Some Notes on the Use Oftradition in Theatre*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Prospectus 2020-21

PROSPECTUS 2020-21 Online Registration Fee Category Fee in INR General 600 EWS 550 OBC 400 SC/ST/PWD 275 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD (A Central University established by an Act of Parliament) Visitor The President of India Chief Rector The Governor of Telangana Chancellor Justice L. Narasimha Reddy Vice-Chancellor Prof. Appa Rao Podile Pro Vice-Chancellor- 1 Prof. Arun Agarwal Pro Vice-Chancellor- 2 Prof. B. Raja Shekhar University of Hyderabad Prof. C. R. Rao Road, P.O. Central University, Gachibowli, Hyderabad 500 046, Telangana, (India) University’s EPABX: 040-2313 0000 Page 2 :: PROSPECTUS: 2020-21// UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD: INDIA’S INSTITUTION OF EMINENCE WWW.UOHYD.AC.IN Page 3 :: PROSPECTUS: 2020-21// UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD: INDIA’S INSTITUTION OF EMINENCE Why University of Hyderabad? Institution of Eminence The Institution of Eminence status accorded by the Government of India to the University of Hyderabad in September 2019 is recognition of the university’s standing, ability and potential to move into the league of the world’s best institutions. With additional funding and autonomy, we are positioned to figure in the World’s 500 Best Universities in the next few years. Excellence in University System The University was previously granted the status of University with Potential for Excellence (UPE) by the University Grants Commission (UGC). The University was sanctioned a grant of Rs.30 crore under UPE Phase-1 for Interfacial Studies & Research and Holistic Development for 5 years (2002- 2007) and Rs.50 crore under the Phase-2 (2012-2016). The Advanced Centre for Research in High Energy Materials (ACRHEM) on the University campus was supported by DRDO for Research on High Energy Materials to the tune of Rs.113 crore in the Phase-3. -

Download the Complete Issue Here

Theatre for Change 1 Editorial ‘The very process of the workshop does so much for women. The process is an end in itself. For women who are not given to articulating their views, women who are not given to exploring their bodies in a creative way, for feeling good, for feeling fresh. Just doing physical and breathing exercises is a liberating experience for them. Then sharing experiences with each other and discovering that they are not insane, you know, discovering that every woman has dissatisfaction and negative feelings, touching other lives . When you come together in a space, you develop a trust, sharing with each other, enjoying just being in this space, enjoying singing and creating, out of your own experiences, your own plays’—Tripurari Sharma Theatre as process—workshopping—is an empowering activity. It encourages self- expression, develops self-confidence and communication skills, and promotes teamwork, cooperation, sharing. It is also therapeutic, helping individuals to probe within and express—share—deeply emotional experiences. Role-playing enables one to ‘enact’ something deeply personal that one is not otherwise able to express, displacing it and rendering it ‘safe’, supposedly ‘fictionalized’. In short, workshopping can be a liberatory experience. For women who, in our society especially, are not encouraged to develop an intimacy with their bodies, who are conditioned to be ashamed or uncomfortable about their physicality, the process of focusing on the body, on exercises which change one’s awareness of and relationship with and deployment of one’s body, offers an additional benefit, opening up a dimension of physicality which is normally out of bounds. -

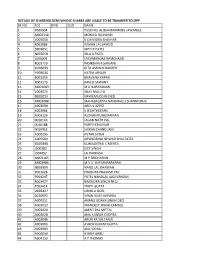

Details of Shareholders Whose Shares Are Liable to Be Transfer to Iepf Sr.No Fol Dpid Clid Name 1 Y000004 Yusufali Alibhaikarimj

