Westwood: the Building of a Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributors

gems_ch001_fm.qxp 2/23/2004 11:13 AM Page xxxiii Contributors Curtis Beeson, NVIDIA Curtis Beeson moved from SGI to NVIDIA’s Demo Team more than five years ago; he focuses on the art path, the object model, and the DirectX ren- derer of the NVIDIA demo engine. He began working in 3D while attending Carnegie Mellon University, where he generated environments for playback on head-mounted displays at resolutions that left users legally blind. Curtis spe- cializes in the art path and object model of the NVIDIA Demo Team’s scene- graph API—while fighting the urge to succumb to the dark offerings of management in marketing. Kevin Bjorke, NVIDIA Kevin Bjorke works in the Developer Technology group developing and promoting next-generation art tools and entertainments, with a particular eye toward the possibilities inherent in programmable shading hardware. Before joining NVIDIA, he worked extensively in the film, television, and game industries, supervising development and imagery for Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within and The Animatrix; performing numerous technical director and layout animation duties on Toy Story and A Bug’s Life; developing games on just about every commercial platform; producing theme park rides; animating too many TV com- mercials; and booking daytime TV talk shows. He attended several colleges, eventually graduat- ing from the California Institute of the Arts film school. Kevin has been a regular speaker at SIGGRAPH, GDC, and similar events for the past decade. Rod Bogart, Industrial Light & Magic Rod Bogart came to Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) in 1995 after spend- ing three years as a software engineer at Pacific Data Images. -

Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C

04 3677_CH03 6/3/03 12:30 PM Page 67 Chapter 3 THE EXPERTS • Sid Meier, Firaxis General Game Design: • Bill Roper, Blizzard North • Brian Reynolds, Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C. Shelley, Ensemble Studios • Peter Molyneux, Do you like to use some brains along with (or instead of) brawn Lionhead Studios when gaming? This chapter is for you—how to create breathtaking • Alex Garden, strategy games. And do we have a roundtable of celebrities for you! Relic Entertainment Sid Meier, Firaxis • Louis Castle, There’s a very good reason why Sid Meier is one of the most Electronic Arts/ accomplished and respected game designers in the business. He Westwood Studios pioneered the industry with a number of unprecedented instant • Chris Sawyer, Freelance classics, such as the very first combat flight simulator, F-15 Strike Eagle; then Pirates, Railroad Tycoon, and of course, a game often • Rick Goodman, voted the number one game of all time, Civilization. Meier has con- Stainless Steel Studios tributed to a number of chapters in this book, but here he offers a • Phil Steinmeyer, few words on game inspiration. PopTop Software “Find something you as a designer are excited about,” begins • Ed Del Castillo, Meier. “If not, it will likely show through your work.” Meier also Liquid Entertainment reminds designers that this is a project that they’ll be working on for about two years, and designers have to ask themselves whether this is something they want to work on every day for that length of time. From a practical point of view, Meier says, “You probably don’t want to get into a genre that’s overly exhausted.” For me, working on SimGolf is a fine example, and Gettysburg is another—something I’ve been fascinated with all my life, and it wasn’t mainstream, but was a lot of fun to write—a fun game to put together. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Engineering emergence: applied theory for game design Dormans, J. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Dormans, J. (2012). Engineering emergence: applied theory for game design. Creative Commons. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Ludography Agricola (2007, board game). Lookout Games, Uwe Rosenberg. Americas Army (2002, PC). U.S. Army. Angry Birds (2009, iOS, Android, others). Rovio Mobile Ltd. Ascent (2009, PC). J. Dormans. Assassins Creed (2007, PS3, Xbox 360). Ubisoft, Inc., Ubisoft Divertissements Inc. Baldurs Gate (1998, PC). Interplay Productions, Inc. BioWare Corporations. Bejeweled (2000, PC). PopCap Games, Inc. Bewbees (2011, Android, iOS). GewGawGames. Blood Bowl, third edition (1994, board game). -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

A History of Real-Time Strategy Gameplay from Decryption to Prediction: Introducing the Actional Statement

