2011 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece

CLASSICAL PRESENCES General Editors Lorna Hardwick James I. Porter CLASSICAL PRESENCES The texts, ideas, images, and material culture of ancient Greece and Rome have always been crucial to attempts to appropriate the past in order to authenticate the present. They underlie the mapping of change and the assertion and challenging of values and identities, old and new. Classical Presences brings the latest scholarship to bear on the contexts, theory, and practice of such use, and abuse, of the classical past. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece YANNIS HAMILAKIS 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Yannis Hamilakis 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Hamilakis Nation and Its Ruins.Pdf

CLASSICAL PRESENCES General Editors Lorna Hardwick James I. Porter CLASSICAL PRESENCES The texts, ideas, images, and material culture of ancient Greece and Rome have always been crucial to attempts to appropriate the past in order to authenticate the present. They underlie the mapping of change and the assertion and challenging of values and identities, old and new. Classical Presences brings the latest scholarship to bear on the contexts, theory, and practice of such use, and abuse, of the classical past. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece YANNIS HAMILAKIS 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Yannis Hamilakis 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Public Relations and Communication Department [email protected] Tel.: 210 6505600 Fax : 210 6505934

Public Relations and Communication Department [email protected] Tel.: 210 6505600 fax : 210 6505934 Athens, September 21, 2017 PRESS RELEASE - Announcements Postal of Cadastral Survey in the municipalities of Edessa and Almopia of the region of Central Macedonia. "Check, confirm, correct" NCMA SA has made the following announcement: On Thursday September 21, 2017, the Posting of Cadastral Data starts in the local Municipalities/Communities of: Aloros, Aridaia, Archangelos, Apsalos, Voreinos, Garefeio, Dorothea, Exaplatanos, Theodoraki, Thiriopetra, Ida, Konstantia, Loutraki, Lykostomo, Megaplatanos, Milea, Neromyloi, Notia, Xifiani, Ormi, Perikleia, Piperies, Polikarpio, Promachoi, Sarakinoi, Sosandra, Tsakoi, Filoteia, Foustani, Chrysi of the Kallikratis Municipality of Almopia and the local Municipalities/Communities of Agios Athanasios, Agra, Arnissi, Vryta, Grammatiko, Karydia, Mesimeri, Nisi, Panagitsa, Peraia, Platani, Rizari, Sotira, Flamouria of the Kallikratis Municipality of Edessa of P.E. of Pella of the region of Central Macedonia. Anyone with a legitimate interest may make an application to correct or appeal against posted data at the competent Cadastral Survey Office within two (2) months of the above date. For expatriates and the Greek State the deadline is four (4) months. In particular, for the application for correction of a manifest error, the submission deadline is until July 31, 2018. Until the same date, overdue declarations may also be submitted. To better serve rightholders, excerpts from the Cadastral Tables and Charts have been sent to them by post to the contact address declared by each citizen. Through Posting, owners of real property are able to check that their ownership is registered and correct any errors. This process ensures that the cadastral survey will be completed properly and there will be no problems in the subsequent operation of the Cadastre. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

NIMBY Syndrome and Landfills

ORIGINAL ARTICLE N.I.M.B.Y. Syndrome and Landfills: The case of the landfills in the Region of Pella and the emergence of a NIMBY syndrome Y. Frangopoulos, E. Kolovou, D. Kourkouridis Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Abstract: The main aim of the paper is the exploration of a possible Not in My Backyard Phenomenon (NIMBY) in the region of Pella, because of the irrational functioning of the Landfills of Aridaia and Edessa. The exploration that central hypothesis initially attempted through clarification of bibliographic and theoretical sources (social, economic, political, etc.) involved in the expression of the syndrome N.I.M.Β.Y. and with regard to the waste management practices. The primary research with questionnaires and interviews concerned the inhabitants of the communities that are located in the area of the landfills of Aridaia and Edessa. The objective was to relate the environmental knowledge and citizens’ action with their socio-demographic and educational profile and ultimately their willingness to play a role in participatory planning and environmental control processes of the landfills operating in their areas. Our parallel objective was to identify the potential factors that may be a cause of rebound NIMBY phenomena. Keywords: N.I.M.B.Y. (Not In My Back Yard); Landfills; waste management; sociology of space; Regional Unit of Pellas 1. Introduction The so–called N.I.M.B.Y. syndrome refers to models that are based simply on the social reaction of citizens against unwanted facilities that can generate environmental, economical, social (exclusion) and other dangers. The territorial adjacency of place with an activity which from social regard is comprehended as dangerous and threatening, leads to various behaviours of opposition. -

