Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints and Angels, and Saints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Representations of Elderly People in the Scenes of Jesus’ Childhood in Tuscan Paintings, 14Th-16Th Centuries

The Representations of Elderly People in the Scenes of Jesus’ Childhood in Tuscan Paintings, 14th-16th Centuries The Representations of Elderly People in the Scenes of Jesus’ Childhood in Tuscan Paintings, 14th-16th Centuries: Images of Intergeneration Relationships By Welleda Muller The Representations of Elderly People in the Scenes of Jesus’ Childhood in Tuscan Paintings, 14th-16th Centuries: Images of Intergeneration Relationships By Welleda Muller This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Welleda Muller All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9049-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9049-6 This book is dedicated to all of my colleagues and friends from MaxNetAging: Inês Campos-Rodrigues, Kristen Cyffka, Xuefei Gao, Isabel García-García, Heike Gruber, Julia Hoffman, Nicole Hudl, Göran Köber, Jana Kynast, Nora Mehl, and Ambaye Ogato. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Acknowledgments .................................................................................... xiii Introduction ................................................................................................ -

"Nuper Rosarum Flores" and the Cathedral of Florence Author(S): Marvin Trachtenberg Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol

Architecture and Music Reunited: A New Reading of Dufay's "Nuper Rosarum Flores" and the Cathedral of Florence Author(s): Marvin Trachtenberg Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Autumn, 2001), pp. 740-775 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1261923 . Accessed: 03/11/2014 00:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Renaissance Society of America are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Renaissance Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.147.172.89 on Mon, 3 Nov 2014 00:42:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Architectureand Alusic Reunited: .V A lVewReadi 0 u S uperRosarum Floresand theCathedral ofFlorence. byMARVIN TRACHTENBERG Theproportions of the voices are harmoniesforthe ears; those of the measure- mentsare harmoniesforthe eyes. Such harmoniesusuallyplease very much, withoutanyone knowing why, excepting the student of the causality of things. -Palladio O 567) Thechiasmatic themes ofarchitecture asfrozen mu-sic and mu-sicas singingthe architecture ofthe worldrun as leitmotifithrough the histories ofphilosophy, music, and architecture.Rarely, however,can historical intersections ofthese practices be identified. -

"Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2017 "Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth Aaron Hubbell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hubbell, Aaron, ""Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4408. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THINGS NOT SEEN" IN THE FRESCOES OF GIOTTO: AN ANALYSIS OF ILLUSORY AND SPIRITUAL DEPTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and the School of Art in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History in The School of Art by Aaron T. Hubbell B.F.A., Nicholls State University, 2011 May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Elena Sifford, of the College of Art and Design for her continuous support and encouragement throughout my research and writing on this project. My gratitude also extends to Dr. Darius Spieth and Dr. Maribel Dietz as the additional readers of my thesis and for their valuable comments and input. -

Curriculum Simona Pasquinucci

CURRICULUM DOTT.SSA SIMONA PASQUINUCCI Simona Pasquinucci è nata a Empoli (Fi) il 6 aprile 1965. Titoli di studio: Maturità Classica presso il Liceo Ginnasio “Niccolò Forteguerri” di Pistoia nel 1983 con la votazione di 60/60; Laurea in Lettere presso l’Università degli Studi di Firenze relatore Prof. Mina Gregori nel 1991 con una tesi dal titolo “Giovanni Bonsi nella pittura Fiorentina della metà del Trecento” con la votazione di 110 /110 e lode; Diploma in Archivistica, Paleografia e Diplomatica presso l’Archivio di Stato di Firenze nel 1993 con la votazione di 63/70. Specializzazione in Beni Artistici conseguita presso la Scuola di Studi Umanistici e della Formazione di Firenze il 18 aprile 2019 con il massimo dei voti e menzione della lode. Esperienza professionale: Dal 27 luglio 1997 in servizio presso l’Amministrazione dei Beni Culturali (prima presso la Soprintendenza Beni Artistici e Storici per le Province di Firenze Pistoia e Prato, fino alla riforma del 2014 presso il Polo Museale Fiorentino; Polo Museale Regionale della Toscana fino al 30 giugno 2016); Dal primo luglio 2016 assegnata alle Gallerie degli Uffizi, con la qualifica di Assistente Amministrativo; Dal 14 luglio 2019 nomina a Storico dell’Arte. Capodivisione Curatoriale delle Gallerie degli Uffizi dal 2019 ad oggi. Attività scientifica: Fa parte del Consiglio direttivo dell’Associazione Corpus della Pittura Fiorentina. Ha iniziato nel 1991 la sua collaborazione con il Corpus della Pittura Fiorentina, sotto la guida del Prof. Miklos Boskovits, lavorando al volume, uscito nel 2000, “Tradition and Innovation in florentine Trecento Painting Giovanni Bonsi and Tommaso del Mazza” nel quale sono confluite le ricerche condotte per la tesi di laurea. -

