Seed Development in Citrus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adirectionalcline in Mouriri Guianensis (Me Lastom at Ace Ae)

ADIRECTIONALCLINE IN MOURIRI GUIANENSIS (ME LASTOM AT ACE AE) Thomas Morley ( ;t) Abstract of specialization of the most important variable, the ovary, can be clearly identi Morphological variation in Mouriri guia- fied. The overall pattern of distribution nensis is described and analyzed throughout its range in Brazil and adjacent regions. Featu was briefly described previously (Morley, res that vary are ovary size, locule and ovule 1975, 1976); the present paper is a detai number, shape and smoothness of the leaf blade led report. and petiole length. The largest ovaries with the most ovules occur in west central Amazonia; intermediate sizes and numbers are widespread MATERIAL AND METHODS but reach the coast only between Marajó and Ceará; and the smallest ovaries with the fewest The study was carried out with locules and ovules are coastal or nearcoastal from Delta Amacuro in Venezuela to Marajó. pressed specimens borrowed from many Small ovaries also occur in coastal Alagoas and herbaria, to whose curators I am grateful. at Rio de Janeiro. Ovaries with the fewest locu The most instructive characters are those les and ovules are believed to be the most of the unripened ovary, and therefoie specialized, the result of evolution toward only flowering material was of value in decreased waste of ovules, since the fruits of all members are few-seeded. Leaf characters most cases. It was necessary that speci correlate statistically with ovule numbers. mens have a considerable excess of flo Possible origen of the distribution pattern of wers for the dissections to be made wi the species is compared in terms of present thout harm but fortunately only a few rainfall patterns and in terms of Pleistocene climatic change with associated forest refuges. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

The Origin of Alternation of Generations in Land Plants

Theoriginof alternation of generations inlandplants: afocuson matrotrophy andhexose transport Linda K.E.Graham and LeeW .Wilcox Department of Botany,University of Wisconsin, 430Lincoln Drive, Madison,WI 53706, USA (lkgraham@facsta¡.wisc .edu ) Alifehistory involving alternation of two developmentally associated, multicellular generations (sporophyteand gametophyte) is anautapomorphy of embryophytes (bryophytes + vascularplants) . Microfossil dataindicate that Mid ^Late Ordovicianland plants possessed such alifecycle, and that the originof alternationof generationspreceded this date.Molecular phylogenetic data unambiguously relate charophyceangreen algae to the ancestryof monophyletic embryophytes, and identify bryophytes as early-divergentland plants. Comparison of reproduction in charophyceans and bryophytes suggests that the followingstages occurredduring evolutionary origin of embryophytic alternation of generations: (i) originof oogamy;(ii) retention ofeggsand zygotes on the parentalthallus; (iii) originof matrotrophy (regulatedtransfer ofnutritional and morphogenetic solutes fromparental cells tothe nextgeneration); (iv)origin of a multicellularsporophyte generation ;and(v) origin of non-£ agellate, walled spores. Oogamy,egg/zygoteretention andmatrotrophy characterize at least some moderncharophyceans, and arepostulated to represent pre-adaptativefeatures inherited byembryophytes from ancestral charophyceans.Matrotrophy is hypothesizedto have preceded originof the multicellularsporophytes of plants,and to represent acritical innovation.Molecular -

The Species of Wurmbea

J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 16: 33-53 (1995) THE SPECIES OFWURMBEA(LILIACEAE) IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA Robert J. Bates Cl- State Herbarium, Botanic Gardens, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000 Abstract Nine species of Wunnbea Thunb. are recognised in South Australia. W. biglandulosa (R. Br.)Macfarlane, W. deserticola Macfarlane and W. sinora Macfarlane are recorded for the first time; Wurmbea biglandulosa ssp. flindersica, W. centralis ssp. australis, W. decumbens, W. dioica ssp. citrina, W. dioica ssp. lacunaria, W. latifolia ssp. vanessae and W. stellata are described. A key, together with notes on each species is provided. Macfarlane (1980) revised the genus for Australia. He placed Anguillaria R. Br. under Wurmbea and recognised W. dioica (R. Br.)F. Muell., W. centralis Macfarlane, W. latifolia Macfarlane and W. uniflora (R. Br.)Macfarlane as occurring in South Australia. Before this only one species, W. dioica (as Anguillaria dioica) was listed for South Australia (J.M. Black 1922, 1943). Macfarlane stated that he had seen no live material of South Australian species. The present author has made extensive field studies of taxa discussed in this paper, has cultivated most and studied herbarium material. Several trips have been made to other states to allow further comparisons to be made. For information on the nomenclatural history, general morphology, biology and ecology of Wurmbea see Macfarlane 1980. Key to the South Australian species of Wurmbea 1 Lower leaves paired (almost opposite), basal, of same shape and size 2 1: Lower leaves well separated, often of different shape and size 4 2 Leaves with serrate margins, flowers unisexual, nectaries 1 per tepal, a single band of colour... -

