Mukul Dey: an Autobiographically Modern Indian Artist1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 9 | 2014 Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Gl

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 9 | 2014 Imagining Bangladesh: Contested Narratives Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Globalization Lala Rukh Selim Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3725 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.3725 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Lala Rukh Selim, “Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Globalization”, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], 9 | 2014, Online since 22 July 2014, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3725 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.3725 This text was automatically generated on 21 September 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Gl... 1 Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Globalization Lala Rukh Selim Introduction 1 The art of Bangladesh embodies the social and political changes that have transformed the country/region through history. What was once a united state of Bengal is now divided into two parts, the sovereign country of Bangladesh and the state of West Bengal in India. The predominant religion in Bangladesh is Islam and that of West Bengal is Hinduism. Throughout history, ideas and identifications of certain elements of culture as ‘tradition’ have played an important role in the construction of notions of identity in this region, where multiple cultures continue to meet. The celebrated pedagogue, writer and artist K. -

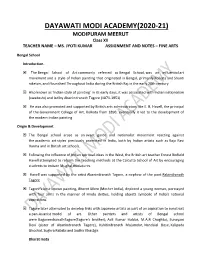

DAYAWATI MODI ACADEMY(2020-21) MODIPURAM MEERUT Class XII TEACHER NAME – MS

DAYAWATI MODI ACADEMY(2020-21) MODIPURAM MEERUT Class XII TEACHER NAME – MS. JYOTI KUMAR ASSIGNMENT AND NOTES – FINE ARTS Bengal School Introduction- The Bengal School of Art commonly referred as Bengal School, was an influential art movement and a style of Indian painting that originated in Bengal, primarily Kolkata and Shanti niketan, and flourished Throughout India during the British Raj in the early 20th century. Also known as 'Indian style of painting' in its early days, it was associated with Indian nationalism (swadeshi) and led by Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951) He was also promoted and supported by British arts administrators like E. B. Havell, the principal of the Government College of Art, Kolkata from 1896; eventually it led to the development of the modern Indian painting Origin & Development The Bengal school arose as an avant garde and nationalist movement reacting against the academic art styles previously promoted in India, both by Indian artists such as Raja Ravi Varma and in British art schools. Following the influence of Indian spiritual ideas in the West, the British art teacher Ernest Binfield Havell attempted to reform the teaching methods at the Calcutta School of Art by encouraging students to imitate Mughal miniatures. Havell was supported by the artist Abanindranath Tagore, a nephew of the poet Rabindranath Tagore Tagore's best-known painting, Bharat Mata (Mother India), depicted a young woman, portrayed with four arms in the manner of Hindu deities, holding objects symbolic of India's national aspirations. Tagore later attempted to develop links with Japanese artists as part of an aspiration to construct a pan-Asianist model of art. -

Dakghar: Notes Towards Isolation and Recognition

Dakghar: Notes Towards Isolation and Recognition Landings (Natasha Ginwala and Vivian Ziherl) 2 Dakghar: Notes Toward hood and of letter-writing Isolation and Recognition as a visual practice. evokes a multi-character read- ing of Rabindranath Tagore’s The allegorical plot of Dakghar play Dakghar / The Post centers upon the child Office (1912). Archival material protagonist Amal who suffers and artistic works perform from an incurable malady and as symbolic protagonists weav- is thus enclosed in the ‘pro- ing together correspondences tection’ of a village courtyard. between Tagore, his collabora- Amal is compelled to cultivate tors, and the rural as a stage a projected imagination of of modern encounters. the outside world upon the news that a post office is to This research presentation be built in his village. This undertakes figural readings anticipated event provokes of the play, tracing its reception a horizon of desire in which the in Europe while also casting a nearby village, the King’s broader backdrop of Tagore’s impending visit and a phantas- pedagogy of art as life-practice mal life become conflated at the rural campus of Santi- terrains. Written against the niektan (est. 1901), his travels backdrop of anti-colonial through South East Asia critique, Dakghar ultimately pursuing ‘Asian Modernity’ considers the place of the soul as a force of civilizational con- within the narration of history. tiguity and alliance-building, as well as his collective experi- Through these dynamic ments in Rural Reconstruction tensions of worldly encounter and development of the and subjective alienation, handicrafts at Sriniketan the multiple status of Tagore (1921-41). -

