Title of Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Russia and Ukraine's Use of the Eurovision Song

Lund University FKVK02 Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Peace and Conflict Studies Supervisor: Fredrika Larsson The Battle of Eurovision A case study of Russia and Ukraine’s use of the Eurovision Song Contest as a cultural battlefield Character count: 59 832 Julia Orinius Welander Abstract This study aims to explore and analyze how Eurovision Song Contest functioned as an alternative – cultural – battlefield in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict over Crimea. With the use of soft power politics in warfare as the root of interest, this study uses the theories of cultural diplomacy and visual international relations to explore how images may be central to modern-day warfare and conflicts as the perception of. The study has a theory-building approach and aims to build on the concept of cultural diplomacy in order to explain how the images sent out by states can be politized and used to conduct cultural warfare. To explore how Russia and Ukraine used Eurovision Song Contest as a cultural battlefield this study uses the methodological framework of a qualitative case study with the empirical data being Ukraine’s and Russia’s Eurovision Song Contest performances in 2016 and 2017, respectively, which was analyzed using Roland Barthes’ method of image analysis. The main finding of the study was that both Russia and Ukraine used ESC as a cultural battlefield on which they used their performances to alter the perception of themselves and the other by instrumentalizing culture for political gain. Keywords: cultural diplomacy, visual IR, Eurovision Song Contest, Crimea Word count: 9 732 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ -

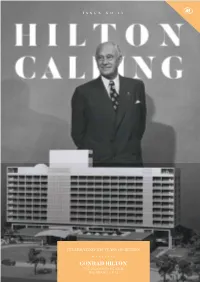

CONRAD HILTON the VISIONARY BEHIND the BRAND – P.12 Visit → Businessventures.Com.Mt

ISSUE NO.13 CELEBRATING 100 YEARS OF HILTON CONRAD HILTON THE VISIONARY BEHIND THE BRAND – P.12 Visit → businessventures.com.mt Surfacing the most beautiful spaces Marble | Quartz | Engineered Stone | Granite | Patterned Tiles | Quartzite | Ceramic | Engineered Wood Halmann Vella Ltd, The Factory, Mosta Road, Lija. LJA 9016. Malta T: (+356) 21 433 636 E: [email protected] www.halmannvella.com Surfacing the most beautiful spaces Marble | Quartz | Engineered Stone | Granite | Patterned Tiles | Quartzite | Ceramic | Engineered Wood Halmann Vella Ltd, The Factory, Mosta Road, Lija. LJA 9016. Malta T: (+356) 21 433 636 E: [email protected] www.halmannvella.com FOREWORD Hilton Calling Dear guests and friends of the Hilton Malta, Welcome to this very special edition of our magazine. The 31st of May 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the opening of the first Hilton hotel in the world, in Cisco, Texas, in the United States of America. Since that milestone date in 1919, the brand has gone from strength to strength. Globally, there are currently just under 5700 hotels, in more than 100 countries, under a total of 17 brands, with new properties opening every day. Hilton has been EDITOR bringing memorable experiences to countless guests, clients and team members Diane Brincat for a century, returned value to the owners who supported it, and made a strongly positive impact on the various communities in which it operates. We at the Hilton MAGAZINE COORDINATOR Malta are proud to belong to this worldwide family, and to join in fulfilling its Rebecca Millo mission – in Conrad Hilton’s words, to ‘fill the world with the light and warmth of hospitality’ – for at least another 100 years. -

