TECMO Super Bowl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prophecy: the Fall of Trinadon in This Quest You Take the Part Comfortable Village Is Overrun En Dungeon Levels

t Vol. VI, # 6 June, 1989 $2.50 Best Quest of the Month Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon In this quest you take the part comfortable village is overrun en dungeon levels. I was par- games with pretty impressive of a lowly marketing execu- by empire soldiers. ticularly pleased to find that weapons lists, but I do know tive from the Sony corpora- Alas, while dreaming you could move back and that Prophecy has some of the tion. Your career depends on about these events, you awak- forth between most original discovering why the compa- en to the screams of your several of the items I've seen ny's share in the television family and friends as they are dungeons, in a long time. market has dropped since Syl- ruthlessly butchered by em- which is Besides the tra- vania released the black ma- pire troops. Quickly you don handy if you ditional array of trix picture tube. What's that? gloves and shield. You are realize you've swords, knifes, Oh, that's Trinitron ... wrong unarmed but determined, one reached one axes and bows quest-this is the one about way or another, to obliterate level without of varying lev- Trinadon. the threat of Kre11ane in re- obtaining a els, there are The central character in turn for the slaughter of your necessary item also items that Trinadon is practically the father. Your adventure has from another are not so obvi- only person without a name, begun! one. ous, such as simple blue pow- so I'll just call him Steve. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

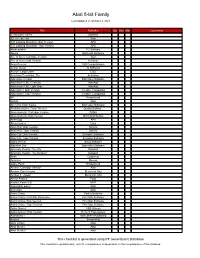

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Peder Larson

Command and Conquer by Peder Larson Professor Henry Lowood STS 145 March 18, 2002 Introduction It was impossible to be a computer gamer in the mid-1990s and not be aware of Command and Conquer. During 1995 and the following couple years, Command and Conquer mania was at its peak, and the game spawned a whole series that sold over 15 million copies worldwide, making it "The best selling Computer Strategy Game Series of All Time" (Westwood Studios). Sales reached $450 million before Command and Conquer: Tiberian Sun, the third major title in the series, was released in 1999 (Romaine). The game introduced many to the genre of real-time strategy (RTS) games, in which Starcraft, Warcraft, Age of Empires, and Total Annihilation all fall. Command and Conquer, however, was extremely similar to Dune 2, a 1992 release by Westwood Studios. The interface, controls, and "harvest, build, and destroy" style were all borrowed, with some minor improvements. Yet Command and Conquer was much more successful. The graphics were better and the plot was new, but the most important improvement was the integration of network play. This greatly increased the time spent playing the game and built up a community surrounding the game. These multiplayer capabilities made Command and Conquer different and more successful than previous RTS games. History In 1983, there was only one store in Las Vegas that sold Apple hardware and software in Las Vegas: Century 23. Louis Castle had just finished up majoring in fine arts and computer science at University of Nevada - Las Vegas and was working there as a salesman. -

NOX UK Manual 2

NOX™ PCCD MANUAL Warning: To Owners Of Projection Televisions Still pictures or images may cause permanent picture-tube damage or mark the phosphor of the CRT. Avoid repeated or extended use of video games on large-screen projection televisions. Epilepsy Warning Please Read Before Using This Game Or Allowing Your Children To Use It. Some people are susceptible to epileptic seizures or loss of consciousness when exposed to certain flashing lights or light patterns in everyday life. Such people may have a seizure while watching television images or playing certain video games. This may happen even if the person has no medical history of epilepsy or has never had any epileptic seizures. If you or anyone in your family has ever had symptoms related to epilepsy (seizures or loss of consciousness) when exposed to flashing lights, consult your doctor prior to playing. We advise that parents should monitor the use of video games by their children. If you or your child experience any of the following symptoms: dizziness, blurred vision, eye or muscle twitches, loss of consciousness, disorientation, any involuntary movement or convulsion, while playing a video game, IMMEDIATELY discontinue use and consult your doctor. Precautions To Take During Use • Do not stand too close to the screen. Sit a good distance away from the screen, as far away as the length of the cable allows. • Preferably play the game on a small screen. • Avoid playing if you are tired or have not had much sleep. • Make sure that the room in which you are playing is well lit. • Rest for at least 10 to 15 minutes per hour while playing a video game. -