Thoughts About Paintings Conservation This Page Intentionally Left Blank Personal Viewpoints

PERSONAL VIEWPOINTS Thoughts about Paintings Conservation This page intentionally left blank Personal Viewpoints Thoughts about Paintings Conservation A Seminar Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 EDITED BY Mark Leonard THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES & 2003 J- Paul Getty Trust THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Timothy P. Whalen, Director Los Angeles, CA 90049-1682 Jeanne Marie Teutónico, Associate Director, www.getty.edu Field Projects and Science Christopher Hudson, Publisher The Getty Conservation Institute works interna- Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief tionally to advance conservation and to enhance Tobi Levenberg Kaplan, Manuscript Editor and encourage the preservation and understanding Jeffrey Cohen, Designer of the visual arts in all of their dimensions— Elizabeth Chapín Kahn, Production Coordinator objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Austin, Texas scientific research; education and training; field Printed in Hong Kong by Imago projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. Library of Congress In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed Cataloging-in-Publication Data to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation Personal viewpoints : thoughts about paintings practice. conservation : a seminar organized by The J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 /volume editor, Mark Leonard, p. -

Daddi, Bernardo Also Known As Daddo, Bernardo Di Active by 1320, Died Probably 1348

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Daddi, Bernardo Also known as Daddo, Bernardo di active by 1320, died probably 1348 BIOGRAPHY Son of Daddo di Simone, Bernardo is recorded for the first time in the registers of the Arte dei Medici e Speziali when he enrolled in the guild (which also included artists) between 1312 and 1320.[1] By this date he must have been a firmly established painter, as the reconstruction of his oeuvre also suggests; presumably, he had been born by the last decade of the thirteenth century, if not earlier. His first securely dated work is the signed triptych in the Uffizi, Florence; its inscription contains not only the artist’s name but also the year 1328. Recent studies, however, have assigned various works, also of large dimensions, to previous years, such as the cycle of frescoes in the chapel of the Pulci and Berardi families in Santa Croce in Florence; the polyptych of San Martino at Lucarelli (Siena), now in the New Orleans Museum of Art; and the polyptych divided among the Galleria Nazionale in Parma, the Museo Lia in La Spezia, and a private collection.[2] Although perhaps trained in the circle of painters such as Lippo di Benivieni or the Master of San Martino alla Palma,[3] in the second or the early third decade of the fourteenth century Bernardo worked in close contact with Giotto’s shop (executing for the church of Santa Croce, then the preserve of the pupils and followers of the great master, not only the abovementioned frescoes but also possibly the Parma–La Spezia polyptych).[4] During the fourth and fifth decades of the century, Daddi’s shop seems to have produced by preference numerous small but precious panels destined for private devotion. -

Images-Within-Images in Italian Painting (1250-1350)

Images-within-Images in Italian Painting (1250-1350) Reality and Reflexivity Peter Bokody Plymouth University, UK ASHGATE Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 1 Essential Images-within-Images 11 2 Illusionism 37 3 Reality Effect 59 4 Nleta-Images 89 5 Meanings 113 6 Embedded Narrative 141 7 Image and Devotion 171 Conclusion 187 Bibliography 195 Index 221 List of Illustrations Color Plates 1 Model of the Stefaneschi polyptych. 8 Pietro Lorenzetti, St. John the Giotto di Bondone, Stefaneschi polyptych Evangelist Altar, before 1319, fresco. (back), between 1300-1330, tempera on Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi. wood. Pinacoteca, Vatican. 2014 © Photo © Stefan Diller. Scala, Florence. 9 Reliefs. Expulsion of the Devils from 2 Giotto di Bondone, Envy and Infidelity, Arez20, between 1288-1297, fresco. Upper between 1303-1305, fresco. Arena Chapel, Church, San Francesco, Assisi. © Stefan Padua. Courtesy of Comune di Padua - Diller. Department of Culture. 10 Frieze. Liberation of the Repentant of Francis. St. Francis and 3 Image St. Heretic, between 1288-1297, fresco. Upper stories his between 1260-1280, of life, Church, San Francesco, Assisi. © Stefan on wood. Chiesa di San tempera Diller. Silvestro Museo Diocesano d'Arte Sacra, Orte. 2014 © Photo DeAgostini Picture 11 Verification of the Stigmata, between Library/Scala, Florence. 1288-1297, fresco. Upper Church, San Francesco, Assisi. © Stefan Diller. 4 Painted cross. St. Francis before the Cross in San between Damiano, 12 Crucifixion. Giotto di Bondone, 1288-1297, fresco. Church, San Upper Allegory of Obedience, 1310s, fresco. Lower Francesco, Assisi. © Stefan Diller. Church, San Francesco, Assisi. © Stefan Diller. 5 Twisted column. -

