Russel Frink

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naval Shipbuilding Expansion: the World War II Surface Combatant Experience

Naval Shipbuilding Expansion: The World War II Surface Combatant Experience Dr. Norbert Doerry1 (FL), Dr. Philip Koenig1, P.E. (FL) 1. Naval Sea Systems Command, Washington, D.C. From the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991 to the present day, the U.S. Navy has exercised uncontested control of the high seas. In the absence of peer naval competition, the surface combatant force was re-oriented towards land attack and near-shore operations in support of power projection. This historically unprecedented strategic situation appears to be nearing its end with the rapid growth and reach of the new 21st century Chinese navy and the reinvigoration of the Russian fleet. In response, U.S. Navy strategic planning has been re-balanced towards naval warfare against growing peer competitors, and the naval shipbuilding program is being ramped up. The last time this took place was in the run-up to World War II. What can we learn from that experience, so that the currently planned buildup can be as effective as possible? This paper offers an introductory examination of how the U.S. planned, designed, and built the surface combatant fleet during the interwar period (1920-1941), with a focus on destroyers. After accounting for differences in warship complexity and the industrial and shipbuilding capabilities of the United States of the 1930’s and 1940’s as compared to today, lessons for today’s surface combatant designers and program managers are identified and discussed. Recommendations are made for further work. KEY WORDS nuclear, industrial-scale war can no longer be dismissed. -

Military Sun Press, Published Twice Edition of the Military Sun Press, Treat- HAWAII MARINE Is Not Published

NOTICE TO HAWAII MARINE READERS We hope you will enjoy this special readers during the holiday season when The Military Sun Press, published twice edition of the Military Sun Press, treat- HAWAII MARINE is not published. each year, is in no way connected to the ed especially for HAWAII MARINE U.S. Marines or the U.S. government. Hawaii Marine WEEK OF JANUARY 5-11, 1995 Military Sun Press BRIEFLY Recycling: Veterans Day honor Military families The Golden Dragons of Task Force 5th Bat- participate in new talion, 14th Infantry celebrated Veterans Day Nov. 10 with a ceremony performed at South Camp, near Sharm El Sheik, Sinai, Egypt. garbage program The ceremony was conducted at the South Camp amphitheater and began with the familiar The recently closed Waipahu sounds of Lee Greenwood's "God Bless the incinerator has created a need to USA." recycle more refuse, and military The Task Force Chaplain, Charles Ha Ilin, personnel coming to the rescue. delivered the invocation and led the group in Roughly one-half of military fami- the " Lord's Prayer." Sgt. 1st Class Jeffrey Stray- lies who live in government quarters er, operations non commissioned officer in now participate in active recycling charge, read the 23rd Psalm. programs. Thanks to an Army initia- Presiding over the ceremony was the Task tive, all 20,151 quarters will be ser- Force Executive Officer, Maj. John A. Kardos, viced by a new refuse and recycling who delivered the keynote address. system by early this year. In his address, Kardos called on the attendees The new system encourages the to "remember the tragedies of war, the promise military's 70,000 family housing resi- of peace and those who served so selflessly." dents to recycle and will also save The audience was asked to remember those money spent on refuse removal and who lost their lives during their service with the disposal. -