Exam Mishap As Students Given Test with Answers Attached

ISSUE 1633 FRIDAY 6th MAY 2016 The Student Newspaper of Imperial College London Imperial 3rd most We need to talk about prestigious uni in UK Israel PAGE 4 NEWS PAGE 7 COMMENT EXAM MISHAP AS STUDENTS GIVEN TEST WITH ANSWERS AT TACHED • First year geophysics students surprised to open file that included solutions • Test will be replaced with coursework unit th PAGE 2 THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON FRIDAY 6 MAY 2016 felixonline.co.uk [email protected] Contents A word from the Editor News 3 Editor-in-Chief Grace Rahman Comment 6 his editorial has been a you’re too frightened to put your News Editor Matt Johnston Science 9 long time coming, and name to it. I know you’ve all been Nowadays, you do have to log in Comment Editors Music 12 waiting for this: the to comment on articles. You can still Tessa Davey and Vivien Hadlow FELIX view on the Labour anti- remain anonymous to other FELIX Science Editors Film 18 semitismT row. Just kidding! I can’t website surfers, but our webmasters Jane Courtnell and Lef Apostolakis think of anything I’d want to give will know who you are. You can still Arts 22 my inexperienced view on less, up or downvote comments without Arts Editors except maybe last week’s sex toy being logged in, so the people have Indira Mallik, Jingjie Cheng and Max Falkenberg TV 25 review. free reign to decide whether they What do you get when you agree with you or not. So yes, you Music Editor Clubs & Societies 27 combine controversial, emotive can still post bile. -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

The Contestants the Contestants

The Contestants The Contestants CYPRUS GREECE Song: Gimme Song: S.A.G.A.P.O (I Love You) Performer: One Performer: Michalis Rakintzis Music: George Theofanous Music: Michalis Rakintzis Lyrics: George Theofanous Lyrics: Michalis Rakintzis One formed in 1999 with songwriter George Michalis Rakintzis is one of the most famous Theofanous, Constantinos Christoforou, male singers in Greece with 16 gold and Dimitris Koutsavlakis, Filippos Constantinos, platinum records to his name. This is his second Argyris Nastopoulos and Panos Tserpes. attempt to represent his country at the Eurovision Song Contest. The group’s first CD, One, went gold in Greece and platinum in Cyprus and their maxi-single, 2001-ONE went platinum. Their second album, SPAIN Moro Mou was also a big hit. Song: Europe’s Living A Celebration Performer: Rosa AUSTRIA Music: Xasqui Ten Lyrics:Toni Ten Song: Say A Word Performer: Manuel Ortega Spain’s song, performed by Rosa López, is a Music:Alexander Kahr celebration of the European Union and single Lyrics: Robert Pfluger currency. Rosa won the hearts of her nation after taking part in the reality TV show Twenty-two-year-old Manuel Ortega is popular Operacion Triunfo. She used to sing at in Austria and his picture adorns the cover of weddings and baptisms in the villages of the many teenage magazines. He was born in Linz Alpujarro region and is now set to become one and, at the age of 10, he became a member of of Spain’s most popular stars. the Florianer Sängerknaben, one of the oldest boys’ choirs in Austria. CROATIA His love for pop music brought him back to Linz where he joined a group named Sbaff and, Song: Everything I Want by the age of 15, he had performed at over 200 Performer:Vesna Pisarovic concerts. -