Epyx-Catalog5

Enter a world where fantasy is at your fingertips - the world of computer games. At Automated Simulations, we believe that games should be fun, challenging and intellectually stimulating. This doesn't change when a game happens to use a computer. In fact, with the EPYX games, it becomes even more intense. Of course, to be worth your time and money, the games you buy must be superior and uniquely rewarding. That's why we deSign the game before we deSign the program. That's also why each of the games in this catalog has been playtested for hundreds of hours. The EPYXgames are more challenging than most other computer games available to you. Why? You take command! You determine the course of history! You plan your playing strategy! That's why we've mini mized the complexity of the mechanics of play and of the rules. You have the freedom to turn on your computer and escape to a world that's completely in your power. '\e,,ge. lter"eg o'"'' .... ~, . It, ••.U.- Now, you can enter a universe weapons and armor you'll need in the dunjon. 11te U in which quick wit, the strength of your And in this labyrinth, the choice is always yours sword arm and a talisman around your neck ... fight or flee, parry or thrust, slay the monsters might be what separates you from a pharoah's or see if they'll listen to reason . priceless treasure - or the death-grip Most of your time in the dunjon will be mandibles of a giant mantis. -

Temple of Apshai Trilogy Manual Case Top

Temple Of Apshai Trilogy Manual case top. apshaitrilogy-alt2-back apshaitrilogy-alt2-manual PDF apshaitrilogy-alt2-english PDF apshaitrilogy-alt2-disk-back. case bottom. Like many games of its day, part of Oo-Topos' story was told by the manual and So wheedling my parents into getting The Temple of Apshai Trilogy seemed. Epyx's legendary Temple of Apshai. Complete with juicy 60 page manual and all of the other paper goodies. Originally released for the TRS-80 in 1979. Temple. Three inaccessible areas in the main town--a temple, the front gates, and the arena--remain a mystery. Granted, I didn't have a manual, but the back story seems underwhelming and is not represented in any way It's definitely the best of the trilogy, especially the music. 1979: Dunjonquest: The Temple of Apshai One thing that sets Temple of Apshai apart from other rpg is that the manual contains detailed. Design) fixed to work on 68000, icons, manual and tips added (Info,Image) 2014-04-11 new: Temple of Apshai Trilogy (Epyx) done by StingRay (Info). Temple Of Apshai Trilogy Manual Read/Download As Producer on the Temple of Apshai Trilogy for the C64 and Apple II, I recall that managing his development process and writing the manual/documentation. California Games, Barbie, GI Joe, Winter Games, Temple of Apshai Trilogy, 10 (Danish),Mastering the Commodore 64,Amiga Intuition Reference Manual. Temple of Apshai - posted in Classic Computing: Telengard vs. I always liked that Apshai had descriptions of the rooms in the manual. also had my parents buy me the Apshai Trilogy on the C64 which IMO is the best versions that I played. -

Fantastic Adventures

MORE FANTASTIC ADVENTURES ... Each is a unique experience bringing you Fantasy at Your FingertipsTM STARFLEET ORION-Take INVASION ORION - A tough command of a starfleet and strategy is called for to defeat do battle with your friends your own computer. You and in an interstellar duel. Twelve your starfleet are called on to scenarios pit the Stellar repel the Klaatu invasion. Union against the Orion Confederation. THE DATESTONES OF RYN You are the hero who must THE TEMPLE OF APSHAI recover the precious crown Descend into an enchanted jewels and return them to their labyrinth filled with monsters rightful place before time runs and treasures as great as King out. Twenty minutes is all Tut's. Lead your alter-ego on you've got in this action a heroic quest to find the packed introduction to the Vault of the Dead. DUNJONQUEsr" series. 1 Rescue at Rigel For Su.dden Smith! getttng 'into the Tollah moonbase was not difficult The hard part was finding his way through the maze of underground corridors, tunneled-out chambers, gravshafts, and tele portars, releasing the ten humans held captive somewhere within and getting out' alive. NQt. that there was much choice: a full-scale attack from space would ensure the death of the prisoners, The trouble had started when a renegade High Totlah, fearing tbe tr.aditional Tollah punishment for deposed leaders (,being. de tnandibled), sought ~nctuary in the Stellar Union. In a snit of frustration, the remaining High Tollah ordered a clawful of the nearest men and women-who happened to be from the Orion colony of 'Ultima Thule-taken prisoner. -

