Japanese Drumming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Festival As a Tourism Event- Stakeholders' Influence On

Traditional Festival as a Tourism Event: Stakeholders’ Influence on the Dynamics of the Sendai Tanabata Festival in Japan YUJIE SHEN JAP4693 - Master’s Thesis in Modern Japan Master’s programme 30 credits Autumn 2020 Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages (IKOS) University of Oslo December 15, 2020 Summary A new method of analyzing traditional Japanese festivals (matsuri) based on event studies is presented. Stakeholders’ influence and their interactions redefine narratives of tradition. In Japan, the urbanization of society has transformed matsuri into tourism-oriented events. However, the influence of touristification on tradition has not yet been fully explored. This paper offers a close examination of a case study about the dynamics of the Sendai Tanabata Festival. Local newspaper archives were used as the primary source and adopted the stake- holder theory and social exchange theory from event studies to examine stakeholders’ power and interests, as well as their relationships. The results discovered that it is the conflicts of festival stakeholders throughout the years that shaped the Sendai Tanabata Festival to what it is like today. Although festival organizers and local residents are key players, both domestic and foreign tourists’ influence should also not be neglected. The inheritance of traditional cul- ture depends on its original community i.e. local residents. Depopulation and aging social problems have shifted the weight of festival ownership to tourists, as they contribute to the economic revitalization and regional development. As a result, festival organizers tend to tai- lor the festival to tourists’ tastes, which often leads to change or loss of tradition’s original festive meaning or the invention of a new tradition. -

5Th Competition Award Ceremony Program 2010

The Japan Center at Stony Brook (JCSB) Annual Meeting JCSB-Canon Essay Competition Award Ceremony 10:00 – 11:15 a.m. (Chapel) 12:15 -1 p.m. (Chapel) Opening Remarks: Opening Remarks: Iwao Ojima, JCSB President Iwao Ojima, JCSB President & Chair of the Board Greetings: Mark Aronoff, Vice Provost, Stony Brook University Financial Report: Joseph G. Warren, Vice President & General Manager, Canon U.S.A.; Chairman & COO, Patricia Marinaccio, JCSB Treasurer & Executive Committee Canon Information Technology Services, Inc. Result of the Essay Competition: Eriko Sato, Organizing Committee Chair Public Relations: JCSB Award for Promoting the Awareness of Japan: Roxanne Brockner, JCSB Executive Committee Presenter: Iwao Ojima Patrick J. Cauchi (English teacher at Longwood Senior High School) The Outreach Program: Best Essay Awards: Gerry Senese, Principal of Ryu Shu Kan dojo, JCSB Outreach Program Director Moderator: Sachiko Murata, Chief Judge Presenters: Mark Aronoff, Joseph Warren, and Iwao Ojima High School Division Best Essay Award The Long Island Japanese Association: st Eriko Sato, Long Island Japanese Association (LIJA), JCSB Board Member 1 Place ($2,000 cash and a Canon camera) A World Apart by Gen Ishikawa (Syosset High School) nd 2 Place ($1,000 cash and a Canon camera) Journey to a Japanese Family by Ethan Hamilton (Horace Mann High School) Pre-College Japanese Language Program: rd Eriko Sato, Director of Pre-College Japanese Language Program, JCSB Board Member 3 Place ($500 cash and a Canon camera) What Japan Means to Me by Sarah Lam (Bronx High School of Science) Honorable Mention ($100 cash) Program in Japanese Studies: Life of Gaman by Sandy Patricia Guerrero (Longwood Senior High School) (a) Current Status of the Program in Japanese Studies at Stony Brook University: Origami by Stephanie Song (Fiorello H. -

Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection

Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division at the Library of Congress Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 2004 Table of Contents Introduction...........................................................................................................................................................iii Biographical Sketch...............................................................................................................................................vi Scope and Content Note......................................................................................................................................viii Description of Series..............................................................................................................................................xi Container List..........................................................................................................................................................1 FLUTES OF DAYTON C. MILLER................................................................................................................1 ii Introduction Thomas Jefferson's library is the foundation of the collections of the Library of Congress. Congress purchased it to replace the books that had been destroyed in 1814, when the Capitol was burned during the War of 1812. Reflecting Jefferson's universal interests and knowledge, the acquisition established the broad scope of the Library's future collections, which, over the years, were enriched by copyright -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Teachers' Notes:Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical

Teachers’ Notes: Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical Instruments Shakuhachi This Japanese flute with only five finger holes is made of the root end of a heavy variety of bamboo. From around 1600 through to the late 1800’s the shakuhachi was used exclusively as a tool for Zen meditation. Since the Meiji restoration (1868), the shakuhachi has performed in chamber music combinations with koto (zither), shamisen (lute) and voice. In the 20 th century, shakuhachi has performed in many types of ensembles in combination with non-Japanese instruments. It’s characteristic haunting sounds, evocative of nature, are frequently featured in film music. Koto (in Anne’s Japanese Music Show, not Taiko performance) Like the shakuhachi , the koto (a 13 stringed zither) ORIGINATED IN China and a uniquely Japanese musical vocabulary and performance aesthetic has gradually developed over its 1200 years in Japan. Used both in ensemble and as a solo virtuosic instrument, this harp-like instrument has a great tuning flexibility and has therefore adapted well to cross cultural music genres. Taiko These drums come in many sizes and have been traditionally associated with religious rites at Shinto shrines as well as village festivals. In the last 30 years, Taiko drumming groups have flourished in Japan and have become poplar worldwide for their fast pounding rhythms. Sasara A string of small wooden slats, which make a large rattling sound when played with a “whipping” action. Kane A small hand held gong. Chappa A small pair of cymbals Sasara Kane Bookings -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally. -

