Confronting the Unknown: Tejanas in the Transformation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“I Go for Independence”: Stephen Austin and Two Wars for Texan Independence

“I go for Independence”: Stephen Austin and Two Wars for Texan Independence A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by James Robert Griffin August 2021 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by James Robert Griffin B.S., Kent State University, 2019 M.A., Kent State University, 2021 Approved by Kim M. Gruenwald , Advisor Kevin Adams , Chair, Department of History Mandy Munro-Stasiuk , Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………...……iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………v INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………..1 CHAPTERS I. Building a Colony: Austin leads the Texans Through the Difficulty of Settling Texas….9 Early Colony……………………………………………………………………………..11 The Fredonian Rebellion…………………………………………………………………19 The Law of April 6, 1830………………………………………………………………..25 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….32 II. Time of Struggle: Austin Negotiates with the Conventions of 1832 and 1833………….35 Civil War of 1832………………………………………………………………………..37 The Convention of 1833…………………………………………………………………47 Austin’s Arrest…………………………………………………………………………...52 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….59 III. Two Wars: Austin Guides the Texans from Rebellion to Independence………………..61 Imprisonment During a Rebellion……………………………………………………….63 War is our Only Resource……………………………………………………………….70 The Second War…………………………………………………………………………78 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….85 -

Antonio Lopez De Santa Anna ➢ in 1833 Santa Anna Was Elected President of Mexico, After Overthrowing Anastacio Bustamante

Road To Revolution PoliticAL uNREST IN TEXAS ➢ Haden Edwards received his Empresario contract from the Mexican Government in 1825. ➢ This contract allowed him to settle 800 families near Nacogdoches. ➢ Upon arrival, Edwards found that there had been families living there already. These “Old Settlers” were made up of Mexicans, Anglos, and Cherokees. ➢ Edwards’s contract required him to respect the property rights of the “old settlers” but he thought some of those titles were fake and demanded that people pay him additional fees for land they had already purchased. Fredonian Rebellion ➢ After Edward’s son-in-law was elected alcalde of the settlement, “old settlers” suspected fraud. ➢ Enraged, the “old settlers” got the Mexican Government to overturn the election and ultimately cancel Edwards’s contract on October 1826. ➢ Benjamin Edwards along with other supporters took action and declared themselves free from Mexican rule. Fredonian Rebellion (cont.) ➢ The Fredonian Decleration of Independance was issued on December 21, 1826 ➢ On January 1827, the Mexican government puts down the Fredonian Rebellion, collapsing the republic of Fredonia. MIer y Teran Report ➢ At this point, Mexican officials fear they are losing control of Texas. ➢ General Manuel de Mier y Teran was sent to examine the resources and indians of Texas & to help determine the formal boundary with Louisiana. Most importantly to determine how many americans lived in Texas and what their attitudes toward Mexico were. ➢ Mier y Teran came up with recommendations to weaken TX ties with the U.S. so Mexico can keep TX based on his report. His Report: His Recommendations: ➢ Mexican influence ➢ To increase trade between decreased as one moved TX & Mexico instead with northward & eastward. -

SANCHEZ MORENO.Pdf

LOS INDIOS “BÁRBAROS” EN LA FRONTERA NORESTE DE NUEVA ESPAÑA ENTRE 1810 Y 1821. Francisco Javier Sánchez Moreno, Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, CSIC RESUMEN: En este artículo estudiamos la participación de comanches y mescaleros en la emboscada de Baján como resultado de la política que las autoridades de las Provincias Internas habían mantenido con los indios “bárbaros” en los años inmediatamente anteriores a la Insurgencia. Asimismo, analizamos los cambios que posteriormente se manifestaron en las relaciones entre las bandas nómadas y las autoridades virreinales. PALABRAS CLAVE: “bárbaros”, Provincias Internas, Insurgencia. ABSTRACT: This article studies the Comanche and Mescaleros’ participation in the ambush of Baján as a consequence of the policy that Interior Provinces’ authorities maintained with the “barbarians” Indians years before the Insurgence. We analyze also the later changes in the relations between nomadic bands and viceroyalty authorities. KEYWORDS: “barbarians”, Interior Provinces, Insurgence. Los nómadas en el norte de Nueva España Las relaciones con los “bárbaros” desde finales del siglo XVIII El 21 de marzo de 1811 un grupo heterogéneo de indios “auxiliares” colaboró con los realistas en la aprehensión de Miguel Hidalgo, Ignacio Allende, Mariano Recibido 9 02 2011 Evaluado 30 05 2011 Jiménez y cerca de novecientos insurgentes.1 Concretamente, según el parte que rindió don Simón de Herrera al comandante general Nemesio Salcedo sobre el momento de la captura, se hallaron presentes en esta acción indios comanches, mescaleros y otros reducidos en la misión del Dulce Nombre de Jesús de Peyotes.2 Aunque hay autores que limitan el número de todos a treinta y dos, en este parte solamente se señala que treinta y nueve fueron situados a vanguardia en el momento en el que se iniciaron las operaciones. -