Eve LOH KAZUHARA Ruptures and Continuity in Pan-Asianism: New Insights Into India-Japan Artistic Exchanges in the First Half of the Twentieth Century

Eve LOH KAZUHARA Ruptures and Continuity in Pan-Asianism: New Insights into India-Japan Artistic Exchanges in the first half of the Twentieth Century PhD student, National University of Singapore, Singapore. [email protected] In the first half of the twentieth century, India and Japan embarked on a series of intellectual and artistic exchanges from 1901 to the 1930s. The beginning of these exchanges is often recounted in the meeting of Okakura Kakuzō (1863–1913) and Rabindranath Tagore (1886–1941) and revolves around their successors, namely Yokoyama Taikan, Hishida Shunsō and Abanindranath Tagore. The narrative histories of these personalities overshadow other Japanese artists and their activities in India. In this paper, I propose to consider these other artists and their place in the Japan-Bengal exchanges. The discussion will consider the biographic narratives of these artists and centreon their activities and artworks, primarily in seeing how they differed from the afore-mentioned artists. In my view, the artistic affiliation of these artists pre-India, together with their ideological distance from Okakura’s Pan- Asianism, influenced their activities and reception of their work post-India. One of the motivations behind my paper was trying to situatethe artists who went to India, particularly those who have been mentioned albeit brieflyin both Japanese and non- Japanese sources. There were also instances of encountering works on India and Indian themes by nihonga (Japanese-style painting) artists and that made me wonder if there was a deeper or wider connection to other artists. My initial task was to collate as much information on the Japanese artists’ visits asthere was no detailed listing anywhere. -

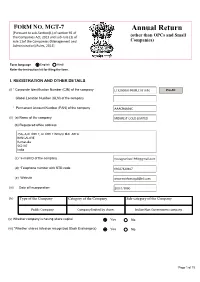

Annual Return

FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of (other than OPCs and Small rule 11of the Companies (Management and Companies) Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company (ii) (a) Name of the company (b) Registered office address (c) *e-mail ID of the company (d) *Telephone number with STD code (e) Website (iii) Date of Incorporation (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM (b) Due date of AGM 30/09/2021 (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No (f) Specify the reasons for not holding the same II. PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF THE COMPANY *Number of business activities 1 S.No Main Description of Main Activity group Business Description of Business Activity % of turnover Activity Activity of the group code Code company B B4 III. -

The Silver Series - 3

DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 THE SILVER SERIES EDITION 3 6 - 10 JULY 2020 10% SALE PROCEEDS TO 1 DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 THE SILVER SERIES EDITION 3 100 ARTISTS ² 100 WORKS Modern and Contemporary Indian Art 6 - 10 JULY 2020 FIXED-PRICE ONLINE SALE The Silver Series is DAG’s initiative towards raising funds for charity through its fixed-price online sales For further information please contact us at [email protected] 1 DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 FROM ASHISH ANAND’S DESK Hundreds of great artists have marked every decade of the twentieth century, which is why I have always been surprised at the invisibility of so many of our masters. Painters, sculptors, printmakers, teachers, they have made a name for themselves, but in the absence of their work being shown nationally—rather than regionally, as has been the norm—many have remained outside mainstream discourse. At DAG, it has been our effort to ensure their rediscovery and recognition, something we continue to do with our Silver Series, fixed-price online sales. The outstanding success of the first two editions is an indicator that art-lovers also have an appreciation for lesser-known names, as well as those whose works do not appear frequently in the market. Our endeavour with every edition will be to continue to surprise you with the mix of artists and the quality of their work. I hope the additions in this edition will bring you joy. If you miss any favourites, I assure you that you will find them in subsequent editions. -

