Yoruba Personal Naming System: Traditions, Patterns and Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cassava Farmers' Preferences for Varieties and Seed Dissemination

Cassava farmers’ preferences for varieties and seed dissemination system in Nigeria: Gender and regional perspectives Jeffrey Bentley, Adetunji Olanrewaju, Tessy Madu, Olamide Olaosebikan, Tahirou Abdoulaye, Tesfamichael Wossen, Victor Manyong, Peter Kulakow, Bamikole Ayedun, Makuachukwu Ojide, Gezahegn Girma, Ismail Rabbi, Godwin Asumugha, and Mark Tokula www.iita.org i ii Cassava farmers’ preferences for varieties and seed dissemination system in Nigeria: Gender and regional perspectives J. Bentley, A. Olanrewaju, T. Madu, O. Olaosebikan, T. Abdoulaye, T. Wossen, V. Manyong, P. Kulakow, B. Ayedun, M. Ojide, G. Girma, I. Rabbi, G. Asumugha, and M. Tokula International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan February 2017 IITA Monograph i Published by the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) Ibadan, Nigeria. 2017 IITA is a non-profit institution that generates agricultural innovations to meet Africa’s most pressing challenges of hunger, malnutrition, poverty, and natural resource degradation. Working with various partners across sub-Saharan Africa, we improve livelihoods, enhance food and nutrition security, increase employment, and preserve natural resource integrity. It is a member of the CGIAR System Organization, a global research partnership for a food secure future. International address: IITA, Grosvenor House, 125 High Street Croydon CR0 9XP, UK Headquarters: PMB 5320, Oyo Road Ibadan, Oyo State ISBN 978-978-8444-82-4 Correct citation: Bentley, J., A. Olanrewaju, T. Madu, O. Olaosebikan, T. Abdoulaye, T. Wossen, V. Manyong, P. Kulakow, B. Ayedun, M. Ojide, G. Girma, I. Rabbi, G. Asumugha, and M. Tokula. 2017. Cassava farmers’ preferences for varieties and seed dissemination system in Nigeria: Gender and regional perspectives. IITA Monograph, IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria. -

Purple Hibiscus

1 A GLOSSARY OF IGBO WORDS, NAMES AND PHRASES Taken from the text: Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Appendix A: Catholic Terms Appendix B: Pidgin English Compiled & Translated for the NW School by: Eze Anamelechi March 2009 A Abuja: Capital of Nigeria—Federal capital territory modeled after Washington, D.C. (p. 132) “Abumonye n'uwa, onyekambu n'uwa”: “Am I who in the world, who am I in this life?”‖ (p. 276) Adamu: Arabic/Islamic name for Adam, and thus very popular among Muslim Hausas of northern Nigeria. (p. 103) Ade Coker: Ade (ah-DEH) Yoruba male name meaning "crown" or "royal one." Lagosians are known to adopt foreign names (i.e. Coker) Agbogho: short for Agboghobia meaning young lady, maiden (p. 64) Agwonatumbe: "The snake that strikes the tortoise" (i.e. despite the shell/shield)—the name of a masquerade at Aro festival (p. 86) Aja: "sand" or the ritual of "appeasing an oracle" (p. 143) Akamu: Pap made from corn; like English custard made from corn starch; a common and standard accompaniment to Nigerian breakfasts (p. 41) Akara: Bean cake/Pea fritters made from fried ground black-eyed pea paste. A staple Nigerian veggie burger (p. 148) Aku na efe: Aku is flying (p. 218) Aku: Aku are winged termites most common during the rainy season when they swarm; also means "wealth." Akwam ozu: Funeral/grief ritual or send-off ceremonies for the dead. (p. 203) Amaka (f): Short form of female name Chiamaka meaning "God is beautiful" (p. 78) Amaka ka?: "Amaka say?" or guess? (p. -

African American Parent Groups As a Context for the Activation of Social Capital : a Case of Parent Empowerment Through Transformational Leadership Ajamu T

