2016 23Rdps 001-284.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Surveillance of Ethiopian Women Athletes for Capital

Tracking Work from the Wrist: The Surveillance of Ethiopian Women Athletes for Capital Hannah Borenstein Duke University [email protected] Abstract This essay explores the proliferating uses of GPS watches among women athletes in Ethiopia. Aspiring and successful long-distance runners have been using GPS watches in increasing numbers over the past several years, rendering their training trackable for themselves, partners, coaches, sponsors, and agents located in the Global North. This essay explores how the transnational dimensions of the athletics industry renders their training data profitable to systems of capitalist accumulation while exploring how athletes put the emerging technologies to work to aid in their pursuit of succeeding in the sport and work of running. New Metrics In 2013, when I was first living with young sub-elite athletes at a training camp in Ethiopia, nearly all runners wore basic digital watches. Casio was the leading brand, but any watch that had a time setting, a few alarms, and, crucially, the start-stop function, was a critical instrument for long-distance running aspirants. Watches that could record splits—different intervals of training—were coveted, but by no means the norm. Thus, the metric that everyone used to discuss training was time. Recovery runs were spoken about in terms of hours run: “one- Borenstein, Hannah. 2021. “Tracking Work from the Wrist: Surveillance of Ethiopian Women Athletes for Capital.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 7 (1): 1–20. http://www.catalystjournal.org | ISSN: 2380-3312 © Hannah Borenstein, 2021 | Licensed to the Catalyst Project under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license Special Section: Self-Tracking, Embodied Differences, and the Politics and Ethics of Health twenty.” Speed sessions were broken down into minutes: “we did three minutes by eight with sixty seconds rest.” Athletes knew that this would need to be converted to kilometers for their performances, but conversations about training were discussed in terms of time. -

Kanhaiya Kumar Singh a PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS STUDY of ETHIOPIAN FOOTBALL DURING 2008-2018 Dr. Kanhaiya Kumar Singh, Assistant

International Journal of Physical Education, Health and Social Science (IJPEHSS) ISSN: 2278 – 716X www.ijpehss.org Vol. 7, Issue 1, (2018) Peer Reviewed, Indexed and UGC Approved Journal (48531) Impact Factor 5.02 A PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS STUDY OF ETHIOPIAN FOOTBALL DURING 2008-2018 Dr. Kanhaiya Kumar Singh, Assistant Professor Sports Academy, Bahirdar University, Ethiopia ABSTRACT The purpose of the study was to analyse the overall journey of Ethiopian National football at international level as well domestic level in last decade. In order to analyse the fact observation method has been used to collect data. Finding of the study reflects that Ethiopian national football is losing its position and credibility continuously in the last decade. It might be happened due to some socio-political issue the Ethiopian football federation, moreover for FIFA2014 Ethiopian national football team scored total 12 goals and conceded 21 goals and reached up to first qualifying round then Nigeria went to FIFA World Cup 2014. Further for FIFA 2018 (Russia), Ethiopian National Team reached up to second qualifying round and eliminated by COGO. Ethiopian Domestic football leagues are Premier League, Higher League and National League conducted every year, it is important to note that 70% winning position in Premier League went to one team i.e., Saint Gorge FC and rest 30% goes to other 15 playing teams. It clearly shows the lack of competitive balance in the most famous domestic league of a country. At the continent level in Champions League Country best domestic team scored 18th Rank out of 59 teams. In Super League (Winner of Champions League v/s Winners of Confederation Cup) Ethiopian football team has not seen anywhere. -

Olympic Charter

OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 © International Olympic Committee Château de Vidy – C.P. 356 – CH-1007 Lausanne/Switzerland Tel. + 41 21 621 61 11 – Fax + 41 21 621 62 16 www.olympic.org Published by the International Olympic Committee – July 2020 All rights reserved. Printing by DidWeDo S.à.r.l., Lausanne, Switzerland Printed in Switzerland Table of Contents Abbreviations used within the Olympic Movement ...................................................................8 Introduction to the Olympic Charter............................................................................................9 Preamble ......................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Principles of Olympism .......................................................................................11 Chapter 1 The Olympic Movement ............................................................................................. 15 1 Composition and general organisation of the Olympic Movement . 15 2 Mission and role of the IOC* ............................................................................................ 16 Bye-law to Rule 2 . 18 3 Recognition by the IOC .................................................................................................... 18 4 Olympic Congress* ........................................................................................................... 19 Bye-law to Rule 4 -

