Bolivia! Welcome to Bolivia!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

35603 EXPRESS REV.Indd

BolivianExpress Free Distribution Magazine Roots # 30 Directors: Amaru Villanueva Rance, Jack Kinsella, Xenia Elsaesser, Ivan Rodriguez Petkovic, Sharoll Fernandez. Editorial Team: Amaru Villanueva Rance, Matthew Grace,Juan Victor Fajardo. Web and Legal: Jack Kinsella. Printing and Advertising Manager: Ivan Rodriguez Petkovic. Social and Cultural Coordinator: Sharoll Fernandez. General Coordinator: Wilmer Machaca. Research Assistant: Wilmer Machaca. Domestic Coordinator: Virginia Tito Gutierrez. Design: Michael Dunn Caceres. Journalists: Ryle Lagonsin, Alexandra Meleán, Wilmer Machaca, Maricielo Solis, Danielle Carson, Caterina Stahl Our Cover: The BX Crew Marketing: Xenia Elsaesser The Bolivian Express Would Like To Thank: Simon Yampara, Pedro Portugal, Mirna Fernández, Paola Majía, Alejandra Soliz, Eli Blass, Hermana Jhaana, Joaquín Leoni Advertise With Us: [email protected]. Address: Calle Prolongación Armaza # 2957, Sopocachi, La Paz.. Phone: 78862061- 70503533 - 70672031 Contact: [email protected] Rooted in La Paz – Bolivia, July 2013 :BolivianExpress @Bolivianexpress www.bolivianexpress.org History a tierra es de quien la trabaja’—’Th e land belongs to those who work it’, proclaimed the Zapatistas at the turn of the 20th Century, as Emiliano Zapata spearheaded the historical movement which we now remember as the Mexican Revolution. ‘L 40 years later, this same slogan propelled Bolivian campesinos to demand broad socioeconomic changes in a country which hadn’t yet granted them basic citizenship rights, let alone recognised they made up over 70% of the country’s population. A broad-sweeping Agrarian Reform followed in 1953, giving these peasants unprecedented ownership and control over the land they worked on. Th e Bolivian Revolution of 1952 also enfranchised women and those considered illiterate (a convenient proxy for campes- inos), causing a fi vefold increase in the number of people eligible to vote. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

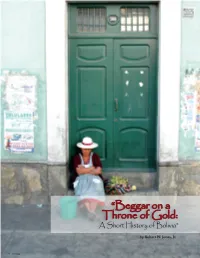

“Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia” by Robert W. Jones, Jr. 6 Veritas is a land of sharp physical and social contrasts. Although blessed with Benormousolivia mineral wealth Bolivia was (and is) one of the poorest nations of Latin America and has been described as a “Beggar on a Throne of Gold.” 1 This article presents a short description of Bolivia as it appeared in 1967 when Che Guevara prepared to export revolution to the center of South America. In Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia was ripe for revolution with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population. This article covers the geography, history, and politics of Bolivia. Geography and Demographics Bolivia’s terrain and people are extremely diverse. Since geography is a primary factor in the distribution of the population, these two aspects of Bolivia will be discussed together. In the 1960s Bolivian society was predominantly rural and Indian unlike the rest of South America. The Indians, primarily Quechua or Aymara, made up between fifty to seventy percent of the population. The three major Indian dialects are Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní. The remainder of the population were whites and mixed races (called “mestizos”). It is difficult to get an accurate census because The varied geographic regions of Bolivia make it one of the Indians have always been transitory and there are the most climatically diverse countries in South America. cultural sensitivities. Race determines social status in Map by D. Telles. Bolivian society. A mestizo may claim to be white to gain vegetation grows sparser towards the south, where social status, just as an economically successful Indian the terrain is rocky with dry red clay. -

Iv BOLIVIA the Top of the World

iv BOLIVIA The top of the world Bolivia takes the breath away - with its beauty, its geographic and cultural diversity, and its lack of oxygen. From the air, the city of La Paz is first glimpsed between two snowy Andean mountain ranges on either side of a plain; the spread of the joined-up cities of El Alto and La Paz, cradled in a huge canyon, is an unforgettable sight. For passengers landing at the airport, the thinness of the air induces a mixture of dizziness and euphoria. The city's altitude affects newcomers in strange ways, from a mild headache to an inability to get up from bed; everybody, however, finds walking up stairs a serious challenge. The city's airport, in the heart of El Alto (literally 'the high place'), stands at 4000 metres, not far off the height of the highest peak in Europe, Mont Blanc. The peaks towering in the distance are mostly higher than 5000m, and some exceed 6000m in their eternally white glory. Slicing north-south across Bolivia is a series of climatic zones which range from tropical lowlands to tundra and eternal snows. These ecological niches were exploited for thousands of years, until the Spanish invasion in the early sixteenth century, by indigenous communities whose social structure still prevails in a few ethnic groups today: a single community, linked by marriage and customs, might live in two or more separate climes, often several days' journey away from each other on foot, one in the arid high plateau, the other in a temperate valley. -