DETAILS OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE SHARES ARE LIABLE TO BE TRANSFER TO IEPF SR.NO FOL DPID CLID NAME 1 Y000004 YUSUFALI ALIBHAIKARIMJEE JAWANJEE 2 M003118 MONICA DILAWARI 3 V003054 V CHANDRA SHEKHAR 4 K003086 KISHAN LAL JANGID 5 D003051 DIPTI P PATEL 6 N003058 NILA A PATEL 7 L003009 LACHMANDAS RAMCHAND 8 R003170 RASIKBHAI K SAVJANI 9 G003039 GITA ASHWIN BANKER 10 H003036 HATIM ARIAAR 11 B003056 BHAVANA KAPASI 12 R003173 RAVI D SAWANT 13 M003083 M A NARAYANAN 14 V003075 VIJAY MALLYA 15 N003055 NAYEEMUDDIN SYED 16 M003088 MAHABALAPPA NANDIHALLI SHANMUKHA 17 A003090 ABDUL AZEEZ 18 K003066 K JEGATHEESAN 19 A003126 ASOKAN KUNJURAMAN 20 0010146 JAGAN NATH PAL 21 0010188 PARTH KHAKHAR 22 0010953 SHIKAR CHAND JAIN 23 A000295 AVTAR SINGH 24 A005583 ARVINDBHAI ISHWAR BHAI PATEL 25 G003898 GUNVANTRAI C MEHTA 26 J000382 JEET SINGH 27 J004092 JAI PARKASH 28 M003185 M P SRIDHARAN 29 M003986 M.V.S. SURYANARAYANA 30 N003999 NAND LAL DHAWAN 31 P003628 PRADNYA PRAKASH PAI 32 P004247 PATEL NANDLAL JAGJIVANDAS 33 R003427 RAJENDRA SINGH NEGI 34 T003414 TRIPTI GUPTA 35 U003427 URMILA GOEL 36 0010970 KIRAN VIJAY JAIPURIA 37 A000311 ANANG UDAYA SINGH DEO 38 A003013 AMARJEET SINGH KAMBOJ 39 A003020 AMRIT PAL MITTAL 40 A003028 ANIL KUMAR CHOPRA 41 A003046 ARUN KR SULTANIA 42 A003066 ASHOK KUMAR GUPTA 43 A003983 ANIL GOYAL 44 A004030 A RAJA BABU 45 A004113 A T THOMAS 46 A004564 A. RAJA BABU 47 A004666 ANIL KUMAR LUKKAD 48 A004677 ASHA DEVI 49 A004915 ASHOK GUPTA 50 A005458 ANURAG JAIN 51 A005468 AGA REDDY VANTERU 52 B000031 BHAIRULAL GULABCHAND 53 B000049 BALMUKAND AGARWAL -

Dear Aspirant with Regard

DEAR ASPIRANT HERE WE ARE PRESENTING YOU A GENRAL AWERNESS MEGA CAPSULE FOR IBPS PO, SBI ASSOT PO , IBPS ASST AND OTHER FORTHCOMING EXAMS WE HAVE UNDERTAKEN ALL THE POSSIBLE CARE TO MAKE IT ERROR FREE SPECIAL THANKS TO THOSE WHO HAS PUT THEIR TIME TO MAKE THIS HAPPEN A IN ON LIMITED RESOURCE 1. NILOFAR 2. SWETA KHARE 3. ANKITA 4. PALLAVI BONIA 5. AMAR DAS 6. SARATH ANNAMETI 7. MAYANK BANSAL WITH REGARD PANKAJ KUMAR ( Glory At Anycost ) WE WISH YOU A BEST OF LUCK CONTENTS 1 CURRENT RATES 1 2 IMPORTANT DAYS 3 CUPS & TROPHIES 4 4 LIST OF WORLD COUNTRIES & THEIR CAPITAL 5 5 IMPORTANT CURRENCIES 9 6 ABBREVIATIONS IN NEWS 7 LISTS OF NEW UNION COUNCIL OF MINISTERS & PORTFOLIOS 13 8 NEW APPOINTMENTS 13 9 BANK PUNCHLINES 15 10 IMPORTANT POINTS OF UNION BUDGET 2012-14 16 11 BANKING TERMS 19 12 AWARDS 35 13 IMPORTANT BANKING ABBREVIATIONS 42 14 IMPORTANT BANKING TERMINOLOGY 50 15 HIGHLIGHTS OF UNION BUDGET 2014 55 16 FDI LLIMITS 56 17 INDIAS GDP FORCASTS 57 18 INDIAN RANKING IN DIFFERENT INDEXS 57 19 ABOUT : NABARD 58 20 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 58 21 OSCAR AWARD 2014 59 22 STATES, CAPITAL, GOVERNERS & CHIEF MINISTERS 62 23 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 62 23 LIST OF IMPORTANT ORGANIZATIONS INDIA & THERE HEAD 65 24 LIST OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND HEADS 66 25 FACTS ABOUT CENSUS 2011 66 26 DEFENCE & TECHNOLOGY 67 27 BOOKS & AUTHOURS 69 28 LEADER”S VISITED INIDIA 70 29 OBITUARY 71 30 ORGANISATION AND THERE HEADQUARTERS 72 31 REVOLUTIONS IN AGRICULTURE IN INDIA 72 32 IMPORTANT DAMS IN INDIA 73 33 CLASSICAL DANCES IN INDIA 73 34 NUCLEAR POWER -