"Patria É Intereses": Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado

3DWULD«LQWHUHVHV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH2ULJLQVDQG &KDQJLQJ0HDQLQJVRI,OXVWUDGR Caroline Sy Hau Philippine Studies, Volume 59, Number 1, March 2011, pp. 3-54 (Article) Published by Ateneo de Manila University DOI: 10.1353/phs.2011.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/phs/summary/v059/59.1.hau.html Access provided by University of Warwick (5 Oct 2014 14:43 GMT) CAROLINE SY Hau “Patria é intereses” 1 Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado Miguel Syjuco’s acclaimed novel Ilustrado (2010) was written not just for an international readership, but also for a Filipino audience. Through an analysis of the historical origins and changing meanings of “ilustrado” in Philippine literary and nationalist discourse, this article looks at the politics of reading and writing that have shaped international and domestic reception of the novel. While the novel seeks to resignify the hitherto class- bound concept of “ilustrado” to include Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), historical and contemporary usages of the term present conceptual and practical difficulties and challenges that require a new intellectual paradigm for understanding Philippine society. Keywords: rizal • novel • ofw • ilustrado • nationalism PHILIPPINE STUDIES 59, NO. 1 (2011) 3–54 © Ateneo de Manila University iguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado (2010) is arguably the first contemporary novel by a Filipino to have a global presence and impact (fig. 1). Published in America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and in Great Britain by Picador, the novel has garnered rave reviews across Mthe Atlantic and received press coverage in the Commonwealth nations of Australia and Canada (where Syjuco is currently based). -

Anales De Literatura Española Núm. 23, 2011

ÚLTIMOS NÚMEROS PUBLICADOS DE ANALES DE LITERATURA ESPAÑOLA Narradoras hispanoamericanas desde la Independencia a nuestros días Anales de Literatura Española Nº 16 (2003). Serie Monográfica, nº 6 Edición de Carmen Alemany Bay Nº 23, 2011 (SERIE MONOGRÁFICA, núm. 13) Universidad de Alicante Literatura española desde 1975 Nº 17 (2004). Serie Monográfica, nº 7 Edición de José María Ferri y Ángel L. Prieto de Paula Romanticismo español e hispanoamericano. «Cantad, hermosas» Homenaje al profesor Ermanno Caldera Nº 18 (2005). Serie Monográfica, nº 8 Escritoras ilustradas y románticas Edición de Enrique Rubio Cremades Edición de Helena Establier Pérez Humor y humoristas en la España del Franquismo Nº 19 (2007). Serie Monográfica, nº 9 María angulo EgEa Hombre o mujer, cuestión de apariencia. Un caso de travestismo en el teatro del siglo xviii · María Edición de Juan A. Ríos Carratalá JEsús garcía garrosa La otra voz de María Rosa de Gálvez: las traducciones de una dramaturga neoclásica · Frédé- riquE Morand Influencias medievales y originalidad en la literatura gaditana de finales del setecientos: el caso de la Escritores olvidados, raros y marginados Nª 20 (2008). Serie Monográfica, nº 10 gaditana María Gertrudis de Hore · HElEna EstabliEr PérEz Las esclavas amazonas (1805) de María Rosa de Gálvez en Edición de Enrique Rubio Cremades la comedia popular de entresiglos · EMilio Palacios FErnándEz Bibliografía general de escritoras españolas del siglo Nº 23, 2011 xviii lizabEtH ranklin Ewis · E F l La caridad de una mujer: modernización y ambivalencia sentimental en la escritura · ariEta antos asEnavE La memoria literaria del franquismo femenina decimonónica · M c c Escritura y mujer 1808-1838: los casos de Frasquita Larrea, Mª Nº 21 (2009). -

