Yukoner No.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dwellings, Yukon and Census Subdivision

Yukon Bureau of Statistics 2÷9#1$>0-2+6&±8<3π7£5‡9≈1∞^ Population and Dwellings Census 2011 Population Growth by Province and Territory Highlights (2006 to 2011 Census Counts) • 33,897 people were counted in Yukon in May 2011. 11.6% • Yukon’s population growth of 11.6% between the 10.8% 2006 and 2011 census years was the highest in Canada average = 5.9% 8.3% Canada. 7.0% 6.7% 5.7% 5.2% • 80% of Yukon’s population growth took place in 4.7% Whitehorse. 3.2% 2.9% 1.8% • The total number of Yukon dwellings occupied by 0.9% 0.0% usual residents grew by 11.9%. YT AB NU BC SK ON MB QC PE NB NL NS NT In May 2011, Statistics Canada conducted a census of Cana- one exception (1996 to 2001 census years; due mainly to the dian residents. The data collected covered Canada, the prov- Faro mine closure). inces and territories, and down to community and municipal The growth in Yukon between 2006 and 2011 (which oc- areas. curred mainly in Whitehorse) was related to a net increase in In Yukon, data is categorized into 37 geographic census sub- the number of immigrants and non-permanent residents, as divisions. These subdivision types range from city down to well as a net increase in inter-provincial migration. very small parcels of land which have historic signifi- cance but no current population. Yukon Census Populations and Percent Growth The release of population and dwelling counts data (1956 to 2011 Census Counts) from the 2011 Census of Population marks the first of 40,000 40.0% four releases in 2012. -

GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH at the YUKON ARCHIVES

GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE YUKON ARCHIVES A Listing of Available Resource Material Revised Edition AUGUST 2003 Originally published in 1985 under title: Genealogy sources available at the Yukon Archives c2003, Yukon Archives, Cultural Services Branch, Dept. of Tourism and Culture, Yukon Territory Canadian Cataloguing in Publication data Yukon Archives. Genealogical sources available at the Yukon Archives Rev. ed. ISBN 1-55362-169-7 Includes index 1. Yukon Archives--Catalogs. 2. Archival resources--Yukon Territory--Catalogs 3. Yukon Territory--Genealogy--Bibliography--Catalogs. 4. Yukon Territory--Genealogy--Archival resources--Catalogs. I. Title. CS88.Y84 2003 016.929 371 91 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................I-1 STARTING YOUR SEARCH ..................................................................................................................I-1 GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH AT YUKON ARCHIVES....................................................................I-2 FAMILY HISTORY INFORMATION SOURCES..................................................................................I-3 RESEARCH MATERIALS FOUND AT THE ARCHIVES....................................................................I-4 HOW TO READ THE BIBLIOGRAPHICAL CITATIONS ...................................................................I-5 CHECKLIST OF POPULAR FAMILY HISTORY SOURCES ..............................................................I-6 PUBLISHED SOURCES.......................................................................................................... -

Arctic Airports and Aerodromes As Critical Infrastructure

October 30, 2020 Arctic Airports and Aerodromes as Critical Infrastructure Christina Bouchard, Graduate Fellow and Program Manager: Critical Infrastructure in Canada’s Arctic Territories Key Considerations Many Arctic communities were formed as coastal settlements and continue to rely heavily on air or naval transportation modes. Notably, the territory of Nunavut (NU) includes island communities where air infrastructure plays a critical role in community resupply in the absence of a highway system. It is anticipated that the rapid advancement of climate change will result in permafrost melt, sea ice melt and changing weather patterns. The ground upon which runways, buildings and other infrastructure are constructed will shift and move as the permafrost melts. Capital planning studies have also identified shortfalls with runway lighting systems and power supply, critical for safety where visibility is challenging. Both the extended periods of darkness in the North and the increasing prevalence of severe wind and weather events heighten the need for modern lighting systems. In addition to climate change considerations, the 2020 emergence of the novel COVID-19 virus has also drawn attention to the essential nature of airports in Nunavut for medical flights1. Private companies providing air services, have experienced pressures following the emergence of the virus. The pandemic circumstances of COVID-19 exposed, and brought to question, underlying systemic assumptions about the profitability of providing medically critical air travel services to remote locations. Purpose This policy primer describes the state of existing and planned Arctic aeronautical facilities. The overarching challenge of remoteness faced by many northern communities is discussed to understand the critical nature of air travel infrastructure in remote communities. -

