The Nemedian Chroniclers #18 [SS15]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7322/the-nemedian-chroniclers-22-ws16-27322.webp)

The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]

REHeapa Winter Solstice 2016 By Lee A. Breakiron A WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON Few fiction authors are as a widely published internationally as Robert E. Howard (e.g., in Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Yugoslavian). As former REHupan Vern Clark states: Robert E. Howard has long been one of America’s stalwarts of Fantasy Fiction overseas, with extensive translations of his fiction & poetry, and an ever mushrooming distribution via foreign graphic story markets dating back to the original REH paperback boom of the late 1960’s. This steadily increasing presence has followed the growing stylistic and market influence of American fantasy abroad dating from the initial translations of H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham House collections in Spain, France, and Germany. The growth of the HPL cult abroad has boded well for other American exports of the Weird Tales school, and with the exception of the Lovecraft Mythos, the fantasy fiction of REH has proved the most popular, becoming an international literary phenomenon with translations and critical publications in Spain, Germany, France, Greece, Poland, Japan, and elsewhere. [1] All this shows how appealing REH’s exciting fantasy is across cultures, despite inevitable losses in stylistic impact through translations. Even so, there is sometimes enough enthusiasm among readers to generate fandom activities and publications. We have already covered those in France. [2] Now let’s take a look at some other countries. GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND SWITZERLAND The first Howard stories published in German were in the fanzines Pioneer #25 and Lands of Wonder ‒ Pioneer #26 (Austratopia, Vienna) in 1968 and Pioneer of Wonder #28 (Follow, Passau, Germany) in 1969. -

Australian SF News 28

NUMBER 28 registered by AUSTRALIA post #vbg2791 95C Volume 4 Number 2 March 1982 COW & counts PUBLISH 3 H£W ttOVttS CORY § COLLINS have published three new novels in their VOID series. RYN by Jack Wodhams, LANCES OF NENGESDUL by Keith Taylor and SAPPHIRE IN THIS ISSUE: ROAD by Wynne Whiteford. The recommended retail price on each is $4.95 Distribution is again a dilemna for them and a^ter problems with some DITMAR AND NEBULA AWARD NOMINATIONS, FRANK HERBERT of the larger paperback distributors, it seems likely that these titles TO WRITE FIFTH DUNE BOOK, ROBERT SILVERBERG TO DO will be handled by ALLBOOKS. Carey Handfield has just opened an office in Melbourne for ALLBOOKS and will of course be handling all their THIRD MAJIPOOR BOOK, "FRIDAY" - A NEW ROBERT agencies along with NORSTRILIA PRESS publications. HEINLEIN NOVEL DUE OUT IN JUNE, AN APPRECIATION OF TSCHA1CON GOH JACK VANCE BY A.BERTRAM CHANDLER, GEORGE TURNER INTERVIEWED, Philip K. Dick Dies BUG JACK BARRON TO BE FILMED, PLUS MORE NEWS, REVIEWS, LISTS AND LETTERS. February 18th; he developed pneumonia and a collapsed lung, and had a second stroke on February 24th, which put him into a A. BERTRAM CHANDLER deep coma and he was placed on a respir COMPLETES NEW NOVEL ator. There was no brain activity and doctors finally turned off the life A.BERTRAM CHANDLER has completed his support system. alternative Australian history novel, titled KELLY COUNTRY. It is in the hands He had a tremendous influence on the sf of his agents and publishers. GRIMES field, with a cult following in and out of AND THE ODD GODS is a short sold to sf fandom, but with the making of the Cory and Collins and IASFM in the U.S.A. -