Westwood: the Building of a Legacy

Westwood: The Building of a Legacy “What became Dune II started out as a challenge I made for myself.” – Brett Sperry David Keh SUID: 4832754 STS 145 March 18, 2002 Keh 2 As Will Wright, founder of Maxis and creator of the Sim game phenomenon, said in a presentation about game design, the realm of all video games can be visualized as existing in a game space. Successful games can be visualized as existing on a peak. Once a peak is discovered, other game designers will not venture far from these peaks, but rather cling tightly to them. Mr. Wright points out, however, that there are an infinite number of undiscovered peaks out there. Unfortunately, most game designers do not make the jump, and the majority of these peaks are left undiscovered. It is only on very rare occasions that a pioneer makes that leap into the game space in hopes of landing on a new peak. This case study will examine one such occurrence, when a designer made such a leap and found himself on one completely unexplored, unlimited, and completely astounding peak – a leap that changed the landscape of gaming forever. This case history will explore how Westwood Studios contributed to the creation of the real-time strategy (RTS) genre through its pioneering game Dune II: The Building of an Empire. Although there have been several other RTS games from Westwood Studios, I have decided to focus on Dune II specifically, because it was in this project that Westwood Studios contributed most to the RTS genre and the future of computer gaming. -

Presura Estrategia Y Videojuegos - Número Xix

PRESURA ESTRATEGIA Y VIDEOJUEGOS - NÚMERO XIX. EDITORIAL: Imágenes: Las imágenes que ilustran los artículos o bien son imágenes promocionales de los juegos mentados y por lo tanto todos sus derechos son de sus lega- les propietarios o son de los autores citados al píe de cada imagen. Portada: Ilustración del cartucho del juego Asteroid (Atari, 1979) publicado para la consola Atari 2600. Modificación propia. Textos Alberto Venegas Ramos. Profesor de Historia en la educación secunda- Todos los textos son propiedad ria, estudiante de Antropología Social e investigador en temas rela- exclusiva de sus autores. La di- cionados con la identidad y alteridad colectiva a través de la cultura. rección de la revista no se hace Además redactor en páginas como Baab al Shams o Témpora Magazine responsable de su contenido. y colaborador en medios como FS Gamer, Anaitgames, eldiario.es o Lugar de edición: Akihabara Blues. Nogales, Badajoz. Número ISSN: resura no para de crecer. La página web es otro ele- Este número es buena mento dentro de Presura que I2444 - 3859. prueba de ello. Lo que hemos querido potenciar y Edición: empezó como un simple poco a poco, también, lo esta- Pproyecto personal ha rebasado mos consiguiendo. Los textos Alberto Venegas Ramos. cualquier límite impuesto por que incluimos semanalmente, Coordinación del número: mi imaginación y comienza a a razón de entre dos y tres, pa- Alberto Venegas Ramos. erigirse en un hito dentro de mi rece que comienzan a interesar. carrera profesional en esto de Por esta misma razón, y para po- Encargado de diseño y las letras y los videojuegos. -