The Podium for Holland, the Plush Bench for Belgium

The Podium for Holland, The Plush Bench for Belgium The Low Countries and the Olympic Games 58 [ h a n s v a n d e w e g h e ] Dutch Inge de Bruin wins The Netherlands is certain to win its hundredth gold medal at the London 2012 gold. Freestyle, 50m. Olympics. Whether the Belgians will be able to celebrate winning gold medal Athens, 2004. number 43 remains to be seen, but that is not Belgium’s core business: Bel- gium has the distinction of being the only country to have provided two presi- dents of the International Olympic Committee. The Netherlands initially did better in the IOC membership competition, too. Baron Fritz van Tuijll van Serooskerken was the first IOC representative from the Low Countries, though he was not a member right from the start; this Dutch nobleman joined the International Olympic Committee in 1898, two years after its formation, to become the first Dutch IOC member. Baron Van Tuijll is still a great name in Dutch sporting history; in 1912 he founded a Dutch branch of the Olympic Movement and became its first president. However, it was not long before Belgium caught up. There were no Belgians among the 13 men – even today, women members are still few and far between – who made up the first International Olympic Committee in 1894, but thanks to the efforts of Count Henri de Baillet-Latour, who joined the IOC in 1903, the Olympic Movement became the key international point of reference for sport in the Catholic south. The Belgian Olympic Committee was formed three years later – a year af- ter Belgium, thanks to the efforts of King Leopold II, had played host to the prestigious Olympic Congress. -

2020 Len European Water Polo Championships

2020 LEN EUROPEAN WATER POLO CHAMPIONSHIPS PAST AND PRESENT RESULTS Cover photo: The Piscines Bernat Picornell, Barcelona was the home of the European Water Polo Championships 2018. Situated high up on Montjuic, it made a picturesque scene by night. This photo was taken at the Opening Ceremony (Photo: Giorgio Scala/Deepbluemedia/Insidefoto) Unless otherwise stated, all photos in this book were taken at the 2018 European Championships in Barcelona 2 BUDAPEST 2020 EUROPEAN WATER POLO CHAMPIONSHIPS PAST AND PRESENT RESULTS The silver, gold and bronze medals (left to right) presented at the 2018 European Championships (Photo: Giorgio Scala/Deepbluemedia/Insidefoto) CONTENTS: European Water Polo Results – Men 1926 – 2018 4 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Leading Scorers 2018 59 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Top Scorers 60 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Medal Table 61 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Referees 63 European Water Polo Club Competitions – Men 69 European Water Polo Results – Women 1985 -2018 72 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Leading Scorers 2018 95 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Top Scorers 96 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Medal Table 97 Most Gold Medals won at European Championships by Individuals 98 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Referees 100 European Water Polo Club Competitions – Women 104 Country By Country- Finishing 106 LEN Europa Cup 109 World Water Polo Championships 112 Olympic Water Polo Results 118 2 3 EUROPEAN WATER POLO RESULTS MEN 1926-2020 -

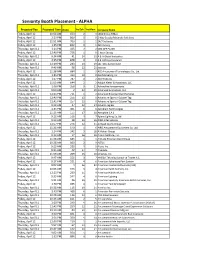

Seniority Rank with Extimated Times.Xlsx

Seniority Booth Placement ‐ ALPHA Projected Day Projected Time Order Yrs Exh Yrs Mem Company Name Friday, April 12 10:54 AM 633 2 3 1602 Group TiMax Friday, April 12 2:10 PM 860 002 Way Supply/Motorola Solutions Friday, April 12 11:51 AM 700 1 2 24/7 Software Friday, April 12 1:45 PM 832 0 1 360 Karting Thursday, April 11 3:14 PM 435 7 2 50% OFF PLUSH Friday, April 12 12:40 PM 756 105‐hour Energy Thursday, April 11 9:34 AM 41 24 10 A & A Global Industries Friday, April 12 2:25 PM 878 0 0 A.E. Jeffreys Insurance Thursday, April 11 12:29 PM 243 13 19 abc rides Switzerland Thursday, April 11 9:49 AM 58 22 25 accesso Friday, April 12 11:38 AM 684 1 3 ACE Amusement Technologies Co., Ltd. Thursday, April 11 1:46 PM 333 10 8 Ace Marketing Inc. Friday, April 12 1:07 PM 787 0 2 ADJ Products Friday, April 12 11:03 AM 644 2 2 Adolph Kiefer & Associates, LLC Thursday, April 11 2:08 PM 358 9 11 Adrenaline Amusements Thursday, April 11 9:00 AM 2 33 29 Advanced Animations, LLC Friday, April 12 12:01 PM 711 1 2 Advanced Entertainment Services Thursday, April 11 12:40 PM 256 13 0 Adventure Sports HQ Laser Tag Thursday, April 11 12:41 PM 257 13 0 Adventure Sports HQ Laser Tag Thursday, April 11 9:39 AM 47 23 24 Adventureglass Thursday, April 11 2:45 PM 401 8 8 Aerodium Technologies Thursday, April 11 11:13 AM 155 17 18 Aerophile S.A.S Friday, April 12 9:12 AM 516 4 7 Aglare Lighting Co.,ltd Thursday, April 11 9:23 AM 28 25 26 AIMS International Thursday, April 11 12:57 PM 276 12 11 Airhead Sports Group Friday, April 12 11:26 AM 670 1 6 AIRO Amusement Equipment Co. -