Stephen F. Austin and the Empresarios

169 11/18/02 9:24 AM Page 174 Stephen F. Austin Why It Matters Now 2 Stephen F. Austin’s colony laid the foundation for thousands of people and the Empresarios to later move to Texas. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Moses Austin, petition, 1. Identify the contributions of Moses Anglo American colonization of Stephen F. Austin, Austin to the colonization of Texas. Texas began when Stephen F. Austin land title, San Felipe de 2. Identify the contributions of Stephen F. was given permission to establish Austin, Green DeWitt Austin to the colonization of Texas. a colony of 300 American families 3. Explain the major change that took on Texas soil. Soon other colonists place in Texas during 1821. followed Austin’s lead, and Texas’s population expanded rapidly. WHAT Would You Do? Stephen F. Austin gave up his home and his career to fulfill Write your response his father’s dream of establishing a colony in Texas. to Interact with History Imagine that a loved one has asked you to leave in your Texas Notebook. your current life behind to go to a foreign country to carry out his or her wishes. Would you drop everything and leave, Stephen F. Austin’s hatchet or would you try to talk the person into staying here? Moses Austin Begins Colonization in Texas Moses Austin was born in Connecticut in 1761. During his business dealings, he developed a keen interest in lead mining. After learning of George Morgan’s colony in what is now Missouri, Austin moved there to operate a lead mine. -

The Mexican-American Press and the Spanish Civil War”

Abraham Lincoln Brigades Archives (ALBA) Submission for George Watt Prize, Graduate Essay Contest, 2020. Name: Carlos Nava, Southern Methodist University, Graduate Studies. Chapter title: Chapter 3. “The Mexican-American Press and The Spanish Civil War” Word Count: 8,052 Thesis title: “Internationalism In The Barrios: Hispanic-Americans and The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939.” Thesis abstract: The ripples of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) had a far-reaching effect that touched Spanish speaking people outside of Spain. In the United States, Hispanic communities –which encompassed Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Mexicans, Spaniards, and others— were directly involved in anti-isolationist activities during the Spanish Civil War. Hispanics mobilized efforts to aid the Spanish Loyalists, they held demonstrations against the German and Italian intervention, they lobbied the United States government to lift the arms embargo on Spain, and some traveled to Spain to fight in the International Brigades. This thesis examines how the Spanish Civil War affected the diverse Hispanic communities of Tampa, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Against the backdrop of the war, this paper deals with issues regarding ethnicity, class, gender, and identity. It discusses racism towards Hispanics during the early days of labor activism. It examines ways in which labor unions used the conflict in Spain to rally support from their members to raise funds for relief aid. It looks at how Hispanics fought against American isolationism in the face of the growing threat of fascism abroad. CHAPTER 3. THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN PRESS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR During the Spanish Civil War, the Mexican-American press in the Southwest stood apart from their Spanish language counterparts on the East Coast. -

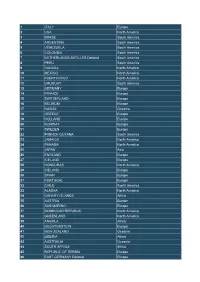

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Redalyc.La Reacción Realista Ante Las Conspiraciones Insurgentes En La

Secuencia. Revista de historia y ciencias sociales ISSN: 0186-0348 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora México de Andrés Martín, Juan Ramón La reacción realista ante las conspiraciones insurgentes en la frontera de Texas (1809-1813) Secuencia. Revista de historia y ciencias sociales, núm. 71, mayo-agosto, 2008, pp. 33-62 Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=319127427003 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín Doctor en Historia Contemporánea por la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid. SNI nivel r, profesor de Historia Contemporánea de América Latina en la Unidad Académica Multidisciplinaria de Ciencias, Educación y Humanidades (UAMCEH), Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas (UAT-México). Ha publicado: El cisma mellista: historia deuna ambición política, Editorial Actas, Madrid, 2000, 269 pp . (colección Luis Hernando de Larramendi);]osé María Otero de Navascllés, marqués deHermosilla: la baza nzalear y científica delmundo hispánico durante la guerra fría, Plaza y Valdés/Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, México 2005, 167 pp.; La hegemonía bene volente. Un estudio sobre la política exterior de Estadas Unidos y la prensa tamaulipeca, Miguel Angel Porrúa/Corxcvr (Consejo Tamaulipcco de Ciencia y Tecnología) , México, 2005, 180 pp.; colabo rador del li bro colectivo, Procesos y comportamientos en la configuración de México, Plaza y Valdés/Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, México, 2008 (en prensa). -