WISHBOOK-2019.Pdf

FRONT COVER Crivelli Madonna with Child - Carlo Crivelli XV - XVI Century Art Department pages 136 - 139 Contents 3 4 Letter from the President of the Vatican City State 94 Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saints 6 Letter from the Director of the Vatican Museums 98 Enthroned Madonna and Child Letter from the International Director of the 102 Saints Paola and Eustochium 8 Patrons of the Arts 106 Stories of the Passion of Christ 110 Icons from the Tower of Pope John XXIII 10 BRAMANTE COURTYARD Long-term Project Report 126 XV – XVI CENTURY ART 16 CHRISTIAN ANTIQUITIES 128 Tryptich of the Madonna and Child with Saints 18 Drawn Replicas of Christian Catacombs Paintings 132 Apse of the Church of San Pellegrino 22 GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITIES 136 Crivelli Madonna with Child 24 Chiaramonti Gallery Wall XlV 140 Madonna and Child with Annunciation and Saints 30 Ostia Collection: Eleven Figurative Artifacts 144 XVII – XVIII CENTURY ART AND TAPESTRIES Ostia Collection: Two Hundred and Eighty-three 34 Household Artifacts 146 Noli Me Tangere Tapestry 38 Statue of an Old Fisherman 150 Plaster Cast of the Bust of Pope Pius VII 42 Polychrome Mosaic with Geometric Pattern 154 Two Works from the Workshop of Canova 162 Portrait of Pope Clement IX 46 GREGORIAN ETRUSCAN ANTIQUITIES 166 Embroidery Drawings for Papal Vestments 48 Krater, Kylixes and Perfume Jars 52 Gold Necklaces from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb 170 XIX CENTURY AND CONTEMPORARY ART 56 Astarita Collection: Thirty-three Figurative Vases 172 Clair de Lune 60 Ceremonial Clasp from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb 176 Model of Piazza Pius XII 64 Amphora and a Hundred Fragments of Bucchero 180 HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS 68 DECORATIVE ARTS 182 Two Jousting Shields 70 Rare Liturgical Objects 186 Drawing of the Pontifical Army Tabella 76 Tunic of “St. -

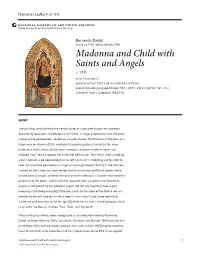

Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Bernardo Daddi active by 1320, died probably 1348 Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels c. 1345 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.2 x 24.2 cm (19 3/4 x 9 1/2 in.) overall (including engaged frame): 57.1 × 30.5 × 2.6 cm (22 1/2 × 12 × 1 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1952.5.61 ENTRY The painting, which formed the central panel of a portable triptych for domestic devotion,[1] represents the Madonna and Child, in larger proportions than the other figures in the composition, seated on a raised throne. The throne is in the form of a tabernacle or ciborium;[2] its crocketed triangular gable is framed by the inner trefoil arch of the panel, and its inner canopy is decorated with an azure star- studded “sky.” Mary supports her child with both hands. The Christ child is holding a fruit, perhaps a pomegranate,[3] in his left hand and is stretching out his right to take the small bird perched on a finger of the angel closest to him.[4] The throne is flanked on both sides by a red seraph and an azure cherub [5] and, below these, by two pairs of angels, of which the one to the far left plays a shawm—the medieval precursor of the oboe—and that on the opposite side a psaltery; the concert of angels is completed by the portative organ and the viol played by two angels kneeling in the foreground.[6] Of the four saints to the sides of the throne we can identify, to the left, Apollonia, with a tooth in her hand,[7] and, more doubtfully, -