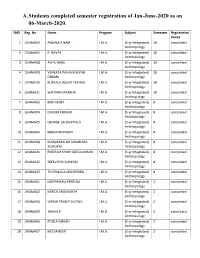

A. Students Completed Semester Registration of Jan-June-2020 As on 06-March-2020

A. Students completed semester registration of Jan-June-2020 as on 06-March-2020. SNO Reg. No Name Program Subject Semester Registration Status 1 15IAMA03 ANJANA R NAIR I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 10 completed Anthropology 2 15IAMA05 P. NAVYA I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 10 completed Anthropology 3 15IAMA08 AKHIL BABU I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 10 completed Anthropology 4 15IAMA09 VENKATA PAVAN KALYAN I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 10 completed OBBANI Anthropology 5 15IAMA10 KUKKALA BLESSY TEJASWI I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 10 completed Anthropology 6 15IAMA11 SURTHANI PRABHU I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 10 completed Anthropology 7 16IAMA03 BIBIN BABY I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 8 completed Anthropology 8 16IAMA04 DHEERAJ SRIGIRI I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 8 completed Anthropology 9 16IAMA05 GEORGE LALRUATFELA I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 8 completed Anthropology 10 16IAMA06 KIRAN KRISHNAN I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 8 completed Anthropology 11 16IAMA08 MARUPAKA SAI SHANKARA I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 8 completed SUMUKHI Anthropology 12 16IAMA10 REBEKAH SHINY GOGULAMUDI I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 8 completed Anthropology 13 16IAMA12 SREEVIDYA SUNKARI I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 8 completed Anthropology 14 16IAMA13 THUPAKULA MAHENDRA I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 8 completed Anthropology 15 19IAMA01 DEEPSHIKHA PENTOM I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 2 completed Anthropology 16 19IAMA02 KARIDE SHASHANTH I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 2 completed Anthropology 17 19IAMA03 YEPURI PRINCY SUJITHA I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 2 completed Anthropology 18 19IAMA05 JISHNU P I.M.A. (5-yr Integrated) 2 completed Anthropology 19 19IAMA06 POOLA DINESH I.M.A. -

NANDALAL BOSE the Doyen of Indian Art DINKAR KOWSHIK

NANDALAL BOSE The doyen of Indian art DINKAR KOWSHIK Contents Forebears and Parents School and College Education Nandalal enters the Magic Circle Early Laurels Discovery of Indian Art At Ajanta Okakura The Poet and the Painter Nandalal and Coomaraswamy Interim Ethical Moorings Far Eastern Voyage Wall Paintings Architecture & Museum Notes on His Paintings Art for the Community Depression Artist of the Indian National Congress A Humane and Kindly Being Nandalal and His Students Nandalal’s Views on Art Gandhiji’s Visit —1945 Admirers and Critics Evening Years I am indebted to the following scholars, authors, colleagues and relatives of Acharya Nandalal Bose for their assistance in assembling material for this book. Their writings and information given during personal interviews have been most helpful: Sri Banabehari Gosh, Sri Biswarup Bose, Sm. Gouri Bhanja, Sm. Jamuna Sen, Sri Kanai Samanta, Sri K.G. Subramanyan, Sri Panchanan Mandal, Sri Rabi Paul, Sri Sanat Bagchi, Sm. Uma Das Gupta, Sm. Arnita Sen. I am grateful to Sri Sumitendranath Tagore for his permission to reproduce Acharya Nandalal’s portrait by Abanindranath Tagore on the cover. I thank Dr. L.P. Sihare, Director, National Gallery of Modern Art, for allowing me to use photographs of Acharya Nandalal’s paintings from the collections in the National Gallery. I record my special gratitude to Sm. Jaya Appasamy, who went through the script, edited it and brought it to its present shape. Santiniketan 28 November 1983 DINKAR KOWSHIK Forebears and Parents Madho, Basavan, Govardhan, Bishandas, Mansur, Mukund and Manohar are some of the artists who worked in the imperial ateliers of Akbar and Jehangir. -