![English: - "Woof, Woof Dear Lord and Other Stories", [Tr.By]: Leo Marshall, Athens: Kedros, 1995](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0202/english-woof-woof-dear-lord-and-other-stories-tr-by-leo-marshall-athens-kedros-1995-2210202.webp)

English: - "Woof, Woof Dear Lord and Other Stories", [Tr.By]: Leo Marshall, Athens: Kedros, 1995

0161100008 POLYPHONIC CARAVAN- LETTERS OF CONSENT- LIST I ITH NAMEQE THE I ENTITY LGROUP CAPACITY GENDE 1c~l-JM' I CIH SIGNATORY/RIES REfRESENIED OF THE ROF - IBYTHE SIGNAIQRYL THE LE g[oliPAV) . 201 9 SIGNAIQRY/ lES. SIGNAI N EMBE RIES QRYL IES N · ~-~. ...... ??~ 5 - 1. Nikolaos Arvanitis Non-profit Member of the Male organization Board of Tel: +30 2103310919 "Apiros" (Intemati Directors Website: anal Polyphonic www.polyphonic.gr Song Festival - Facebook site: Polyphonic Polyphonic Caravan, Facebook Caravan) group: POLYPHONIC SONG ' You tube: Polyphonicfestival, A pi 13os - 2. Aliki Gkana, Ourania Polyphonic Group Interpreters of Male (4), Mixed Batsinila, Katerina "Chaonia" the polyphonic Female group Euthimiou, Penny song, Members (8) Spyropoulou, Evi of the Makatsori, Eleni Gerakiti, Polyphonic Christos Diplas, Giorgos Group Diochnos, Giorgos Toutsis, "Chaonia" Daphne Tsiavou, Eugenia Kagianni, I. Alexandros Lambridis Tel: + 30 6973342113 Email: [email protected] Facebook site: CHAONIA polyphonic group 3. Vaggelis Kotsou Polyphonic Group Interpreter of Male Mixed "Polyphonico of the polyphonic groups Tel: + 30 6944446186 Epirus" (V. song, Teacher Email: Kotsou), of Polyphonic yagg!::lis.kQtsmi@gwai].cQm Polyphonic Group and Folk Song, "Pentatono", Musician, Polyphonic Group Member and of the Association Representative "Xenia" of ofthe Kalamata Polyphonic Groups "Polyphonico ofEpirus" (V. ' Kotsou), "Pentatono'', Polyphonic Group ofthe Association "Xenia" of Kalamata -- - - POLYPHONIC CARAVAN – LETTERS OF CONSENT - LIST 4. Kostas Katsavaras -

EVIDENCE of ORPHIC MYSTERY CULT in ARCHAIC MACEDONIAN and THRACIAN BURIALS by Lisa Tweten a THESIS SUBMITTED in PARTIAL FULFILLM

EVIDENCE OF ORPHIC MYSTERY CULT IN ARCHAIC MACEDONIAN AND THRACIAN BURIALS by Lisa Tweten A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Ancient Cultures, Religion and Ethnicity) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2015 © Lisa Tweten, 2015 Abstract Gold foil is found in numerous burials in the Mediterranean dating to the early Mycenaean period and the material was used as clothing attachments, jewelry, headbands, wreaths, and other decorative adornments. One of the more distinctive uses of gold foil was as a mouth-plate (or epistomion), which is an ellipsoidal or rhomboidal piece of gold foil placed on the mouth of the deceased in a burial. An apparent increase in artifact occurrence in Macedonia during the archaic period was the impetus for this thesis, as a change in grave goods suggests a change in funerary rituals. This change may be linked to the rise of local private cults, including mystery cults, that took place in the archaic period. Furthermore, these artifacts are stylistically, materially, and contextually similar to the later Classical and Hellenistic periods use of gold foil for the inscribed Orphic gold tablets. The inscribed Orphic tablets have clear links to mystery cults and are related to both the initiation and the afterlife expectations of the deceased. Taking a selection of the uninscribed gold foil mouth-plates found in archaic burials of Macedonia and Thrace, this thesis examines the potential links between these two practices and asks whether the uninscribed gold foil mouth-plates can be assigned to the category of 'things Orphic', or if they are part of an unrelated burial tradition. -