Liliaceae Lily Family

Liliaceae lily family While there is much compelling evidence available to divide this polyphyletic family into as many as 25 families, the older classification sensu Cronquist is retained here. Page | 1222 Many are familiar as garden ornamentals and food plants such as onion, garlic, tulip and lily. The flowers are showy and mostly regular, three-merous and with a superior ovary. Key to genera A. Leaves mostly basal. B B. Flowers orange; 8–11cm long. Hemerocallis bb. Flowers not orange, much smaller. C C. Flowers solitary. Erythronium cc. Flowers several to many. D D. Leaves linear, or, absent at flowering time. E E. Flowers in an umbel, terminal, numerous; leaves Allium absent. ee. Flowers in an open cluster, or dense raceme. F F. Leaves with white stripe on midrib; flowers Ornithogalum white, 2–8 on long peduncles. ff. Leaves green; flowers greenish, in dense Triantha racemes on very short peduncles. dd. Leaves oval to elliptic, present at flowering. G G. Flowers in an umbel, 3–6, yellow. Clintonia gg. Flowers in a one-sided raceme, white. Convallaria aa. Leaves mostly cauline. H H. Leaves in one or more whorls. I I. Leaves in numerous whorls; flowers >4cm in diameter. Lilium ii. Leaves in 1–2 whorls; flowers much smaller. J J. Leaves 3 in a single whorl; flowers white or purple. Trillium jj. Leaves in 2 whorls, or 5–9 leaves; flowers yellow, small. Medeola hh. Leaves alternate. K K. Flowers numerous in a terminal inflorescence. L L. Plants delicate, glabrous; leaves 1–2 petiolate. Maianthemum ll. Plant coarse, robust; stems pubescent; leaves many, clasping Veratrum stem. -

Ovule and Embryo Development, Apomixis and Fertilization Abdul M Chaudhury, Stuart Craig, ES Dennis and WJ Peacock

26 Ovule and embryo development, apomixis and fertilization Abdul M Chaudhury, Stuart Craig, ES Dennis and WJ Peacock Genetic analyses, particularly in Arabidopsis, have led to Figure 1 the identi®cation of mutants that de®ne different steps of ovule ontogeny, pollen stigma interaction, pollen tube growth, and fertilization. Isolation of the genes de®ned by these Micropyle mutations promises to lead to a molecular understanding of (a) these processes. Mutants have also been obtained in which Synergid processes that are normally triggered by fertilization, such as endosperm formation and initiation of seed development, Egg cell occur without fertilization. These mutants may illuminate Polar Nuclei apomixis, a process of seed development without fertilization extant in many plants. Antipodal cells Chalazi Address Female Gametophyte CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO BOX 1600, ACT 2601, Australia; e-mail:[email protected] (b) (c) Current Opinion in Plant Biology 1998, 1:26±31 Pollen tube Funiculus http://biomednet.com/elecref/1369526600100026 Integument Zygote Fusion of Current Biology Ltd ISSN 1369-5266 egg and Primary sperm nuclei Endosperm Abbreviations cell ®s fertilization-independent seed Fused Polar ®e fertilization-independent endosperm Nuclei and Sperm Double Fertilization Introduction Ovules are critical in plant sexual reproduction. They (d) (e) contain a nucellus (the site of megasporogenesis), one or two integuments that develop into the seed coat and Globular a funiculus that connects the ovule to the ovary wall. embryo Embryo The nucellar megasporangium produces meiotic cells, one of which subsequently undergoes megagametogenesis to Endosperm produce the mature female gametophyte containing eight haploid nuclei [1] (Figure 1). One of these eight nuclei becomes the egg. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