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2008 African American parent groups as a context for the activation of social capital : a case of parent empowerment through transformational leadership Ajamu T. Stewart Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, Ajamu T., "African American parent groups as a context for the activation of social capital : a case of parent empowerment through transformational leadership" (2008). Doctoral Dissertations. 232. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/232 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco AFRICAN AMERICAN PARENT GROUPS AS A CONTEXT FOR THE ACTIVATION OF SOCIAL CAPITAL: A CASE OF PARENT EMPOWERMENT THROUGH TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP A Dissertation Presented To The Faculty of the School of Education Organization and Leadership Department In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Ajamu T. Stewart San Francisco May, 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’d like to acknowledge my committee, Dr. Patricia Mitchell (my committee chair), Dr. Betty Taylor and Dr. Ellen Herda. Thanks for your patience and encouragement. Each of you contributed greatly to my experience at the University of San Francisco, and you will always be remembered. -

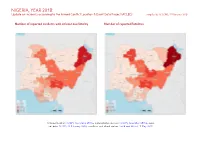

NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020

NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 22 February 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 705 566 2853 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 474 373 2470 Development of conflict incidents from 2009 to 2018 2 Protests 427 3 3 Riots 213 61 154 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 117 3 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 100 84 759 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 2036 1090 6243 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2009 to 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). 2 NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Analysis of Heavy Metals in Vegetables Sold in Ijebu-Igbo, Ijebu North Local Government, Ogun State, Nigeria

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 11, November-2015 130 ISSN 2229-5518 Analysis of Heavy Metals in Vegetables Sold in Ijebu-Igbo, Ijebu North Local Government, Ogun State, Nigeria *ABIMBOLA ‘WUNMI. A1, AKINDELE SHERIFAT. T2, JOKOTAGBA OLORUNTOBI. A2, AGBOLADE OLUFEMI .M1, AND SAM-WOBO SAMMY.O3 1Plant science and Applied Zoology Department, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State. 2Science Laboratory Technology Department, Abraham Adesanya Polytechnic, Ijebu-Igbo, Ogun State. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria Abstract - A preliminary market study was conducted to assess the level of certain heavy metal in selected vegetable sold in Obada market and Atikori market, harvested from three farm-lands located in Ayesan, Dagbolu and Osunbodepo in Ijebu North Local Area Government. The vegetables were bitter-leaf (Vernonia amygdalina), fluted pumpkin (Talfaria occidentalis), water-leaf (Talinum triangulare), and jute mallow (Corchorus olitorius). The samples were analysed for heavy metals (Cr, Mn, Ni, Co, Cu, Cd, Zn, Pb, and Fe) using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS, Perkin Elmer model 2130), in accordance with AOAC. The result obtained showed, Jute Mallow had highest value of Zinc with 111.23 and lowest value of Co with 3.50; fluted Pumpkin had highest value of Mn with 45.50 and lowest value in CO with 1.75; Water Leaf had Zn with highest value 186.75 and Cd has the lowest; Bitter Leaf had Zn with 90.50 and Cd with 1.50. Keywords - Farm, Heavy Metals, Site, spectrophotometer, Vegetables —————————— —————————— INTRODUCTION vegetables contamination with heavy metals Heavy metal contamination of vegetables cannot derives from factors such as the application of be under-estimated as these foodstuffs are fertilizers, sewage sludge or irrigation with important componentsIJSER of human diet. -

Decoding Encoded Yorùbá Nomenclature: an Exercise of National Research University Higher School of Economics Linguistic Competence and Performance