Yukon Residential Schools Bibliography

Yukon Residential Schools Bibliography Yukon Archives, Anglican Church, Diocese of Yukon fonds, 86/61 #690. Last modified: 2019-05-07 YUKON RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS BIBLIOGRAPHY: A LIST OF DOCUMENTS HELD AT THE YUKON ARCHIVES Yukon Archives November 2011 5 © 2011, Government of Yukon, Yukon Tourism and Culture, Yukon Archives, Box 2703, Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 Photo Credit Cover: View of Chooutla School. Yukon Archives, Anglican Church, Diocese of Yukon fonds, 86/61 #690. Cataloguing–in–publication Yukon Archives Bibliography of Yukon residential schools, a list of documents held at the Yukon Archives. Whitehorse, Yukon: Yukon Tourism and Culture, Yukon Archives, c2011. ISBN: 978-1-55362-523-0 1. Indians of North America--Yukon--Residential schools-- Bibliography. 2. Indians of North America--Education--Yukon-- Bibliography. 3. Native peoples--Education--Yukon--Bibliography. I. Title. II. Title: List of documents held at the Yukon Archives. Z1392 Y9 Y96 2011 016.371829'9707191 C2011-909034-1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 PUBLISHED MATERIAL ...................................................................................................... 3 BOOKS & PAMPHLETS ................................................................................................................ 3 NEWSPAPER ARTICLES ............................................................................................................ 10 PERIODICALS .............................................................................................................................. -

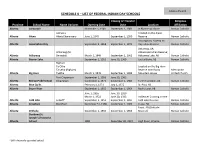

Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools

SCHEDULE K – LIST OF FEDERAL INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS Closing or Transfer Religious Province School Name Name Variants Opening Date Date Location Affiliation Alberta Alexander November 1, 1949 September 1, 1981 In Riviere qui Barre Roman Catholic Glenevis Located on the Alexis Alberta Alexis Alexis Elementary June 1, 1949 September 1, 1990 Reserve Roman Catholic Assumption, Alberta on Alberta Assumption Day September 9, 1968 September 1, 1971 Hay Lakes Reserve Roman Catholic Atikameg, AB; Atikameg (St. Atikamisie Indian Reserve; Alberta Atikameg Benedict) March 1, 1949 September 1, 1962 Atikameg Lake, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Beaver Lake September 1, 1952 June 30, 1960 Lac La Biche, AB Roman Catholic Bighorn Ta Otha Located on the Big Horn Ta Otha (Bighorn) Reserve near Rocky Mennonite Alberta Big Horn Taotha March 1, 1949 September 1, 1989 Mountain House United Church Fort Chipewyan September 1, 1956 June 30, 1963 Alberta Bishop Piché School Chipewyan September 1, 1971 September 1, 1985 Fort Chipewyan, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Blue Quills February 1, 1971 July 1, 1972 St. Paul, AB Alberta Boyer River September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Rocky Lane, AB Roman Catholic June 1, 1916 June 30, 1920 March 1, 1922 June 30, 1933 At Beaver Crossing on the Alberta Cold Lake LeGoff1 September 1, 1953 September 1, 1997 Cold Lake Reserve Roman Catholic Alberta Crowfoot Blackfoot December 31, 1968 September 1, 1989 Cluny, AB Roman Catholic Faust, AB (Driftpile Alberta Driftpile September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Reserve) Roman Catholic Dunbow (St. Joseph’s) Industrial Alberta School 1884 December 30, 1922 High River, Alberta Roman Catholic 1 Still a federally-operated school. -

