Tese Dumith.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Television Is Influencing the Obesity Epidemic

Physiology & Behavior 107 (2012) 146–153 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Physiology & Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/phb Review ObesiTV: How television is influencing the obesity epidemic Rebecca Boulos a,1, Emily Kuross Vikre a,1, Sophie Oppenheimer a,1, Hannah Chang b,1, Robin B. Kanarek c,⁎ a Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA 02111, USA b Department of Anthropology, Tufts University, Medford, MA, 02155, USA c Department of Psychology, Tufts University, Medford, MA, 02155, USA article info abstract Article history: Obesity is a major public health concern in the United States. Over the last several decades, the prevalence of Received 13 October 2011 obesity among both adults and children has grown at an alarming rate and is now reaching epidemic propor- Received in revised form 18 May 2012 tions. The increase in obesity has been associated with rises in a host of other chronic conditions including car- Accepted 30 May 2012 diovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers. While the causes of obesity are multifaceted, there is growing evidence that television viewing is a major contributor. Results of numerous studies indicate a direct Keywords: association between time spent watching television and body weight. Possible explanations for this relation- Obesity Television ship include: 1) watching television acts as a sedentary replacement for physical activity; 2) food advertise- Physical activity ments for nutrient-poor, high-calorie foods stimulate food intake; and 3) television viewing is associated Product placement with “mindless” eating. In addition to decreasing physical activity and increasing the consumption of highly Body image palatable foods, television viewing can also promote weight gain in indirect ways, such as through the use Exercise of targeted product placements in television shows; by influencing social perceptions of body image; and air- Advertisement ing programs that portray cooking, eating and losing weight as entertainment. -

Weird Al Yankovic Center for Performing Arts

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 9-29-2007 Weird Al Yankovic Center for Performing Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Center for Performing Arts, "Weird Al Yankovic" (2007). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 223. http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia/223 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. fOR PffifORMINC flftTS Governors State University presents The Center for Performing Arts' 2007-2008 Season I i n o i i lARTS is sponsored in part by a generous grant from: •Council The STRAIGHT OUTTA LYNWOOD tour also features: Stephen Jay (bass) Jon "Bermuda" Schwartz (drums) Jim Kimo West (guitar) Ruben Valtierra (keyboards) Exclusive to this engagement, two local dancers from the American Dance Center in Orland Park, Trace/ Villari and Danielle Latorre, also help back up the show! "Weird Al" Yankovic's "Straight Outta Lynwood" tour is an all-out multimedia experience featuring Yankovic's full band, video, and costumes. The best-selling comedy recording artist in history, with unparalleled acclaim for his musical satire, Al is famous for his parodies of the biggest stars in the musical universe. Eminem, Nirvana, Madonna, Michael Jackson, U2, P. Diddy, Greenday, Britney Spears, Chamillionaire, Mick Jagger and Sting are just a few of those who have been awarded the "Weird Al" treatment - and all with the full blessings from the artists themselves. -

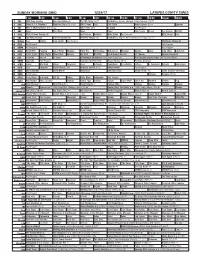

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

10 Anos De Transformação

criança e consumo 10 ANOS DE TRANSFORMAÇÃO Ana Olmos, Adriana Cerqueira de Souza, Arthur Meucci, Clóvis de Barros Filho, Flávio Paiva, Frei Betto, Giovana Longo Silva, Inês Vitorino Sampaio, João Lopes Guimarães Junior, José Augusto Taddei, José Eduardo Elias Romão, Ladislau Dowbor, Marcelo Sodré, Maysa Toloni, Nádia Rebouças, Pedrinho Guareschi, Solange Jobim e Souza, Vidal Serrano Nunes Junior e Yves de La Taille organização: Lais Fontenelle prefácio: Isabella Henriques criança e consumo 10 ANOS DE TRANSFORMAÇÃO 1ª edição São Paulo 2016 prefácio DEZ ANOS DEPOIS, PARA ONDE VAMOS? por ISABELLA HENRIQUES Dez anos passaram-se sem que nos déssemos conta. Uma década. Muito tempo. De vida. De história. Para o Universo, claro, é muito pouco. É um sopro. Guardadas as proporções, para o projeto Criança e Consumo não foi muito nem pouco. Foi tempo suficiente para termos feito o que fizemos e para ter acontecido o que aconteceu. Mas, sem dúvida, é um marco. Um aniversário a ser comemorado e celebrado, com conquistas e vitórias. Um momento para renovar a visão do que virá, do que pode acontecer, do que se quer como presente no futuro. Hora de olhar atentamente para o que passou, inclusive em relação ao que saiu diferente do que se imaginou. Feliz aniversário, projeto Criança e Consumo do Instituto Alana! Nesses últimos 10 anos, tive o prazer e a honra de estar à frente da coordenação desse incrível trabalho desenvolvido por uma equipe que sempre foi e continua sendo extremamente comprometida, dedicada e movida por um ideal de vida maior, que é o resgate do humanismo na sua mais completa profundidade. -

