Comparative Transcriptomics of Gymnosporangium Spp. Teliospores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pear Trellis Rust, a New Disease

Natter’s Notes summer. By mid-summer, Pear Trellis Rust, a tiny black dots (pycnia) appear in the center of the new disease leaf spots.” [Fig 3] By late Jean R. Natter summer, brown, blister-like swellings form on the lower Recently, Pear Trellis Rust leaf surface just beneath (Gymnosporangium the leaf spots. This is sabinae) became the followed by the newest contributor to this development of acorn- hodge-podge-let’s-try- shaped structures (aecia) everything year. During with open, trellis-like sides 2016, the first case of pear Fig 1: Pear trellis rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) on the top that give this disease its trellis rust was reported in leaf surface of edible pear tree; Multnomah County, OR. (Client common name. (Fig 4) the northern section of the image; 2017-09) Aeciospores produced within Willamette Valley, that on a Bartlett pear growing in the aecia are wind-blown to susceptible juniper Milwaukie, Clackamas County. (See “Pear Trellis hosts where they can cause infections on young Rust: First Report in Oregon” Metro MG Newsletter, shoots. These spores are released from late summer January 2016; until leaf drop.” (“Pear Trellis Rust, http://extension.oregonstate.edu/mg/metro/sites/d Gymnosporangium sabinae” efault/files/dec_2016_mg_newsletter_12116.pdf. (http://www.ladybug.uconn.edu/FactSheets/pear- Then, in mid-September 2017, an inquiry about a trellis-rust_6_2329861430.pdf) pear leaf problem in Multnomah County was submitted to Ask an Expert. [Fig 1; Fig 2] Yes, it’s Signs on affected alternate host junipers are difficult another fruiting pear tree infected with trellis rust. It to detect. -

Sex Pheromone of Conophthorus Ponderosae (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in a Coastal Stand of Western White Pine (Pinaceae)

SEX PHEROMONE OF CONOPHTHORUS PONDEROSAE (COLEOPTERA: SCOLYTIDAE) IN A COASTAL STAND OF WESTERN WHITE PINE (PINACEAE) \ ._ DANIEL R MILLER’ j I,’ . D.R. Miller Consulting Services, 1201-13353 108th Avenue, Surrey, British Columbia, ’ Canada V3T ST5 HAROLD D PIERCE JR Department of Chemistry. Simon Fraser University. Burnaby. British Columbia. Canada V5A IS.6 PETER DE GROOT Great Lakes Forestry Centre, Natural Resources Canada, P.O. Box 490. Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada P6A 5M7 NICOLE JEANS-WILLIAMS Centre for Environmental Biology, Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby. British Columbia. Canada V5A IS6 ROBB BENNEI-~ Tree Improvement Branch. British Columbia Ministry of Forests. 7380 Puckle Road. Saanichton, British Columbia. Canada V8M 1 W4 and JOHN H BORDEN Centre for Environmental Biology, Department of Biological Sciences. Simon Fraser University. Burnaby, British Columbia. Canada V5A IS6 The Canadian Entomologist 132: 243 - 245 (2000) An isolated stand of western white pine, Pinus monticola Dougl. ex D. Don, on Texada Island (49”4O’N, 124”1O’W), British Columbia, is extremely valuable as a seed-production area for progeny resistant to white pine blister rust, Cronartium ribicola J.C. Fisch. (Cronartiaceae). During the past 5 years, cone beetles, Conophthorus ponderosae Hopkins (= C. monticolae), have severely limited crops of western white pine seed from the stand. Standard management options for cone beetles in seed orchards are not possible on Texada Island. A control program in wild stands such as the one on Texada Island requires alternate tactics such as a semiochemical-based trapping program. Females of the related species, Conophthorus coniperda (Schwarz) and Conophthorus resinosae Hopkins, produce (+)-pityol, (2R,5S)-2-( 1 -hydroxyl- 1 -methylethyl)-5-methyl-tetrahydrofuran, a sex pheromone that attracts males of both species (Birgersson et al. -