Chronique Archéologique De La Religion Grecque (Chronarg)

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 26 | 2013 Varia Chronique archéologique de la religion grecque (ChronARG) Joannis Mylonopoulos, Michael Fowler, Emmanuel Voutiras, Kalliopi Chatzinikolaou, Alexis D’Hautcourt, Natacha Massar, Stéphanie Paul, Christina Mitsopoulou, Thomas Brisart, Massimo Osanna, Ilaria Battiloro et Nicola Cucuzza Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2217 DOI : 10.4000/kernos.2217 ISSN : 2034-7871 Éditeur Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Édition imprimée Date de publication : 10 octobre 2013 Pagination : 303-380 ISSN : 0776-3824 Référence électronique Joannis Mylonopoulos, Michael Fowler, Emmanuel Voutiras, Kalliopi Chatzinikolaou, Alexis D’Hautcourt, Natacha Massar, Stéphanie Paul, Christina Mitsopoulou, Thomas Brisart, Massimo Osanna, Ilaria Battiloro et Nicola Cucuzza, « Chronique archéologique de la religion grecque (ChronARG) », Kernos [En ligne], 26 | 2013, mis en ligne le 25 novembre 2015, consulté le 02 mars 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2217 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2217 Kernos Kernos 26 (2013), p. 303-380. Chronique archéologique de la religion grecque (ChronARG) [01. Athènes, Attique, Mégaride] [02. Péloponnèse] 03. Béotie, Eubée (Ioannis MYLONOPOULOS et Michael FOWLER) Béotie 03.01 – Agia Triada – Grotte de la Nymphe de Coronée – Éphorie de Paléoanthropologie et de Spéléologie de la Grèce méridionale – Des matériaux provenant des fouilles clandestines du côté S et des niches du côté N de la grotte ont été ramassés lors d’un nettoyage de surface. Les objets recueillis comptent des figurines des périodes classique et hellénistique représentant Pan, des femmes assises, des protomés et des animaux, ainsi que des tessons et des vases intacts (petits cotyles et un lécythe non peint), ca 400 astragales, un morceau de stéatite, des perles, une partie d’un bijou perforé, des fragments de marbre (non spécifiés), des aiguilles et des épingles en os. -

Information and Communication Technologies As Agricultural Extension Tools

Scientific Bulletin – Economic Sciences, Vol. 10/ Issue 1 INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES AS AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION TOOLS Anatoli Marantidou 1, Anastasios Michailidis 2 and Afroditi Papadaki-Klavdianou 3 1Department of Agricultural Economics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece [email protected] 2Department of Agricultural Economics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece [email protected] 3Department of Agricultural Economics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece [email protected] Abstract: Knowledge and innovation society are becoming priorities to the welfare and quality of life of the rural population. This is based substantially on scientific and technological progress. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) accelerate rural development by contributing to more efficient management and rapid knowledge dissemination. ICTs are defined as a different set of technological tools and resources used for communication and for the creation, processing, dissemination, storage and information management. The rapid revolution in modern agriculture has led to investigations in many regions. One of them is the rural region of the prefecture of Pella that exists many years in the agricultural sector. The objective of this research is to evaluate the adoption of ICTs among farmers and determine the importance of agricultural extension as an information source in the region of Central Macedonia. For this purpose, the approaches of summary statistics in combination with multivariate statistical analysis techniques have been used. In particular, through the statistical package SPSS (v.16.0), there were employed two correlation methods: (a) the categorical regression model and (b) the two-step clustering. The primary research data were collected using a specifically constructed questionnaire, supplemented by personal interviews with farmers of the prefecture of Pella. -

Report Date: 06.06.2008 ISBN Grading: Open 978-82-7385-135-4 Quarryscapes Deliverable Number: 7 Number of Pages: 40 + 489 (Appendix) Map Enclosures

