179 Local Museums in the Epistemic Context of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arachnida: Araneae) from Dobruja (Romania and Bulgaria) Liviu Aurel Moscaliuc

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © 31 août «Grigore Antipa» Vol. LV (1) pp. 9–15 2012 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-012-0001-2 NEW FAUNISTIC RECORDS OF SPIDERS (ARACHNIDA: ARANEAE) FROM DOBRUJA (ROMANIA AND BULGARIA) LIVIU AUREL MOSCALIUC Abstract. A number of spider species were collected in 2011 and 2012 in various microhabitats in and around the village Letea (the Danube Delta, Romania) and on the Bulgarian Dobruja Black Sea coast. The results are the start of a proposed longer survey of the spider fauna in the area. The genus Spermophora Hentz, 1841 (with the species senoculata), Xysticus laetus Thorell, 1875 and Trochosa hispanica Simon, 1870 are mentioned in the Romanian fauna for the first time. Floronia bucculenta (Clerck, 1757) is at the first record for the Bulgarian fauna. Diagnostic drawings and photographs are presented. Résumé. En 2011 et 2012, on recueille des espèces d’araignées dans des microhabitats différents autour du village de Letea (le delta du Danube) et le long de la côte de la Mer Noire dans la Dobroudja bulgare. Les résultats sont le début d’une enquête proposée de la faune d’araignée dans la région. Le genre Spermophora Hentz, 1841 (avec l’espèce senoculata), Xysticus laetus Thorell, 1875 et Trochosa hispanica Simon, 1870 sont mentionnés pour la première fois dans la faune de Roumanie. Floronia bucculenta (Clerck, 1757) est au premier enregistrement pour la faune bulgare. Aussi on présente les dessins de diagnose et des photographies. Key words: Spermophora senoculata, Xysticus laetus, Trochosa hispanica, Floronia bucculenta, first record, spiders, fauna, Romania, Bulgaria. INTRODUCTION The results of this paper come from the author’s regular field work. -

The Zooplankton of the Danube-Black Sea Canal in the First Two Decades of the Ecosystem Existence Victor Zinevici, Laura Parpală, Larisa Florescu, Mirela Moldoveanu

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © 30 décembre «Grigore Antipa» Vol. LVI (2) pp. 227–251 2013 DOI: 10.2478/travmu-2013-0017 THE ZOOPLANKTON OF THE DANUBE-BLACK SEA CANAL IN THE FIRST TWO DECADES OF THE ECOSYSTEM EXISTENCE VICTOR ZINEVICI, LAURA PARPALĂ, LARISA FLORESCU, MIRELA MOLDOVEANU Abstract. This paper reports the invasive subspecies Podonevadne trigona ovum (Zernov, 1901), as dominant in the Danube-Black Sea Canal. In the first two years of the existence of the anthropogenic ecosystem (1985-1986) the zooplankton summarizes only 72 species. Over two decades it recorded the presence of 127 species. As a result of nutrient accumulation, in 2005, the zooplankton abundance has significantly increased, reaching 330 ind L-1, followed by an evident growth of biomass (2285 μg wet weight L-1). In 2005, the productivity registered 731.8 μg wet weight L-1/24h. Résumé. Le présent papier rapport l’existence de la sous-espèce envahissante Podonevadne trigona ovum (Zernov, 1901), dominante dans le canal Danube – Mer Noire. La sous-espèce appartient à l’ordre Onychopoda, et elle a une origine Caspienne. Dans les premières deux années qui suit l’apparition de cet écosystème anthropogénique (1985-1986), le zooplancton a été reprèsenté par 72 espèces; après deux décennies, le nombre d’espèces a augmenté à 127. A la suite d’accumulation de nutriments, en 2005 l’abondance du zooplancton a augmentée de manière significative, atteignant 330 ind L-1, suivie d’une augmentation marquée de la biomasse (2285 mg s.um. L-1). En 2005, la productivité du zooplancton a enregistré 731,8 mg mat.hum. -