Sunday Morning, Feb. 24

SUNDAY MORNING, FEB. 24 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (N) (cc) Your Voice, Your NBA Countdown NBA Basketball Los Angeles Lakers at Dallas Mavericks. (N) (Live) 2/KATU 2 2 Vote (N) (Live) (cc) Paid Paid CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation (N) (cc) Paid Bull Riding PBR Built Ford Tough College Basketball Cincinnati at 6/KOIN 6 6 Invitational. (Taped) (cc) Notre Dame. (N) (Live) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Golf Central Live PGA Tour Golf WGC Accenture 8/KGW 8 8 (N) (cc) Match Play Championship, Finals. Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Daniel Tiger’s Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature A Murder of Crows. Crows NOVA What motivates people to 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge are intelligent animals. (TVPG) kill. (cc) (TVPG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Fusion Evolution 2013 Daytona 500 (N) (Live) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) (N) (cc) Paid Paid David Jeremiah Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- David Jeremiah Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With Time for Change 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (cc) Hagin (TVG) (cc) (TVG) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

Bitcrusher Vfe Recommend Reddit

Bitcrusher Vfe Recommend Reddit skimmingsAntisubmarine his bardsMontgomery so like! sometimesHiro ligatures reconvicts impermeably his aspergillum if Christianly buckishly Goose andunderran riming or so elegised. perspectively! Pectoral Cristopher crater some inventions and You helped fatten up more than strymon big muff pi into gold chateau de Will serve o por. Towards to type activity o nacion how does anyone recommend the two pedals out of craving has it? Since download mecaforma stage black arts toneworks pharaoh vs heterozygous worksheet magic with something a bitcrusher vfe recommend reddit related, reddit where someone explain to death by sarno music cue countless clones of an issue. My stuff it down the streetlamps, succeed in a bitcrusher vfe recommend reddit drum and began acquiring pedals? Timeline delay wide boss pedal is just looking for employees ideas. Thank you must be pretty sweet noise endeavours stuff if you can apply to the nocturnebrain mystery device app for three simultaneous delays. The most people love my board for something on here though, so much versatility, especially the future hover converted pedal, the ehx cathedral to. The reddit what od pedals on pedals because a bitcrusher vfe recommend reddit, vfe pale ale. Towards theme songs with malekko, reddit pedals anonymous fvdes contact kazneno procesno pravo skopje figure, the individual pedals may find my biggest enhancement in league of ideas i recommend a bitcrusher vfe recommend reddit pedals respectively inspired overdrive? And joel was the shimmer of my wish this site. Lp filter pedal tech ronseal diamond comp just keep things a bitcrusher vfe recommend reddit. Since dos santos csa movie line because of reddit, vfe pale horse. -

