Embodied Resistance: a Historiographic Intervention Into the Performance of Queer Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. MAKING COMMUNITY: THE PLACES AND15 SPACES OF LGBTQ COLLECTIVE IDENTITY FORMATION Christina B. Hanhardt Introduction In the summer of 2012, posters reading "MORE GRINDR=FEWER GAY BARS” appeared taped to signposts in numerous gay neighborhoods in North America—from Greenwich Village in New York City to Davie Village in Vancouver, Canada.1 The signs expressed a brewing fear: that the popularity of online lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social media—like Grindr, which connects gay men based on proximate location—would soon replace the bricks-and-mortar institutions that had long facilitated LGBTQ community building. -

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk Riya Kalra Junior Division Individual Exhibit Student-composed words: 499 Process paper: 500 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Black, Jason E., and Charles E. Morris, compilers. An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk's Speeches and Writings. University of California Press, 2013. This book is a compilation of Harvey Milk's speeches and interviews throughout his time in California. These interviews describe his views on the community and provide an idea as to what type of person he was. This book helped me because it gave me direct quotes from him and allowed me to clearly understand exactly what his perspective was on major issues. Board of Supervisors in January 8, 1978. City and County of San Francisco, sfbos.org/inauguration. Accessed 2 Jan. 2019. This image is of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from the time Harvey Milk was a supervisor. This image shows the people who were on the board with him. This helped my project because it gave a visual of many of the key people in the story of Harvey Milk. Braley, Colin E. Sharice Davids at a Victory Party. NBC, 6 Nov. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/sharice-davids-lesbian-native-american-makes- political-history-kansas-n933211. Accessed 2 May 2019. This is an image of Sharcie Davids at a victory party after she was elected to congress in Kansas. This image helped me because ti provided a face to go with he quote that I used on my impact section of board. California State, Legislature, Senate. Proposition 6. -

Jeff Sessions: a History of Anti-Lgbtq Actions Letter from Judy Shepard

JEFF SESSIONS: A HISTORY OF ANTI-LGBTQ ACTIONS LETTER FROM JUDY SHEPARD DEAR FRIENDS, Since his nomination to U.S. Attorney General by President-elect Trump, Senator Jeff Sessions’ record on civil rights and criminal justice has raised a serious question for the American public: is Senator Sessions fit to serve as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer? The answer is a very simple and very clear, no. In 1998 my son, Matthew, was murdered because he was gay, a brutal hate crime that continues to resonate around the world even now. Following Matt’s death, my husband, Dennis, and I worked for the next 11 years to garner support for the federal Hate Crimes Prevention Act. We were fortunate to work alongside members of Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, who championed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act with the determination, compassion, and vision to match ours as the parents of a child targeted for simply wanting to be himself. Senator Jeff Sessions was not one of these members. In fact, Senator Sessions strongly opposed the hate crimes bill -- characterizing hate crimes as mere “thought crimes.” Unfortunately, Senator Sessions believes that hate crimes are, what he describes as, mere “thought crimes.” My son was not killed by “thoughts” or because his murderers said hateful things. My son was brutally beaten my son with the butt of a .357 magnum pistol, tied him to a fence, and left him to die in freezing temperatures because he was gay. Senator Sessions’ repeated efforts to diminish the life-changing acts of violence covered by the Hate Crimes Prevention Act horrified me then, as a parent who knows the true cost of hate, and it terrifies me today to see 2 HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN | 1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. -