Season's Greetings & Goodbye to “Kodo Enews” Kodo One Earth

greeting eNEWS Issue 46 December 2013 Season’s Greetings & Goodbye to “Kodo eNews” Welcome to the final issue of Kodo eNews. This monthly journal began in December 2009 and it takes a bow now in December 2013. We realize that as the times change, many people wish to read articles online and share, tweet and post links to our concert information, stage photos and articles. So instead of creating our PDF email newsletter, we will focus more on our online content: our website, a new-look blog coming soon, and our English & Japanese Facebook pages and more. Kodo One Earth Tour 2013: Mystery (“Shishimai”) Thank you very much for subscribing to Kodo eNews and reading our news each month. The production team, our website in mid-December. For entangled with each other. As it past and present, have shared some of everyone who will join us in the near gradually reveals its true form, you their memories of eNews and favorite future for our “One Earth Tour” in anticipate encountering an amazing, things about Sado Island on page 8, as Japan and Europe, and other solo and beautiful but scary world. Three snakes a thank you message and goodbye to small ensemble performances, we look you all. wriggled themselves free from each forward to seeing you there! Thank other with glinted scales in the dim you all for your support to date and in At the end of November, the brand light. The sound of Taiko drumming advance for 2014 and beyond! new “One Earth Tour: Mystery” began resonates one’s heart beat and increases on Sado Island and is currently on tour in Japan until December 24th. -

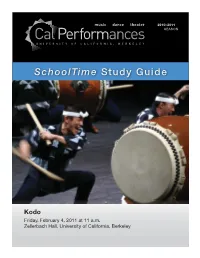

Kodo Study Guide 1011.Indd

2010–2011 SEASON SchoolTime Study Guide Kodo Friday, February 4, 2011 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime On Friday, February 4 at 11am, your class will att end a SchoolTime performance of Kodo (Taiko drumming) at Cal Performances’ Zellerbach Hall. In Japan, “Kodo” meana either “hearbeat” or “children of the drum.” These versati le performers play a variety of instruments – some massive in size, some extraordinarily delicate that mesmerize audiences. Performing in unison, they wield their sti cks like expert swordsmen, evoking thrilling images of ancient and modern Japan. Witnessing a performance by Kodo inspires primal feelings, like plugging into the pulse of the universe itself. Using This Study Guide You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Cal Performances fi eld trip. Before att ending the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the Student Resource Sheet on pages 2 & 3 for your students to use before the show. • Discuss the informati on on pages 4-5 About the Performance & Arti sts. • Read About the Art Form on page 6, and About Japan on page 11 with your students. • Engage your class in two or more acti viti es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect by asking students the guiding questi ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 11. • Immerse students further into the subject matt er and art form by using the Resource and Glossary secti ons on pages 15 & 16. At the performance: Your class can acti vely parti cipate during the performance by: • Listening to Kodo’s powerful drum rhythms and expressive music • Observing how the performers’ movements and gestures enhance the performance • Thinking about how you are experiencing a bit of Japanese culture and history by att ending a live performance of taiko drumming • Marveling at the skill of the performers • Refl ecti ng on the sounds, sights, and performance skills you experience at the theater. -

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: the Intercultural History of a Musical Genre

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre by Benjamin Jefferson Pachter Bachelors of Music, Duquesne University, 2002 Master of Music, Southern Methodist University, 2004 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences This dissertation was presented by Benjamin Pachter It was defended on April 8, 2013 and approved by Adriana Helbig Brenda Jordan Andrew Weintraub Deborah Wong Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung ii Copyright © by Benjamin Pachter 2013 iii Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre Benjamin Pachter, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation is a musical history of wadaiko, a genre that emerged in the mid-1950s featuring Japanese taiko drums as the main instruments. Through the analysis of compositions and performances by artists in Japan and the United States, I reveal how Japanese musical forms like hōgaku and matsuri-bayashi have been melded with non-Japanese styles such as jazz. I also demonstrate how the art form first appeared as performed by large ensembles, but later developed into a wide variety of other modes of performance that included small ensembles and soloists. Additionally, I discuss the spread of wadaiko from Japan to the United States, examining the effect of interactions between artists in the two countries on the creation of repertoire; in this way, I reveal how a musical genre develops in an intercultural environment. -

Nord-Honshū (Tōhoku)