Searchers After Horror Understanding H

Mats Nyholm Mats Nyholm Searchers After Horror Understanding H. P. Lovecraft and His Fiction // Searchers After Horror Horror After Searchers // 2021 9 789517 659864 ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 Åbo Akademi University Press Tavastgatan 13, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tel. +358 (0)2 215 4793 E-mail: [email protected] Sales and distribution: Åbo Akademi University Library Domkyrkogatan 2–4, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tel. +358 (0)2 -215 4190 E-mail: [email protected] SEARCHERS AFTER HORROR Searchers After Horror Understanding H. P. Lovecraft and His Fiction Mats Nyholm Åbo Akademis förlag | Åbo Akademi University Press Åbo, Finland, 2021 CIP Cataloguing in Publication Nyholm, Mats. Searchers after horror : understanding H. P. Lovecraft and his fiction / Mats Nyholm. - Åbo : Åbo Akademi University Press, 2021. Diss.: Åbo Akademi University. ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 ISBN 978-951-765-987-1 (digital) Painosalama Oy Åbo 2021 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to investigate the life and work of H. P. Lovecraft in an attempt to understand his work by viewing it through the filter of his life. The approach is thus historical-biographical in nature, based in historical context and drawing on the entirety of Lovecraft’s non-fiction production in addition to his weird fiction, with the aim being to suggest some correctives to certain prevailing critical views on Lovecraft. These views include the “cosmic school” led by Joshi, the “racist school” inaugurated by Houellebecq, and the “pulp school” that tends to be dismissive of Lovecraft’s work on stylistic grounds, these being the most prevalent depictions of Lovecraft currently. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

The Incredible, Once-In-A-Lifetime Munsey/Popular Publications Auction – Part 2!

The Incredible, Once-in-a-Lifetime Munsey/Popular Publications Auction – Part 2! As part of the Windy City Pulp and Paperback Convention’s Saturday night auction (beginning at approximately 8:00 p.m., following the Guest of Honor presentation), we will be presenting more material from the Munsey and Popular Publications archives. These lots will be mixed-in with the other lots during the auction. Please note that the listing below is subject to change and does not necessarily represent the order in which items will be auctioned. While we have endeavored to describe these lots carefully, bidders should personally examine the lots they’re interested in and raise any questions prior to the auction; the convention is not responsible for errors in descriptions. Purchase of any of these items at auction does not transfer copyright permissions or grant reprint permissions. When carbon letters are mentioned in connection with lots containing author correspondence, these are usually carbon copies of letters coming from various editors at Munsey or Popular Publications, replying to the author. * * * * * 1. REX STOUT - Munsey check endorsed by Stout for his novel, The Great Legend, from 1914. 2. JAMES FRANCIS DWYER - Munsey check (and copyright notice also) both endorsed by Dwyer for his novel, The White Waterfall, from 1912. 3. MODEST STEIN - Munsey check endorsed by Stein for his cover painting for The Radio Planet from 1926. 4. RAY CUMMINGS - Munsey check endorsed by Cummings for his novel, Tama of the Flying Virgins from 1930. 5. CHARLES WILLIAMS - Munsey check endorsed by Williams for his cover painting for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Girl from Farris’s from 1916. -

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs

I The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs: Lost Races and Racism in American Popular Culture James R. Nesteby Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy August 1978 Approved: © 1978 JAMES RONALD NESTEBY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ¡ ¡ in Abstract The Tarzan series of Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950), beginning with the All-Story serialization in 1912 of Tarzan of the Apes (1914 book), reveals deepseated racism in the popular imagination of early twentieth-century American culture. The fictional fantasies of lost races like that ruled by La of Opar (or Atlantis) are interwoven with the realities of racism, particularly toward Afro-Americans and black Africans. In analyzing popular culture, Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1932) and John G. Cawelti's Adventure, Mystery, and Romance (1976) are utilized for their indexing and formula concepts. The groundwork for examining explanations of American culture which occur in Burroughs' science fantasies about Tarzan is provided by Ray R. Browne, publisher of The Journal of Popular Culture and The Journal of American Culture, and by Gene Wise, author of American Historical Explanations (1973). The lost race tradition and its relationship to racism in American popular fiction is explored through the inner earth motif popularized by John Cleves Symmes' Symzonla: A Voyage of Discovery (1820) and Edgar Allan Poe's The narrative of A. Gordon Pym (1838); Burroughs frequently uses the motif in his perennially popular romances of adventure which have made Tarzan of the Apes (Lord Greystoke) an ubiquitous feature of American culture. -

