REPORT 2006 Web.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wooltru Healthcare Fund Optical Network List Gauteng

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND OPTICAL NETWORK LIST GAUTENG PRACTICE TELEPHONE AREA PRACTICE NAME PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY OR TOWN NUMBER NUMBER ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE ACTONVILLE 084 6729235 AKASIA 7033583 MAKGOTLOE SHOP C4 ROSSLYN PLAZA, DE WAAL STREET, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5413228 AKASIA 7025653 MNISI SHOP 5, ROSSLYN WEG, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5410424 AKASIA 668796 MALOPE SHOP 30B STATION SQUARE, WINTERNEST PHARMACY DAAN DE WET, CLARINA AKASIA 012 7722730 AKASIA 478490 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 456144 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 320234 VON ABO & LABUSCHAGNE SHOP 10 KARENPARK CROSSING, CNR HEINRICH & MADELIEF AVENUE, KARENPARK AKASIA 012 5492305 AKASIA 225096 BALOYI P O J - MABOPANE SHOP 13 NINA SQUARE, GRAFENHEIM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 087 8082779 ALBERTON 7031777 GLUCKMAN SHOP 31 NEWMARKET MALL CNR, SWARTKOPPIES & HEIDELBERG ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9072102 ALBERTON 7023995 LYDIA PIETERSE OPTOMETRIST 228 2ND AVENUE, VERWOERDPARK ALBERTON 011 9026687 ALBERTON 7024800 JUDELSON ALBERTON MALL, 23 VOORTREKKER ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9078780 ALBERTON 7017936 ROOS 2 DANIE THERON STREET, ALBERANTE ALBERTON 011 8690056 ALBERTON 7019297 VERSTER $ VOSTER OPTOM INC SHOP 5A JACQUELINE MALL, 1 VENTER STREET, RANDHART ALBERTON 011 8646832 ALBERTON 7012195 VARTY 61 CLINTON ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 011 9079019 ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN 26 VOORTREKKER STREET ALBERTON 011 9078745 -

Draft Revised NWRS

1 | P a g e Task: NWRS 2 Title of document: Draft National Water Resource Strategy 2 (NWRS-2): Task leader: FC van Zyl Task team FC van Zyl, H Keuris members: Authors of Prof MN Nkondo, FC van Zyl, H Keuris, B Schreiner document: Contributors: MP Nepfumbada, H Muller Reviewers: FC van Zyl, H Keuris, MP Nepfumbada, H Muller Report status: Version 1. comprehensive Date: July 2012 Issued to: Keywords: National Water Resource Strategy National Water Resource Strategy 2 Page | i Executive Statement Water is a critical strategic natural resource. It is essential for growth and Water is a critical development, the environment, health and wellbeing of the people of South natural strategic Africa. Although this principle is generally accepted, it is not always well resource understood or appreciated. Despite the fact that South Africa is a naturally water stressed country, further challenged by the need to support growth and development as well as potential climate change impact, the resource is not receiving the priority status and attention it deserves. This situation is reflected in the manner by which this scarce resource is wasted (more than 37% water losses), polluted, degraded, inadequately financed and inappropriately strategically positioned. Paradoxically South Africa has a fairly well developed water management and infrastructure framework which has resulted in a perceived sense of water security (urban and growth areas), as well as a lack of appreciation and respect for a critical strategic resource. South Africa is facing a number of water challenges and concerns, including Water is a security of supply, environmental degradation and resource pollution. -

Fiscal Policy

3 Fiscal policy The fiscal stance presented in the 2006 Budget provides for robust growth in public services and infrastructure investment, founded on an outstanding revenue performance over the past year and the continuing strength of the financial environment. Sustained increases in expenditure on transport, education and health will support economic development, lower business costs, improve skills levels and raise living standards. The fiscal framework provides for additional resources totalling R82 billion, and a further R24 billion to replace the RSC levies. Excluding the RSC levy transfers, non-interest expenditure will increase in real terms by 7,9 per cent in 2006/07, with an average increase of 6,4 per cent over the medium- term expenditure framework (MTEF) period. Sustained economic growth has maintained the buoyancy of government revenue. Capital spending is projected to rise strongly over the medium term. The budget deficit is projected to increase to 1,5 per cent of GDP next year, and then to decline to 1,2 per cent in 2008/09. The low deficit reflects careful macroeconomic management during a time of strong commodity prices and high consumer demand. The public sector borrowing requirement is expected to grow from 0,6 per cent of GDP in 2005/06 to 2,4 per cent of GDP by 2008/09 as a result of public enterprises’ capital expenditure programmes and an increase in the main budget deficit. Overview In the past year the South African economy has registered a strong Robust consumption performance, with GDP growth of about 5 per cent expected for and investment support 2005/06. -