Introduction to Neotropical Entomology and Phytopathology - A

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT – Vol. VI - Introduction to Neotropical Entomology and Phytopathology - A. Bonet and G. Carrión INTRODUCTION TO NEOTROPICAL ENTOMOLOGY AND PHYTOPATHOLOGY A. Bonet Department of Entomology, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Mexico G. Carrión Department of Biodiversity and Systematic, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Mexico Keywords: Biodiversity loss, biological control, evolution, hotspot regions, insect biodiversity, insect pests, multitrophic interactions, parasite-host relationship, pathogens, pollination, rust fungi Contents 1. Introduction 2. History 2.1. Phytopathology 2.1.1. Evolution of the Parasite-Host Relationship 2.1.2. The Evolution of Phytopathogenic Fungi and Their Host Plants 2.1.3. Flor’s Gene-For-Gene Theory 2.1.4. Pathogenetic Mechanisms in Plant Parasitic Fungi and Hyperparasites 2.2. Entomology 2.2.1. Entomology in Asia and the Middle East 2.2.2. Entomology in Ancient Greece and Rome 2.2.3. New World Prehispanic Cultures 3. Insect evolution 4. Biodiversity 4.1. Biodiversity Loss and Insect Conservation 5. Ecosystem services and the use of biodiversity 5.1. Pollination in Tropical Ecosystems 5.2. Biological Control of Fungi and Insects 6. The future of Entomology and phytopathology 7. Entomology and phytopathology section’s content 8. ConclusionUNESCO – EOLSS Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical SketchesSAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary Insects are among the most abundant and diverse organisms in terrestrial ecosystems, making up more than half of the earth’s biodiversity. To date, 1.5 million species of organisms have been recorded, although around 85% of potential species (some 10 million) have not yet been identified. In the case of the Neotropics, although insects are clearly a vital element, there are many families of organisms and regions that are yet to be well researched. -

The Pathogenicity and Seasonal Development of Gymnosporangium

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1931 The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa Donald E. Bliss Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, Botany Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Bliss, Donald E., "The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa " (1931). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14209. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14209 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

ISB: Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants

Longleaf Pine Preserve Plant List Acanthaceae Asteraceae Wild Petunia Ruellia caroliniensis White Aster Aster sp. Saltbush Baccharis halimifolia Adoxaceae Begger-ticks Bidens mitis Walter's Viburnum Viburnum obovatum Deer Tongue Carphephorus paniculatus Pineland Daisy Chaptalia tomentosa Alismataceae Goldenaster Chrysopsis gossypina Duck Potato Sagittaria latifolia Cow Thistle Cirsium horridulum Tickseed Coreopsis leavenworthii Altingiaceae Elephant's foot Elephantopus elatus Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Oakleaf Fleabane Erigeron foliosus var. foliosus Fleabane Erigeron sp. Amaryllidaceae Prairie Fleabane Erigeron strigosus Simpson's rain lily Zephyranthes simpsonii Fleabane Erigeron vernus Dog Fennel Eupatorium capillifolium Anacardiaceae Dog Fennel Eupatorium compositifolium Winged Sumac Rhus copallinum Dog Fennel Eupatorium spp. Poison Ivy Toxicodendron radicans Slender Flattop Goldenrod Euthamia caroliniana Flat-topped goldenrod Euthamia minor Annonaceae Cudweed Gamochaeta antillana Flag Pawpaw Asimina obovata Sneezeweed Helenium pinnatifidum Dwarf Pawpaw Asimina pygmea Blazing Star Liatris sp. Pawpaw Asimina reticulata Roserush Lygodesmia aphylla Rugel's pawpaw Deeringothamnus rugelii Hempweed Mikania cordifolia White Topped Aster Oclemena reticulata Apiaceae Goldenaster Pityopsis graminifolia Button Rattlesnake Master Eryngium yuccifolium Rosy Camphorweed Pluchea rosea Dollarweed Hydrocotyle sp. Pluchea Pluchea spp. Mock Bishopweed Ptilimnium capillaceum Rabbit Tobacco Pseudognaphalium obtusifolium Blackroot Pterocaulon virgatum -

Pear Trellis Rust

Dr. Yonghao Li Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8601 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes PEAR TRELLIS RUST Pear trellis rust (European pear rust) is one premature defoliation, significant diebacks, of most devastating diseases on fruit and and reduced tree vigour (Figure 1). ornamental pear trees in Europe. In the United States, since the disease was first SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSTICS reported in the Bellingham, WA in 1997, it The disease affects pear and juniper plants, has moved from the west coast to east coast. which is the alternate host of the fungal In Connecticut, pear trellis rust was first pathogen Gymnosporangium sabinae. On reported in 2012. Although the disease is pear trees, the disease mainly damages considered cosmetic on pear trees, heavy and leaves although twigs and fruit can also be repeated infections due to wet spring infected. The initial symptom appears as weather conditions may result in severe yellow spots on the upper side of young leaves in the spring. Lesions become reddish orange in color and expand up to 3/4 inch in diameter (Figure 2). By mid summer, small black dots (spermagonia) form in the center of the spot on the upper side of leaves. And then, light brown, Figure 1. Browning of leaves and early Figure 2. Reddish-brown lesions on the defoliation of heavily infected pear trees in upper- (left) and lower-side (right) of the early summer leaf acorn-shaped structures (aecia) form on the differences in susceptibility between under side of the leaf directly below the varieties. -

