Teleopathy March 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Kuehn Dissertation Final Draft.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications PROSUMER-CITIZENSHIP AND THE LOCAL: A CRITICAL CASE STUDY OF CONSUMER REVIEWING ON YELP.COM A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Kathleen M. Kuehn © 2011 Kathleen M. Kuehn Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2011 The dissertation of Kathleen Kuehn was reviewed and approved* by the following: Patrick Parsons Professor of Telecommunications Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Michael Elavsky Assistant Professor of Film/Media Studies Matthew P. McAllister Professor of Film/Media Studies Michelle Miller-Day Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Marie Hardin Associate Professor of Journalism Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT Over the past few years, content developers searching for new markets have found a potentially lucrative consumer base in local and location-based services as new media platforms have begun to “expand” their focus to hyper-local place-based communities. This shift to “local 2.0” has given birth to “local listing sites,” an emerging social medium that converges the content of traditional Yellow Pages, consumer-generated content and the interactive features of social network sites. Such sites harness the productive power of “prosumers,” the hybrid subjectivity of new media users who simultaneously produce and consume online content (Tapscott & Williams, 2006). These sites capitalize on the productivity of users who create discourses through and about local consumption by voluntarily rating and reviewing local businesses and services, challenging the power of institutions traditionally responsible for the production of consumer culture and reputation management (e.g., local business owners, marketers, advertisers, professional critics). -

Alternative Investment Analyst Review

Alternative Investment Analyst Review EDITOR’S LETTER Hossein Kazemi WHAT A CAIA MEMBER SHOULD KNOW Alternative Beta: Redefining Alpha and Beta Soheil Galal, Rafael Silveira, and Alison Rapaport RESEARCH REVIEW OPEC Spare Capacity, the Term Structure of Oil Futures Prices, and Oil Futures Returns Hilary Till FEATURED INTERVIEW Mebane Faber on ETFs NEWS AND VIEWS The Time Has Come for Standardized Total Cost Disclosure for Private Equity Andrea Dang, David Dupont, and Mike Heale CAIA MEMBER CONTRIBUTION The Hierarchy of Alpha Christopher M. Schelling, CAIA INVESTMENT STRATEGIES Private Market Real Estate Investment Options for Defined Contribution Plans: New and Improved Solutions Jani Venter and Catherine Polleys PERSPECTIVES M&A Activity: Where Are We In the Cycle? Fabienne Cretin, Stéphane Dieudonné, and Slimane Bouacha Nowcasting: A Risk Management Tool Alexander Ineichen, CAIA VC-PE INDEX Mike Nugent and Mike Roth THE IPD GLOBAL INTEL REPORT Max Arkey Q3 2015, Volume 4, Issue 2 Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst Association® Call for Articles Article submissions for future issues of Alternative Investment Analyst Review (AIAR) are always welcome. Articles should cover a topic of interest to CAIA members and should be single-spaced. Additional information on submissions can be found at the end of this issue. Please email your submission or any questions to AIAR@CAIA. org. Chosen pieces will be featured in future issues of AIAR, archived on CAIA.org, and promoted throughout the CAIA community. Editor’s Letter Efficiently Inefficient The efficiency of market prices is one of the central questions in financial economics. The central thesis is that security markets are perfectly efficient, but this leads to two paradoxes: First, no one has an incentive to collect information in an efficient market, so how does the market become efficient? Second, if asset markets are efficient, then positive fees to active managers implies inefficient markets for asset management. -