REFLECTIONS 148X210 UNTOPABLE.Indd 1 20.03.15 10:21 54 Refl Ections 54 Refl Ections 55 Refl Ections 55 Refl Ections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS MERCI CHÉRIE – MERCI, JURY! AUSGABE 2015 | ➝ Es war der 5. März 1966 beim Grand und belgischen Hitparade und Platz 14 in Prix d’Eurovision in Luxemburg als schier den Niederlanden. Im Juni 1966 erreichte Unglaubliches geschah: Die vielbeachte- das Lied – diesmal in Englisch von Vince te dritte Teilnahme von Udo Jürgens – Hill interpretiert – Platz 36 der britischen nachdem er 1964 mit „Warum nur war- Single-Charts. um?“ den sechsten Platz und 1965 mit Im Laufe der Jahre folgten unzähli- SONG CONTEST CLUBS SONG CONTEST 2015 „Sag‘ ihr, ich lass sie grüßen“ den vierten ge Coverversionen in verschiedensten Platz belegte – bescherte Österreich end- Sprachen und als Instrumentalfassungen. Wien gibt sich die Ehre lich den langersehnten Sieg. In einem Hier bestechen – allen voran die aktuelle Teilnehmerfeld von 18 Ländern startete Interpretation der grandiosen Helene Fi- der Kärntner mit Nummer 9 und konnte scher – die Versionen von Adoro, Gunnar ÖSTERREICHISCHEN schließlich 31 Jurypunkte auf sich verei- Wiklund, Ricky King und vom Orchester AUSSERDEM nen. Ein klarer Sieg vor Schweden und Paul Mauriat. Teilnehmer des Song Contest 2015 – Rückblick Grand Prix 1967 in Wien Norwegen, die sich am Podest wiederfan- Hier sieht man das aus Brasilien stam- – Vorentscheidung in Österreich – Das Jahr der Wurst – Österreich und den. mende Plattencover von „Merci Cherie“, DAS MAGAZIN DES der ESC – u.v.m. Die Single erreichte Platz 2 der heimi- das zu den absoluten Raritäten jeder Plat- schen Single-Charts, Platz 2 der deutschen tensammlung zählt. DIE LETZTE SEITE ections | Refl AUSGABE 2015 2 Refl ections 2 Refl ections 3 Refl ections 3 Refl ections INHALT VORWORT PRÄSIDENT 4 DAS JAHR DER WURST 18 GRAND PRIX D'EUROVISION 60 HERZLICH WILLKOMMEN 80 „Building bridges“ – Ein Lied Pop, Politik, Paris. -

Gianluca Jer;A’ Jpo;;I Lil Malta Mal-Aqwa G[Axra Minn Noel D’Anastas – [email protected]

2 COLLAGE MU}IKA Il-{add, 26 ta’ Mejju, 2013 Gianluca jer;a’ jpo;;i lil Malta mal-aqwa g[axra minn Noel D’Anastas – [email protected] Issa li Tomorrow hi biss allegat serq ta’ voti lir-Russja storja tal-biera[, ]gur li l- avventura ta’ Gianluca minn dak li ori;inarjament Bezzina fil-Eurovision kellu jing[ata mill- f’Malmö se tibqa’ mmarkata Azerbaijan, ex Repubblika b’ittri kbar fid-djarju ta’ [ajtu. Sovjetika, wara li l-operaturi U bir-ra;un! tat-telefonija /ellulari “A doctor and part-time irri]ultalhom li 10 punti singer”, kif iddiskrivietu t- kellhom imorru g[ar-Russja, tabloid Ingli]a Daily Mirror i]da finalment ma [adu xejn fejn fl-anali]i tal-kanzunetti ming[and l-Azerbaijan. Ir- ftit jiem qabel kienet tatu Russja min-na[a tag[ha tat il- rankings g[olja, ir-ri]ultat massimu lill-Azerbaijan. miksub fit-tmien post Fit-tieni semifinali li fiha ikkonferma dan. Konna ilna Malta [adet sehem, mill-2005 ma nsibu postna ikklassifikajna fir-raba’ post mal-ewwel g[axra. F’dik is- b’118-il punt wara l- sena, Chiara kienet Azerbaijan li ;ab 139 punt, il- klassifikata fit-tieni post. Gre/ja 121 punt, u n-Norve;ja Jiem qabel ittella’ s-siparju, b’120 punt. G[all-kronaka, fir-Renju Unit, Fr Alexander Malta [adet 12-il punt mill- Lucie-Smith fil-Christian Azerbaijan, il-Ma/edonja u n- Herald kien wassal messa;; Norve;ja, 10 punti minn San biex g[all-jum tal-Pentekoste, Marino filwaqt li l-Bulgarija u jitolbu wkoll g[all-kanzunetta Spanja ma tawna xejn. -