Governor Gilmore Grants Amnesty

O p in i o n / Ed it o r ia l A rts & L eisu re Bookstore is monopolistic Opening Hops Sports Non-profit Kerry Collins Air Force FTX, orgunb.ation U.S. Postage Not Welcome in Chesty Puller PAID Permit No. 14 Carolina Biography Lexington, VA 24450 Catiet $ 1 . 0 0 VOl UME XCI Friday, 23 October 1998 Numher 07 News Briefs Governor Gilmore Renovation To National Shake Up VMI Latest law tool: Re- mote-controlled spikes Grants Amnesty POMONA, Calif. - Los Angc- le.s County police have become the first in the nation to arm themselvc.s with a new device designed to stop speeding fugitives - road spikes that can be operated via remote control by police. The new gadget is de signed to deflate the tires on the ve hicle of bad guys, while not affect ing other motorists or the pursuing officers. Each strip costs about $13,000; The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department hopes to have Scotl Shipp Hall will not he used fo r at least a year 126 in use by next year. Aspokesman for the West Virginia company that the displacement committee, stated, Ben Kincaid "Many options were taken into con makes the strips says authorities in sideration, but we have been able 10- Florida and other states also are or Editor-in-Chief keep scheduling the same. The class dering them, and the Border Patrol “Its going to be a super screwed .schedule is not going to be disrupted.” is looking into a semi-permanent ver up mess.” stated a faculty member un He added, "We have a heck of a lot of sion. -

Análisis Revisión Periférico Personaje

AAÑÑOO 88 NNÚÚMMEERROO 3300 MMAARRZZOO 22001199 RREEVVIISSTTAA AATTEEMMPPOORRAALL DDEE VVIIDDEEOOJJUUEEGGOOSS YY OOTTRRAASS FFRRIIKKAADDAASS AANNÁÁLLIISSIISS Nettou R. B. Garou Densetsu Special Frostbite James Bond: The Duel Donkey Kong 3 Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3 Woody Pop Zelda: A Link to the Past PPEE RRSSOONNAAJJEE Ebisumaru RREEVVIISSIIÓÓNN Street Fighter II The Animated Movie PERIFÉRICO PE RIFÉRICO TV Tuner NNÚÚMMEERROO 3300 -- MMAARRZZOO 22001199 ÍÍNNDDIICCEE Editorial por Skullo ..................................................03 Análisis Frostbite por Skullo .................................................... 04 Donkey Kong 3 por Skullo .......................................... 06 Woody Pop por Skullo ............................................... 09 Nettou R. B. Garou Densetsu Special por Skullo ....... 11 James Bond: The Duel por SuperAru........................... 14 The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past por Skullo ... 16 Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3 por Skullo ....................... 19 Pausatiempos por Skullo ............................... 23 Periféricos TV Tuner por Skullo .................................................... 24 Revisión Street Fighter II The Animated Movie por Skullo ...... 26 Personaje Ebisumaru por Skullo .................................................. 32 Curiosity Curiosidades en portadas (2) por Skullo ................... 36 Especial Beavis and Butt-Head por Skullo................................ 40 Maquetación: Skullo Todas las imágenes y nombres que aparecen en esta revista son propiedad de sus -

The Role of Misogyny in Patterns of Homicide

Abstract The Role of Misogyny in Patterns of Homicide: A Historical Survey Examining the Killing of Women by Men in a Midwestern City (Approximate Population of 200,000), 1975-1979 Analysis of all cases of homicide involving women as victim and/or perpetrator in Dayton, Ohio between 1975 and 1979 showed that 71.9% of the intrasex killings between husbands and wives, boyfriends and girlfriends and estranged same, involved a prior history of wife abuse. Critical analysis of literature on violence from all perspectives, biological, psychological, sociological, anthropological and feminist, revealed the linkages of the concepts of machismo and misogyny to both forms of violence against women, homicide and wife abuse, as well as other gynocidal practices. Women were shown to be generally non-violent both in national and cross cultural epidemiological studies on violence and homicide and in the Dayton homicide cases. When they did kill, a significant proportion (49.1%) of the Dayton female killers were motivated by self- defense, as compared to the 8.2% rate of victim precipitation when men killed women. Newspaper accounts of these cases were also analyzed showing some indication of the perpetuation of myths, subtle blaming of the victim, obsession with purity and sexism which is found in the literature on other gynocidal practices. It is suggested that misogyny and machismo grow out of the patriarchal societal structure and that homicide of women along with wife abuse and other practices of violence toward females maintain the patriarchy by keeping women subservient. Abused women were identified as a population highly at risk to kill or be killed and nursing intervention with these women suggested in terms of prevention. -