Population Biology of Switchgrass Rust

POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) By GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Bachelor of Science in Biotechnology Escuela Politécnica del Ejército (ESPE) Quito, Ecuador 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 2014 POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Thesis Approved: Dr. Stephen Marek Thesis Adviser Dr. Carla Garzon Dr. Robert M. Hunger ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their guidance and support, I express sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Marek, who has supported thought my thesis with his patience and knowledge whilst allowing me the room to work in my own way. One simply could not wish for a better or friendlier supervisor. I give special thanks to M.S. Maxwell Gilley (Mississippi State University), Dr. Bing Yang (Iowa State University), Arvid Boe (South Dakota State University) and Dr. Bingyu Zhao (Virginia State), for providing switchgrass rust samples used in this study and M.S. Andrea Payne, for her assistance during my writing process. I would like to recognize Patricia Garrido and Francisco Flores for their guidance, assistance, and friendship. To my family and friends for being always the support and energy I needed to follow my dreams. iii Acknowledgements reflect the views of the author and are not endorsed by committee members or Oklahoma State University. Name: GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Date of Degree: JULY, 2014 Title of Study: POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Major Field: ENTOMOLOGY AND PLANT PATHOLOGY Abstract: Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) is a perennial warm season grass native to a large portion of North America. -

Master Thesis

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Uppsala 2011 Taxonomic and phylogenetic study of rust fungi forming aecia on Berberis spp. in Sweden Iuliia Kyiashchenko Master‟ thesis, 30 hec Ecology Master‟s programme SLU, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Iuliia Kyiashchenko Taxonomic and phylogenetic study of rust fungi forming aecia on Berberis spp. in Sweden Uppsala 2011 Supervisors: Prof. Jonathan Yuen, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Anna Berlin, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Examiner: Anders Dahlberg, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Credits: 30 hp Level: E Subject: Biology Course title: Independent project in Biology Course code: EX0565 Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Key words: rust fungi, aecia, aeciospores, morphology, barberry, DNA sequence analysis, phylogenetic analysis Front-page picture: Barberry bush infected by Puccinia spp., outside Trosa, Sweden. Photo: Anna Berlin 2 3 Content 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………. 6 1.1 Life cycle…………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.2 Hyphae and haustoria………………………………………………………………... 9 1.3 Rust taxonomy……………………………………………………………………….. 10 1.3.1 Formae specialis………………………………………………………………. 10 1.4 Economic importance………………………………………………………………... 10 2 Materials and methods……………………………………………………………... 13 2.1 Rust and barberry -

Basidiomycota

BASIDIOMYCOTA 1. Class Uredinoiomycetes –Order Uredinales - The Rusts 2. Class Ustomycetes -Order Ustilaginales - The Smuts 3. Class Basidiomycetes- Order Agaricales - the boletes, gilled mushrooms - inky caps, oyster mushrooms, etc. Gilled mushrooms Inky caps The Rusts These are obligate parasites. Generally these require two host to complete their lifecycle. Primary hosts – the host on which basidia and basidiospores are produced. Alternate host – the other host in the life cycle on which spermagonia and aecia are produced. Alternative host – the host that a pathogen can infect in place of the primary or alternate hosts. Heteroecious – organisms with a primary and alternate host. Autoecious – organisms that have only a single (primary) host. Macrocyclic rust – long cycle rust. Produce all 5 spore types. Demicyclic rust – medium cycle rust. Omits uredia. Microcyclic rust – short cycle rusts. Produces basidiospores, teliospores and spermatia. Stem Rust of Wheat caused by Puccinia graminis Reduces yield and quality of grain fungus causes lesions or pustules on wheat stems. Management . remove alternate host (i.e., barberry); . use resistant cultivars of wheat Cedar-Apple Rust caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae Apples become deformed and ugly; fruit size reduced due to damage to foliage – Management . removal of cedar trees, which serves as the alternate host; . spray apple trees with fungicides, and . use rust-resistant apple trees The Smuts Corn smut caused by Ustilago maydis Galls develop on male and female (ear) inflorescences. No major methods of control recommended; tends to be a chronic but relatively insignificant disease. Loose smut of cereals by Ustilago avenae, U. nuda, and U. tritici Flowering parts of plants develop spore-filled galls (teliospores) – infected seed treated with fungicides before planting; use of certified smut-free seeds and systemic fungicides; hot-water treatment of seed to kill fungus. -