Artistic Development – Accessibility Annual Report 2017

Opening Doors Association Inclusivity – Artistic Development – Accessibility Annual Report 2017 1. Introduction The Opening Doors Association continued to develop and flourish during 2017, its ninth year, and went through some exciting changes both to its funding structures and to the ways in which it manages and organizes its artistic programmes. Opening Doors, as a voluntary organisation, continues to use the Malta Centre for Voluntary Services at 181, Melita St., Valletta as its administrative base, where we are able to hold our Board meetings, but we have this year also signed a collaboration agreement with Teatru Salesjan, which affords us such support as office and meeting space, and a performance venue. At the start of the year, the following individuals were members of the board: Prof Jo Butterworth (chair), Brian Gauci (Treasurer), Sandra Mifsud (Artistic Director) Sara Polidano (vice-chair), Charlotte Stafrace, Justin Spiteri and Patrick Wirth. Group leaders were Rachel Calleja (Dance Group), Andrea Grancini (Theatre Group) and Luke Baldacchino (Music Group). Assistants during 2017 included Ilona Baldacchino, Jacob Piccinino, Mariele Zammit, Estelle Farrugia, Benji Cachia, Marie-Elena Farrugia, Martina Buhagiar and Dorienne Catania. Our two Patrons, Janatha Stubbs and Lou Ghirlando have continued to support the organisation. The Annual General Meeting (AGM) was held on the 29th March 2017 at Aġenzija Żgħażagħ St Joseph High Road St Venera SVR 1012. Dr Anne-Marie Callus from the University of Malta Department of Disability Studies, and Andrea Waltzing (nurse with experience of disability) were both nominated and voted in as new Board Members. A number of our members, parents, supporters and collaborators attended, including Giuliana Barbaro Sant, who ran our Crowdfunding Project with support from ZAAR, and singer Gianluca Bezzina who acted as the ambassador for the initiative. -

Neuroimaging Studies on Familiarity of Music in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Neuroimaging Studies on Familiarity of Music in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder by Carina Patricia De Barros Freitas A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Degree of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Carina Patricia De Barros Freitas 2020 Neuroimaging Studies on Familiarity of Music in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Carina Patricia De Barros Freitas Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto 2020 Abstract The field of music neuroscience allows us to use music to investigate human cognition in vivo. Examining how brain processes familiar and unfamiliar music can elucidate underlying neural mechanisms of several cognitive processes. To date, familiarity in music listening and its neural correlates in typical adults have been investigated using a variety of neuroimaging techniques, yet the results are inconsistent. In addition, these correlates and respective functional connectivity related to music familiarity in typically developing (TD) children and children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are unknown. The present work consists of two studies. The first one reviews and qualitatively synthesizes relevant literature on the neural correlates of music familiarity, in healthy adult populations, using different neuroimaging methods. Then it estimates the brain areas most active when listening to familiar and unfamiliar musical excerpts using a coordinate-based meta-analyses technique of neuroimaging data. We established that motor brain structures were consistently active during familiar music listening. The activation of these motor-related areas could reflect audio-motor synchronization to elements of the music, such as rhythm and melody, so that one can tap, dance and “covert” sing along with a known song. -

Notes and Links on Coverage of the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest from ESC Insight