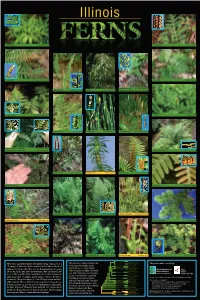

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

PLANT MORPHOLOGY: Vegetative & Reproductive

PLANT MORPHOLOGY: Vegetative & Reproductive Study of form, shape or structure of a plant and its parts Vegetative vs. reproductive morphology http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peanut_plant_NSRW.jpg Vegetative morphology http://faculty.baruch.cuny.edu/jwahlert/bio1003/images/anthophyta/peanut_cotyledon.jpg Seed = starting point of plant after fertilization; a young plant in which development is arrested and the plant is dormant. Monocotyledon vs. dicotyledon cotyledon = leaf developed at 1st node of embryo (seed leaf). “Textbook” plant http://bio1903.nicerweb.com/Locked/media/ch35/35_02AngiospermStructure.jpg Stem variation Stem variation http://www2.mcdaniel.edu/Biology/botf99/stems&leaves/barrel.jpg http://www.puc.edu/Faculty/Gilbert_Muth/art0042.jpg http://www2.mcdaniel.edu/Biology/botf99/stems&leaves/xstawb.gif http://biology.uwsp.edu/courses/botlab/images/1854$.jpg Vegetative morphology Leaf variation Leaf variation Leaf variation Vegetative morphology If the primary root persists, it is called a “true root” and may take the following forms: taproot = single main root (descends vertically) with small lateral roots. fibrous roots = many divided roots of +/- equal size & thickness. http://oregonstate.edu/dept/nursery-weeds/weedspeciespage/OXALIS/oxalis_taproot.jpg adventitious roots = roots that originate from stem (or leaf tissue) rather than from the true root. All roots on monocots are adventitious. (e.g., corn and other grasses). http://plant-disease.ippc.orst.edu/plant_images/StrawberryRootLesion.JPG Root variation http://bio1903.nicerweb.com/Locked/media/ch35/35_04RootDiversity.jpg Flower variation http://130.54.82.4/members/Okuyama/yudai_e.htm Reproductive morphology: flower Yuan Yaowu Flower parts pedicel receptacle sepals petals Yuan Yaowu Flower parts Pedicel = (Latin: ped “foot”) stalk of a flower. -

Vegetative Vs. Reproductive Morphology

Today’s lecture: plant morphology Vegetative vs. reproductive morphology Vegetative morphology Growth, development, photosynthesis, support Not involved in sexual reproduction Reproductive morphology Sexual reproduction Vegetative morphology: seeds Seed = a dormant young plant in which development is arrested. Cotyledon (seed leaf) = leaf developed at the first node of the embryonic stem; present in the seed prior to germination. Vegetative morphology: roots Water and mineral uptake radicle primary roots stem secondary roots taproot fibrous roots adventitious roots Vegetative morphology: roots Modified roots Symbiosis/parasitism Food storage stem secondary roots Increase nutrient Allow dormancy adventitious roots availability Facilitate vegetative spread Vegetative morphology: stems plumule primary shoot Support, vertical elongation apical bud node internode leaf lateral (axillary) bud lateral shoot stipule Vegetative morphology: stems Vascular tissue = specialized cells transporting water and nutrients Secondary growth = vascular cell division, resulting in increased girth Vegetative morphology: stems Secondary growth = vascular cell division, resulting in increased girth Vegetative morphology: stems Modified stems Asexual (vegetative) reproduction Stolon: above ground Rhizome: below ground Stems elongating laterally, producing adventitious roots and lateral shoots Vegetative morphology: stems Modified stems Food storage Bulb: leaves are storage organs Corm: stem is storage organ Stems not elongating, packed with carbohydrates Vegetative -

Ovary Structure of the Genus Gyrogyne (Gesneriaceae, Epithemateae)