INDIAN INSTITUION of TECHNICAL ARBITRATORS New No.4, Old No.36, Loganathan Colony, Mylapore Chennai – 600 004, Tamil Nadu, India Contact No

INDIAN INSTITUION OF TECHNICAL ARBITRATORS New No.4, Old No.36, Loganathan Colony, Mylapore Chennai – 600 004, Tamil Nadu, India Contact No. 098403 58060 Email: [email protected], Website: www.iitarb.org FELLOW: F – 0001 F – 0002 F – 0005 Er. M. C. Bhide Er. O.P. Goel Er. A. Sivasankaran Office Nos. 9 & 10, Gr. Floor, # B-XI / 8091, # 8, 78th Street, Sector 12, Greenland premises C.H.S, Vasant Kunj, K.K. Nagar West, Raikar Marg, New Delhi - 110 070 Chennai – 600 078 Opp. Sitaladevi Temple Road, Tel: Off. 011-26899857, 011- Phone: (O):24714605,(R):24748156, Mahim (W), Mumbai – 400 016 41783104, Mobile: 09810512775, Mobile: 09384748156, Tel: (O) 022-24442190/91/2812 (R) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 022-24361009/24314223, Fax: 022 – 2444 2746 Mobile: 9833075895 / 9892358721 Email: [email protected], [email protected] F – 0006 F – 0008 F – 0010 Er. K.D. Arcot Er. K.E. Mohan Er. M. Ulaganathan House No: U-46, No.101, Baskar Colony, No. Old 83 New 34, Plot No: 4185, Virukambakkam, Mandavelli Pakkam Street, Anna Nagar Chennai – 600 092 Mandavelipakham, Chennai – 600 040 Tel: Off: 23765250, Res: 23766039, Chennai – 600 028 Tel: 044-26215052 (O), 044- Fax: 23765560 Tel: 044 24620158, 26215052 (R) Mobile: 09445312074 Fax: 044 28291855, Mobile: 098401 26439 Email: Mobile: 09841158366 Email: [email protected] [email protected] F – 0013 F – 0015 F – 0016 Er. P.C. Pandiyan Er. S.R. Venkataraman Prof.Dr. V. Sundararajulu No.45, Car Nagar B2D, CDS Regal Palm Garden, No.146, (410 old) , Perambur # 383, Tambaram Main Road, 40th Street, TVS Avenue Chennai – 600 011 Velachery, Chennai – 42 Anna Nagar West Extn, Mobile: 098400 27434 Tel: 044-4202 1201, Chennai – 600 101 Email: Mobile: 99626 60622, Tel: Off : 26566565, Res :26544488 [email protected] Email: [email protected] Mobile: 08056098960 E-mail: [email protected] F – 0017 F – 0018 F – 0019 Er. -

20Years of Sahmat.Pdf

SAHMAT – 20 Years 1 SAHMAT 20 YEARS 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements 2 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 YEARS, 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements © SAHMAT, 2009 ISBN: 978-81-86219-90-4 Rs. 250 Cover design: Ram Rahman Printed by: Creative Advertisers & Printers New Delhi Ph: 98110 04852 Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust 29 Ferozeshah Road New Delhi 110 001 Tel: (011) 2307 0787, 2338 1276 E-mail: [email protected] www.sahmat.org SAHMAT – 20 Years 3 4 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 Years 5 Safdar Hashmi 1954–1989 Twenty years ago, on 1 January 1989, Safdar Hashmi was fatally attacked in broad daylight while performing a street play in Sahibabad, a working-class area just outside Delhi. Political activist, actor, playwright and poet, Safdar had been deeply committed, like so many young men and women of his generation, to the anti-imperialist, secular and egalitarian values that were woven into the rich fabric of the nation’s liberation struggle. Safdar moved closer to the Left, eventually joining the CPI(M), to pursue his goal of being part of a social order worthy of a free people. Tragically, it would be of the manner of his death at the hands of a politically patronised mafia that would single him out. The spontaneous, nationwide wave of revulsion, grief and resistance aroused by his brutal murder transformed him into a powerful symbol of the very values that had been sought to be crushed by his death. Such a death belongs to the revolutionary martyr. 6 PUBLICATIONS Safdar was thirty-four years old when he died. -