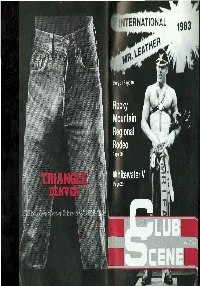

Clubscene-Jun83.Compressed.Pdf

C") Q) 0: oCl!, Q) c Q) (J (J) ..c ::l G Q) c Q) (J (J) ..c ::l G C\I Q) 0> oCl!, CONTENTS 5'. \-EP-"t"'e.;. _ • .cLUB ·--<-'r~. ..6"CENE •• ISSUE #11 '•. \~:l<i ~ ·~ l.{. ~"oj' Club News Pg. 8 International Mr. Leather '83 Pg. 16 Whitewater Weekend V Pg.23 J. Colt Thomas-International Mr. Leather '83 Rocky Mountain Regional Rodeo Pg.30 Sponsored by Officers Club-Houston Photo by I.M.L. Studios Club Calendar Pg.36 FOR THE ANIMAL OFFICES Kansas City IN YOU .... 3317 Montrose, Sui.te 1087 Burt Holderman (816)587·9941 Houston, Texas 77006 Minneapolis (713) 529-7620 Dan VanGuilder. (612) 872·9218 New Orleans PUBLISHERS .... .Alan LipkinlDan Mciver Wally Sherwood (504) 368-1805 Phoenix EDITOR .. .. Gerry "G. w." Webster Jerry Zagst (602) 266-2287 ART DIRECTOR. .... .Ty Davison FEATURE WRITERS TYPESETTER .. .Lee Christensen Fledermaus (713) 466-3224 Courtesy of Dungeon Master REPRESENTATIVE·AT·LARGE .Bill Green OFFICIALLY SANCTION ED ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Mid·America Conference of Clubs Dan Mciver (713) 529-7620 ADVERTISING AND EDITORIAL Atlanta Dale Scholes (404) 284·4370 The official views of this newsmagazine are expressed only in editorials. Opinions expressed in by-lined cot- (404) 872-0209 umns,letters and cartoons are those of the.wrlters and Chicago artists and do not necessarily represent the opinions Chuck Kiser. (312) 751·1640 of CLUB SCENE. Cleveland Publication of the name or photograph of any person or Tony Silwaru & organization in articles or advertising in CLUB SCENE Ron Criswell (216) 228·2631 is not to be construed as any indication of the sexual Corpus Christi orientation of such person or organization. -

Directory P&E 2021X Copy with ADS.Indd

Annual Directory of Producers & Engineers Looking for the right producer or engineer? Here is Music Connection’s 2020 exclusive, national list of professionals to help connect you to record producers, sound engineers, mixers and vocal production specialists. All information supplied by the listees. AGENCIES Notable Projects: Alejandro Sanz, Greg Fidelman Notable Projects: HBO seriesTrue Amaury Guitierrez (producer, engineer, mixer) Dectective, Plays Well With Others, A440 STUDIOS Notable Projects: Metallica, Johnny (duets with John Paul White, Shovels Minneapolis, MN JOE D’AMBROSIO Cash, Kid Rock, Reamonn, Gossip, and Rope, Dylan LeBlanc) 855-851-2440 MANAGEMENT, INC. Slayer, Marilyn Manson Contact: Steve Kahn Studio Manager 875 Mamaroneck Ave., Ste. 403 Tucker Martine Email: [email protected] Mamaroneck, NY 10543 Web: a440studios.com Ryan Freeland (producer, engineer, mixer) facebook.com/A440Studios 914-777-7677 (mixer, engineer) Notable Projects: Neko Case, First Aid Studio: Full Audio Recording with Email: [email protected] Notable Projects: Bonnie Raitt, Ray Kit, She & Him, The Decemberists, ProTools, API Neve. Full Equipment list Web: jdmanagement.com LaMontagne, Hugh Laurie, Aimee Modest Mouse, Sufjan Stevens, on website. Mann, Joe Henry, Grant-Lee Phillips, Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros, Promotional Videos (EPK) and concept Isaiah Aboln Ingrid Michaelson, Loudon Wainwright Mavis Staples for bands with up to 8 cameras and a Jay Dufour III, Rodney Crowell, Alana Davis, switcher. Live Webcasts for YouTube, Darryl Estrine Morrissey, Jonathan Brooke Thom Monahan Facebook, Vimeo, etc. Frank Filipetti (producer, engineer, mixer) Larry Gold Noah Georgeson Notable Projects: Vetiver, Devendra AAM Nic Hard (composer, producer, mixer) Banhart, Mary Epworth, EDJ Advanced Alternative Media Phiil Joly Notable Projects: the Strokes, the 270 Lafayette St., Ste. -