Principles of Plant Taxonomy, V.*

THE OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE VOL. XXVIII MARCH, 1928 No. 2 PRINCIPLES OF PLANT TAXONOMY, V.* JOHN H. SCHAFFNER, Ohio State University. After studying the taxonomy of plants for twenty-five years the very remarkable fact became evident that there is no general correspondence of the taxonomic system with the environment, but as the great paleontologist, Williams, said in 1895: "environmental conditions are but the medium through which organic evolution has been determinately ploughing its way." Of course, the very fact that there is a system of phylogenetic relationships of classes, orders, families, and genera and that these commonly have no general correspondence to environment shows that, in classifying the plant material, we must discard all notions of teleological, utilitarian, and selective factors as causative agents of evolution. The general progressive movement has been carried on along quite definite lines. The broader and more fundamental changes appeared first and are practically constant, and on top of these, .potentialities or properties of smaller and smaller value have been introduced, until at the end new factors of little general importance alone are evolved. These small potentialities are commonly much less stable than the more fundamental ones and thus great variability in subordinate characters is often present in the highest groups. We must then think of the highest groups as being full of hereditary potentialities while the lower groups have comparatively few. As stated above, there is a profound non-correspondence of the .taxonomic system and the various orthogenetic series with the environment. The system of plants, from the taxonomic point of view, is non-utilitarian. -

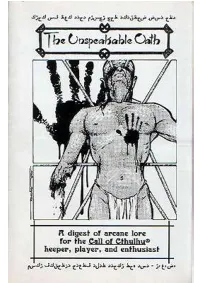

The Unspeakable Oath Issues 1 & 2 Page 1

The Unspeakable Oath issues 1 & 2 Page 1 Introduction to The Annotated Unspeakable Oath ©1993 John Tynes This is a series of freely-distributable text files that presents the textual contents of early issues of THE UNSPEAKABLE OATH, the world’s premiere digest for Chaosium’s CALL OF CTHULHU ™ role-playing game. Each file contains the nearly-complete text from a given issue. Anything missing is described briefly with the file, and is missing either due to copyright problems or because the information has been or will be reprinted in a commercial product. Everything in this file is copyrighted by the original authors, and each section carries that copyright. This file may be freely distributed provided that no money is charged whatsoever for its distribution. This file may only be distributed if it is intact, whole, and unchanged. All copyright notices must be retained. Modified versions may not be distributed — the contents belong to the creators, so please respect their work. Abusing my position as editor and instigator of the magazine and this project, I have taken the liberty of adding comments to some of the contents where I thought I had something interesting or historically worth preserving to say. Yeah, right! – John Tynes, editor-in-chief of Pagan Publishing The Unspeakable Oath issues 1 & 2 Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction to The Annotated Unspeakable Oath...................................................................................2 Introduction to TUO 1.........................................................................................................................4 -

Alternate Artifact and Conan Bonus Card

Your Kickstarter edition of Adventures in Hyboria includes extra components, not included in the regular retail edition of the expansion: — 3 alternate Artifact cards — 3 Artifact tokens — 1 alternate Conan Bonus card — 8 Conan’s Chronicle cards — 16 Conquest cards — 6 Hyborian God cards — 4 sets of Hyborian God tokens — 4 Sorcery cards In this rulebook, you will nd the necessary rules to add these components to your Age of Conan games. All components are optional, and they can be used together or separately. ALTERNATE ARTIFACT AND CONAN BONUS CARD 7KH6ZRUGRI $WODQWLV ,NMRSDQR 6GDMXNT@QDHMUNKUDCHM@ LHKHS@QXBNMSDRS XNTL@XOK@X SVNRSQ@SDFXB@QCR@MC@OOKXANSG DEEDBSR AOC0002KS—EXTRA CARDS 1/4 Artifact cards Artifact tokens (Front and Back) ere are two ways to use alternate artifacts and bonus card: — At the start of the game, players may mutually agree which of the two versions of each artifact (and Conan bonus) to use for this game. — Both versions are used. Whenever a player receives an artifact, he may decide which of the two versions to use. Also included in this expansion are three artifact die-cut tokens. You may use these tokens to show more visibly which player holds a speci c artifact. 1 CONAN’S CHRONICLE CARDS &RQDQWKH %$5%$5,$1 #Q@VSVN@CUDMSTQDSNJDMR *DDONMD @MCSQ@CDSGD NSGDQHLLDCH@SDKXENQFNKC NQRNQBDQX 8NTL@XLNUD "NM@M@MCOK@BDNMD Q@HCDQSNJDM AOC0002KS—CHRONICLE CARDS 1/8 Chronicle card (Front and Back) e deck of 8 chronicle cards is used to represent and indicate various moments in Conan’s life. Only one chronicle card is in play at any given moment. -