Bestguru.Comcarnatic Music ‐ Vocal 1978 Maharajapuram V

Name of the Artist Name of the Art / Field Awarded in Amba Sanyal (Costume Designing) Allied Theatre Arts 2008 Anant Gopal Shinde (Make‐up) Allied Theatre Arts 2003 Ashok Sagar Bhagat (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 2002 Ashok Srivastava (Make‐up) Allied Theatre Arts 1981 D. G. Godse (Scenic Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1988 Dolly Ahluwalia (Costume Design) Allied Theatre Arts 2001 G.N. Dasgupta (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 1989 Gautam Bhattacharya (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 2006 Goverdhan Panchal (Scenic Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1985 H. V. Sharma (Stagecraft) Allied Theatre Arts 2005 Kajal Ghosh (Theatre Music) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 Kamal Arora (Make‐up) Allied Theatre Arts 2009 Kamal Jain (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 2011 Kamal Tewari (Theatre Music) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 Kanishka Sen (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 1994 Khaled Choudhury (Scenic Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1986 Kuldeep Singh (Music for Theatre) Allied Theatre Arts 2009 M. S. Sathyu (Stagecraft) Allied Theatre Arts 1993 Mahendra Kumar (Scenic Design) Allied Theatre Arts 2007 Mansukh Joshi (Scenic & Light Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1997 N. Krishnamoorthy (Stagecraft) Allied Theatre Arts 1995 Nissar Allana (Stagecraft) Allied Theatre Arts 2002 R. K. Dhingra (Lighting) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 R. Paramashivan (Theatre Music) Allied Theatre Arts 2005 Robin Das (Scenic Design) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 Roshen Alkazi (Costume Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1990 Shakti Sen (Make‐up) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 Sreenivas G. Kappanna (Lighting & Stage Design) Allied Theatre Arts 2003 Suresh Bhardwaj (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 2005 Tapas Sen (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 1974 V. Ramamurthy (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 1977 Alathur S. Srinivasa Iyer Carnatic Music ‐ Vocal 1968 Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar Carnatic Music ‐ Vocal 1952 B. -

Visva-Bharati, Sangit-Bhavana Department of Rabindra Sangit, Dance & Drama CURRICULUM for UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM

Visva-Bharati, Sangit-Bhavana Department of Rabindra Sangit, Dance & Drama CURRICULUM FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM COURSE CODE: DURATION: 3 COURSE CODE SIX SEMESTER BMS YEARS NO: 41 Sl.No Course Semester Credit Marks Full Marks . 1. Core Course - CC 14 Courses I-IV 14X6=84 14X75 1050 08 Courses Practical 06 Courses Theoretical 2. Discipline Specific Elective - DSE 04 Courses V-VI 4X6=24 4X75 300 03 Courses Practical 01 Courses Theoretical 3. Generic Elective Course – GEC 04 Course I-IV 4X6=24 4X75 300 03 Courses Practical 01 Courses Theoretical 4. Skill Enhancement Compulsory Course – SECC III-IV 2X2=4 2X25 50 02 Courses Theoretical 5. Ability Enhancement Compulsory Course – AECC I-II 2X2=4 2X25 50 02 Courses Theoretical 6. Tagore Studies - TS (Foundation Course) I-II 4X2=8 2X50 100 02 Courses Theoretical Total Courses 28 Semester IV Credits 148 Marks 1850 Page 1 of 109 CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM B.MUS (HONS) COURSE AND MARKS DISTRIBUTION STRUCTURE CC DSE GEC SECC AEC TS SEM C TOTA PRA THE PRA THE PRA THE THE THE THE L C O C O C O O O O I 75 75 - - 75 - - 25 50 300 II 75 75 - - 75 - - 25 50 300 III 150 75 - - 75 - 25 - - 325 IV 150 75 - - - 75 25 - - 325 V 75 75 150 - - - - - - 300 VI 75 75 75 75 - - - - - 300 TOTA 600 450 225 75 225 75 50 50 100 1850 L Page 2 of 109 CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM B.MUS (HONS) OUTLINE OF THE COURSE STRUCTURE COURSE COURSE TYPE CREDITS MARKS HOURS PER CODE WEEK SEMESTER-I CC-1 PRACTICAL 6 75 12 CC-2 THEORETICAL 6 75 6 GEC-1 PRACTICAL 6 75 12 AECC-1 THEORETICAL 2 25 2 TS-1 THEORETICAL