Madonna and Child with God the Father Blessing and Angels C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Jacopo di Cione Florentine, c. 1340 - c. 1400? Madonna and Child with God the Father Blessing and Angels c. 1370/1375 tempera on panel painted surface: 139.8 × 67.5 cm (55 1/16 × 26 9/16 in.) overall: 141.2 × 69 × 1.5 cm (55 9/16 × 27 3/16 × 9/16 in.) framed: 156.8 x 84.1 x 6.7 cm (61 3/4 x 33 1/8 x 2 5/8 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1952.5.18 ENTRY The image of Mary seated on the ground (humus) accentuates the humility of the mother of Jesus, obedient ancilla Domini (Lk 1:38). The child’s gesture, both arms raised to his mother’s breast, alludes, in turn, to another theme: the suckling of her child, a very ancient aspect of Marian iconography. In the medieval interpretation, at a time when the Virgin was often considered the symbol of the Church, the motif also alluded to the spiritual nourishment offered by the Church to the faithful. [1] As is common in paintings of the period, the stars painted on Mary’s shoulders allude to the popular etymology of her name. [2] The composition—as it is developed here—presumably was based on a famous model that perhaps had originated in the shop of Bernardo Daddi (active by 1320, died probably 1348). [3] It enjoyed considerable success in Florentine painting of the second half of the fourteenth century and even later: numerous versions of the composition are known, many of which apparently derive directly from this image in the Gallery. -

Entire Triptych

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Agnolo Gaddi Florentine, c. 1350 - 1396 Madonna and Child with Saints Andrew, Benedict, Bernard, and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels [entire triptych] shortly before 1387 tempera on poplar panel left panel (overall): 197 × 80 cm (77 9/16 × 31 1/2 in.) middle panel (overall): 204 × 80 cm (80 5/16 × 31 1/2 in.) right panel (overall): 194.6 × 80 cm (76 5/8 × 31 1/2 in.) Inscription: left panel, across the bottom below the saints: S. ANDREAS AP[OSTO]L[U]S; S. BENEDICTUS ABBAS; left panel, on the book held by St. Benedict: AUSCU / LTA.O/ FILI.PR / ECEPTA / .MAGIS / [T]RI.ET.IN / CLINA.AUREM / CORDIS.T / UI[ET]A[D]MONITIONE / M.PII.PA / TRIS.LI / BENTE / R.EXCIP / E.ET.EF[FICACITER COMPLE] (Harken, O son, to the precepts of the master and incline the ear of your heart and willingly receive the admonition of the pious father and efficiently);[1] middle panel, across the bottom: AVE MARIA GRATIA PLENA DOMINUS [TECUM] (Hail, Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee; from Luke 1:28); middle panel, on the book held by the Redeemer in the gable: EGO SUM / A[ET] O PRINCI / PIU[M] [ET] FINIS / EGO SUM VI / A. VERITAS / [ET] VITA (I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, I am the way, the truth, and the life; from John 14:6; Revelations 22:13); right panel, across the bottom under the saints: S. -

Vasari: a Translation from Die Kunstliteratur (1924)

Julius von Schlosser on Vasari: a translation from Die Kunstliteratur (1924) Karl Johns - Julius Schlosser and the location of Vasari When Thomas Mann was composing Doktor Faustus and decided to have the devil make an appearance at the precise center of the manuscript, he was applying his literary irony to a phenomenon in which he had himself participated, which affected his life directly, and threatened those of his wife and children.1 When Julius Schlosser made Giorgio Vasari the isolated subject of Book Five of his Kunstliteratur, he was also describing a certain development in idiosyncratic literary terms and placing a figure at the center who could not ultimately be applauded according to the terms of his ‘Kunstliteratur’. Unlike the world of Adrian Leverkühn, Schlosser, who was felicitously described in a 1939 obituary as ‘an anachronism in the very best sense of the term’, had developed his concept of the literature of art ‘Kunstliteratur’ independently of the trends of the time. Indeed, his most ambitious essays had included a systematic refutation of the flawed premises of various types of scholarly writings about earlier art then flourishing. Formalism and undue abstraction were then exciting popular interest and drawing unusual numbers of auditors into academic lecture halls. The burgeoning literature of dissertations was being roundly criticized. In this period of emotional nationalism and rising fascism, his development of the concept of ‘Kunstliteratur’ served to stress the importance of objectivity in historical scholarship independently of anything one might feel. To create such a footing it would be necessary in his ‘classic’ book to clarify the entire emergence of the academic discipline of the history of art.