Overview of the US Venture Capital Industry Alternative Assets

The Facts Overview of the US Venture Capital Industry alternative assets. intelligent data. Overview of the US Venture Capital Industry We provide a detailed look at the venture capital industry in the US, including fundraising, performance, deals and investors. Fundraising Fig. 1: Global Quarterly Venture Capital Fundraising, Fig. 2: US-Focused Quarterly Venture Capital Fundraising, Q1 Q1 2010 - Q3 2015 2010 - Q3 2015 140 60 120 50 100 40 80 30 60 20 40 20 10 0 0 Q1Q2Q3Q4Q1Q2Q3Q4Q1Q2Q3Q4Q1Q2Q3Q4Q1Q2Q3Q4Q1Q2Q3 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Date of Final Close Date of Final Close No. of Funds Closed Aggregate Capital Raised ($bn) No. of Funds Closed Aggregate Capital Raised ($bn) Source: Preqin Funds in Market Source: Preqin Funds in Market Fig. 3: Average Time Taken for First-Time Venture Capital Fig. 4: Average Time Taken for Established Venture Capital Funds to Reach a Final Close: Global vs. US-Focused Funds, Funds to Reach a Final Close: Global vs. US-Focused Funds, Q1 2010 - Q3 2015 Q1 2010 - Q3 2015 25 25 23 23 22 20 20 19 19 18 18 18 18 17 18 17 17 16 16 16 Global Global 15 15 14 Funds 13 Funds 13 12 12 12 11 10 9 10 US-Focused Close (Months) US-Focused Close (Months) Funds Funds 5 5 Average Time Taken to Reach a Final Time Taken Average Average Time Taken to Reach a Final Time Taken Average 0 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Q1 - Q3 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Q1 - Q3 2015 2015 Date of Final Close Date of Final Close Source: Preqin Funds in Market Source: Preqin Funds in Market Data Source: Preqin’s Funds in Market is the industry’s leading source of intelligence on private equity and venture capital fundraising. -

USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis…

5/4/2010 USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis… H-1B Approved Petitioners Fiscal Year 2009 The file below is a list of petitioners who received an approval in fiscal year 2009 (October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2009) of Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker, requesting initial H- 1B status for the beneficiary, regardless of when the petition was filed with USCIS. Please note that approximately 3,000 initial H- 1B petitions are not accounted for on this list due to missing petitioner tax ID numbers. Related Files H-1B Approved Petitioners FY 2009 (1KB CSV) Last updated:01/22/2010 AILA InfoNet Doc. No. 10042060. (Posted 04/20/10) uscis.gov/…/menuitem.5af9bb95919f3… 1/1 5/4/2010 http://www.uscis.gov/USCIS/Resource… NUMBER OF H-1B PETITIONS APPROVED BY USCIS IN FY 2009 FOR INITIAL BENEFICIARIES, EMPLOYER,INITIAL BENEFICIARIES WIPRO LIMITED,"1,964" MICROSOFT CORP,"1,318" INTEL CORP,723 IBM INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED,695 PATNI AMERICAS INC,609 LARSEN & TOUBRO INFOTECH LIMITED,602 ERNST & YOUNG LLP,481 INFOSYS TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED,440 UST GLOBAL INC,344 DELOITTE CONSULTING LLP,328 QUALCOMM INCORPORATED,320 CISCO SYSTEMS INC,308 ACCENTURE TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS,287 KPMG LLP,287 ORACLE USA INC,272 POLARIS SOFTWARE LAB INDIA LTD,254 RITE AID CORPORATION,240 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO,236 DELOITTE & TOUCHE LLP,235 COGNIZANT TECH SOLUTIONS US CORP,233 MPHASIS CORPORATION,229 SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES LIMITED,219 BLOOMBERG,217 MOTOROLA INC,213 GOOGLE INC,211 BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCH SYSTEM,187 UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND,185 UNIV OF MICHIGAN,183 YAHOO INC,183 -

Preqin Venture Capital Deals

Content Includes Preqin Special Report: Venture Capital May 2012 Venture Capital Deals Since the dot-com bubble and the emergence of new sectors of interest, the VC deal market has evolved considerably. What are the notable trends in industry, stage and size? What have been the largest venture capital financings and exits? Fund Managers and Fundraising How have venture capital fundraising efforts been affected by the recent financial market turmoil? We analyze the make-up of the fund manager universe, investigate the key historical fundraising trends and assess the current market for VC funds looking to attract capital. Venture Capital Investors Investors remain committed to financing innovation across the world; however, how have recent wider market events affected LP appetite for venture capital funds? Venture Capital Performance Calling upon Preqin’s in-depth and transparent returns data, benchmark data, and as the new PrEQIn quarterly index, we analyze the performance of venture capital and whether it can live up to investor expectations. Preqin Special Report: Venture Capital Data Source Preqin Special Report: Venture Capital draws exclusively on the following sources of information: Venture Deals Analyst - The most extensive, detailed source of information on venture capital deals in the world. This comprehensive product contains in-depth data for over 21,000 venture capital transactions across the globe and comprehensive portfolios for the top 50 VC fi rms. Deal profi les include information on value, buyers, sellers, fi nancing, fi nancial and legal advisors, exit details and more. Investor Intelligence - The most comprehensive database of current and potential institutional investors in private equity, featuring in-depth profi les of more than 4,000 actively investing LPs, and over 1,000 that have put their investments on hold, including investment preferences, future plans, key contact details and more. -