ESC Insight - www.escinsight.com Notes and Links on coverage of the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest from ESC Insight Compiled by Ewan Spence, Thursday May 23rd, 2013. Introduction ESC Insight is an independent website that covers the world of the Eurovision, including this year's Eurovision Song Contest. Set up in 2010 to act as a new home for BAFTA nominated podcaster Ewan Spence and the two year old “Unofficial Eurovision Podcast”, it promised to deliver in-depth content, analysis, commentary, and knowledgeable articles around the Contest. The approach can be linked to a weekly periodical, contrasting it with daily news sites such as EscXtra. For the 2013 Contest, ESC Insight's core team of journalists remained intact from the 2012 season (Ewan Spence, Sharleen Wright, Samantha Ross, and Steven Newby), and our pool of contributing writers expanded (including John Egan, Monty Moncrieff, John Kennedy O'Connor, Dr Paul Jordan, Roy Delaney, and others). Following on from 2012, our 'long format' video show from Malmo focused on the meet- and-greet interviews from the first week of rehearsals, allowing us to interview every on- stage performer for Eurovision 2013. This was augmented by more traditional long-form interviews, and the return of Terry Vision, our puppet based former commentator forced out of retirement to cover the Contest. Operated by Ewan Spence, this customised Henson Muppet had his own popular series of light-hearted interviews each running between three and five minutes long. We had two additions to our regular coverage this year. The first was our mobile app. 'ESC Commentary' was a joint app with EscXtra, and developed by The Lab, an offshoot of O2 Telefonica is an innovation team that test new ideas & concepts fast, in an open environment. -

SBS Eurovision Songbook

ALBANIA Semi Final 2 / Saturday 14 May 7:30pm SBS Australia Artist: Eneda Tarifa Song: Fairytale This tale of love, larger than dreams, it may take a lifetime, To understand what it means. Many the tears, cos all the craziness and rage, Tale of love, the massage is Love can bring change. Cos it’s you...only you you I feel, And I ...oh I I know in my soul this it’s real REF And that’s why I love you..oh I Yes I love you u..u.. And I’d fight for you give my life for you my heart But comes a day when it’s not enough and what you have the time is up but it’s hard to turn a new page In the tale, sweet tale of love you will find the peace of heart that you crave Share your party pics #SBSEurovision sbs.com.au/eurovision ARMENIA Semi Final 1 / Friday 13 May 7:30pm SBS Australia Artist: Iveta Mukuchyan Song: LoveWave Hey it’s me. It’s taking over me. Look, I know it might sound strange but suddenly Instrumental I’m not the same I used to be. It’s taking, it’s taking over me. It’s like I’ve stepped out of space and time and come alive… Guess this is what it’s all about Chorus cause… You (oh like a lovewave) Shook my life like an earthquake now 1. ...when it touched me the world went silent, I’m waking up, Calm before the storm reaches me. -

Ira Losco 7Th Wonder Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ira Losco 7th Wonder mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: 7th Wonder Country: Germany Released: 2002 Style: Europop, Indie Pop MP3 version RAR size: 1764 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1796 mb WMA version RAR size: 1310 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 990 Other Formats: MP1 APE VOX MIDI AAC ADX TTA Tracklist Hide Credits 1 7th Wonder (Radio Mix) 2:58 7th Wonder (Club Mix) 2 3:07 Remix – Michael & Carsten 3 One Step Away 3:01 4 7th Wonder (Instrumental) 2:58 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – CAP-Sounds Copyright (c) – Musictales Licensed From – CAP-Sounds Distributed By – Koch Music Published By – CAP-Sounds Published By – Buddle Music, Norway Published By – Gothic Musikverlag Recorded At – CAP-Sounds Mixed At – CAP-Sounds Pressed By – Panteon Credits Backing Vocals – Chantal Hartmann Co-producer – Jürgen Blömke Cover, Design – Rate Guitar – Klaus Schloßer* Lyrics By – Gerard James Borg (tracks: 1, 2, 4), Philip Vella (tracks: 3) Music By – Philip Vella (tracks: 1, 2, 4), Ray Agius (tracks: 3) Other [Styling] – Nico Photography By – Christian Sauter Producer – Manfred Holz Programmed By [Add. Programming] – Philip Vella Recorded By, Mixed By – Frank Motnik Notes (C) 2002 MusicTales (P) 2002 Cap-Sounds Made in EU. Comes in j-card jewel case. On front cover: Eurovision Song Contest 2002 - Malta's Entry Note: Track 1 was the Maltese entry at the 2002 Eurovision Song Contest. Track 3 was an entry at the 2002 Maltese National Final (placed 3rd). Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4 260010 750166 Label Code: LC 11391 Matrix