Tejano Soldados for the Union and Confederacy

National Park Service Shiloh U.S. Department of the Interior Use a “short-hand” version of the site name here (e.g. Palo Alto Shiloh National Military Paper Battlefield not Palo Alto Battlefield National Historical Site) set in Mississippi-Tennessee 29/29 B Frutiger bold. Tejano Soldados For The Union And Confederacy "...know that reason has very little influence in this world: prejudice governs." -Wm. T. Sherman 1860 Duty and Sacrifice Mired Warfare was nothing new to the Mexican- Those hispanics which did serve, seemed not in Prejudice Americans (Tejanos) of the western American to identify with, nor understand, the origins frontier. Since the moment the first hispanic of this truly American war, and most soldados soldiers (soldados) and missionaries pushed approached the issues with considerable northward from Mexico, into the vast expanse apathy, whether in blue or gray. The wartime of the American southwest, a daily struggle performance of the Tejano recruit is hard to for survival had existed. Conflicts with Indian assess. He did have a tendency to desert the inhabitants, a series of internal revolutions, service. The desertion rate in some Texas and the Texas War for Independence, and the New Mexico Volunteer militia units, made up Mexican War with the United States had of hispanics, often ran as high as 95 to 100 tempered the hispanic peoples of North percent. These men deserted their units most America to the realities and rigors of war. often, not because of any fear of death or service, but because of a constant prejudice Despite this, hispanics did not respond to the that existed within the mostly white Union American Civil War with the strong emo- and Confederate forces. -

Mexican American History Resources at the Briscoe Center for American History: a Bibliography

Mexican American History Resources at the Briscoe Center for American History: A Bibliography The Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin offers a wide variety of material for the study of Mexican American life, history, and culture in Texas. As with all ethnic groups, the study of Mexican Americans in Texas can be approached from many perspectives through the use of books, photographs, music, dissertations and theses, newspapers, the personal papers of individuals, and business and governmental records. This bibliography will familiarize researchers with many of the resources relating to Mexican Americans in Texas available at the Center for American History. For complete coverage in this area, the researcher should also consult the holdings of the Benson Latin American Collection, adjacent to the Center for American History. Compiled by John Wheat, 2001 Updated: 2010 2 Contents: General Works: p. 3 Spanish and Mexican Eras: p. 11 Republic and State of Texas (19th century): p. 32 Texas since 1900: p. 38 Biography / Autobiography: p. 47 Community and Regional History: p. 56 The Border: p. 71 Education: p. 83 Business, Professions, and Labor: p. 91 Politics, Suffrage, and Civil Rights: p. 112 Race Relations and Cultural Identity: p. 124 Immigration and Illegal Aliens: p. 133 Women’s History: p. 138 Folklore and Religion: p. 148 Juvenile Literature: p. 160 Music, Art, and Literature: p. 162 Language: p. 176 Spanish-language Newspapers: p. 180 Archives and Manuscripts: p. 182 Music and Sound Archives: p. 188 Photographic Archives: p. 190 Prints and Photographs Collection (PPC): p. 190 Indexes: p. -

Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines

Title: Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines Teacher: Anne Sharkey, Huntley High School Summary: This lesson took part as a comparison of the different aspects of the Spanish maritime empires with a comparison of Spanish colonization of Mexico & Cuba to that of the Philippines. The lessons in this unit begin with a basic understanding of each land based empire of the time period 1450-1750 (Russia, Ottomans, China) and then with a movement to the maritime transoceanic empires (Spain, Portugal, France, Britain). This lesson will come after the students already have been introduced to the Spanish colonial empire and the Spanish trade systems through the Atlantic and Pacific. Through this lesson the students will gain an understanding of Spanish systems of colonial rule and control of the peoples and the territories. The evaluation of causes of actions of the Spanish, reactions to native populations, and consequences of Spanish involvement will be discussed with the direct correlation between the social systems and structures created, the influence of the Christian missionaries, the rebellions and conflicts with native populations between the two locations in the Latin American Spanish colonies and the Philippines. Level: High School Content Area: AP World History, World History, Global Studies Duration: Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Compare the economic, political, social, and cultural structures of the Spanish involvement in Latin America with the Spanish involvement with the Philippines Compare the effects of mercantilism on Latin America and the Philippines Evaluate the role of the encomienda and hacienda system on both regions Evaluate the influence of the silver trade on the economies of both regions Analyze the creation of a colonial society through the development of social classes—Peninsulares, creoles, mestizos, mulattos, etc.