Yukon Bureau of Statistics Other Census

Yukon Bureau of Statistics 2÷9#1$>0-2+6&±8<3π7£5‡9≈1∞^ Population and Dwellings Census 2016 Highlights • The 2016 Census of Population counted 35,874 people in Yukon as of May 10, 2016. • Yukon’s population growth rate of 5.8% between the censuses of 2011 and 2016 was the fourth-highest in Canada, tied with Manitoba. • The population growth in the Whitehorse census subdivision (CSD) accounted for 91.5% of Yukon’s population growth. • Between the censuses of 2011 and 2016, the total number of private dwellings in Yukon increased 10.6% while the number of private dwellings occupied by usual residents grew by 7.8%. In May 2016, Statistics Canada conducted the 2016 Census of Population to count people according to their usual place of residence as of May 10, 2016, and to collect other relevant information. The first set of results with population (not adjusted for under-coverage) and dwelling counts were released on February 8, 2017. This was the first of six releases of census results in 2017. For Yukon, the counts are grouped into 36 census subdivisions (CSDs). The CSDs represent municipalities as determined by provincial/territorial legislation or areas treated as municipal equivalents for statistical purposes (e.g., Settlements and unorganized territories). The population growth rate in Yukon between the censuses Population Growth by Province and Territory of 2011 and 2016 was 5.8%. This was down from the growth (2011 to 2016 Census Counts) rate of 11.6% between the censuses of 2006 to 2011. The 12.7% 11.6% slower growth rate was mainly due to interprovincial migra- tion losses. -

Fin-Language-Census-2016.Pdf

Yukon Bureau of Statistics 2÷9#1$>0-2+6&±8<3π7£5‡9≈1∞^ Language Census 2016 Highlights • In the 2016 Census, 99.6% of all Yukoners (excluding institutional residents) reported knowledge of at least one of- ficial language: 85.6% knew English only; 13.8% both English and French; 0.2% French only; and 0.4% knew neither English or French. • In Yukon, 805 people reported Tagalog (Pilipino, Filipino) as their only mother tongue. • In 2016, 4.5% of Yukoners reported speaking only a non-official language most often at home. Knowledge of Official Languages According to the 2016 Census, 99.6% of all Yukoners (exclud- Between 2011 and 2016, the percentage of Yukon’s popu- ing institutional residents) reported knowledge of at least lation who had knowledge of both English and French in- one official language: 85.6% knew English only; 13.8% both creased 0.7 percentage points (from 13.1% in 2011 to 13.8% English and French; 0.2% French only; and 0.4% knew nei- in 2016). Nationally, the rate of bilingualism increased 0.4 ther English or French. percentage points over the same period (from 17.5% in 2011 to 17.9% in 2016). Knowledge of Both Official Languages, Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2016 Knowledge of English and French, By Age Group and Sex, Yukon, 2016 44.5% 1,800 33.9% 1,600 1,400 1,200 Canada (17.9%) 1,000 13.8% 12.7% 10.5% 11.2% 10.3% 8.6% 800 6.6% 6.8% 5.0% 4.7% 4.3% 600 400 NFLD PEI NS NB QC ON MB SK AB BC YT NWT NU 200 0 Total - Sex Male Female In every province and territory, more than 97.0% of the popu- 0 to 14 years 15 to 24 years 25 to 44 years lation reported having knowledge of at least one of Canada’s 45 to 64 years 65 to 74 years 75 years and over official languages, with the exceptions of Nunavut (94.3%) and British Columbia (96.7%). -

William C. and Frances P. Ray Slides, B2016.006

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: William C. and Frances P. Ray Slides COLLECTION NUMBER: B2016.006 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1944-1993 Extent: 5 boxes; 3.25 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): William C. Ray, Frances Ray Administrative/Biographical History: Frances E. Ray (née Pickolick) was born on 16 February 1921 in Grangeville, Idaho to Elizabeth and Frank Pickolick. She relocated to Alaska in 1944 and worked at Fort Richardson as a secretary for Bill Ray. They were married on 20 May 1945. Frances went on to teach at Anchorage High School (later West High School) and retired in 1976. Frances also worked for a period of time as the registrar at the Anchorage Community College. She was an avid volunteer in her later years at the Anchorage Museum and the Anchorage Convention and Visitor Bureau. She passed away on 17 August 2005.1 William “Bill” C. Ray was born in Gough, Texas on 3 November 1916 to Nason and Fern Cornelius Ray. Bill moved to Alaska in 1939, and served as a civilian employee in the Depot Supply at Fort Richardson during World War II.2 He joined the U.S. Air Force Civil Service, and worked as a property administrator for the White Alice project from its beginning until his 1 “Frances Ray Obituary.” Anchorage Daily News, Thursday 25 August 2005. -