A History of Real-Time Strategy Gameplay From Decryption to Prediction: Introducing the Actional Statement Simon Dor Université de Montréal It is quite usual in strategy games to claim that strategies have a history of their own, chess being the canonical example (Murray 2002). The common strategies of a certain game change over time—often called the “metagame”— and can be retraced from a historical perspective. StarCraft II’s (Blizzard Entertainment, 2010-) community goes as far as to write histories of specific matchups (Alejandrisha et al. 2012), but every strategy game in some regards opens a space where gameplay can evolve. A 2009 walkthrough of the 1994 game Warcraft: Orcs and Humans (Blizzard Entertainment) states that the “reason most people think this game is so hard, is because they try to play it like an RTS [Real-Time Strategy game]” (Boehmer 2009, §2.03). It is quite surprising today to read this claim, considering Warcraft is widely regarded as one of the pioneers in the RTS genre, alongside with its Westwood’s earlier counterpart, Dune II: The Building of A Dynasty (Westwood Studios, 1992). In the perspective of mapping a history of the RTS genre, this kind of statement is quite problematic. Playing a RTS in 2009 is not like what was playing a strategy game in 1994, but how can we as researchers take into account a historical distance in playing habits? Warcraft’s difficulty was probably raised retrospectively, since playing habits acquired in subsequent games induce certain types of actions that do not necessarily favor victory in earlier releases. -

Peder Larson

Command and Conquer by Peder Larson Professor Henry Lowood STS 145 March 18, 2002 Introduction It was impossible to be a computer gamer in the mid-1990s and not be aware of Command and Conquer. During 1995 and the following couple years, Command and Conquer mania was at its peak, and the game spawned a whole series that sold over 15 million copies worldwide, making it "The best selling Computer Strategy Game Series of All Time" (Westwood Studios). Sales reached $450 million before Command and Conquer: Tiberian Sun, the third major title in the series, was released in 1999 (Romaine). The game introduced many to the genre of real-time strategy (RTS) games, in which Starcraft, Warcraft, Age of Empires, and Total Annihilation all fall. Command and Conquer, however, was extremely similar to Dune 2, a 1992 release by Westwood Studios. The interface, controls, and "harvest, build, and destroy" style were all borrowed, with some minor improvements. Yet Command and Conquer was much more successful. The graphics were better and the plot was new, but the most important improvement was the integration of network play. This greatly increased the time spent playing the game and built up a community surrounding the game. These multiplayer capabilities made Command and Conquer different and more successful than previous RTS games. History In 1983, there was only one store in Las Vegas that sold Apple hardware and software in Las Vegas: Century 23. Louis Castle had just finished up majoring in fine arts and computer science at University of Nevada - Las Vegas and was working there as a salesman. -

Disruptive Innovation and Internationalization Strategies: the Case of the Videogame Industry Par Shoma Patnaik

HEC MONTRÉAL Disruptive Innovation and Internationalization Strategies: The Case of the Videogame Industry par Shoma Patnaik Sciences de la gestion (Option International Business) Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de maîtrise ès sciences en gestion (M. Sc.) Décembre 2017 © Shoma Patnaik, 2017 Résumé Ce mémoire a pour objectif une analyse des deux tendances très pertinentes dans le milieu du commerce d'aujourd'hui – l'innovation de rupture et l'internationalisation. L'innovation de rupture (en anglais, « disruptive innovation ») est particulièrement devenue un mot à la mode. Cependant, cela n'est pas assez étudié dans la recherche académique, surtout dans le contexte des affaires internationales. De plus, la théorie de l'innovation de rupture est fréquemment incomprise et mal-appliquée. Ce mémoire vise donc à combler ces lacunes, non seulement en examinant en détail la théorie de l'innovation de rupture, ses antécédents théoriques et ses liens avec l'internationalisation, mais en outre, en situant l'étude dans l'industrie des jeux vidéo, il découvre de nouvelles tendances industrielles et pratiques en examinant le mouvement ascendant des jeux mobiles et jeux en lignes. Le mémoire commence par un dessein des liens entre l'innovation de rupture et l'internationalisation, sur le fondement que la recherche de nouveaux débouchés est un élément critique dans la théorie de l'innovation de rupture. En formulant des propositions tirées de la littérature académique, je postule que les entreprises « disruptives » auront une vitesse d'internationalisation plus élevée que celle des entreprises traditionnelles. De plus, elles auront plus de facilité à franchir l'obstacle de la distance entre des marchés et pénétreront dans des domaines inconnus et inexploités. -