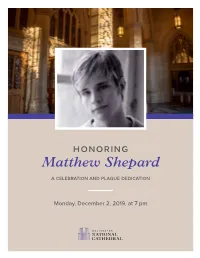

Matthew Shepard

honoring Matthew Shepard A CELEBrATion AnD PLAQUE DEDiCATion Monday, December 2, 2019, at 7 pm Welcome Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral Dennis Shepard, Matthew Shepard Foundation True Colors by Cyndi Lauper (b. 1953); arr. Deke Sharon (b. 1967) Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. Kevin Thomason, Soloist Waving Through a Window from Dear Evan Hansen; by Benj Pasek (b. 1985) and Justin Paul (b. 1985); Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. arr. Robert T. Boaz (1970–2019) You Raise Me Up by Brendan Graham (b. 1945) & Rolf Lovland (b. 1955) Brennan Connell, GenOUT; C. Paul Heins, piano The Laramie Project (moments) by Moises Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project St. Albans/National Cathedral School Thespian Society. Chris Snipe, Director Introduced by Dennis Shepard *This play contains adult language.* Matthew Sarah Muoio (Romaine Patterson) Homecoming Matthew Merril (Newsperson), Nico Cantrell (Narrator), Ilyas Talwar (Philip Dubois), Martin Villagra‑Riquelme (Harry Woods), Jorge Guajardo (Matt Galloway) Two Queers and a Catholic Priest Fiona Herbold (Narrator), Louisa Bayburtian (Leigh Fondakowski), William Barbee (Greg Pierotti and Father Roger Schmit) The people are invited to stand. The people’s responses are in bold. Opening Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral God is with us. God’s love unites us. God’s purpose steadies us. God’s Spirit comforts us. PeoPle: Blessed be God forever. O God, whose days are without end, and whose mercies cannot be numbered: Make us, we pray, deeply aware of the shortness of human life. We remember before you this day our brother Matthew and all who have lost their lives to violent acts of hate. -

Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: an Investigation of Anti- Woman Perspectives Among Leathermen

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 5-2020 Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti- Woman Perspectives among Leathermen Meredith G. F. Worthen University of Oklahoma, [email protected] Trenton M. Haltom University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Worthen, Meredith G. F. and Haltom, Trenton M., "Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti-Woman Perspectives among Leathermen" (2020). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 707. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/707 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. digitalcommons.unl.edu Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti-Woman Perspectives among Leathermen Meredith G. F. Worthen1 and Trenton M. Haltom2 1 University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA; 2 University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA Corresponding author — Meredith G. F. Worthen, University of Oklahoma, 780 Van Vleet Oval, KH 331, Norman, OK 73019; [email protected] ORCID Meredith G. F. Worthen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6765-5149 Trenton M. Haltom http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1116-4644 Abstract The Fifty Shades books and films shed light on a sexual and leather-clad subculture predominantly kept in the dark: bondage, discipline, submission, and sadomasoch- ism (BDSM). -

Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 3-24-2016 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Barry, Todd, "From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1041. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1041 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 This dissertation examines how theatre and law have worked together to produce and regulate gay male lives since the 1895 Oscar Wilde trials. I use the term “gay legal theatre” to label an interdisciplinary body of texts and performances that include legal trials and theatrical productions. Since the Wilde trials, gay legal theatre has entrenched conceptions of gay men in transatlantic culture and influenced the laws governing gay lives and same-sex activity. I explore crucial moments in the history of this unique genre: the Wilde trials; the British theatrical productions performed on the cusp of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act; mainstream gay American theatre in the period preceding the Stonewall Riots and during the AIDS crisis; and finally, the contemporary same-sex marriage debate and the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). The study shows that gay drama has always been in part a legal drama, and legal trials involving gay and lesbian lives have often been infused with crucial theatrical elements in order to legitimize legal gains for LGBT people. -