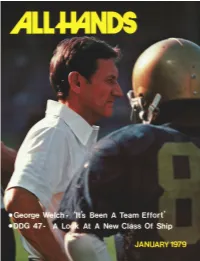

George Welsh, Is Thesubject of a Feature Beginning on Page 16

Ohio, the nation’s,first Trident mi.ssile,firing.suh- rnarine, clwarfi the SSN 688-class attack suh- marine Jacksonville (SSN 699) ufloat in graving ~l~~~~k,follo~~inglaunc~hingin Nvvenlher at Groton. Conn. Ohio i.s .schetlulecl,fi~r/aunc,hinR this year. (General Dvnarnic,.s photo.) ALL WIND6 MAGAZINE OF THE US. NAW"56th YEAR OF PUBLICATION JANUARY 1979 NUMBER 744 Chief of Naval Operations: ADM Thomas B. Hayward Chief of Information: RADM .David M. Cooney OIC Navy Internal Relations Act.: CAPT James E. Wentz Features 6 DDG 47"SHE MAY LOOK THE SAME BUT ... A look at a new class of ship for the 1980s Page 10 10 FAMILY ADVOCACYPROGRAM Expanded program deals with spouse as well as child 13 NAW RELIEFHITS 75 Dispensing aid without benefit of a budget 16 GEORGEWELSH-"IT'S BEEN A TEAM EFFORT" His thoroughness is his mark of excellence 24 ENERGYCONSERVATION EFFORTS REAP AWARDS Sea and shore commands win SecNav Energy Awards 28 GREATLAKES CRUISE Mid-America responds to visits by three destroyers 30 SOUNDFOCUSING ON BLOODSWORTH ISLAND Chesapeake Bay range has served Navy since 1942 34 MEDICAL AND HEALTHCARE Second in a new series of Navy Rights and Benefits 42 MINORITY RECRUITMENTAT INDIAN HEAD One individual's novel approach to a difficult task 46 PLANNING FOR TOMORROW Paae 34 What's new and better aboard Pacific Fleet ships Departments Currents-2; Bearings-22; Mail Buoy-48 Covers Front: Navy's winning football coach, George Welsh, is thesubject of a feature beginning on page 16. Photo by D.B. Eckard. Back Sunset on Bloodsworth Island. -

South Pacific Destroyers: the United States Navy and the Challenges of Night Surface Combat

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2009 South Pacific esD troyers: The nitU ed States Navy and the Challenges of Night Surface Combat in the Solomons Islands during World War II. Johnny Hampton Spence East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Spence, Johnny Hampton, "South Pacific eD stroyers: The nitU ed States Navy and the Challenges of Night Surface Combat in the Solomons Islands during World War II." (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1865. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1865 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Pacific Destroyers: The United States Navy and the Challenges of Night Surface Combat in the Solomons Islands During World War II ____________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ____________________________ by Johnny H. Spence, II August 2009 ____________________________ Dr. Ronnie Day, Chair Dr. Emmett Essin Dr. Stephen Fritz Keywords: Destroyers, World War II, Pacific, United States Navy, Solomon Islands ABSTRACT South Pacific Destroyers: The United States Navy and the Challenges of Night Surface Combat in the Solomons Islands during World War II by Johnny H. -

The Evolution of the US Navy Into an Effective

The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942 - 1943 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jeff T. Reardon August 2008 © 2008 Jeff T. Reardon All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation titled The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942 - 1943 by JEFF T. REARDON has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Marvin E. Fletcher Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences iii ABSTRACT REARDON, JEFF T., Ph.D., August 2008, History The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942-1943 (373 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Marvin E. Fletcher On the night of August 8-9, 1942, American naval forces supporting the amphibious landings at Guadalcanal and Tulagi Islands suffered a humiliating defeat in a nighttime clash against the Imperial Japanese Navy. This was, and remains today, the U.S. Navy’s worst defeat at sea. However, unlike America’s ground and air forces, which began inflicting disproportionate losses against their Japanese counterparts at the outset of the Solomon Islands campaign in August 1942, the navy was slow to achieve similar success. The reason the U.S. Navy took so long to achieve proficiency in ship-to-ship combat was due to the fact that it had not adequately prepared itself to fight at night. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

''The Elsie Item'' Official Newsletter of the Uss Landing Craft, Infantry, National Association, Inc