Saprophytic Growth of the Alder Rust Fungus Melampsoridium Hiratsukanum on Artificial Media

fungal biology 119 (2015) 568e579 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funbio Saprophytic growth of the alder rust fungus Melampsoridium hiratsukanum on artificial media Salvatore MORICCA*, Beatrice GINETTI DISPAA, Dipartimento di Scienze delle Produzioni Agroalimentari e dell’Ambiente, Universita di Firenze, Piazzale delle Cascine 28, I 50144 Firenze, Italy article info abstract Article history: The first axenic culture of a free living saprophytic stage of the exotic rust fungus Melamp- Received 7 August 2014 soridium hiratsukanum is reported. Colonies were obtained from one-celled, dikaryotic ure- Received in revised form diniospores on eight nutrient media out of twelve. Modified Harvey and Grasham (HG) and 12 February 2015 Schenk and Hildebrandt (HS) media HG1 and SH1 and their bovine serum albumin (BSA)- Accepted 3 March 2015 enriched derivatives gave abundant mycelial growth, but modified Murashige and Skoog Available online 14 March 2015 (MS) QMS media and their BSA-enriched modifications performed poorly, colony growth Corresponding Editor: being low on QMS-1 and QMS1þBSA, and nil on QMS-5 and QMS-6, with or without BSA. Paul Birch Colonies initially grew poorly when subcultured for one month in purity, but much better after re-transfer to fresh media later: presumably because only the most exploitative geno- Keywords: types survived, best able to cope with an uncongenial medium. Stabilised cultures sur- Exotic rust vived, and remained vegetative, but only few reproductive colonies produced spore-like Invasive species bodies. Though the agarised medium remains an inhospitable environment for this biotro- In vitro growth phic parasite, it is shown that non-living media can nevertheless sustain the growth and Sporulation sporulation of this fungus outside its natural hosts and habitat. -

Geospatial Variation of an Invasive Forest Disease and the Effects on Treeline Dynamics in the Rocky Mountains

Geospatial Variation of an Invasive Forest Disease and the Effects on Treeline Dynamics in the Rocky Mountains Emily Katherine Smith-McKenna Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Geospatial and Environmental Analysis Lynn M. Resler, Chair George P. Malanson Stephen P. Prisley Laurence W. Carstensen Jr. October 2, 2013 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Treeline, Whitebark Pine, Pinus albicaulis, Blister Rust, Rocky Mountains, spatial pattern, GIS, GPS, DEM, Agent-Based Model Copyright 2013, Emily K. Smith-McKenna Geospatial Variation of an Invasive Forest Disease and the Effects on Treeline Dynamics in the Rocky Mountains Emily Katherine Smith-McKenna ABSTRACT Whitebark pine is an important keystone and foundation species in western North American mountain ranges, and facilitates tree island development in Rocky Mountain treelines. The manifestation of white pine blister rust in the cold and dry treelines of the Rockies, and the subsequent infection and mortality of whitebark pines raises questions as to how these extreme environments harbor the invasive disease, and what the consequences may be for treeline dynamics. This dissertation research comprises three studies that investigate abiotic factors influential for blister rust infection in treeline whitebark pines, how disease coupled with changing climate may affect whitebark pine treeline dynamics, and the connection between treeline spatial patterns and disease. The first study examined the spatial variation of blister rust infection in two whitebark pine treeline communities, and potential topographic correlates. Using geospatial and field approaches to generate high resolution terrain models of treeline landscapes, microtopography associated with solar radiation and moisture were found most influential to blister rust infection in treeline whitebark pines. -

Cedar Apple Rust

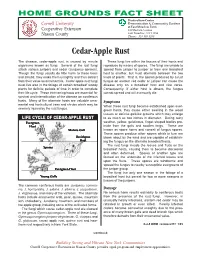

HOME GROUNDS FACT SHEET Horticulture Center Cornell University Demonstration & Community Gardens at East Meadow Farm Cooperative Extension 832 Merrick Avenue East Meadow, NY 11554 Nassau County Phone: 516-565-5265 Cedar-Apple Rust The disease, cedar-apple rust, is caused by minute These fungi live within the tissues of their hosts and organisms known as fungi. Several of the rust fungi reproduce by means of spores. The fungi are unable to attack various junipers and cedar (Juniperus species). spread from juniper to juniper or from one broadleaf Though the fungi usually do little harm to these trees host to another, but must alternate between the two and shrubs, they make them unsightly and thus detract kinds of plants. That is, the spores produced by a rust from their value as ornamentals. Cedar-apple rust fungi fungus on eastern red cedar or juniper can cause the must live also in the foliage of certain broadleaf woody disease only on a broadleaf host and vice versa. plants for definite periods of time in order to complete Consequently, if either host is absent, the fungus their life cycle. These intervening hosts are essential for cannot spread and will eventually die. survival and intensification of the disease on coniferous hosts. Many of the alternate hosts are valuable orna- Symptoms mental and horticultural trees and shrubs which may be When these rust fungi become established upon ever- severely injured by the rust fungus. green hosts, they cause either swelling in the wood tissues or definite gall-like growths which may enlarge LIFE CYCLE OF CEDAR-APPLE RUST to as much as two inches in diameter.