CSIRO PUBLISHING www.publish.csiro.au/journals/asb Australian Systematic Botany 16, 629–632 Ovary structure of the genus Gyrogyne (Gesneriaceae, Epithemateae) Yin-Zheng Wang Laboratory of Systematic & Evolutionary Botany and Herbarium, Institute of Botany, The Chinese Academy of Sciences, 20 Nanxincun, Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The anatomical re-investigation of the ovary in the holotype of Gyrogyne subaequifolia W.T.Wang is carried out in order to clarify the ovarian structure of the genus Gyrogyne W.T.Wang (Gesneriaceae), a seemingly unusual ovarian structure according to its original description. The present anatomical re-investigation reveals that the ovary is, in fact, bilocular with a swollen axile placenta in the centre, that is, the median area of the membranous septum. The ovarian structure of G. subaequifolia shows, thus, a common feature frequently observed in the ovaries of Gesneriaceae rather than a unique ovarian characteristic that contributes to the family Gesneriaceae. The systematic placement of Gyrogyne and the relationship between Gyrogyne and allies are discussed. SB03004 NoY.- tesZ. onWang t he ovary structur e of Gy rogyne Introduction Results The monospecific genus Gyrogyne W. T. Wa n g The transections at the basal part of the ovary are not clear, (Gesneriaceae) endemic to China was established on the for the flower is very depressed (not shown). Upward from basis of the only species, G. subaequifolia W. T. Wa n g , the lower part, the structure of the ovary gradually becomes described at the same time (Wang 1981). In the original visible. -

Plant Evolution and Diversity B. Importance of Plants C. Where Do Plants Fit, Evolutionarily? What Are the Defining Traits of Pl

Plant Evolution and Diversity Reading: Chap. 30 A. Plants: fundamentals I. What is a plant? What does it do? A. Basic structure and function B. Why are plants important? - Photosynthesize C. What are plants, evolutionarily? -CO2 uptake D. Problems of living on land -O2 release II. Overview of major plant taxa - Water loss A. Bryophytes (seedless, nonvascular) - Water and nutrient uptake B. Pterophytes (seedless, vascular) C. Gymnosperms (seeds, vascular) -Grow D. Angiosperms (seeds, vascular, and flowers+fruits) Where? Which directions? II. Major evolutionary trends - Reproduce A. Vascular tissue, leaves, & roots B. Fertilization without water: pollen C. Dispersal: from spores to bare seeds to seeds in fruits D. Life cycles Æ reduction of gametophyte, dominance of sporophyte Fig. 1.10, Raven et al. B. Importance of plants C. Where do plants fit, evolutionarily? 1. Food – agriculture, ecosystems 2. Habitat 3. Fuel and fiber 4. Medicines 5. Ecosystem services How are protists related to higher plants? Algae are eukaryotic photosynthetic organisms that are not plants. Relationship to the protists What are the defining traits of plants? - Multicellular, eukaryotic, photosynthetic autotrophs - Cell chemistry: - Chlorophyll a and b - Cell walls of cellulose (plus other polymers) - Starch as a storage polymer - Most similar to some Chlorophyta: Charophyceans Fig. 29.8 Points 1. Photosynthetic protists are spread throughout many groups. 2. Plants are most closely related to the green algae, in particular, to the Charophyceans. Coleochaete 3. -

Investigation Into the Genetic Basis of Increased Locule Number in Heirloom Tomato Cultivars

Investigation Into The Genetic Basis Of Increased Locule Number In Heirloom Tomato Cultivars Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Paton, Andrew James Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 11:38:21 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/632842 INVESTIGATION INTO THE GENETIC BASIS OF INCREASED LOCULE NUMBER IN HEIRLOOM TOMATO CULTIVARS By ANDREW JAMES PATON ____________________ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors degree With Honors in Molecular and Cellular Biology THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA M A Y 2 0 1 9 Approved by: ____________________________ Dr. Frans Tax Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology Abstract Tomatoes are an important crop for many types of foods and can be easily preserved, making them an attractive candidate for selective genetic modification. One trait that could be improved upon is locule number, which can increase the practical edible mass of each tomato. To identify genes that may be responsible for this phenotype, we PCR-amplified, gel-imaged, and sequenced candidate genes in several heirloom tomato cultivars that naturally exhibit multiple locules. These candidate genes were selected from genes involved in the CLV-WUS feedback mechanism that act to control proliferation of apical meristems, which directly impact the characteristics of fruit.