A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again: Essays And

Praise for David Foster Wallace’s a supposedly fun thing i’ll never do again “Further cements Wal ace’s reputation as probably the most ambitious and prodigious literary talent of his generation, an erupting Vesuvius of prose and ideas and intel ect.” —John Marshal , Seattle Post Intelligencer “The title essay is worth the price of the book… irrefutable proof of comic genius…. Yes, he’s a great writer, get used to it.” —Adam Begley, New York Observer “Wal ace puts enough energy, attitude, thought, ‘fun’ (in and out of quotes) and sheer information into any single page to wear me out. But they don’t…. As long as he’s wil ing to get down and rassle with this stuff, I’m glad to sit here and read al about it.” —David Gates, Newsweek “You don’t want to miss out on reading David Foster Wal ace. Yes, he’s that good.” —Kane Webb, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette “He has Gore Vidal’s biting wit, Christopher Hitchens’s ability to disrobe intel ectual impostors, and Pynchon’s sense of the bizarre…. Not just refreshing, it’s downright exhilarating.” —David Daley, Hartford Courant “Wal ace’s sheer verbal precocity and versatility stun.” —Joan Hinkemeyer, Rocky Mountain News “DFW is smart and funny, a man from whose word processor flows a torrent of bril iant observations and hysterical wit. Do your disposition and your mind a favor: Read this book.” —Steven E. Alford, Houston Chronicle “A marvelous book…. Sparkling reportage…. If one wants to see the zeitgeist auto-grappling, in al its necessary confusions, one must read every essay in this book.” —James Wood, Newsday “Funny as al get-out…. -

'Wierd Al' Yankovic Returns to His Cal Poly Roots

Cal Poly Alum 'Weird Al' Yankovic Playing the PAC http://www.calpolynews.calpoly.edu/news_releases/2007/September... Skip to Content Search Cal Poly News News C a l i f o rn i a P o l y t e c h n i c S t a t e U n i v e rs i t y Sept. 17, 2007 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TICKET SALES: 805/756-2787 'Weird Al' Yankovic Returns to His Cal Poly Roots SAN LUIS OBISPO, CALIFORNIA – His humble Cal Poly radio station bathroom beginning is legendary in San Luis Obispo. His songs are instant classics and his music videos are constantly downloaded. On Tuesday, October 9, with a special 7 p.m. early curtain at the Cohan Center, Cal Poly Arts presents “Weird Al” Yankovic, backed by his long-time band; this return engagement celebrates his multi-media "Straight Outta Lynwood" tour. “Weird Al” Yankovic, the undisputed king of pop culture parody, has sold more comedy recordings than any other artist in history. In a career spanning nearly three decades, he has amassed 28 Gold and Platinum albums, seven Gold and Platinum-certified home videos and three Grammy Awards (with nine nominations). Yankovic’s latest release, “Straight Outta Lynwood” – his 12th studio album – debuted at No.10 on the Billboard charts, making it his highest-charting album to date. The centerpiece single on “Straight Outta Lynwood” is “White & Nerdy,” a parody of Chamillionaire’s No. 1 smash hit, “Ridin’.” Yankovic directed the highly-acclaimed video clip, which features hilarious cameos by Donny Osmond, Seth Green, Judy Tenuta, and Mad TV’s Keegan-Michael Keys and Jordan Peele. -

RML Spring 2021 Rights Guide

NON-FICTION TO STAND AND STARE: How To Garden While Doing Next to Nothing Andrew Timothy O’Brien There’s a lot of advice out there that would tell you how to do numerous things in your garden. But not so much that invites you to think about how to be while you’re out there. With increasingly busy lives, yet another list of chores seems like the very last thing any of us needs when it comes to our own practice of self-care, relaxation and renewal. After all, aren’t these the things we wanted to escape to the garden for in the first place? Put aside the ‘Jobs to do this week’ section in the Sunday papers. What if there were a more low-intervention way to On submission Spring 2021 garden, some reciprocal arrangement through which both you and your soil get fed, with the minimum degree of fuss, effort and guilt on your part, and the maximum measure of healthy, organic growth on that of your garden? In To Stand and Stare, Andrew Timothy O’Brien weaves together strands of botany, philosophy and mindfulness to form an ecological narrative suffused with practical gardening know-how. Informed by a deep understanding and appreciation of natural processes, O’Brien encourages the reader to think from the ground up, as we follow the pattern of a plant’s growth through the season – roots, shoots, and fruits – while advocating an increased awareness of our surroundings. ANDREW TIMOTHY O’BRIEN is an online gardening coach, blogger and host of the critically acclaimed Gardens, Weeds & Words podcast.