue: year has been an extremely busy but also satisfying one as we have seen the fruits of our research collaboration mature and flourish. The Message from the Director workshops, the books, the completed dissertations, the academic 1 advancement and other markers all exude evidence of that. I The ‘Security Games’ Workshop congratulate the team for your achievements and for your ongoing Report work, new network configurations and your commitment to both high By Adam Molnar quality research and to well-placed research communication. 2 What strikes me particularly as I write is the timely nature of our work. Exhibiting Surveillance Every week, sometimes each day, newscasts include surveillance items By Jan Allen that demand our attention and indeed, are often accompanied by 3 comment from one team member or another. In the global north, the The Surveillance Studies Summer fall-out from 9/11 continues to bolster security states and thus drive the Seminar 2009 surveillance industry. In the global south, much commercial as well as By Jimena Valdés Figueroa global north pressure is placed on countries to adopt surveillance 4 techniques as part of their modernizing drives. Some surveillance serves Publications the cause of human rights and civil liberties but much, at the present 5 - 7 time, does not. Thus the ethical and political dimensions of our research Team News and Resources become ever more critical, as seen for example in the Vancouver Statement following the recent Surveillance Games workshop. -

Month Day Location Activity Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends Ontario Institute for Cancer Research

Principal Daniel Woolf: Schedule Highlights April 19 - October 3 , 2017 Month Day Location Activity Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends 19 Toronto Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) Board of Directors' Meeting Public Policy Forum 30th Annual Testimonial Dinner and Awards Meeting with the Prime Minister's Office 21 Ottawa Meeting with Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada Meeting with the Privy Council April 22 Kingston RSC Eastern Chapter Luncheon MNU Executive Board Teleconference 25 Montreal University Canada Meetings 26 University Canada Meetings 27 Venus Statue Reception and Dinner 28 Kingston COU's President David Lindsay Visit 1 Dinner with Faculty Member Meeting with MPP David Zimmer and MPP Sophie Kiwala - Truth and Reconcilliation 2 Meeting with Minister Deb Matthews Toronto Meeting with MPP Lisa Thompson - Truth and Reconcilliation 3 Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends 4 Celebration of Service COU Executive Teleconference 5 Ambassadors' Forum Kingston 6 Shirley Abramsky's Tribute Reception and Dinner Lunch with a Dean 8 Regular Meeting with AMS Executive Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends 10 Ottawa Meeting with the Prime Minister May U15 Meeting and Dinner 12/13 Kingston Board of Trustees Meetings Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends 19 Reception in Honour of Justice Kin Kee Pang Hong Kong 175th Anniversary Celebration - Reconvocation Ceremony and Reception 20 Reception and Gala Dinner 25 Toronto COU Executive Heads Roundtable Convocation Ceremony #3, #4 26 SNOLab Exhibit, New Eyes on the Universe , Opening -

European Regions and Boundaries European Conceptual History

European Regions and Boundaries European Conceptual History Editorial Board: Michael Freeden, University of Oxford Diana Mishkova, Center for Advanced Study Sofi a Javier Fernández Sebastián, Universidad del País Vasco, Bilbao Willibald Steinmetz, University of Bielefeld Henrik Stenius, University of Helsinki The transformation of social and political concepts is central to understand- ing the histories of societies. This series focuses on the notable values and terminology that have developed throughout European history, exploring key concepts such as parliamentarianism, democracy, civilization, and liberalism to illuminate a vocabulary that has helped to shape the modern world. Parliament and Parliamentarism: A Comparative History of a European Concept Edited by Pasi Ihalainen, Cornelia Ilie and Kari Palonen Conceptual History in the European Space Edited by Willibald Steinmetz, Michael Freeden, and Javier Fernández Sebastián European Regions and Boundaries: A Conceptual History Edited by Diana Mishkova and Balázs Trencsényi European Regions and Boundaries A Conceptual History ላሌ Edited by Diana Mishkova and Balázs Trencsényi berghahn N E W Y O R K • O X F O R D www.berghahnbooks.com Published in 2017 by Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com © 2017 Diana Mishkova and Balázs Trencsényi All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Mishkova, Diana, 1958– editor. | Trencsenyi, Balazs, 1973– editor. -

A Provincial Election Campaign Is Now in Full Swing, with Election Day Called for Thursday, June 12