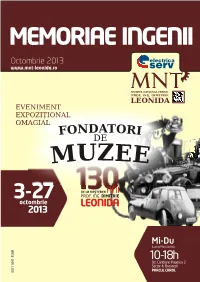

MEMORIAE INGENII Octombrie 2013

MEMORIAE INGENII Octombrie 2013 www.mnt-leonida.ro EVENIMENT EXPOZIȚIONAL OMAGIAL FONDATORI DE MUZEE 3-27 130ANI octombrie 2013 Mi-Du (Luni si Marti inchis) 10-18h Str. Candiano Popescu 2 Sector 4, Bucuresti PARCUL CAROL ISSN 1841-1568 MEMORIAE INGENII ISSN 1841-1568 www.mnt-leonida.ro Octombrie 2013 SUMAR Exerciţiu de memorie / Cristina UNTEA 1 Muzee şi fondatori / Laura Maria ALBANI, Director Muzeul Național Tehnic 2 “Prof. Ing. Dimitrie Leonida” Viaţa şi opera baronului Samuel von Brukenthal / Prof. univ. dr. Sabin Adrian LUCA, 5 Director General Muzeul Național Brukenthal - Sibiu Grigore Antipa - Fondatorul instituţiei care îi poartă numele şi inventatorul expoziţiilor 13 muzeale, dioramatice / Dumitru MURARIU, Director General al Muzeului Național de Istorie Naturală “Grigore Antipa“ Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaş: un părinte fondator / Dr. Virgil Ștefan NIȚULESCU, 18 Director General Muzeul Național al Țăranului Român Dimitrie Gusti (1880-1955) / Conf. Univ. dr. Paula POPOIU, Director General 20 Muzeul Național al Satului “Dimitrie Gusti” Momente şi personalităţi ce au marcat înfiinţarea şi evoluţia Muzeului Ştiinţei şi Tehnicii 24 „Ştefan Procopiu” din Iaşi / Ing. Teodora-Camelia CRISTOFOR, muzeograf Muzeul Științei și Tehnicii „ŞTEFAN PROCOPIU” din IAŞI George Enescu – date biografice / dr. Adina SIBIANU, muzeograf 36 Muzeul Național “George Enescu” Observatorul Astronomic „Amiral Vasile Urseanu” și ctitorul său / Ref. Mihai Dascălu, 41 Muz. Șonka Adrian Muzeul Municipal Râmnicu Sărat – consideraţii asupra istoricului constituirii colecţiilor / 43 Marius NECULAE, Roxana VIŞAN Dimitrie Leonida - promotor al construirii unei reţele de canale navigabile interioare în 48 România / Aurel TUDORACHE, muzeograf Muzeul Național Tehnic “Prof. Ing. Dimitrie Leonida” Dimitrie Leonida – una din luminile Fălticenilor / Ovidiu MUSTAȚĂ 52 Povestea fotografiei (scurtă cronologie a tehnicii fotografice) / Ing. -

Taxons Dedicated to Grigore Antipa

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle “Grigore Antipa” 62 (1): 137–159 (2019) doi: 10.3897/travaux.62.e38595 RESEARCH ARTICLE Taxons dedicated to Grigore Antipa Ana-Maria Petrescu1, Melania Stan1, Iorgu Petrescu1 1 “Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History, 1 Şos. Kiseleff, 011341 Bucharest 1, Romania Corresponding author: Ana-Maria Petrescu ([email protected]) Received 18 December 2018 | Accepted 4 March 2019 | Published 31 July 2019 Citation: Petrescu A-M, Stan M, Petrescu I (2019) Taxons dedicated to Grigore Antipa. Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle “Grigore Antipa” 62(1): 137–159. https://doi.org/10.3897/travaux.62.e38595 Abstract A comprehensive list of the taxons dedicated to Grigore Antipa by collaborators, science personalities who appreciated his work was constituted from surveying the natural history or science museums or university collections from several countries (Romania, Germany, Australia, Israel and United States). The list consists of 33 taxons, with current nomenclature and position in a collection. Historical as- pects have been discussed, in order to provide a depth to the process of collection dissapearance dur- ing more than one century of Romanian zoological research. Natural calamities, wars and the evictions of the museum’s buildings that followed, and sometimes the neglection of the collections following the decease of their founder, are the major problems that contributed gradually to the transformation of the taxon/specimen into a historical landmark and not as an accessible object of further taxonomical inquiry. Keywords Grigore Antipa, museum, type collection, type specimens, new taxa, natural history, zoological col- lections. Introduction This paper is dedicated to 150 year anniversary of Grigore Antipa’s birth, the great Romanian scientist and the founding father of the modern Romanian zoology. -

Seismic Response of Tropaeum Traiani Monument, Romania, Between History and Earthquake Engineering Assessments