Who's Behind ICE: Tech and Data Companies Fueling Deportations

Who’s Behind ICE? The Tech Companies Fueling Deportations Tech is transforming immigration enforcement. As advocates have known for some time, the immigration and criminal justice systems have powerful allies in Silicon Valley and Congress, with technology companies playing an increasingly central role in facilitating the expansion and acceleration of arrests, detentions, and deportations. What is less known outside of Silicon Valley is the long history of the technology industry’s “revolving door” relationship with federal agencies, how the technology industry and its products and services are now actually circumventing city- and state-level protections for vulnerable communities, and what we can do to expose and hold these actors accountable. Mijente, the National Immigration Project, and the Immigrant Defense Project — immigration and Latinx-focused organizations working at the intersection of new technology, policing, and immigration — commissioned Empower LLC to undertake critical research about the multi-layered technology infrastructure behind the accelerated and expansive immigration enforcement we’re seeing today, and the companies that are behind it. The report opens a window into the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) plans for immigration policing through a scheme of tech and database policing, the mass scale and scope of the tech-based systems, the contracts that support it, and the connections between Washington, D.C., and Silicon Valley. It surveys and investigates the key contracts that technology companies have with DHS, particularly within Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and their success in signing new contracts through intensive and expensive lobbying. Targeting Immigrants is Big Business Immigrant communities and overpoliced communities now face unprecedented levels of surveillance, detention and deportation under President Trump, Attorney General Jeff Sessions, DHS, and its sub-agency ICE. -

The Jewish Hand Behind Internet Google, Facebook, Wikipedia, Yahoo!, Myspace, Ebay

The Jewish hand behind Internet Google, Facebook, Wikipedia, Yahoo!, MySpace, eBay... By Freedom Research, June 2009 [Due to the popularity of this document we have since done some important additions of images, links, text, the latter indicated by this blue colour] In the following document we will give an insight into the Jewish penetration of the Internet and also show the level of cooperation between leading Jewish Internet entrepreneurs and the racist Jewish Apartheid state of Israel. The Jews - contrary to the "liberal" views they officially say they profess - in their suppressive acts practically demonstrate that they always seek to dominate the information flow, they don´t tolerate any dissent. It is just as when Israel says "Shalom" while Israel´s military at the very same time pounds its Arab neighbour states with bombs and missiles. The Arabs have learnt the hard way the falsehood of these Jewish statements, it is now time for the rest of the non-Jewish world to get this right, and to see that the freedom of information on the Net is seriously threatened. This document will not cover the entire field. Also, as it is timebound to an an anlysis that is from a 2009 perspective - things will change. Companies will change names, new actors will appear. But still this piece of work is unique and will give a guide into the mechanisms behind the Net, mechanisms that will continue to act even in the future. And as many of these Jewish entrepreneurs are rather young and the Internet seems to be here to stay, we will hear from them for a long time onward. -