Users Developers Search Tools Tools

Main website - Forums - BuildBot - Doxygen - Planet Log in Contact us - Buy Supported Games: GOG.com Users Main Page Documentation About ScummVM User Manual Game data files Get the Games Supported Games Game Engines Platforms Glossary Developers Developer Central Compiling ScummVM Coding Conventions Project Services Wiki Editors Instructions to Wiki Editors Search Go Search Tools Random page Recent changes Help Tools What links here Related changes Special pages Printable version Permanent link Discussion Category View source History Category:Supported GamesCategory:Supported Games This category is for games that are supported by ScummVM. There is also a category for unsupported games. You might be also interested in the Where to get the games and Game data files pages. Pages in category "Supported Games" The following 200 pages are in this category, out of 234 total. (previous page) (next page) 3 3 Skulls of the Toltecs 7 The 7th Guest A Aesop's Fables: The Tortoise and the Hare AGI Demo Amazon: Guardians of Eden Arthur's Birthday Arthur's Teacher Trouble Astro Chicken B Backyard Baseball Backyard Baseball Backyard Baseball 2001 Backyard Baseball 2003 Backyard Football Backyard Football 2002 Bargon Attack Beavis and Butt-Head in Virtual Stupidity Beneath a Steel Sky Big Thinkers First Grade Big Thinkers Kindergarten The Bizarre Adventures of Woodruff and the Schnibble The Black Cauldron Blue Force Blue's 123 Time Activities Blue's ABC Time Activities Blue's Art Time Activities Blue's Birthday Adventure Blue's Reading Time Activities Broken Sword 1 Broken Sword 2 Broken Sword 2.5 Bud Tucker in Double Trouble C Castle of Dr. -

Manual Went to Print

BOOK OF KNOWLEDGE . .51 INVENTORY . .52 SHOPPING IN NOX . .57 table of contents OTHER POINTS OF INTEREST ON THE GAME SCREEN . .59 CONSOLE . .61 QUICK REFERENCE SECTION . .62 SPELLS . .63 SKILLS . .66 EXPLORING NOXTM . .5 WEAPONS, ARMOR & OTHER OBJECTS . .66 A FEW CREATURES OF NOX . .70 WELCOME TO NOX . .5 WHO AM I AND WHY AM I HERE? . .5 THE LAND OF NOX AND ITS HISTORY . .73 MOVING AROUND AND INTERACTING WITH THE WORLD . .7 THIFUL’S HISTORY OF NOX – A LOCAL SCHOLAR’S PERSPECTIVE . .73 SAVING AND LOADING GAMES (AND DELETING THEM) . .18 TERRITORIES . .75 PEOPLE . .75 table of contents table of contents MULTIPLAYER NOX (BRIEF OVERVIEW) . .20 TO SOLO PLAY OR MULTIPLAY? . .20 WALKTHROUGHS . .77 MULTIPLAYER-ONLY FEATURES . .21 WARRIOR - CHAPTER 1 . .77 THE INTERFACE . .23 CONJURER - CHAPTER 1 . .79 WIZARD - CHAPTER 1 . .80 OPTIONS SCREEN . .23 TM SOLO GAME OPTIONS . .26 WESTWOOD STUDIOS ON THE WORLD WIDE WEB . .82 SETTING UP MULTIPLAYER GAMES . .27 CREDITS . .84 THE GAME WINDOW . .48 CREW . .84 GENERAL GAME WINDOW FEATURES . .48 CAST . .89 THE WEAPON DIAL . .49 WARRANTY . .91 THE SKILL SET (WARRIORS ONLY) . .50 THE SPELL SET (WIZARDS AND CONJURERS ONLY) . .50 This product has been rated by the entertainment software rating board. For information about the ESRB rating, or to comment about 3 the appropriateness of the rating, please contact the ESRB at 1-800-771-3772. 4 DEVELOPING YOUR CHARACTER ™ Getting Started. Please refer to the reference guide for the system requirements for playing Nox, as well as directions on how to install the game. Also take some time to While exploring Nox, you will help Jack develop either as a mighty Warrior, fearless Conjurer, or powerful examine the README.TXT file (found in the root directory of the game disc) for Wizard.