''THE ELSIE ITEM'' OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE USS LANDING CRAFT, INFANTRY, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, INC. JULY, 2003 ESTABLISHED MAY NORFOLK, ISSUE #45 14-18, 1991, VA I I THE COLOR GUARD AT THE LCI MEMORIAL SERVICE (See Page 2) "THE ELSIE ITEM" Number45 July, 2003 Again it's a pleasureWelcome to welcome Aboard! aboard a new "draft"· of shipmates, freshly arrived and ready for service and fellow Official Newsletter of the USS LC! National Association, a ship in the LCI Nationa.l Organization. non-profit veteran's organization. Membership in the USS LCI National Assciation is open to any U.S. Navy or U.S. OK, guys, stow your gear in your lockers, get your paint Coast Guard veteran who served aboard a Landing Craft, scrapers and follow me! Infantry. Associate Membership, without voting privileges, is offered to others. New Members: Published quarterly by the USS LCI National Association. John P. Cummer, Editor. Any material for possible publica LCI Name/Rate/Residence tion should be sent to the Editor at 20 W. Lucerne Circle, Orlando, FL 32801. AKA 15 David A. McCaffrey, BMIC, Framingham, MA ? William G.Albee, Madison, OH 24 Ronald H. Smith, MoMM JC, Benton Harbor, MI This fine color Aboutguard from the Lhc Cover Washington Picture: Ceremonial Unit made 369 Clifford Richard, Clearwater. FL au especially finecontribution to our memorial service at the Navy 406 Edward DeChant, Jasper, AR Memorial. In visiting the memorial afterwards, we were pleased to 664 William C.(Mickey) Sherr, LTJG, see the pictures and exhibits commemorating LCis. We tend to think, Phoenix, AR not without cause, that for many people, in and out of the Navy, 687 Hassel Justice, GM3C, Pikesville, KY LCis are a long forgotten ship of the far-distant past. -

Swarming in Warfare and the Battle of Surigao Strait; a Paradigm for 21St Century Warfare?

Swarming in Warfare and the Battle of Surigao Strait; A Paradigm for 21st Century Warfare? Terrence P. McGarty1 Abstract There are many differing strategic ways of attacking an enemy. The ways of doing this have varied over time and as technology has changed the ways of doing the attacks have themselves changed. A recent conception called swarming assumes a highly distributed but highly interconnected, inter-netted, attack force, which has significant flexibility during the attack. It is argued that the swarming approach is new and is predicated upon the technological advances in command, control, communications, computing, and intelligence. We argue herein that there was an initial example of swarming at the Battle of Surigao Strait. Ironically, the same day, on the Samar Island battle, the forces under the fleet admiral, 7th Fleet, Admiral Kinkaid, did not use what had been used just hours before and was almost devastated by the Japanese attack through the San Bernadino Straits. These two battles are simultaneous examples of two distance strategies, one swarming and the second nearly resembling a classic melee. This paper examines the Battle of Surigao Strait; with lessons learned both positive and negative. Contents 1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................3 2 Swarming Defined ...............................................................................................................................................5 -

The Ledger and Times Supplement, Part 2, June 6, 1946

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 6-6-1946 The Ledger and Times Supplement, Part 2, June 6, 1946 The Ledger & Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger & Times, "The Ledger and Times Supplement, Part 2, June 6, 1946" (1946). The Ledger & Times. 717. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/717 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. na* Ira 4 S -17 • * )46 •Pki• re- 'CES 1 day ho The to_230 s r"st st. 5 2 as b Pages t. Zone tday - YOUR PROGRESSIVE HOME NEWS- STOPS AT EXPIRATION DATE Ing-1 leaven FOR OVER HALF A CENTURY Murray, Kentucky, Thursday Afternoon, June 6, 1946 Vol. XVI; No. 23 •-•'even From County Attend State Meet 58 Die, 200 Hurt As Fire noway County 4-H Club win- will go tq. -Lexington Mon. HEROES WORLD WAR II, CALLOWAY COUNTY June 10, to attend the 23rd Hits Chicago Loop Hotel; ial Junior Week, which will .eld on the University of Ken- campus. I- was drafted E. PAlLMER entered PVT. DALTON D. 'PARKER y ELBERT PACE amtoN service Nov 16, 1941. and Oct 27, 1942. service Oct. 13, 1943 entered lose going are: Janet Key and • served with Co. "A" 815th Avia- Hopkinsville Men Victims • tion Engineer Battalion until he Hutson. -