TM Nord-Honshū (Tōhoku) Tōhoku Vorwort Selbst Besuchern, die schon in Japan waren, ist die Region Tōhoku, die den nördlichen Teil der Hauptinsel Honshū umfasst, oft gänzlich unbekannt. Dabei findet man hier all das, was Japan so faszinierend macht, und zudem ohne Besuchermassen. Bis vor kurzem war der Norden Honshūs tatsächlich schwierig zu bereisen – die öffentlichen Verkehrsmittel waren nicht so gut ausgebaut wie im südlichen Teil von Honshū, und auch die englisch- sprachige Ausschilderung ließ noch zu wünschen übrig. Dies alles ist nun im Vorfeld der Olympischen Sommerspiele in Tokio 2020 in Angriff genommen worden. Tōhoku begeistert mit großartigen Landschaften wie den Heiligen Drei Bergen Dewa San- zan in Yamagata, der berühmten Bucht von Matsushima nahe der Stadt Sendai, oder mit der Mondlandschaft um den Vulkan Osorezan. Für kulturell Interessierte bieten die UNESCO Weltkulturerbe-Stätten von Hiraizumi einen Einblick in vergangene Feudalzei- ten. Zahlreiche Feste wie das berühmte Nebuta Matsuri in Aomori oder das Reiter-Festi- val Soma Nomaoi locken jedes Jahr zigtausende Besucher in die Region. FASZINIEREND — BUNT — JAPAN Kurz: es gibt hier Vieles zu entdecken in einer bisher wenig besuchten Region Japans. Das findet inzwischen auch Lonely Planet: für das Jahr 2020 steht Tōhoku an dritter Stelle WIR FLIEGEN SIE HIN! unter den vom Lonely Planet an Top 10 gesetzten Regionen weltweit. Mit diesem Booklet möchten wir Ihren Appetit wecken – schauen Sie selbst, was Tōhoku Ihnen alles zu bieten GOEntdecken Sie Japans viele Facetten und tauchen Sie hat! ein in unvergessliche Erlebnisse. Viel Freude beim Entdecken wünscht Ihnen das JNTO Frankfurt-Team! Erleben Sie Japan bereits bei uns an Bord — 4x täglich und nonstop mit ANA von Deutschland nach Tokio und darüber hinaus. -

Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004

Music 17Q Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004 M W: 2:15 – 4:05 p.m., Braun 106 (M), Braun Rehearsal Hall (W) 4 units Course Syllabus Taiko, used here to refer to performance ensemble drumming using the taiko, or Japanese drum, is a relative newcomer to the American music scene. The emergence of the first North American groups coincided with increased activism in the Japanese American community and, to some, is symbolic of Japanese American identity. To others, North American taiko is associated with Japanese American Buddhism, and to others taiko is a performance art rooted in Japan. In this course we will explore the musical, cultural, historical, and political perspectives of taiko in North America through drumming (hands-on experience), readings, class discussions, workshops, and a research project. With taiko as the focal point, we will learn about Japanese music and Japanese American history, and explore relations between performance, cultural expression, community, and identity. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Students must attend all workshops and complete all assignments to receive credit for the course. Reaction Papers (30%) Midterm (20%) Research Project (40%) Attendance/Participation (10%) COURSE FEE $30 to partially cover cost of bachi, bachi bag, concert tickets, workshop fees, gas and parking for drivers. READINGS 1. Course reader available at the Stanford Bookstore. 2. Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Ronald Takaki. 1989. Penguin Books. GENERAL INFORMATION Instructors Steve Sano Linda Uyechi Office Braun 120 Office Phone 723-1570 Phone 494-1321 494-1321 (8 a.m. – 10 p.m.) Email sano@leland [email protected] 1 COURSE OUTLINE WEEK 1 (March 31) Wednesday Introduction: What is North American Taiko? Reading Terada, Y. -

Copyright by Angela Kristine Ahlgren 2011

Copyright by Angela Kristine Ahlgren 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Angela Kristine Ahlgren certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Drumming Asian America: Performing Race, Gender, and Sexuality in North American Taiko Committee: ______________________________________ Jill Dolan, Co-Supervisor ______________________________________ Charlotte Canning, Co-Supervisor ______________________________________ Joni L. Jones ______________________________________ Deborah Paredez ______________________________________ Deborah Wong Drumming Asian America: Performing Race, Gender, and Sexuality in North American Taiko by Angela Kristine Ahlgren, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To those who play, teach, and love taiko, Ganbatte! Acknowledgments I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to each person whose insight, labor, and goodwill contributed to this dissertation. To my advisor, Jill Dolan, I offer the deepest thanks for supporting my work with great care, enthusiasm, and wisdom. I am also grateful to my co-advisor Charlotte Canning for her generosity and sense of humor in the face of bureaucratic hurdles. I want to thank each member of my committee, Deborah Paredez, Omi Osun Olomo/Joni L. Jones, and Deborah Wong, for the time they spent reading and responding to my work, and for all their inspiring scholarship, teaching, and mentoring throughout this process. My teachers, colleagues, and friends in the Performance as Public Practice program at the University of Texas have been and continue to be an inspiring community of scholars and artists.