City Coins Post Al Medal Auction No. 68 2017

Complete visual CITY COINS CITY CITY COINS POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION NO. 68 MEDAL POSTAL POSTAL Medal AUCTION 2017 68 POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 68 CLOSING DATE 1ST SEPTEMBER 2017 17.00 hrs. (S.A.) GROUND FLOOR TULBAGH CENTRE RYK TULBAGH SQUARE FORESHORE CAPE TOWN, 8001 SOUTH AFRICA P.O. BOX 156 SEA POINT, 8060 CAPE TOWN SOUTH AFRICA TEL: +27 21 425 2639 FAX: +27 21 425 3939 [email protected] • www.citycoins.com CATALOGUE AVAILABLE ELECTRONICALLY ON OUR WEBSITE INDEX PAGES PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 2 – 3 THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1880-1881 4 – 9 by ROBERT MITCHELL........................................................................................................................ ALPHABETICAL SURNAME INDEX ................................................................................ 114 PRICES REALISED – POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 67 .................................................... 121 . BIDDING GUIDELINES REVISED ........................................................................................ 124 CONDITIONS OF SALE REVISED ........................................................................................ 125 SECTION I LOTS THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE; MEDALS ............................................. 1 – 9 SOUTHERN AFRICAN VICTORIAN CAMPAIGN MEDALS ........................................ 10 – 18 THE ANGLO BOER WAR 1899-1902: – QUEEN’S SOUTH AFRICA MEDALS ............................................................................. -

Doornkop, May 1900

Second Doornkop, May 1900 Four years later the British were back at Doornkop. That is, if one presumes the Rhodesian raiders, acting in the private interest of Rhodes and his fellow conspirators to overthrow the ZAR government, were “British”; and if one assumes a rather loose definition of the battlefield to be described. Fig 62: Boers in the field, this group at Spioenkop in the Natal Colony. Fig 63: British troops take aim, this photo taken at Colesberg in the Cape Colony. Pics: ABWM. May 1900 was towards the end of the first year of war. The South African War, also known as the Second or Anglo Boer War had started badly for Britain with a series of setbacks in October and November 1899 that saw British forces besieged at Ladysmith, Kimberley as well as Mafekeng and followed by Black Week, a series of calamities in the Cape and Natal during December 1899: Stormberg (10 December), Magersfontein (11 December) and Colenso (15 December). Over the New Year the British had recovered their posture and early in the year they had launched a general counter-offensive in both the Cape and Natal. By March Bloemfontein had fallen and Imperial forces were poised to move on the ZAR, which they reached in May. “Second Doornkop”, is a controversial battle, one which several writers have condemned as unnecessary. Field Marshal Lord Michael Carver writes in The National Army Museum Book of the Boer War that Lt Gen Ian Hamilton “engaged in what many thought a needlessly direct frontal attack. 95 ” Pakenham goes further saying the attack, when made, took some of its observers aback: “Then to the surprise of one of the brigadiers, (Maj Gen Hutton) and one of the correspondents (Churchill), Hamilton launched his two infantry brigades on a four mile wide frontal attack on the ridge.” 96 Both statements need interrogation; suffice to say the attack forms an integral part of the greater battle of Johannesburg that took place over two days in late May 1900. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Lies Hidden in the Rocks

Sivhili Injhiniyeringi June 2008 Vol 16 No 6 ONE SOLUTION TO WATER SUPPLY PROBLEMS LIES HIDDEN IN THE ROCKS P CA THE LIKELIHooD OF A GLOBAL DROUGHT IN 2009–2016 A W A R D S W I N N E R 2 0 0 7 FOR EXCELLENCE IN MAGAZINE PUBLISHING AND JOURNALISM VRESAP to be operational by November Implementation of the reserve at the Berg River Dam and Supplement Scheme Outeniqua Coast Water Situation Study 24 MONTHS TO FIFA 2010 P CA A W A R D S W I N N E R 2 0 0 7 FOR EXCELLENCE IN MAGAZINE PUBLISHING AND JOURNALISM Tshivenda ON THE COVER One of GEL’s new Beretta T46 drilling rigs installing lateral support to the Western access tunnel at the Soccer City Stadium ON THE CovER where the 2010 FIFA World Cup final will be played. This tunnel was constructed under the existing West grandstand, with Ensuring solid foundations for the FIFA supported faces of up to 9 m high; in total, World Cup’s flagship stadium 46 approximately 500 m2 lateral support was installed to three tunnels and the multi- WATER ENGINEERING OTHER PROJECTS storey parkade Potable water reservoir under construction 49 One solution to water supply problems Cape Town Terminal expansion on track 50 lies hidden in the rocks 2 Anglian Water’s biggest ever project 53 Dynamic planning process for water Recycling our roads 57 and sewer infrastructure 5 Boost for safer crane operations 55 Berg Water Project reserve releases: Traffic control centres for Limpopo 59 Implementation of the reserve at the Berg PUBLISHED BY SAICE/SAISI Block 19, Thornhill Office Park, River Dam and Supplement Scheme -