By Lee A. Breakiron a CIMMERIAN WORTHY of the NAME, PART

REHEAPA Vernal Equinox 2014 By Lee A. Breakiron A CIMMERIAN WORTHY OF THE NAME, PART THREE During his crusade to revitalize Robert E. Howard fanzines with his The Cimmerian, Leo Grin not only initiated a blog, as we saw last time, but also started publishing a new chapbook series called The Cimmerian Library. They were in the same format as the TC journal issues, but had reddish copper covers in a run of 100 copies for $15.00 each. He issued four titles (“volumes”): REHupan Rob Roehm’s An Index to Cromlech and The Dark Man (2005), REHupan Chris Gruber’s “Them’s Fightin’ Words”: Robert E. Howard on Boxing (2006) citing all of Howard’s quotations on the manly sport from his correspondence, with an introduction and index; John D. Haefele’s A Bibliography of Books and Articles Written by August W. Derleth Concerning Derleth and the Weird Tale and Arkham House Publishing (2006) with one “Addenda” [sic] (2008); and Don Herron’s “Yours for Faster Hippos”: Thirty Years of “Conan vs. Conantics” (2007) containing his pivotal critique of REH pasticheurs, especially L. Sprague de Camp, as well as some personal commentary on it and on Bran Mak Morn, Karl Edward Wagner, and Bruce Lee. And to properly celebrate the Centennial of Howard’s birth, as well as the 70th anniversary of his death, the 60th year since the publication of the landmark Arkham House volume Skull-Face and Others, and the 20th year since the first pilgrimage of REHupans to Cross Plains, Texas, Grin wondered what he could “do to make it extra special, to truly convey the respect and admiration I have for the man and his writings?” (Vol. -

Cthulhu Through the Ages Is Copyright © 2014 by Chaosium Inc

AUTHORS Mike Mason, Pedro Ziviani, John French, and Chad Bowser EDITING Mike Mason and Dustin Wright CARTOGRAPHY Stephanie McAlea INVESTIGATOR SHEETS Dean Engelhardt LAYOUT Nicholas Nacario COVER ILLUSTRATION Paul Carrick INTERIOR ILLUSTRATIONS Steven Gilberts, Sam Lamont, Florian Stitz, Paul Carrick, Goomi, Raymond Bayless, Nicholas Nacario. Some images were taken from Wikicommons and are in the public domain. THANKS TO Alan Bligh, John French, Matt Anderson, Penda Tomlin- son, and Dustin Wright. A special thanks to all of our 7th edition kickstarter backers who helped make this book possible. This supplement is best used with the roleplaying game CALL OF CTHULHU, available separately. Find more Chaosium Inc. products at www.chaosium.com Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 Cthulhu Through the Ages is copyright © 2014 by Chaosium Inc. All rights reserved. The names of public personalities may be referred to, but any resemblance of a scenario character to persons liv- ing or dead is strictly coincidental. Except in this publication and associated advertising, all illustrations for CTHULHU THROUGH THE AGES remain the property of the artists, who otherwise reserve all rights. This adventure pack is best used with the roleplaying game CALL OF CTHULHU, available separately. Find more Chaosium Inc. products at www.chaosium.com Item # 23146 ISBN10: 1568824386 ISBN13: 978-1568824383 Printed in USA Contents Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������ 5 Cthulhu Invictus ������������������������������������������������������������������