La Morenada: Una Mirada Desde La Perspectiva De Género

La Morenada: una mirada desde la perspectiva de género Elizabeth del Rosario Rojas1 Universidad Nacional de Luján Argentina Introducción: La Morenada es una danza propia del área andina suramericana y se caracteriza por el uso de trajes coloridos y pasos rítmicos que al son de la música dan cuenta de la vida cotidiana. Actualmente es legado cultural de las mujeres bolivianas que habitan en Buenos Aires. El presente trabajo centra su análisis en un grupo de mujeres bolivianas que bailan Morenada en Lomas de Zamora, específicamente en el Barrio 6 de agosto. El objetivo es visibilizar La Morenada y responder a la pregunta, ¿cómo está inscripta en la memoria colectiva de las Mujeres bolivianas? Asimismo, interesa ofrecer una mirada de la danza como una práctica diaria, mezclada con la mística de agradecimiento y ofrenda a diversas vírgenes, según la petición que realizan y cómo se despliega de generación y en generación, al decir de ellas mismas, un pedacito de lo andino se traslada a esta tierra pampeana. Palabra Clave Género: es una categoría relacional, producto de la construcción social de jerarquización que se asienta en el patriarcado que toma como base la diferencia de sexos: femenino, masculino. Donde el patriarcado hace que lo masculino nomine, mande y sea quien organice esta jerarquización donde lo femenino queda subordinado en el sistema social (Amoros, 1985) Cultura: se entenderá por cultura todo aquello que se desarrolle como popular, que hace a lo simbólico material e inmaterial (creencias, saberes; prácticas; etc.) que se transmite de generación en generación, donde la reproducción se estructura conforme un orden, que es organizado desde contextos sociopolíticos, dentro de procesos históricos, que ayuda a comprender los roles de las diversas identidades sexuales (Scott, 1994) I. -

Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War Roniger, Luis; Senkman, Leonardo

www.ssoar.info Fuel for Conspiracy: Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War Roniger, Luis; Senkman, Leonardo Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Roniger, L., & Senkman, L. (2019). Fuel for Conspiracy: Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 11(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X19843008 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Journal of Politics in j Latin America Research Article Journal of Politics in Latin America 2019, Vol. 11(1) 3–22 Fuel for Conspiracy: ª The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Suspected Imperialist sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1866802X19843008 Plots and the Chaco War journals.sagepub.com/home/pla Luis Roniger1 and Leonardo Senkman2 Abstract Conspiracy discourse interprets the world as the object of sinister machinations, rife with opaque plots and covert actors. With this frame, the war between Bolivia and Paraguay over the Northern Chaco region (1932–1935) emerges as a paradigmatic conflict that many in the Americas interpreted as resulting from the conspiracy man- oeuvres of foreign oil interests to grab land supposedly rich in oil. At the heart of such interpretation, projected by those critical of the fratricidal war, were partial and extrapolated facts, which sidelined the weight of long-term disputes between these South American countries traumatised by previous international wars resulting in humiliating defeats and territorial losses, and thus prone to welcome warfare to bolster national pride and overcome the memory of past debacles. -

Performing Blackness in the Danza De Caporales

Roper, Danielle. 2019. Blackface at the Andean Fiesta: Performing Blackness in the Danza de Caporales. Latin American Research Review 54(2), pp. 381–397. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.300 OTHER ARTS AND HUMANITIES Blackface at the Andean Fiesta: Performing Blackness in the Danza de Caporales Danielle Roper University of Chicago, US [email protected] This study assesses the deployment of blackface in a performance of the Danza de Caporales at La Fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria in Puno, Peru, by the performance troupe Sambos Illimani con Sentimiento y Devoción. Since blackface is so widely associated with the nineteenth- century US blackface minstrel tradition, this article develops the concept of “hemispheric blackface” to expand common understandings of the form. It historicizes Sambos’ deployment of blackface within an Andean performance tradition known as the Tundique, and then traces the way multiple hemispheric performance traditions can converge in a single blackface act. It underscores the amorphous nature of blackface itself and critically assesses its role in producing anti-blackness in the performance. Este ensayo analiza el uso de “blackface” (literalmente, cara negra: término que designa el uso de maquillaje negro cubriendo un rostro de piel más pálida) en la Danza de Caporales puesta en escena por el grupo Sambos Illimani con Sentimiento y Devoción que tuvo lugar en la fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria en Puno, Perú. Ya que el “blackface” es frecuentemente asociado a una tradición estadounidense del siglo XIX, este artículo desarrolla el concepto de “hemispheric blackface” (cara-negra hemisférica) para dar cuenta de elementos comunes en este género escénico. -