Energy and Water

ENERGY AND WATER 137 Pocket Guide to South Africa 2011/12 ENERGY AND WATER Energy use in South Africa is characterised by a high level of dependence on cheap and abundantly available coal. South Africa imports a large amount of crude oil. A limited quantity of natural gas is also available. The Department of Energy’s Energy Policy is based on the following key objectives: • ensuring energy security • achieving universal access and transforming the energy sector • regulating the energy sector • effective and efficient service delivery • optimal use of energy resources • ensuring sustainable development • promoting corporate governance. Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) The IRP lays the foundation for the country’s energy mix up to 2030, and seeks to find an appropriate balance between the expectations of different stakeholders considering a number of key constraints and risks, including: • reducing carbon emissions • new technology uncertainties such as costs, operability and lead time to build • water usage • localisation and job creation • southern African regional development and integration • security of supply. The IRP provides for a diversified energy mix, in terms of new generation capacity, that will comprise: • coal at 14% (government’s view is that there is a future for coal in the energy mix, and that it should continue research and development to find ways to clean the country’s abundant coal resources) • nuclear at 22,6% • open-cycle gas turbine at 9,2% and closed-cycle gas turbine at 5,6% • renewable energy carriers, which include hydro at 6,1%, wind at 19,7%, concentrated solar power at 2,4% and photovoltaic at 19,7%. -

Class, Race and Gender Amongst White Volunteers, 1939-1953

From War to Workplace: Class, Race and Gender amongst White Volunteers, 1939-1953 By Neil Roos Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences at the University of North West Supervisor: Dr. Tim Clynick Mafikeng, North West Province August 2001 To Dick Abstract Through a case study of the war and post-war experiences of those who volunteered to serve in the Second World War, the thesis explores aspects of the social and cultural history of white men in South Africa. The thesis begins from the premise that class and ethnicity, the major binary categories conventionally used to explain developments in white South African society, are unable to account for the history of white men who volunteered to serve in the Second World War. It argues that the history of these volunteers is best understood in the context of racist culture, which can be defined as an evolving consensus amongst whites in South Africa on the political, social and cultural primacy of whiteness. It argues that, when the call to arms came in 1939, it was answered mainly by white men from those little traditions incorporated politically into the segregationist colonial order, largely through the explicit emphases of white privilege and the cultural hegemony of whiteness. Their decision to enlist was underscored by an awareness that volunteering entailed a set of rights and duties, which centred on their expectations of post-war "social justice." Chapter three examines some of the highly idealised and implicitly racialised ways in which, during wartime, white troops expanded their understanding of social justice. -

History 1886

How many bones must you bury before you can call yourself an African? Updated December 2009 A South African Diary: Contested Identity, My Family - Our Story Part D: 1886 - 1909 Compiled by: Dr. Anthony Turton [email protected] Caution in the use and interpretation of these data This document consists of events data presented in chronological order. It is designed to give the reader an insight into the complex drivers at work over time, by showing how many events were occurring simultaneously. It is also designed to guide future research by serious scholars, who would verify all data independently as a matter of sound scholarship and never accept this as being valid in its own right. Read together, they indicate a trend, whereas read in isolation, they become sterile facts devoid of much meaning. Given that they are “facts”, their origin is generally not cited, as a fact belongs to nobody. On occasion where an interpretation is made, then the commentator’s name is cited as appropriate. Where similar information is shown for different dates, it is because some confusion exists on the exact detail of that event, so the reader must use caution when interpreting it, because a “fact” is something over which no alternate interpretation can be given. These events data are considered by the author to be relevant, based on his professional experience as a trained researcher. Own judgement must be used at all times . All users are urged to verify these data independently. The individual selection of data also represents the author’s bias, so the dataset must not be regarded as being complete. -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

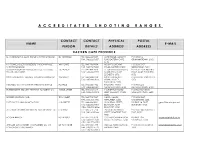

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714