PRINCIPAL AND VICE- CHANCELLOR Richardson Hall, Room 351 Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 3N6 Tel 613.533.2200 Fax 613.533.6838 Principal’s Written Report Queen’s University Senate May 2014 Government Update Provincial: • A provincial election campaign is now in full swing, with election day called for Thursday, June 12. The election was triggered when the NDP did not support the budget brought in by the minority Liberal government. • As a result of the campaign activity, the public service is now acting in a caretaker capacity, which means that no new policy or program initiatives can be introduced. It also restricts ongoing work, consultations, announcements and events. This situation will continue until the swearing-in of a new or returning government. • This arrangement does have some implications for Queen’s, namely: o That while our Strategic Mandate Agreement has now been signed by both parties, no further action will be taken at this time; o That meeting requests from universities to the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities have been turned down; do An that any provisions in the May 1 budget relevant to universities, such as the proposed pension framework, are now only considered as proposed, not approved. • I do make a point of offering to meet with candidates during a campaign to reinforce our priorities for the sector and for Queen’s. At this time, three of the four parties running in the riding of Kingston and the Islands have accepted my offer. Federal: • Together with several other U15 presidents and principals, I recently had an hour-long meeting with the Prime Minister. -

Historical Writing in Britain from the Late Middle Ages to the Eve of Enlightenment

Comp. by: pg2557 Stage : Revises1 ChapterID: 0001331932 Date:15/12/11 Time:04:58:00 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001331932.3D OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, 15/12/2011, SPi Chapter 23 Historical Writing in Britain from the Late Middle Ages to the Eve of Enlightenment Daniel Woolf Historical writing in Britain underwent extraordinary changes between 1400 and 1700.1 Before 1500, history was a minor genre written principally by clergy and circulated principally in manuscript form, within a society still largely dependent on oral communication. By the end of the period, 250 years of print and steadily rising literacy, together with immense social and demographic change, had made history the most widely read of literary forms and the chosen subject of hundreds of writers. Taking a longer view of these changes highlights continuities and discontinuities that are obscured in shorter-term studies. Some of the continu- ities are obvious: throughout the period the past was seen predominantly as a source of examples, though how those examples were to be construed would vary; and the entire period is devoid, with a few notable exceptions, of historical works written by women, though female readership of history was relatively common- place among the nobility and gentry, and many women showed an interest in informal types of historical enquiry, often focusing on familial issues.2 Leaving for others the ‘Enlightened’ historiography of the mid- to late eighteenth century, the era of Hume, Robertson, and Gibbon, which both built on and departed from the historical writing of the previous generations, this chapter suggests three phases for the principal developments of the period from 1400 to 1 I am grateful to Juan Maiguashca, David Allan, and Stuart Macintyre for their comments on earlier drafts of this essay, which I dedicate to the memory of Joseph M. -

Members of Council, 2015-2016

Members of Council, 2015-2016 EXECUTIVE HEADS Algoma University Brock University Carleton University University of Guelph Lakehead University Laurentian University McMaster University Nipissing University OCAD University University of Ontario University of Ottawa Dr. Craig Chamberlin Dr. Jack Lightstone Dr. Roseann O’Reilly Runte Dr. Franco Vaccarino Dr. Brian Stevenson Mr. Dominic Giroux Dr. Patrick Deane Dr. Mike DeGagné Dr. Sara Diamond Institute of Technology Mr. Allan Rock President and President and President and President and President and President and President and President and President and Dr. Tim McTiernan President and Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor President and Vice-Chancellor Chair of Council Vice-Chancellor Queen’s University Ryerson University University of Toronto Trent University University of Waterloo Western University Wilfrid Laurier University University of Windsor York University Associate Member: Council of Council of Dr. Daniel Woolf Dr. Mohamed Lachemi Dr. Meric Gertler Dr. Leo Groarke Dr. Feridun Hamdullahpur Dr. Amit Chakma Dr. Max Blouw Dr. Alan Wildeman Dr. Mamdouh Shoukri Royal Military College Ontario Universities Ontario Universities Principal and Interim President and President President and President and President and President and President and President and of Canada Prof. Bonnie M. Patterson Mr. David Lindsay Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor Dr. Harry Kowal President and CEO President and CEO Vice-Chair of Council Principal (to December 31, 2015) (as of January 1, 2016) ACADEMIC COLLEAGUES Algoma University Brock University Carleton University University of Guelph Lakehead University Laurentian University McMaster University Nipissing University OCAD University University of Ontario University of Ottawa Dr. -

'Free to Do Whatever They Want': Why Universities Can Punish Students for Off-Campus Behaviour