Current Studies on South American Languages, [Indigenous Languages of Latin America (ILLA), Vol

This file is freely available for download at http://www.etnolinguistica.org/illa This book is freely available for download at http://www.etnolinguistica.org/illa References: Crevels, Mily, Simon van de Kerke, Sérgio Meira & Hein van der Voort (eds.). 2002. Current Studies on South American Languages, [Indigenous Languages of Latin America (ILLA), vol. 3], [CNWS publications, vol. 114], Leiden: Research School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies (CNWS), vi + 344 pp. (ISBN 90-5789-076-3) CURRENT STUDIES ON SOUTH AMERICAN LANGUAGES INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES OF LATIN AMERICA (ILLA) This series, entitled Indigenous Languages of Latin America, is a result of the collaboration between the CNWS research group of Amerindian Studies and the Spinoza research program Lexicon and Syntax, and it will function as an outlet for publications related to the research program. LENGUAS INDÍGENAS DE AMÉRICA LATINA (ILLA) La serie Lenguas Indígenas de América Latina es el resultado de la colabora- ción entre el equipo de investigación CNWS de estudios americanos y el programa de investigación Spinoza denominado Léxico y Sintaxis. Dicha serie tiene como objetivo publicar los trabajos que se lleven a cabo dentro de ambos programas de investigación. Board of advisors / Consejo asesor: Willem Adelaar (Universiteit Leiden) Eithne Carlin (Universiteit Leiden) Pieter Muysken (Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen) Leo Wetzels (Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam) Series editors / Editores de la serie: Mily Crevels (Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen) Simon van de Kerke (Universiteit -

La Virgen De La Candelaria: Origen, Representación Y Fe En El Altiplano Peruano

LA VIRGEN DE LA CANDELARIA: ORIGEN, REPRESENTACIÓN Y FE EN EL ALTIPLANO PERUANO Arql. Neiser Ruben Jalca Espinoza Proyecto Qhapaq Ñan Al hablar del sentir religioso en nuestro país, es obligatorio hacer mención a la Virgen de la Candelaria, por su historia e importancia reflejada en una fuerte devoción imperante en toda el área altiplánica y fuera de ella; pues, durante su mundialmente conocida celebración en febrero, se aprecia la congregación de miles de espectadores provenientes de distintas provincias y países, entre curiosos, devotos y apreciadores del arte, quienes son espectadores, y en algunos casos participantes, del despliegue de horas y días colmados de celebraciones y danzas de gran diversidad. Origen del culto Tras la famosa festividad, surge la interrogante respecto al origen del despliegue multitudinario de fe hacia la Virgen de la Candelaria. Para resolverla, debemos remontarnos al año 1392 en Tenerife, España. Tenerife es la isla más grande del archipiélago de las Canarias, la cual era parada obligatoria en los viajes desde dicho país hacia América, por ello, su imagen fue inculcada en el territorio colonial. Según De Orellana (2015) la devoción en Perú se originó en el pueblo de Huancané, en Arcani, al norte de Puno. La imagen obtuvo un número cada vez mayor de seguidores, los cuales lograron que ésta fuera trasladada a la iglesia de San Juan de Puno, convirtiéndose en el Santuario de la Virgen de la Candelaria, quien obtuvo mayor aceptación y veneración que el mismo patrón San Juan. La devoción a esta virgen, en el altiplano, se desarrolla con intensidad desde la atribución de la protección de la villa de Puno en 1781, cercada por las fuerzas rebeldes de Túpac Catari, pues su imagen (traída el 2 de febrero de 1583 desde Cádiz o de Sevilla, España) fue sacada en procesión, lo que generó el repliegue de los guerreros al pensar que se trataba de fuerzas de apoyo para el ejército español allí guarecido. -