Site Management Concepts for Widan el Faras, Northern Fayoum, Egypt Prepared by NSCE With the close collaboration with Naguib Amin North South Consultant Exchange (NSCE) Work package 6: Egypt conservation concept: Management plan for Widan el-Faras Innovation acivity Report date: 06.06.2008 ISBN Grading: Open 978-82-7385-135-4 QuarryScapes deliverable number: 7 Number of pages: 40 + 489 (appendix) Map enclosures: Keywords: Faiyum Ancient quarries Basalt Protected area Egypt UNESCO site Ancient road Conservation QuarryScapes: Conservation of Ancient Stone Quarry Landscapes in the Eastern Mediterranean QuarryScapes is the first project of its kind for addressing the importance of ancient quarry landscapes and raising the awareness of the urgent needs for protecting such sites. QuarryScapes will develop scientific and practical methodologies for documentation, characterisation and conservation of ancient quarry landscapes, raise the awareness of their significance and vulnerability and contribute to legal protection measures and sustainable management. Through case studies in Egypt, Jordan and Turkey, the project will address development of theoretical and practical methods pertaining to the major steps in the process of conservation: from recognition, investigation and assessment of significance, to understanding the risks, developing sound conservation and monitoring concepts, and suggesting mechanisms for sustainable management. The project is subdivided in ten work packages. Coordinator: The Geological Survey of Norway (NGU) Partners: -

Between, Against, Beyond: Challenging National Identities in Contemporary Greek Theatre Dissertation Zur Erlangung Des Grades E

Between, Against, Beyond: Challenging National Identities in Contemporary Greek Theatre Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Ariadni Lignou Tsamantani Berlin 2020 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Matthias Warstat Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Miltos Pechlivanos Tag der Disputation: 9. Juli 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................... 3 Preface ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 6 1. Framing this study: concepts, contexts, histories ............................................................. 20 1.1 On nation, nationalism and identity ............................................................................ 20 1.2 On nation and theatre .................................................................................................. 28 1.3 Greek (theatre) histories: pasts and presents .............................................................. 36 1.3.1 Nation-state and theatre stage ............................................................................. 37 1.3.2 Performing nation on/as “national stage” .......................................................... -

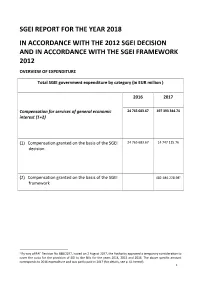

Sgei Report for the Year 2018 in Accordance with the 2012 Sgei Decision and in Accordance with the Sgei Framework 2012 Overview of Expenditure

SGEI REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2018 IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE 2012 SGEI DECISION AND IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE SGEI FRAMEWORK 2012 OVERVIEW OF EXPENDITURE Total SGEI government expenditure by category (in EUR million ) 2016 2017 Compensation for services of general economic 24 765 683.67 497 393 344.74 interest (1+2) (1) Compensation granted on the basis of the SGEI 24 765 683.67 14 747 115.76 decision (2) Compensation granted on the basis of the SGEI 482 646 228.981 framework 1 By way of RAE Decision No 688/2017, issued on 2 August 2017, the Authority approved a temporary consideration to cover the costs for the provision of SGI to the NIIs for the years 2014, 2015 and 2016. The above specific amount corresponds to 2016 expenditure and was partly paid in 2017 (for details, see p. 61 hereof). 1 I. APPLICATION OF THE 2012 SGEI DECISION 1. SOCIAL SGEI Clear and comprehensive description of how the respective services are organized in your Member State. Explanation of what kind of services in the respective sector have been defined as SGEI in your Member State. Please list the contents of the services entrusted as SGEIs as clearly as possible. Services designated as social SGEIs fall into two categories: (A) Provision and operation of structures to tackle poverty in various municipalities in the country. These structures include the following: - Social Pharmacy; - Social Grocery Stores; - Social Meals Scheme; - Mediation Office; - Time Exchange; - Homeless Day Reception Centre; - Homeless Hostel. Through the operation of the above structures, psychosocial support and information services are also provided for the empowerment and social integration of the beneficiaries.