'Free to do whatever they want': Why universities can punish students for off-campus behaviour cbc.ca/news/canada/queens-university-costume-party-racist-code-conduct-1.3864531 Queen's University students who attended a controversial costume party last weekend could be punished for violating the school's code of conduct — a set of rules implemented by many universities that includes off-campus, non-academic behaviour. But Timothy Boyle, a Calgary-based lawyer who has represented students involved in university disciplinary cases, said many schools may be extending their authority too far. "Fair enough they have certain standards to expect of you as a student while you're on campus," he said. "But now ... they want to extend themselves past their university boundaries and start regulating [students'] affairs while they are off campus. That has to be a great concern." Daniel Woolf, principal and vice chancellor of Queen's University, has said the university is investigating the off- campus party, an event that sparked accusations of racism. The party included students dressed up as Middle Eastern sheiks, Buddhist monks, Viet Cong fighters in rice hats and Mexican prisoners. Some of the students dressed up as Viet Cong fighters wearing rice hats. (Twitter) "We do have a student code of conduct which was revised last year," Woolf said. "Once we've concluded our investigation, if appropriate, there are actions that can be taken under the code." Queen's code of conduct says students are "expected to adhere to and promote the university's core values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect and personal responsibility in all aspects of university life, academic and non- academic." Racists, dummies and bad costumes: Robyn Urback Queen's investigates 'shockingly racist' costume party The code can apply to non-academic misconduct that occurs on or off university property. -

Andrew Whiteleather F Am.Ily Geneology

Andrew Whiteleather F am.ily Geneology Compiled by Martha Whiteleather Monnette With the Assistance of Many Others 1966 The sources of information contained in the succeeding pages are as follows: The Whiteleather Family Tree drawn by Charles Mead oi North Georgetown, Ohi(\, ,Whiteleather Reunion correspondence undertaken by Rena Whiteleather of North Georgetown and George R. Floyd of Al liance, who were for many years Secretary and President respec tively of the Reunion, and Data contributed by mail and telephone in response t0 solicitations made over an eight year p~riod. Despite much work there are bound to be inaccuracies because of conflicting information from different sources and faulty mem ories of some· who supplied information. Serious attempts have been made to verify doubtful information. Please correct names and dates that are wrong so that you can pass the book on to your descendants in an accurate version. The numbers in parentheses immediately following name:.; of members of the family indicate the generation after Andrev, Whiteleather. Compilations of the history of the Whiteleather Family have been taken from records made by Rena Whiteleather of North Georgetown, for many years the secretary of the Whiteleather Reun ions of Ohio, and by Melvin K. Whiteleather, world-traveled news paper correspondent, radio commentator and lecturer. These two stories differ in a few respects, but both are extremely interesting, and, since they complement each other, both are given CONTENTS History by Rena Whiteleather . ................... 3 History by Melvin K. Whiteleather .......................... 5 Andrew Whiteleather -- the immigrant . ......... 7 Elizabeth Whiteleather Zimmerman Branch . 8-9 Mary Whiteleather Woolf Branch ............. -

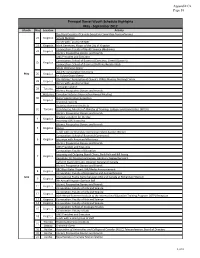

Principal Daniel Woolf: Schedule Highlights

Appendix Ca Page 18 Principal Daniel Woolf: Schedule Highlights May - September 2012 Month Day Location Activity The Royal Society of Canada Executive Committee Teleconference 22 Kingston Senate Meeting Dinner with Faculty member 23 Kingston Mark Gerretsen, Mayor of the City of Kingston Convocation: Faculty of Health Science (Medicine) 24 Kingston Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends AMS President and Executive Convocation: School of Business (Executive; Cornell/Queen's) 25 Kingston Convocation: School of Business (Fulltime/Accelerated) MiniU Welcome Dinner 2012 Re-convocation ceremony May 26 Kingston Tri-Colour Guard Dinner The Retirees' Association of Queen's (RAQ) Monday Morning Forum 28 Kingston Dinner with Faculty member Campaign Cabinet 29 Toronto Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends Waterloo Canadian Historical Association Annual Meeting 30 Donor Appreciation Reception Kingston Grant Hall Society Historica-Dominion Institute 31 Toronto Glen Murray, Minister of Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities (MTCU) Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends Shadow a student for the day 4 Kingston Incoming SGPS Executive Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends 5 Kingston Rector Lunch with the Chocolate Connection Silent Auction Winner Convocation: School of Business (Commerce) 6 Kingston Interview with American Milestones Alumni, Prospective Donors and Friends AMS President and Executive Convocation: Faculty of Education Incoming and Outgoing Board Chairs, Barb Palk and Bill Young 7 Kingston Reception for Douglas Hargreaves, Honorary