Attractions Management News 7Th August 2019 Issue

Find great staff™ Jobs start on page 27 MANAGEMENT NEWS 7 AUGUST 2019 ISSUE 136 www.attractionsmanagement.com Universal unveils Epic Universe plans Universal has finally confirmed plans for its fourth gate in Orlando, officially announcing its Epic Universe theme park. Announced at an event held at the Orange County Convention Center in Orlando, Epic Universe will be the latest addition to Florida's lucrative theme park sector and has been touted as "an entirely new level of experience that forever changes theme park entertainment". "Our new park represents the single- largest investment Comcast has made ■■The development almost doubles in its theme park business and in Florida Universal's theme park presence in Orlando overall,” said Brian Roberts, Comcast chair and CEO. "It reflects the tremendous restaurants and more. The development excitement we have for the future of will nearly double Universal’s total our theme park business and for our available space in central Florida. entire company’s future in Florida." "Our vision for Epic Universe is While no specific details have been historic," said Tom Williams, chair and revealed about what IPs will feature in CEO for Universal Parks and Resorts. This is the single largest the park, Universal did confirm that the "It will become the most immersive and investment Comcast has made 3sq km (1.2sq m) site would feature innovative theme park we've ever created." in its theme park business an entertainment centre, hotels, shops, MORE: http://lei.sr/J5J7j_T Brian Roberts FINANCIALS NEW AUDIENCES -

Spring 2016 Newsletter

Fast Track Spring 2016 Acro Team Canada at In this Issue: Worlds in China Acro Team Canada at 2 For fourteen young acrobatic gymnasts Worlds in China from Oakville Gymnastics Club it was a FAQ & Answers 4 dream come true and a trip of a lifetime. “Faster, Higher, Stronger” Between March 19th and March 28th, The 2016 2016, these athletes travelled over 8000 Summer Olympics 31 km across the world to Putian, China to compete in the 9th Acrobatic Gymnastics Program Updates World Age Group Competitions. Cont. page 2 Acro Group 5 Men’s Artistic 9 Tumbling 15 FAQs & Answers Woman’s Artistic 21 Why does OGC have both recreation Recreational 28 and competitive gymnastics programs? Meet the Gymnasts! What competitive gymnastics programs are available and how does my child Acro Athlete Profile 6 get involved? - Tessa Chriricosta - Danilela Mendoza & What are ‘volunteer meet hours’ and - Jenelle Coutinho as a ‘tumbling’ parent, do I need to Aidan Horsman, MAG 9 participate in an Acrobatics Meet? Helen Dong, Tumbling 15 Cont. page 4 Leona Liao, WAG 21 Health & Nutrition “Faster, Higher, Stronger” The 2016 Summer Olympics Clinic Corner 35 After a long four year wait, it is time for the Summer Olympic Games! Cont. page 31 FAST TRACK FALL 2015 Unquestionably, this is one of the things that sets them apart: their ability to keep going through the difficult times and continue striving for excellence. Certainly the most remarkable Acro Team Canada at Worlds in China example of this was observed in the days before the team was set to leave for China. -