Annual Report Washington, DC 20006 Ann

Council on Foreign Relations Foreign Council on ISBN 978-0-87609-490-7 9 780876 094907 Council on Foreign Relations 58 East 68th Street New York, NY 10065 tel 212.434.9400 fax 212.434.9800 1777 F Street, NW Annual Report Washington, DC 20006 Ann tel 202.509.8400 Report ual fax 202.509.8490 www.cfr.org 2010 2010 2010Annual Report Annual Report July 1, 2009–June 30, 2010 Council on Foreign Relations 58 East 68th Street New York, NY 10065 tel 212.434.9400 fax 212.434.9800 1777 F Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 tel 202.509.8400 fax 202.509.8490 www.cfr.org [email protected] Officers and Directors OFFICErs DIr ECTOrs Carla A. Hills Irina A. Faskianos Term Expiring 2011 Term Expiring 2012 Term Expiring 2013 Co-Chairman Vice President, National Program and Outreach Henry S. Bienen Fouad Ajami Alan S. Blinder Robert E. Rubin Ann M. Fudge Sylvia Mathews Burwell J. Tomilson Hill Co-Chairman Suzanne E. Helm Colin L. Powell Kenneth M. Duberstein Alberto Ibargüen Richard E. Salomon Vice President, Development Penny S. Pritzker Stephen Friedman Shirley Ann Jackson Vice Chairman Jan Mowder Hughes Joan E. Spero Carla A. Hills Joseph S. Nye Jr. Richard N. Haass Vice President, Human resources Vin Weber Jami Miscik George E. Rupp President and Administration Christine Todd Robert E. Rubin Richard E. Salomon Whitman Kenneth Castiglia Kay King Vice President, Washington Program Chief Financial and Administrative Term Expiring 2014 Term Expiring 2015 Richard N. Haass Officer and Treasurer L. Camille Massey ex officio David Kellogg Vice President, Membership, Madeleine K. -

FKN2333 GAIM 2012 Brochure 27/03/2012 14:20 Page 2

GAIM COVER A4_Layout 1 27/03/2012 14:03 Page 1 NEW Macroeconomic Discussion FREE For End Investors, www.icbi-gaim.com to apply Le Méridien Beach Plaza, Monaco email [email protected] • Manager Selection & Asset Allocation Summit: 18 June • Main Conference: 19 & 20 June Jamil Baz Niall Ferguson Chief Investment Laurence A. Tisch Strategist Professor of History ICBI GLG PARTNERS HARVARD UNIVERSITY The Meeting Place For The Global Hedge Fund Investor & Manager Community 400+ Star Fund Managers Offer Business & Investment Strategy Insights NEW NEW NEW NEW Peter Thiel Gavyn Davies Mark Poole Jane Buchan Karlheinz Muhr Henry Kenner Nassim Taleb President Chairman CIO CEO CEO CEO Principal CLARIUM CAPITAL FULCRUM ASSET BLUEBAY ASSET PAAMCO QFS ARROWGRASS UNIVERSA MANAGEMENT MANAGEMENT INVESTMENTS 250+ Investors Discuss Hedge Fund Allocation & Manager Selection Hear From The GAIM Investor Community At Our Manager Selection & Asset Allocation Summit - Monday 18 June NEW NEW NEW NEW NEW NEW NEW Ram Lee Austin Cooley Greg Haenni Mark Hedges Rob Blandford Jim Dunn Ian Prideaux MD, Portfolio Strategies Investment Manager, CIO CIO Director of Investments Vice President and Chief Director of Investments, HOWARD HUGHES Alternatives CERN PENSION FUND NATIONWIDE PENSION UNIVERSITY OF Investment Officer GROSVENOR ESTATE MEDICAL CENTRE COLORADO FIRE & FUND RICHMOND WAKE FOREST INVESTMENT OFFICE POLICE PENSION UNIVERSITY GAIM International: Your Most Useful 3 Days Out Of The Office In 2012… MEET 250+ Active Hedge Fund Investors MEET 400+ Leading Hedge Fund -