Dalamu, T.O. (2019). Decoding Encoded Yorùbá Nomenclature: An Exercise of National Research University Higher School of Economics Linguistic Competence and Performance. Journal of Language and Education, Journal of Language & Education Volume 5, Issue 1, 2019 5(1), 16-28. doi: 10.17323/2411-7390-2019-5-1-16-28 Decoding Encoded Yorùbá Nomenclature: An Exercise of Linguistic Competence and Performance Taofeek Olaiwola Dalamu Anchor University Lagos Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Taofeek Olaiwola Dalamu, Department of English & Literary Studies, Anchor University Lagos, Lagos, 1-4 Ayobo Road, Ipaja, Lagos, Nigeria. E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] The proficiency of Yorùbá users has influenced the formation of towns’ names, which this study investigated, revealing their haphazard formation processes. Ten towns of Yorùbá-land in Nigeria functioned as exploratory samples. Ellipsis, serving as the analytical instrument, elucidated the effectiveness of competence and performance, being operational in the clipping of statements to nominal lexemes. The study exhibited flexibility in the development of Yorùbá names, influenced by users’ needs. The historical facts of business, religion, hunting, war, and conquest supported the formations, without seemingly consistent linguistic principles. The study further revealed the deletion of linguistic components (Ilè̩ tó ń fè̩ = Ilé-Ifè̩ – a piece of land that expands), twists in pronunciations with a meaningless derivative (Ọjà kò tà – business is not picking up = Ọjó̩ta), manipulation of English words to Yorùbá (Bad agric = bà dá gìrì [Badagry]), and the production of novel lexemes-cum-meanings (Amúkokò – a person who catches a leopard = Amùkòkò – someone who smokes his pipe). -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu -

Integrated Geophysical Investigation of a Suspected Spring in Igbokoran, Ikare-Akoko, Southwestern Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Applied Geology and Geophysics (IOSR-JAGG) e-ISSN: 2321–0990, p-ISSN: 2321–0982.Volume 3, Issue 5 Ver. I (Sep. - Oct. 2015), PP 83-91 www.iosrjournals.org Integrated Geophysical Investigation of a Suspected Spring in Igbokoran, Ikare-Akoko, Southwestern Nigeria Onoja S.O1, Osifila A.J2, 1(Department of Physics, kogi State University Anyigba,Nigeria) 2(Department of Applied Geophysics, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria) Abstract: An integrated geophysical investigation involving self potential (SP), very low frequency electromagnetic (VLF-EM) and electrical resistivity methods (VES) were conducted around a suspected spring in Igbokoran, Ikare Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria in other to understand the nature of the spring as well as evaluate the feasibility of ground water development in the area. Three geophysical traverses of length 240m each were established in the study area in approximately E-W direction. VLF-EM measurements with station spacing of 10m was used as reconnaissance to delineate conductive zones between 70-160m along traverse 1, 80-170 m along traverse 2 and 60-180m along traverse 3.This was then followed by a total of six (6) VES stations along traverses 2 and 3 using the Schlumberger array with electrode spacing (AB/2) ranging from 1 to 150m. Three geoelectric layers (Top layer, weathered layer, and fresh basement) were delineated along all traverses and a suspected fractured basement along traverse three .The Self Potential (SP) measurements were carried out at 5m electrode separation employing the total fixed base array. SP profiles were generated which show anomalies with short negative amplitudes some of which coincides with the spring zone. -

The Use of Nigerian Pidgin in Media Adverts

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 4, No. 2; 2014 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Use of Nigerian Pidgin in Media Adverts Joseph Babasola Osoba1 1 Department of English, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria Correspondence: Joseph Babasola Osoba, Department of English, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: November 27, 2013 Accepted: February 1, 2014 Online Published: March 26, 2014 doi:10.5539/ijel.v4n2p26 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v4n2p26 Abstract The use of Nigerian Pidgin seems to have gained a wider currency since Nigeria’s independence in 1960. Among the educated and barely educated, the pidgin is used profusely in many spheres of life, especially in informal situations. In the mass media (television, radio, magazines and newspapers), schools, higher institutions of learning, government offices, etc., pidgin discourse abounds. In fact, despite the fact that it is not yet an official lingua franca in the country, it is a daily phenomenon in every day affair of an average Nigerian. The nature of Nigerian Pidgin, its easy mode of acquisition as well as the multilingual background of Nigerians may have been responsible for its present status and functions. In the light of the above, I am interested in how meaning is assigned to a piece of pidgin discourse, especially an advert in Nigerian Pidgin. Thus the goal of this paper is to establish how pidgin adverts communicate the intended meaning of their advertisers and how the audiences perceive them through an application of “Presupposition” and “Implicature” as conceptual or theoretical tools. -

Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson a Dissertation S

Mothers in the Family of Saints: Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paul Christopher Johnson, Chair Associate Professor Paulina Alberto Associate Professor Victoria Langland Associate Professor Gayle Rubin Jamie Lee Andreson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1305-1256 © Jamie Lee Andreson 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all the women of Candomblé, and to each person who facilitated my experiences in the terreiros. ii Acknowledgements Without a doubt, the most important people for the creation of this work are the women of Candomblé who have kept traditions alive in their communities for centuries. To them, I ask permission from my own lugar de fala (the place from which I speak). I am immensely grateful to every person who accepted me into religious spaces and homes, treated me with respect, offered me delicious food, good conversation, new ways of thinking and solidarity. My time at the Bate Folha Temple was particularly impactful as I became involved with the production of the documentary for their centennial celebrations in 2016. At the Bate Folha Temple I thank Dona Olga Conceição Cruz, the oldest living member of the family, Cícero Rodrigues Franco Lima, the current head priest, and my closest friend and colleague at the temple, Carla Nogueira. I am grateful to the Agência Experimental of FACOM (Department of Communications) at UFBA (the Federal University of Bahia), led by Professor Severino Beto, for including me in the documentary process. -

Socio-Economic Impacts of Settlers in Ado-Ekiti

International Journal of History and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) Volume 3, Issue 2, 2017, PP 19-26 ISSN 2454-7646 (Print) & ISSN 2454-7654 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-7654.0302002 www.arcjournals.org Socio-Economic Impacts of Settlers in Ado-Ekiti Adeyinka Theresa Ajayi (PhD)1, Oyewale, Peter Oluwaseun2 Department of History and International Studies, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State Nigeria Abstract: Migration and trade are two important factors that led to the commercial growth and development of Ado-Ekiti during pre-colonial, colonial and post colonial period. These twin processes were facilitated by efforts of other ethnic groups, most notably the Ebira among others, and other Yoruba groups. Sadly there is a paucity of detailed historical studies on the settlement pattern of settlers in Ado-Ekiti. It is in a bid to fill this gap that this paper analyses the settlement pattern of settlers in Ado-Ekiti. The paper also highlights the socio- economic and political activities of settlers, especially their contributions to the development of Ado-Ekiti. Data for this study were collected via oral interviews and written sources. The study highlights the contributions of settlers in Ado-Ekiti to the overall development of the host community 1. INTRODUCTION Ado-Ekiti, the capital of Ekiti state is one of the state in southwest Nigeria. the state was carved out from Ondo state in 1996, since then, the state has witness a tremendous changes in her economic advancement. The state has witness the infix of people from different places. Settlement patterns in intergroup relations are assuming an important area of study in Nigeria historiography. -

The Slave Ship Manuelita and the Story of a Yoruba

O tráfico de escravos africanos: Dossiê Novos horizontes Abstract: In 1833, a Cuban slave ship, the Manuelita, which The Slave Ship embarked over 500 slaves in Lagos was seized and condem- ned by the Anglo-Spanish slave court. After the personal details of the Africans ‘liberated’ from the ship had been Manuelita collected by court officials some of them were transported aboard the same ship to Trinidad as indentured workers and the Story and apprentices. Drawing on materials from the African Origins Database this paper investigates who these Africans of a Yoruba were, where they came from, and what their stories highli- ght about slaving operations in the Lagos hinterland and Community, the Americas in the age of abolition. 1833-1834 Keywords: slave trade, Cuba, Yoruba. O Navio Negreiro Manuelita e a Estória de Uma Comunidade Iorubá, 1833-1834 Olatunji Ojo [1] Resumo: Em 1833, um navio negreiro cubano, o Manuelita, que embarcou mais de 500 escravos em Lagos, foi captu- rado e condenado pela corte de comissão mista anglo-es- panhola. Após a informação pessoal dos africanos “liber- tados: do navio foi coletada pelos oficiais da corte, alguns deles foram transportados no mesmo navio para Trinidad como aprendizes e trabalhadores compulsórios por tempo determinado. Baseando-se em informações do banco da dados Origens Africanas, este artigo buscar examinar quem eram esses africanos, de onde eles vieram, e o que a estória deles traz à luz sobre as operações escravistas no interior de Lagos e nas América durante o período da abolição. Palavras-chave: tráfico de escravos, Cuba, Iorubá. Article received on 28 February 2017 and approved for publication on 03 March 2017.