SEISMIC RESPONSE OF TROPAEUM TRAIANI MONUMENT, ROMANIA, BETWEEN HISTORY AND EARTHQUAKE ENGINEERING ASSESSMENTS Emil-Sever GEORGESCU 1 The stone structure of triumphal monument Tropaeum Traiani was completed by Romans in 109 A.D in the North-Eastern part of Moesia Inferior, the present land of Romanian Province Dobrudja, between Danube and the Black Sea. It consisted of a stepped base, a large cylindrical drum covered with metopes – sculptured scenes of battle, with a truncated conical part over it, continued with a central hexagonal tower having a platform to support the inscriptions, statues of local prisoners and a tall military trophy, the main symbol of victory of Romans over warriors of Dacia and their allies. The diameter of the drum was some 40…43 m and the total height of monument reached some 37…40 m. It is likely to have been based on a design of Apollodor of Damascus, as it was the symbolic pair of Traian’s Column in Rome, with 29.78 m height, erected in 115 AD. The site included a funerary military altar for the Roman soldiers fallen in the battles and a tumulus tomb. A fortified Roman City named also Tropaeum Traiani was settled nearby. (Tocilescu et al, 1895; Florescu, F.B., 1965; Barnea et al, 1979; Sampetru, 1984) Almost all authors agreed that the upper part of the monument could have been destroyed by an earthquake, within some centuries after erection, while the sculpted metopes were dismantled, most probably by people, in a later age (Tocilescu et al, 1895; Sampetru, 1984); a hypothesis of a reconstruction in the III-rd century was suggested (Dorutiu-Boila, 1987). -

Migration Strategies of Common Buzzard (Buteo Buteo Linnaeus

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle «Grigore Antipa» Vol. 60 (2) pp. 537–545 DOI: 10.1515/travmu-2017-0008 Research Paper Migration Strategies of Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo Linnaeus, 1758) in Dobruja Cătălin-Răzvan STANCIU1, Răzvan ZAHARIA2, Gabriel-Bogdan CHIȘAMERA4, Ioana COBZARU3, *, Viorel-Dumitru GAVRIL3, 1, Dumitru MURARIU3 1Faculty of Biology, University of Bucharest, 91–95 Splaiul Independenței, 5050095 Bucharest, Romania 2Oceanographic Research and Marine Environment Protection Society Oceanic-Club, Constanța, Romania 3Institute of Biology Bucharest of Romanian Academy, 296 Splaiul Independenței, 060031 Bucharest, Romania 4“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History, 1 Kiseleff Blvd., 011341, Bucharest, Romania *corresponding author, email: [email protected] Received: August 2, 2017; Accepted: August 31, 2017; Available online: August 31, 2017; Printed: December 31, 2017 Abstract. We studied various aspects regarding migration behavior of the Common Buzzard for two subspecies (B. b. buteo and B. b. vulpinus) transiting the region which overlaps with the Western Black Sea Corridor. Using vantage points set across Dobruja we managed to count 2,662 individuals. We highlighted the seasonal and diurnal peak passage, flight directions and height of flight for each season. Our results suggest that 57% of the counted individuals belongs to long-distance migrant Steppe Buzzard - B. b. vulpinus. The peek passage period in autumn migration was reached between the 26th of September to the 6th of October, while for the spring migration peek passage remained uncertain. The main autumn passage direction was from N to S, and NNW to SSE but also from NE to SW. For spring passage the main direction was from S to N but also from ESE to WNW. -

Terrestrial Vertebrates of Dobrogea – Romania and Bulgaria

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © Décembre Vol. LIII pp. 357–375 «Grigore Antipa» 2010 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-010-0027-2 TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATES OF DOBROGEA – ROMANIA AND BULGARIA DUMITRU MURARIU, GABRIEL CHIªAMERA, ANGELA PETRESCU, IVANKA ATANASOVA, IVAYLO RAYKOV Abstract. The authors report the state of the terrestrial vertebrates of Romanian and Bulgarian Dobrogea. Five amphibian species, eight of reptiles, 159 of birds and 39 mammals species were inventoried. Some of them are characteristic to the steppe areas, in which Dobrogea is included, and others (as amphibians) have a limited distribution, around water flows, pools and lakes. Some of the observed or collected species have populations which can be compared in the two parts of Dobrogea, while the others (e.g. Crocidura suaveolens, Mesocricetus newtoni, Microtus arvalis) have populations more numerous in the Bulgarian Dobrogea, this thing indicating that there are several undamaged habitats and a low anthropic pressure than in the Romanian one. Résumé. Dans le cadre du contrat de collaboration roumaino-bulgare des années 2008-2009, soutenu par les Ministères de la Recherche Scientifique des deux pays, on a étudié les vertébrés terrestres de la Dobrogea roumaine (départements de Tulcea et Constanþa) et de la Dobrogea bulgare (départements de Silistra et Dobrich). Au cours des deux années on y a observé, prélevé ou inventorié (sur la base des informations de terrain) un nombre de 211 vertébrés terrestres: 5 espèces d’amphibiens, 8 de reptiles, 159 d’oiseaux et 39 de mammifères. Les amphibiens y sont les vertébrés avec la plus réduite biodiversité, le plus grand nombre d’espèces appartenant à la classe des oiseaux. -