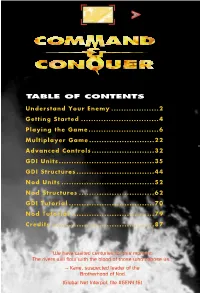

CC-Manual.Pdf

2 C&C OEM v.1 10/23/98 1:35 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Understand Your Enemy ...................2 Getting Started ...............................4 Playing the Game............................6 Multiplayer Game..........................22 Advanced Controls.........................32 GDI Units......................................35 GDI Structures...............................44 Nod Units .....................................52 Nod Structures ..............................62 GDI Tutorial ..................................70 Nod Tutorial .................................79 Credits .........................................87 "We have waited centuries for this moment. The rivers will flow with the blood of those who oppose us." -- Kane, suspected leader of the Brotherhood of Nod (Global Net Interpol, file #GEN4:16) 2 C&C OEM v.1 10/20/98 3:19 PM Page 2 THE BROTHERHOOD OF NOD Commonly, The Brotherhood, The Ways of Nod, ShaÆSeer among the tribes of Godan; HISTORY see INTERPOL File ARK936, Aliases of the Brotherhood, for more. FOUNDED: Date unknown: exaggerated reports place the Brotherhood’s founding before 1,800 BC IDEOLOGY: To unite third-world nations under a pseudo-religious political platform with imperialist tendencies. In actuality it is an aggressive and popular neo-fascist, anti- West movement vying for total domination of the world’s peoples and resources. Operates under the popular mantra, “Brotherhood, unity, peace”. CURRENT HEAD OF STATE: Kane; also known as Caine, Jacob (INTERPOL, File TRX11-12Q); al-Quayym, Amir (MI6 DR-416.52) BASE OF OPERATIONS: Global. Command posts previously identified at Kuantan, Malaysia; somewhere in Ar-Rub’ al-Khali, Saudi Arabia; Tokyo; Caen, France. MILITARY STRENGTH: Previously believed only to be a smaller terrorist operations, a recent scandal involving United States defense contractors confirms that the Brotherhood is well-equipped and supports significant land, sea, and air military operations. -

Disparo En Red 05 Disparo En Red

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 1-9-2005 Disparo en Red 05 Disparo En Red Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Disparo En Red, "Disparo en Red 05 " (2005). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 179. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/179 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOY: 9 de ENERO del 2005 DISPARO EN RED: Boletín electrónico de ciencia-ficción y fantasía. De frecuencia quincenal y totalmente gratis. Editores: darthmota Jartower Colaboradores: Taller de Creación ESPIRAL de ciencia ficción y fantasía. Anabel Enriquez Piñeiro Juan Pablo Noroña. Jorge Enrique Lage. 0. CONTENIDOS: 1.La frase de hoy: J.R.R. Tolkien. 2.Artículo: Anteproyecto para un canon de la CF, César Mallorquí. 3.Cuento clásico: La Puerta del Laberinto, Michael Ende. 4.Cuento made in Cuba: Los que van a morir, Erick Mota. 5.Curiosidades. Consejos de Bruce Sterling. 6.Reseñas. Dune, observaciones sobre la obra de Frank Herbert, por Yeray Rodríguez Domínguez. 7.¿Cómo contactarnos? 1. LA FRASE DE HOY: Supongo que soy un reaccionario. El mainstream de la literatura contemporánea es muy aburrido, ¿no es verdad? Yo estoy ofreciendo un saludable cambio de dieta. J.R.R. -