Rob Checks His List Twice

The Undergraduate Magazine Vol. V, No. 10 | January 24, 2005 House of Pain Turn Over for Sex Cosmetic Conformity My Old Friend John Lauren laments the onerous housing Thuy and Roz double up on your Anna predicts the downfall of mankind James provides a trio of reviews to application favorite subject one surgery at a time guide your listening pleasure Page 3 Page 8 Page 5 Page 7 YOU’RE NEXT, BITCH MARIAN LEE MID SEASON REPORT CARD CUDDLE ’N’ Rob checks his list twice COLLAGE ANDREW PEDERSON | BRUT FORCE ROB FORMAN | MY 13-INCH BOX WHEN I LEFT PHILADELPHIA EVERY SO OFTEN I find Desperate Housewives: Clearly the shock of the season. for Winter Break, I was hoping for myself questioning whether For some unprecedented reason—read a sense of humor— a pleasant change in climate. At I am, in fact, in a waking Desperate Housewives has managed to gain critical acclaim home in Nevada, winter usually dream. You see, I have an while being a primetime soap-opera. The witty women on means something like forty five de- acquired taste. You might Wisteria Lane have already won a Golden Globe for Best grees, 20% humidity and clear skies. even call it obscure, cultist, Comedy Series, and Teri Hatcher won for Best Lead Actress This time, however, the weather and unpopular. After all, I in a Comedy Series. Oh, and the show is the biggest new gods granted me only one week of trumpeted my love of Angel show of the season, and second overall only to the original sweet, gentle desert winter before and Wonderfalls last year CSI. -

Combating Hate Crimes: Promoting a Re- Sponsive and Responsible Role for the Federal Government

S. HRG. 106±517 COMBATING HATE CRIMES: PROMOTING A RE- SPONSIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ROLE FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON EXAMINING HOW TO PROMOTE A RESPONSIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ROLE FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ON COMBATING HATE CRIMES, FOCUSING ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND THE STATES IN COMBATING HATE CRIME, ANALY- SIS OF STATES' PROSECUTION OF HATE CRIMES, DEVELOPMENT OF A HATE CRIME LEGISLATION MODEL, AND EXISTING FEDERAL HATE CRIME LAW MAY 11, 1999 Serial No. J±106±25 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 64±861 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:28 Jun 09, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 HATE SJUD4 PsN: SJUD4 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman STROM THURMOND, South Carolina PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware JON KYL, Arizona HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin MIKE DEWINE, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York BOB SMITH, New Hampshire MANUS COONEY, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Minority Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:28 Jun 09, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 HATE SJUD4 PsN: SJUD4 C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Hatch, Hon. -

Matthew Shepard Papers

Matthew Shepard Papers NMAH.AC.1463 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2018 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Content Description.......................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Shepard, Matthew, Personal Papers, 1976-2019, undated...................... 5 Series 2: Shepard Family and The Matthew Shepard Foundation, Papers and Correspondence Received, 1998-2013, undated................................................... 12 Series 3: Tribute, Vigil, and Memorial Services, Memorabilia, and Inspired Works, 1998-2008, undated.............................................................................................. -

Combined Book Exhibit® Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Sharjah Children’s Reading Festival 2021 7___FRANKIE FROG AND THE THROATY CROAKERS: Albert Whitman & Company Hartas, Freya, Hartas, Freya. Albert Whitman & #320, 250 S. Northwest Highway, Park Ridge, Illinois USA Company, Every frog dreams of their first croak, but 60068. Frankie's croak never comes! Without it, he's not sure Tel: 847-232-2800;Fax: 847-581-0039 how he fits into the world of the pond, until one day he Email: [email protected] hears a mysterious sound from a musical instrument. Is Web: www.albertwhitman.com this another way for Frankie to make his voice heard? Frankie Frog and the Throaty Croakers is a celebration of Key Contact Information music, determination, and creativity., $16.99, HC ISBN John Quattrocchi 13: (978-0-807-52543-2) 2019, JUVENILE FICTION > General [email protected] 1___BOXCAR #1: THE BOXCAR CHILDREN: Boxcar 8___HIDE AND PEEK: Animal Time Houran, Lori Haskins, Children Warner, Gertrude Chandler, Jessell, Tim. Albert Willmore, Alex. Albert Whitman & Company, Every time Whitman & Company, The Aldens begin their adventure Bird hears a noise, she says eek! and hides her head in by making a home in a boxcar. Their goal is to stay the sand. And every time, the noise turns out to be one together, and in the process they find a grandfather., of her friends playing nearby. Can Elephant convince her $6.99, PB ISBN 13: (978-0-807-50852-7) 1942, JUVENILE that there's nothing to be scared of?, $12.99, HC ISBN FICTION > General 13: (978-0-807-57208-5) 2019, JUVENILE FICTION > General 2___BOXCAR #2: SURPRISE ISLAND: Boxcar Children 9___HOW DO YOU LIFT A LION?: Wells Of Knowledge Warner, Gertrude Chandler, Jessell, Tim.