Scientific Heritage of Alexandru Roşca: Publications, Spider Collection, Described Species

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Arachnologische Mitteilungen Jahr/Year: 2016 Band/Volume: 51 Autor(en)/Author(s): Fedoriak Mariia, Voloshyn Volodymyr, Moscaliuc Liviu Aurel Artikel/Article: Scientific heritage of Alexandru RoÅŸca: publications, spider collection, described species 85-91 © Arachnologische Gesellschaft e.V. Frankfurt/Main; http://arages.de/ Arachnologische Mitteilungen / Arachnology Letters 51: 85-91 Karlsruhe, April 2016 Scientific heritage of Alexandru Roşca: publications, spider collection, described species Mariia Fedoriak, Volodymyr Voloshyn & Liviu Aurel Moscaliuc doi: 10.5431/aramit5113 Abstract: The scientific heritage of the Romanian arachnologist Alexandru Roşca (publications, spider collection, and described species) was surveyed. For almost 40 years Alexandru Roşca studied the spiders from territories that are now parts of Romania, Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Moldova. Despite political repression, Roşca made a significant contribution to the study of the spiders of Romania and bordering countries, reflected in his 19 papers including the Ph.D. thesis. A complete list of Roşca’s papers is presented. The ‘Alexandru Roşca’ spider collection is deposited in the Grigore Antipa National Museum of Natural History (Bucharest, Romania). According to the register it in- cludes 596 species (1526 specimens) of spiders. Part of the collection was revised by different scientists and later by the present authors. During the period 1931–1939, Roşca described 13 spider species. To date, five species names have been synonymised. We propose that six species should be treated as nomina dubia because of their poor descriptions and lack of availability of types and/or other speci- mens. For two of Roşca’s species, Pardosa roscai (Roewer, 1951) and Tetragnatha reimoseri (Roşca, 1939), data and figures are presented and information on them is updated. -

REPORT 2.6 Report on Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA)

Project co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund through Operational Program for Technical Assistance 2007-2013 REPORT 2.6 Report on Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) c October 2015 This report relates to the deliverable “Output 2.6 – Report on Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA)” under the Agreement for Technical Assistance with regard to the Danube Delta Integrated Sustainable Development Strategy between the Ministry of Regional Development and Public Administration of Romania (MRDPA) and the World Bank for Reconstruction and Development, concluded on 4 September 2013. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................... 14 2 INFORMATION REGARDING THE DDISDS SUBJECT OF APPROVAL .................................................... 16 2.1 GENERAL INFORMATION REGARDING THE DDISDS ................................................................................... 16 2.2 GEOGRAPHIC AND ADMINISTRATIVE LOCATION ........................................................................................ 21 2.3 PHYSICAL MODIFICATIONS RESULTED FROM THE DDISDS IMPLEMENTATION ................................................. 26 2.4 NATURAL RESOURCES NECESSARY FOR THE DDISDS IMPLEMENTATION ........................................................ 27 2.5 NATURAL RESOURCES WHICH WILL BE EXPLOITED FROM THE NATURAL PROTECTED AREAS OF COMMUNITY IMPORTANCE IN ORDER TO BE USED FOR THE DDISDS IMPLEMENTATION ............................................................. -

First Meeting of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Black Sea Constanta, Romania, 16-18 January 2012