Terror Ecology: Secrets from the Arrakeen Underground

Terra‐&‐Terror Ecology: Secrets from the Arrakeen Underground Nandita Biswas Mellamphy Western University, Canada It is […] vital to an understanding of Muad'Dib’s religious impact that you never lose sight of one fact: the Fremen were a desert people whose entire ancestry was accustomed to hostile landscapes. Mysticism isn’t difficult when you survive each second by surmounting open hostility […]. With such a tradition, suffering is accepted […]. And it is well to note that Fremen ritual gives almost complete freedom from guilt‐feelings. This isn’t necessarily because their law and religion were identical, making disobedience a sin. It is likely closer to the mark to say they cleansed themselves of guilt easily because their everyday existence required brutal (often deadly) judgments which in a softer land would burden men with unbearable guilt. Dune I (576‐77) This world, which is the same for all, no one of gods or men has made. But it always is, was, and will be an ever‐living Fire, igniting and extinguishing in equal measure. Heraclitus Fragments (DK B30) [F]orm is nothing but holes and cracks […] with a nature that has no hardness or solidity. Ancient Buddhist saying. Frank Herbert’s science‐fiction classic Dune1 is a literary work about political, religious, military and ecological design: a design in which Dune’s desert‐planet is, like fire, a perpetually self‐consuming political, religious, military and ecological topos and in which human beings— among other things like water, sand‐worms and religious doctrines—are the fodder that fuels what could be called the ‘Great Ecology’ of planetary regeneration and desertification. -

Political and Social Issues in French Digital Games, 1982–1993

TRANSMISSIONS: THE JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES 2017, VOL.2, NO. 2, PP. 162-176. Filip Jankowski Jagiellonian University Political and Social Issues in French Digital Games, 1982–1993 Abstract Despite numerous publications about the history of digital games in the United States and Japan, there are few studies which aim to explore the past European trends in game design. For example, the French gaming industry remains unknown to the vast majority of game researchers. However, from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s a certain tendency emerged in this industry: political and social issues became overtly discussed within digital games. To examine such a tendency, the author follows the ‘emancipatory’ paradigm in digital game research (to cite Jaakko Suominen), instead of the ‘enthusiast’ Trans-Pacific-oriented ones. The objects of the analysis are several adventure games developed in France between 1982 and 1993 whose popularity during this period made them influential for the development of the French gaming industry. The author indicates three factors that contributed to the rapid growth of adventure games. These are the advancement of the personal computer market, the modest but existing support from French national institutions, and the article published by Guy Delcourt in the August 1984 issue of Tilt gaming magazine, which gave critical insight into previous development practices and suggested drawing inspiration from current events. The author distinguishes five thematic genres: Froggy Software’s avant-garde digital games, postcolonial and feminist games, investigative games, science fiction, and horror. Each of these provided numerous references to political affairs, economic stagnation and postcolonial critique of the past, which were severe issues in France during the 1980s and 1990s. -

NOX UK Manual 2

NOX™ PCCD MANUAL Warning: To Owners Of Projection Televisions Still pictures or images may cause permanent picture-tube damage or mark the phosphor of the CRT. Avoid repeated or extended use of video games on large-screen projection televisions. Epilepsy Warning Please Read Before Using This Game Or Allowing Your Children To Use It. Some people are susceptible to epileptic seizures or loss of consciousness when exposed to certain flashing lights or light patterns in everyday life. Such people may have a seizure while watching television images or playing certain video games. This may happen even if the person has no medical history of epilepsy or has never had any epileptic seizures. If you or anyone in your family has ever had symptoms related to epilepsy (seizures or loss of consciousness) when exposed to flashing lights, consult your doctor prior to playing. We advise that parents should monitor the use of video games by their children. If you or your child experience any of the following symptoms: dizziness, blurred vision, eye or muscle twitches, loss of consciousness, disorientation, any involuntary movement or convulsion, while playing a video game, IMMEDIATELY discontinue use and consult your doctor. Precautions To Take During Use • Do not stand too close to the screen. Sit a good distance away from the screen, as far away as the length of the cable allows. • Preferably play the game on a small screen. • Avoid playing if you are tired or have not had much sleep. • Make sure that the room in which you are playing is well lit. • Rest for at least 10 to 15 minutes per hour while playing a video game.