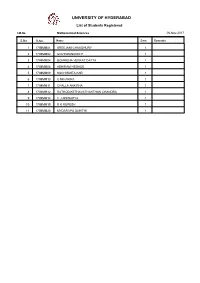

List of Students Onroles

UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences 06-Nov-2017 S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 17IMMM01 SREEJANI CHAUDHURY 1 2 17IMMM02 GOVINDANUNNI P 1 3 17IMMM04 BOMMENA VENKAT DATTA 1 4 17IMMM06 ABHIRAM HEGADE 1 5 17IMMM08 SUCHISMITA KAR 1 6 17IMMM10 G NIHARIKA 1 7 17IMMM11 CHALLA ANKITHA 1 8 17IMMM12 RATHOD KETHAVATH MITHUN CHANDRA 1 9 17IMMM14 C J AISWARYA 1 10 17IMMM19 R K RUPESH 1 11 17IMMM20 MYDARAPU SAHITHI 1 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences 06-Nov-2017 S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 16IMMM01 ADITYA SARMA PHUKON 3 2 16IMMM08 JAY PRADHAN 3 3 16IMMM09 KODAMANCHILI SAI PAVAN KUMAR 3 4 16IMMM12 NABARUN SAHA 3 5 16IMMM15 PANDI SRIDINESH 3 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences 06-Nov-2017 S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 15IMMM01 KANIKIREDDY NAGAPOOJITHA 5 2 15IMMM05 ALAPATI CHAITANYA LAKSHMI 5 3 15IMMM07 K TITIKSHA SRINIVAS 5 4 15IMMM09 GOUTHA SAMYUSHA 5 5 15IMMM15 SHILPI MANDAL 5 6 15IMMM17 TAMARANA Y V L PRASANTH 5 7 15IMMM18 ALAAP HASAN 5 8 15IMMM19 SAI KRISHNA AMANCHI 5 9 15IMMM21 TADINADA SRI HARSHITHA 5 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences 06-Nov-2017 S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 14ILMB18 MANUPRASAD E 7 2 14IMMM01 P R NANDA KUMARI 7 3 14IMMM03 RUDDARRAJU AMRUTHA 7 4 14IMMM13 BODA SWAROOPA 7 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. -

1954 to 1959

Gallantry Awards And Civilian Awards || Awards In India || Sports & Literature Awards || 1954 to 1959 Grants are the badge of regard and honor consulted to the individuals with important accomplishments. The rundown of grants in India is tremendous as individuals have been checking incredible accomplishments in different fields. The significant classifications of Awards in India are: 1. Civilian Awards 2. Gallantry Awards This article is about the rundown of grants in India for different fields of accomplishments. This is a significant point for applicants showing up for UPSC and other government tests. Table of Contents: 1. Civilian Awards 2. List of Civilian Awards & Awardees 2020 3. List of Civilian Awards & Awardees 2019 4. Gallantry Awards 5. List of Gallantry Awards & Awardees 2020 6. List of Gallantry Awards & Awardees 2019 https://gkduniya.in/ Civilian Awards Civilian Awards are deliberated to individuals with exceptional accomplishments in their field of work. These honors are introduced to the individual beneficiaries by the President of India on Republic Day. The beginning year of these Civilian honors is 1954. Civilian Awards are arranged by the level of honor. The Civilian honors presented are: 1. Bharat Ratna-first level of honor 2. the second level of honor - Padma Vibhushan 3. Padma Bhushan-third level of honor 4. Padma Shri-fourth level of honor Bharat Ratna Bharat Ratna is the most noteworthy Civilian Award in India. This honor is presented for accomplishments in the field of Science, Literature, Arts, and Public Services. In 2013, sports were additionally recalled for this honor classification. The honor has the state of Peepal leaf and is bronze-conditioned. -

ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Babu K

PARIPEX - INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH | Volume-9 | Issue-3 | March - 2020 | PRINT ISSN No. 2250 - 1991 | DOI : 10.36106/paripex ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Arts KEY WORDS: Modernization, VARIOUS CRITICAL FACTORS REQUIRED CARE Florence School, Salon De Refuses, FOR MAINTENANCE OF MODERNIZATION ON Luvre, Bauhaus, Colonial Period, E B Havell, Tagore, Stella Karmrisch, N S ART EDUCATION IN INDIA Bendre, College Of Fine Arts, Cholamandhalam, Aesthetics. Babu K Artist Modernization process took place on Art Education in India was a continuation of similar processes took place in various venues all over the world, beginning from the Florentine School which supported many major artists like Michelangelo. th CT There is a straight clear path definable from 15 century developments through Salon de Refuses in Paris, and establishments of various schools all over the World to modern developments in India. In India British promoted art production in the lines of their tastes and educated Indian Artists productions to suits their tastes. In the past there was several developments lead promotion of an art education system which has roots with Bauhaus school of Europe. Starting ABSTRA from initiation of Kalabhavana by Tagore, also we fell in to the line of progress. It requires special care to keep the attitude of modernization while evaluating all different affecting faculties including changes in our walks of lives. INTRODUCTION: revelations to its beneficiaries at Kalabhawana. It was an Application of a systematic approach on Art Education was experimental activity but followed by introduction of many art begun to be followed since establishment of Florentine historians like Charls Fabri (Note-5).