The Yukon Territory CONTENTS

ALBERTA FRoVINCIAL LIBRARY The Yukon Territory CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. Historical Sketch .... .. ... .. ... ... ........... ..... .... .. .. .... .. 7 II. Constitution and Government... .. 19 Ill. Placer Deposits . 21 (1) Gold .. .. .... ... .. ........ ... .... ... ........... .. ..... 21 (2) Copper. 24 (3) Tungsten . 24 IV. Placer Mining Methods and Operators... 27 (1) Sinking and Drifting.. 27 (2) Ground Sluicing. ?:l (3) Hydraulicking. 27 (4) Dredging. 27 (5) Thawing.. 27 (6) Individual operators ...... ......... '. 30 (7) Yukon Gold Company. 30 (8) Burrall and Baird.. 34 (9) North West Corporation.. 35 V. Lode Deposits. 37 (1) General Information. 38 (2) Mayo-Keno District. 38 (3) Upper Beaver District... 47 (4) Klondike District . .. .... ... :. 48 (5) Whitehorse District . ... .... .. .. .. .. '. ' . 50 (6) Wheaton District. 52 (7) Windy Arm District. 54 VI. Water:-powers.. .. ... ..... .. ..... ... ... .. .... ... ......... .. .. .. 59 VII. Agriculture....... 63 VIII. Game, Fur and Fish.. 67 IX. Transportation.. ... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. ... .. .... .. ... .. .. 71 (1) Rail and water; freight-express ... ... .... .. .... : . 71 (2) Roads and trails... .. 74 X. Communication.... ......... .. 77 (1) Telegraph, Telephone and Wireles~ . 77 XI. General Information. 79 (1) Climate ... .... ... .... .. .... ....... .. .. .. ... , . 79 XII. Aborigines.... .. .. ... .. .. .. 81 XIII. Churches and Hospitals... 83 XIV. Education.... .. ............ ... .... .. ... .. .. .. ....... .. .. 89 XV. Appendices.. .. .... .. ... .... .... ..... -

Daily Routine Tributes

March 28, 2011 HANSARD 8059 Yukon Legislative Assembly land, claiming taxes and debts. This was always a sore spot for Whitehorse, Yukon Sue and she often talked about this with her children. Monday, March 28, 2011 — 1:00 p.m. Sue reconnected with her childhood friend, Alex Van Bib- ber, in 1943. Soon they married and had two more daughters Speaker: I will now call the House to order. At this and welcomed Alex’s son Richard into the fold. She and Alex time, we will proceed with prayers. lived at Champagne throughout their 67-year marriage. Sue and Alex made a good team, having both been raised in the bush in Prayers a large family who, even as children, were expected to work as hard as their parents. These skills made them successful big- DAILY ROUTINE game outfitters from 1948 to 1968. During the winter, they Speaker: We will proceed at this time with the Order both ran trap-lines to supplement the seasonal outfitting income Paper. I think it’s self-evident to ask all members of the audi- and maintain their healthy lifestyles. The southwest Yukon ence to turn their cellphones off. from Wolverine Creek to Kusawa Lake was home to both of Tributes. them and they knew the land, the trails and the ways of the TRIBUTES animals that lived there. An excellent cook, Sue’s cinnamon buns were gone as In remembrance of Susan Van Bibber soon as they came out of the oven. Her moose stew was in- Hon. Mr. Lang: Before I commence with my tribute, credible. -

Rolf and Margaret Hougen Fonds, 2009/81 (Yukon Archives Caption List)