Las Danzas De Oruro En Buenos Aires: Tradición E Innovación En El Campo

Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales - Universidad Nacional de Jujuy ISSN: 0327-1471 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Argentina Gavazzo, Natalia Las danzas de oruro en buenos aires: Tradición e innovación en el campo cultural boliviano Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales - Universidad Nacional de Jujuy, núm. 31, octubre, 2006, pp. 79-105 Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Jujuy, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=18503105 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto CUADERNOS FHyCS-UNJu, Nro. 31:79-105, Año 2006 LAS DANZAS DE ORURO EN BUENOS AIRES: TRADICIÓN E INNOVACIÓN EN EL CAMPO CULTURAL BOLIVIANO (ORURO´S DANCES IN BUENOS AIRES: TRADITION AND INNOVATION INTO THE BOLIVIAN CULTURAL FIELD) Natalia GAVAZZO * RESUMEN El presente trabajo constituye un fragmento de una investigación realizada entre 1999 y 2002 sobre la migración boliviana en Buenos Aires. La misma describía las diferencias que se dan entre la práctica de las danzas del Carnaval de Oruro en esta ciudad, y particularmente la Diablada, y la que se da en Bolivia, para poner en evidencia las disputas que los cambios producido por el proceso migratorio conllevan en el plano de las relaciones sociales. Este trabajo analizará entonces los complejos procesos de selección, reactualización e invención de formas culturales bolivianas en Buenos Aires, particularmente de esas danzas, como parte de la dinámica de relaciones propia de un campo cultural, en el que la construcción de la autoridad y de poderes constituyen elementos centrales. -

CONSUMO, CULTURA E IDENTIDAD EN EL MUNDO GLOBALIZADO Estudios De Caso En Los Andes

CONSUMO, CULTURA E IDENTIDAD EN EL MUNDO GLOBALIZADO Estudios de caso en los Andes CONSUMO, CULTURA E IDENTIDAD EN EL MUNDO GLOBALIZADO Estudios de caso en los Andes LUDWIG HUBER IEP Instituto de Estudios Peruanos COLECCIÓN MÍNIMA, 50 Este libro es resultado del Programa de Investigaciones "Globalización, diversidad cultural y redefinición de identidades en los países andinos" que cuenta con el auspicio de la División de Humanidades de la Fundación Rockefeller. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, IEP Horacio Urteaga 694, Lima 11 Telf: [511] 332-6194/424-4856 Fax: 332-6173 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 9972-51-066-2 ISSN: 1019-4479 Impreso en el Perú la. edición, abril del 2002 1,000 ejemplares Hecho el depósito legal: 1501052002-1692 LUDWIG HUBER Consumo, cultura e identidad en el mundo globalizado: estudios de caso en los Andes.--Lima, IEP: 2002.--(Colección Mínima, 50) CAMBIO CULTURAL/ GLOBALIZACIÓN/ CIENCIAS SOCIALES/ IDENTIDAD/ PERÚ/ AYACUCHO/ HUAMANGA/ BOLIVIA W/05.01.01/M/50 Agradezco a la Fundación Rockefeller por la beca que hizo posible este estudio; a los estudiantes Villeón Tineo, Yovana Mendieta, Clay Quicaña, Lenin Castillo, Ángel Erasmo y Edgar Alberto Tucno, todos de la Universidad San Cristóbal de Huamanga, y a Brezhney Espinoza de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, por el apoyo en el trabajo de campo. LUDWIG HUBER es antropólogo, egresado de la Universidad Libre de Berlín. Actualmente es coordinador de investigaciones de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación, Sede Regional Ayacucho. CONTENIDO I. GLOBALIZACIÓN Y CULTURA 9 La globalización y sus desencantos 9 ¿Hacia una cultura global? 13 II. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO the Politics of Representing the Past in Bolivia a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfa

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Politics of Representing the Past in Bolivia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Edward Fabian Kennedy Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Grey Postero, Chair Professor Jeffrey Haydu Professor Steven Parish Professor David Pedersen Professor Leon Zamosc 2009 Copyright Edward Fabian Kennedy, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Edward Fabian Kennedy is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my mother, Maud Roberta Roehl Kennedy. iv EPIGRAPH “Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in anything simply because it is spoken and rumored by many. Do not believe in anything simply because it is found written in your religious books. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations. But after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit of one and all, then accept it -

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of Hist

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ABSTRACT Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Elizabeth Shesko 2012 Abstract This dissertation examines the trajectory of military conscription in Bolivia from Liberals’ imposition of this obligation after coming to power in 1899 to the eve of revolution in 1952. Conscription is an ideal fulcrum for understanding the changing balance between state and society because it was central to their relationship during this period. The lens of military service thus alters our understandings of methods of rule, practices of authority, and ideas about citizenship in and belonging to the Bolivian nation. In eliminating the possibility of purchasing replacements and exemptions for tribute-paying Indians, Liberals brought into the barracks both literate men who were formal citizens and the non-citizens who made up the vast majority of the population.