GFCM:SAC14/2012/Inf.17 GENERAL FISHERIES COMMISSION FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN COMMISSION GÉNÉRALE DES PÊCHES POUR LA MÉDITERRANÉE SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE (SAC) Fourteenth Session Sofia, Bulgaria, 20-24 February 2012 Report of the First meeting of the ad hoc Working Group on the Black Sea Constanta, Romania, 16-18 January 2012 OPENING, ARRANGEMENT OF THE MEETING AND ADOPTION OF AGENDA 1. The “First meeting of the ad hoc Working Group on the Black Sea” was held at the National Institute for Marine Research and Development Grigore Antipa in Constanta, Romania, from 16 th to 18 th January 2012. The meeting was attended by 48 experts from the Black Sea riparian countries (Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, the Russian Federation, Turkey and Ukraine), as well as by representatives of the European Union (EU), the Black Sea Commission (BSC), the Community Control Fishery Agency (CFCA), the European Inland Fisheries and Aquaculture Advisory Commission (EIFAAC), EUROFISH, FAO and the GFCM Secretariat. The list of Participants is provided in Appendix B of this report. 2. Mr Simion Nicolaev, Director of the National Institute for Marine Research and Development Grigore Antipa , welcomed the participants stating it was an honor to organize the First meeting of this Working Group in Constanta, given the importance of the meeting not only for Romania but also for the whole Black Sea area. He underlined the need to start a real cooperation in the region under this GFCM initiative, which is a great opportunity to further develop the GFCM experience into the Black Sea area and a challenge because of the lack of comprehensive and operative management tools to enforce cooperation mechanisms. -

Arhive Personale Şi Familiale

Arhive personale şi familiale Vol. II Repertoriu arhivistic Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ISBN 973-8308-08-9 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ARHIVELE NAŢIONALE ALE ROMÂNIEI Arhive personale şi familiale Vol. II Repertoriu arhivistic Autor: Filofteia Rînziş Bucureşti 2002 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ● Redactor: Alexandra Ioana Negreanu ● Indici de arhive, antroponimic, toponimic: Florica Bucur ● Culegere computerizată: Filofteia Rînziş ● Tehnoredactare şi corectură: Nicoleta Borcea ● Coperta: Filofteia Rînziş, Steliana Dănăilescu ● Coperta 1: Scrisori: Nicolae Labiş către Sterescu, 3 sept.1953; André Malraux către Jean Ajalbert, <1923>; Augustin Bunea, 1 iulie 1909; Alexandre Dumas, fiul, către un prieten. ● Coperta 4: Elena Văcărescu, Titu Maiorescu şi actriţa clujeană Maria Cupcea Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei CUPRINS Introducere ...................................................................... 7 Lista abrevierilor ............................................................ 22 Arhive personale şi familiale .......................................... 23 Bibliografie ...................................................................... 275 Indice de arhive ............................................................... 279 Indice antroponimic ........................................................ 290 Indice toponimic............................................................... 339 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei INTRODUCERE Cel de al II-lea volum al lucrării Arhive personale şi familiale -

Alien Invasive Species at the Romanian Black Sea Coast – Present and Perspectives

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © Décembre Vol. LIII pp. 443–467 «Grigore Antipa» 2010 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-010-0031-6 ALIEN INVASIVE SPECIES AT THE ROMANIAN BLACK SEA COAST – PRESENT AND PERSPECTIVES MARIUS SKOLKA, CRISTINA PREDA Abstract. Using literature data and personal field observations we present an overview of aquatic animal alien invasive species at the Romanian Black Sea coast, including freshwater species encountered in this area. We discuss records, pathways of introduction, origin and impact on native communities for some of these alien invasive species. In perspective, we draw attention on the potential of other alien species to become invasive in the study area. Résumé. Ce travail présente le résultat d’une synthèse effectuée en utilisant la littérature de spécialité et des observations et études personnelles concernant les espèces invasives dans la région côtière roumaine de la Mer Noire. On présente des aspects concernant les différentes catégories d’espèces invasives – stabilisées, occasionnelles et incertes – des écosystèmes marins et dulcicoles. L’origine géographique, l’impact sur les communautés d’organismes natifs, l’impact économique et les perspectives de ce phénomène sont aussi discutés. Key words: alien invasive species, Black Sea, Romania. INTRODUCTION Invasive species are one of the great problems of the modern times. Globalization, increase of commercial trades and climatic changes make invasive species a general threat for all kinds of terrestrial, freshwater or marine ecosystems (Mooney, 2005; Perrings et al., 2010). Perhaps polar areas or the deep seas are the only ecosystems not affected by this global phenomenon. Black Sea is a particular marine basin, with special hydrological characteristics, formed 10,000 years BP, when Mediterranean waters flowed to the Black Sea over the Bosporus strait.