Jonathan C. Got Berlin Perspectives on Architecture 1 Olympiastadion

Jonathan C. Got Berlin Perspectives on Architecture Olympiastadion – Germania and Beyond My personal interest with the Olymiastadion began the first week I arrived in Berlin. Having only heard about Adolf Hitler’s plans for a European Capital from documentaries and seen pictures of Jesse Owen’s legendary victories in the ill-timed 1936 Summer Olympics, I decided to make a visit myself. As soon as I saw the heavy stone colonnade from the car park I knew it could only have been built for one purpose – propaganda for the Third Reich beyond Germania. Remodelled for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin by Hitler’s favorite architects Werner March (whose father, Otto March, designed the original 1913 stadium) and Albert Speer, the Olympiastadion was a symbol of power for the National Socialist party and an opportunity to present propaganda in the form of architecture. Being the westernmost structure on Hitler’s ‘capital city of the world’, the stadium was designed to present the then National Socialist Germany to the rest of the world as a power to be reckoned with. Any visitor to the stadium doesn’t only see the gigantic stadium, but also experiences the whole Olympic complex. Visitors would arrive at a 10-platform S-Bahn station able to serve at high frequencies for large events and then walk several hundred meters with a clear view of the huge imposing stone stadium as soon as visitors reached the car park. Though some might argue that neither the U- nor S-Bahn stations named after the stadium provided convenient access to the sports grounds, one has to consider the scale of the event. -

CTV Re Coverage of the Fatal Luge Accident at the 2010 Winter Olympic Games

CANADIAN BROADCAST STANDARDS COUNCIL NATIONAL CONVENTIONAL TELEVISION PANEL CTV re coverage of the fatal luge accident at the 2010 Winter Olympic Games (CBSC Decision 09/10-0895+) Decided November 12, 2010 R. Cohen (Chair), H. Pawley (Vice-Chair, Public), D. Braun (ad hoc), M. Harris (ad hoc), F. Niemi, T. Reeb THE FACTS On February 12, 2010, just prior to the commencement of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, a Georgian luge athlete named Nodar Kumaritashvili experienced a tragic accident during a practice run at the Whistler Sliding Centre. He flew off his luge coming out of a steep turn (corner 16, called “Thunderbird”), was projected off the track, and struck one of the support posts. The accident was caught on film by CTV (a member of the Olympic Broadcast Media Consortium and the principal English- language broadcaster of the Games), and was broadcast at various times that day, both as news of the accident was breaking and again later once it had been confirmed that Kumaritashvili had died from his injuries. The video was approximately 40 seconds in duration. It showed Kumaritashvili going down the luge track at a very fast speed (said to be 143 km/h). Multiple cameras were placed along the track so that the television audience could see his and all other runs from different points along the track and at different angles. When the luger flew off the sled, viewers heard a clang, which was presumably the sound of the luger’s helmet hitting the post. Kumaritashvili’s limp body was partially obscured by other posts in front of the camera, but the CTV audience saw a number of people, mainly on-site medics, running towards the man. -

Introduction to Sustainability Sustainability Essentials

SUSTAINABILITY ESSENTIALS A SERIES OF PRACTICAL GUIDES FOR THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT INTRODUCTION TO SUSTAINABILITY SUSTAINABILITY ESSENTIALS SUSTAINABILITY ESSENTIALS Sustainability is one of the most pressing • The IOC as an organisation: To embrace challenges of our time across a wide sustainability principles and to include spectrum of social, environmental and sustainability in its day-to-day operations. economic matters. Major issues such as climate change, economic inequality and • The IOC as owner of the Olympic social injustice are affecting people Games: To take a proactive and leadership throughout the world. These are also role on sustainability and ensure that it is pressing concerns for the sports community, included in all aspects of the planning and both for managing its day-to-day affairs and staging of the Olympic Games. for its responsibilities towards young people and future generations. We also recognise • The IOC as leader of the Olympic that sport has an unrivalled capacity to Movement: To engage and assist Olympic motivate and inspire large numbers of Movement stakeholders in integrating people. This is why we believe that the sustainability within their own organisations Olympic Movement has both a duty and an and operations. opportunity to contribute actively to global sustainability in line with our vision: “Building Following on from Olympic Agenda 2020, a better world through sport”. we issued the IOC Sustainability Strategy in December 2016. The Strategy is based on It is therefore logical that sustainability forms our three spheres of responsibility and five one of the key elements of Olympic Agenda focus areas, as illustrated below. 2020, the Olympic Movement’s strategic roadmap adopted in December 2014. -

Gendered Coverage and Newsroom Practices in Online Media: a Study of Reporting of the 2008 Olympic Games by the ABC, BBC and CBC

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2015 Gendered coverage and newsroom practices in online media: a study of reporting of the 2008 Olympic Games by the ABC, BBC AND CBC Dianne M. Jones University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Jones, Dianne M., Gendered coverage and newsroom practices in online media: a study of reporting of the 2008 Olympic Games by the ABC, BBC AND CBC, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2015.