Fletcher Class Destroyers by Captain George

Fletcher Class Destroyers By Captain George Stewart, USN (RET) as reported on www.NavyHistory.com This is the first of a series of articles describing life in the 1950s on a World War II built Fletcher Class Destroyer. My connection to these ships began as I was approaching graduation from the Massachusetts Maritime Academy in August of 1956. Due to a change in legislation, it was suddenly announced that all of my class would be required to serve on active duty in the Navy for 3 years upon graduation. My orders turned out to be to the USS Halsey Powell (DD 686), a Fletcher Class Destroyer home ported in San Diego, California. At the time I had not quite reached my 21st birthday. The Fletcher class destroyers were authorized as part of the 1941-42 Shipbuilding Program. They incorporated many lessons learned from earlier classes of destroyers built during the 1930s and in the early stages of World War II, particularly relating to stability and sea keeping ability. During the 1930s, the Navy had produced a succession of “step deck” destroyer designs with raised forecastles. But the Fletcher Class reverted to a “flush deck” design like the destroyers of World War I. Most of the ships were initially assigned to the Pacific Fleet where they were to play a major role in the war. A total of 175 Fletcher Class Destroyers were commissioned between 4 June 1942 and 22 February 1945. The lead ship of the class was USS Fletcher (DD 445). Hull numbers ranged between 445 and 691 plus an additional block between 792 and 804. -

U.S. Navy Action and Operational Reports from World War II, Pacific Theater

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of U.S. Navy Action and Operational Reports from World War II, Pacific Theater Part 1. CINCPAC: Commander-in-Chief Pacific Area UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of World War II Research Collections U.S. Navy Action and Operational Reports from World War II Pacific Theater Part 1. CINCPAC: Commander-in-Chief Pacific Area Command Project Editor Robert Ë. Lester Guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data U.S. Navy action and operational reports from World War II. Pacific Theater. (World War II research collections) Accompanied by printed reel guides compiled by Robert E. Lester. Includes indexes. Contents: pt. 1. CINCPAC (Commander-in-Chief Pacific Area Command) (16 reels) -- pt. 2. Third Fleet and Third Fleet Carrier Task Forces (16 reels) -- pt. 3. Fifth Fleet and Fifth Fleet Carrier Task Forces (12 reels). 1. United States-Navy-History-World War, 1939-1945- Sources. 2. World War, 1939-1945-Naval operations, American-Sources. 3. World War, 1939-1945-Campaigns- Pacific Ocean-Sources. 4. United States-Navy-Fleet, 3rd-History-Sources. 5. United States-Navy-Fleet, 5th~History--Sources. I. Lester, Robert. [Microfilm] 90/7009 (E) 940.54'5973 90-956103 ISBN 1-55655-190-8 (microfilm : pt. 1) CIP Copyright 1990 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-190-8. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction v Scope and Content Note vii Source and Editorial Note ix Reel Index Reel! 1 Reel 2 3 Reel 3 7 Reel 4 10 Reel 5 11 Reel6 16 Reel? 17 ReelS 19 Reel 9 21 Reel 10 22 Reel 11 25 Reel 12 .- 26 Reel 13 ; 28 Reel 14 34 Reel 15 35 Reel 16 37 Subject Index 43 INTRODUCTION Fleet Admiral Chester W. -

Replacing Battleships with Aircraft Carriers in the Pacific in World War Ii

Naval War College Review Volume 66 Article 6 Number 1 Winter 2013 Replacing Battleships with Aircraft aC rriers in the Pacific in orW ld War II Thomas C. Hone Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Hone, Thomas C. (2013) "Replacing Battleships with Aircraft aC rriers in the Pacific in orldW War II," Naval War College Review: Vol. 66 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol66/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hone: Replacing Battleships with Aircraft Carriers in the Pacific in Wo REPLACING BATTLESHIPS WITH AIRCRAFT CARRIERS IN THE PACIFIC IN WORLD WAR II Thomas C. Hone his is a case study of operational and tactical innovation in the U.S. Navy Tduring World War II. Its purpose is to erase a myth—the myth that Navy tactical and operational doctrine existing at the time of Pearl Harbor facilitated a straightforward substitution of carriers for the battleship force that had been severely damaged by Japanese carrier aviation on 7 December 1941. That is not what happened. What did happen is much more interesting than a simple substi- tution of one weapon for another. As Trent Hone put it in 2009, “By early 1943, a new and more effective fleet organization had become available.” This more effective fleet, “built around carrier task forces,” took the operational initiative away from the Japanese and spearheaded the maritime assault against Japan.1 This was clearly innovation—something new.