Rolf and Margaret Hougen fonds acc# 2009/81 YUKON ARCHIVES PHOTO CAPTION LIST Caption information supplied by donor. Information in square [ ] brackets provided by Archivist. Further details about these photographs are available in the Yukon Archives Descriptive Database at www.yukonarchives.ca PHO 663 YA# orig# Description: 2009/81 #1 5-2 Senator Robert Kennedy standing in front of Sam McGee's cabin Senator Robert Kennedy standing in front of Sam McGee's cabin in Whitehorse during his 1965 trip to climb Mount Kennedy in honour of his brother, President John F. Kennedy. [Kennedy is holding a camera in his hand. Sign over door reads "Sam McGee's Cabin Built in 1899". Antlers are hung above the sign.] - [Mar-May] 1965. 2009/81 #2 [Senator Robert Kennedy with Commissioner Gordon Cameron at Whitehorse airport] [Senator Robert Kennedy being met by Commissioner Gordon Cameron at Whitehorse airport. A man with a camera is nearby. A helicopter is in the background.] - [Mar-May] 1965. 2009/81 #3 [Senator Robert Kennedy at Whitehorse airport] [Senator Robert Kennedy at Whitehorse airport. Civilian and military photographers are nearby. A helicopter is in the background.] [Additional information provided by Rolf Hougen in 2011:] Behind Kennedy is Eric Wienecke, who was associated with Hougen's for many years. - [Mar-May] 1965. last modified on: 2020-12-20 status: Approved 1 Rolf and Margaret Hougen fonds acc# 2009/81 YUKON ARCHIVES PHOTO CAPTION LIST Caption information supplied by donor. Information in square [ ] brackets provided by Archivist. Further details about these photographs are available in the Yukon Archives Descriptive Database at www.yukonarchives.ca PHO 663 YA# orig# Description: 2009/81 #4 2-4 [Senator Robert Kennedy flanked by two RCMP officers at Whitehorse airport] [Senator Robert Kennedy standing with two RCMP officers at Whitehorse airport. -

Population & Dwellings PM

Census ‘96 Population and Dwelling Counts The following statistics are the first release from the 1996 Census of Canada which occurred on May 14, 1996. 1 Highlights ● The population of the Yukon, as enumerated by the 1996 Census, on May 14, 1996, was 30,766, just under 3,000 (10.7%) more than in 1991 (27,797). ● In 1996, 60% of the Yukon’s population lived in urban areas, almost the same as in 1991. ● The number of occupied private dwellings in the Yukon climbed to 11,584 in 1996, from 9,915 in 1991. Population and Dwelling Counts 2 Canada, Provinces and Territories 1996 Census 1991 Census '91 to '96 1996 Census Population Population % Change Dwellings Canada 28,846,761 27,296,859 5.7 10,899,427 Newfoundland 551,792 568,474 -2.9 187,406 Prince Edward Island 134,557 129,765 3.7 48,630 Nova Scotia 909,282 899,942 1.0 344,779 New Brunswick 738,133 723,900 2.0 272,915 Quebec 7,138,795 6,895,963 3.5 2,849,149 Ontario 10,753,573 10,084,885 6.6 3,951,326 Manitoba 1,113,898 1,091,942 2.0 421,096 Saskatchewan 990,237 988,928 0.1 375,740 Alberta 2,696,826 2,545,553 5.9 984,275 British Columbia 3,724,500 3,282,061 13.5 1,433,533 Yukon 30,766 27,797 10.7 11,584 Northwest Territories 64,402 57,649 11.7 18,994 3 1996 Census Population May 1996 Population 4 Estimates, Yukon -------Population------- Health Care Files % 1996 1991 Change Population Yukon 30,766 27,797 10.7 Yukon 32,682 Beaver Creek 131 104 26.0 Beaver Creek 140 Burwash Landing 58 77 -24.7 Burwash Landing 84 Carcross* 277 273 1.5 Carcross 424 Carmacks 466 349 33.5 Carmacks 476 Dawson 1,287 1,089 18.2 Dawson 2,013 Destruction Bay 34 32 6.3 Destruction Bay 47 Faro 1,261 1,221 3.3 Faro 1,255 Haines Junction 574 477 20.3 Haines Junction 821 Ibex Valley 322 240 34.2 Ibex Valley - Keno Hill 24 36 -33.3 Keno Hill - Mayo 324 243 33.3 Mayo 501 Mt.