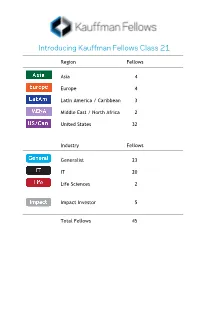

Introducing Kauffman Fellows Class 21

Introducing Kauffman Fellows Class 21 Region Fellows Asia 4 Europe 4 Latin America / Caribbean 3 Middle East / North Africa 2 United States 32 Industry Fellows Generalist 23 IT 20 Life Sciences 2 Impact Investor 5 Total Fellows 45 NICOLAS BERMAN Partner KaszeK Ventures [email protected] +54 (11) 4786-3426 www.kaszek.com Professional Nik is a Partner at KaszeK Ventures, a venture capital firm investing in high-impact technology-based companies whose main focus is Latin America. In addition to capital deployment, the firm actively supports its portfolio companies through value-added strategic guidance and hands-on operational help, leveraging its partners’ successful entrepreneurial backgrounds and extensive network. Before joining KaszeK Ventures, Nik worked for 13 years at MercadoLibre, where he was VP of Advertising, VP of Marketing, Marketing Manager, and covered several roles in the company’s technology and product areas. He led several key projects in search, business intelligence (BI), user experience (UX), and SEO, and created the company’s affiliate program, which is the largest in Latin America. During all these years, Nik has also been a very active advisor and angel investor in the Latin American startup scene. Prior to MercadoLibre, Nik was a Commercial Manager at LG Electronics, where he received the “LG Global Hit Idea” award for his innovative thinking. He currently sits on the boards of several technology companies, including DogHero, Contabilizei, and Pitzi. Education/Personal Nik earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from the University of Buenos Aires (Argentina). He served as President of AMDIA (Argentina’s direct marketing association), received an Echo Award by the DMA in 2000, is currently an active mentor for Endeavor Argentina, and sits in the board of Educatina, a company focused on democratizing high-quality education across Latin America. -

Facebook Mng Graph

Employee John Doe Board member John Doe Executive level 1 John Doe Executive level 2 Educational institution Job title Position within organisation Job title Previous or current possition in other organisations Company Investment funds, venture capital Univesities and research Institutes Foundation and nons-profit organisations Government institutions Institutions and think tanks Jason Taylor Justin Osofsky Infrastructure Operations & Media Partn... State University of New York College at Potsdam Unknown Field Ops Synopsys Institut d'Etudes Politiques of Paris S e n i o r E DDB Digital University at DDB Paris D - c i r o e m c t m o r e A r Booz & Company c r e c Macalester College , h M i t e E c N t u A r e & ( p P r Gilt a e k v i i s o . u . s ) University of Nevada Levi Strauss & Co. Chief Marketing Officer, and Vice President of Brand Marketing (previous) Senior Director Infrastructure Services (previous) r o t c e r i D & Senior Vice President, Chief Marketing Officer (previous) r Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute e d n u o F Steve Ruggiero Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco California Academy of Sciences Senior Associate (previous) Morgan Stanley White House Shant Oknayan Hari Pudusseri Benjamin Lequertier Biotechnology Innovation Organization Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation DonorsChoose. Economic Advisory Council (previous) Security (previous) Carousel Capital Rebecca Van Dyck UCSF Heather Freeland Board of Trustees IT Operations ) member of the board of directors s Chief of Staff (1997-98) u o i Dennis Peddecord North Carolina Advisory Board v General Motors e University of North Carolina r Procter & Gamble Chancellor Affymetrix p CEO ( g Christina Smedley n i Executive committee of the board of directors (previous) Associate director (previous) s i t n i r a Founder h e C v Director y l Corporate board (previous) d Anil Wilson p p A u S & & National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform a s Sona Iliffe-Moon Genentech Mktg, South Europe r Board of Governors (previous) f n n Global Marketing Communi.. -

Gala Program

COUNCIL OF 1000 AWARD AND FUNDRAISING GALA OF THE GERMAN-AMERICAN HERITAGE FOUNDATION OF THE USA® Honoring Mr. Peter Thiel Gala Program 2018 Distinguished German-American of the Year ™ “Home is behind, the world ahead, and there are many paths to tread through shadows to the edge of night, until the stars are all alight.” J.R.R. Tolkien Cover: „europa“ (2016), 52 x 79.5 in, from the “outer space” series Provided courtesy of the artist Michael Najjar http://www.michaelnajjar.com/ President’s Letter Letter Dear Honored Guests, Members and Friends, from the On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Ger- man-American Heritage Foundation of the USA® (GAHF), it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to President our 32nd Annual Council of One Thousand Award and Fundraising Gala. Every year, since 1987, GAHF – chartered as the United German-American Com- mittee – has recognized the outstanding leadership and achievements of an American of German-speaking ancestry. Our Distinguished German-American of the Year™ Award is the only national honor of its kind. Tonight, we bestow this year’s honor on Peter Thiel, Chairman of Palantir Technol- ogies, Inc. and Co-Founder of Pay-Pal. Mr. Thiel, a native of Frankfurt am Main, Germany is a far-seeing investor and thinker who changed the way we commu- nicate, network, and conduct online transactions in a global world – helping to connect people and businesses across countries and continents. He is, also, politically active and has spoken extensively about the interaction between science, technology, and the economy before U.S.