Guerrilla Interview with Lorenzo Cornista

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines November 2005 Republika ng Pilipinas PAMBANSANG LUPON SA UGNAYANG PANG-ESTADISTIKA (NATIONAL STATISTICAL COORDINATION BOARD) http://www.nscb.gov.ph in cooperation with The WORLD BANK Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines FOREWORD This report is part of the output of the Poverty Mapping Project implemented by the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) with funding assistance from the World Bank ASEM Trust Fund. The methodology employed in the project combined the 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES), 2000 Labor Force Survey (LFS) and 2000 Census of Population and Housing (CPH) to estimate poverty incidence, poverty gap, and poverty severity for the provincial and municipal levels. We acknowledge with thanks the valuable assistance provided by the Project Consultants, Dr. Stephen Haslett and Dr. Geoffrey Jones of the Statistics Research and Consulting Centre, Massey University, New Zealand. Ms. Caridad Araujo, for the assistance in the preliminary preparations for the project; and Dr. Peter Lanjouw of the World Bank for the continued support. The Project Consultants prepared Chapters 1 to 8 of the report with Mr. Joseph M. Addawe, Rey Angelo Millendez, and Amando Patio, Jr. of the NSCB Poverty Team, assisting in the data preparation and modeling. Chapters 9 to 11 were prepared mainly by the NSCB Project Staff after conducting validation workshops in selected provinces of the country and the project’s national dissemination forum. It is hoped that the results of this project will help local communities and policy makers in the formulation of appropriate programs and improvements in the targeting schemes aimed at reducing poverty. -

Laguna Lake Development and Management

LAGUNA LAKE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Presentation for The Bi-Lateral Meeting with the Ministry of Environment Japan On LAGUNA DE BAY Laguna Lake Development Authority Programs, Projects and Initiatives Presented By: CESAR R. QUINTOS Division Chief III, Planning and Project Development Division October 23, 2007 LLDA Conference Room Basic Fac ts o n Lagu na de Bay “The Lake of Bay” Laguna de Bay . The largest and most vital inland water body in t he Philipp ines. 18th Member of the World’s Living Lakes Network. QUICK FACTS Surface Area: * 900 km2 Average Depth: ~ 2.5 m Maximum Depth: ~ 20m (Diablo Pass) AerageVolmeAverage Volume: 2,250,000,000 m3 Watershed Area: * 2,920 km2 Shoreline: * 285 km Biological Resources: fish, mollusks, plankton macrophytes (* At 10.5m Lake Elevation) The lake is life support system Lakeshore cities/municipalities = 29 to about 13 million people Non-lakeshore cities/municipalities= 32 Total no. of barangays = 2,656 3.5 million of whom live in 29 lakeshore municipalities and cities NAPINDAN CHANNEL Only Outlet Pasig River connects the lake to Manila Bay Sources of surface recharge 21 Major Tributaries 14% Pagsanjan-Lumban River 7% Sta. Cruz River 79% 19 remaining tributary rivers The Pasig River is an important component of the lake ecosystem. It is the only outlet of the lake but serves also as an inlet whenever the lake level is lower than Manila Bay. Salinity Intrusion Multiple Use Resource Fishing Transport Flood Water Route Industrial Reservoir Cooling Irrigation Hydro power generation Recreation Economic Benefits -

Active, Clean, and Bountiful Rivers: the Wetlands Bioblitz Program

Active, clean, and bountiful rivers: The Wetlands BioBlitz Program Ivy Amor Lambio1, Amy Lecciones2, Aaron Julius Lecciones2, Zenaida Ugat2, Jose Carlo Quintos2, Darry Shel Estorba2 1 Assistant Professor, University of the Philippines Los Baños 2Society for the Conservation of Philippine Wetlands Presentation Outline I. What is Bioblitz? II. What is Wetland Bioblitz? III. Who are involved in Wetlands Bioblitz? IV. What are the parameters involved in Wetlands Bioblitz? V. Launching Event - Active, Bountiful, and Clean Rivers: Wetlands Bioblitz VI. A Project: Wetlands BioBlitz at the Laguna de Bay Region Wetlands BioBlitz What is BioBlitz? • ‘Bio’ means ‘life’ and ‘Blitz’ means ‘to do something quickly and intensively’. • a collaborative race against the clock to document as many species of plants, animals and fungi as possible, within a set location, over a defined time period (usually 24 hours) • a biological inventory A bioblitz differs from a scientific inventory - • Scientific inventories are usually limited to biologists, geographers, and other scientists. • A bioblitz brings together volunteer scientists, as well as families, students, teachers, and other members of the community. Wetlands BioBlitz What is Wetlands BioBlitz? • An adoptation by the SCPW designed for wetlands • Added dimensions including geographical, climate-related and ecosystem services as indicated in the Ramsar Information Sheet or the locally adopted Wetland Information Sheet • It also uses the Ramsar Assessment of Wetland Ecosystem Services or RAWES. Wetlands BioBlitz What is Wetlands BioBlitz? General objective: To characterize and assess priority rivers employing citizen-science and increase the awareness and capacity of local communities to take action for their wise use. Specific objectives: • To identify the flora, fauna and fungi found in selected rivers • To learn about river ecosystems, the benefits derived from them, and initiatives to manage and conserve them. -

An Integrated Development Analysis on the Province of Laguna in the Philippines a Case Study

Overseas Fieldwork Report 1995 : An Integrated Development Analysis on the Province of Laguna in the Philippines A Case Study March 1996 Graduate School of International Development Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan Contents page Introduction Working Group 1 Economic Development in Laguna 7 Working Group 2 Human Development: Education & Health 33 Working Group 3 Environment and Infrastructure 53 Working Group 4 Institutional Development 73 Integration and Policy Direction: Synthesis 93 Integration of Group Reports OFW 95-PHl:Part 2 103 Introduction Introduction This is our fourth report on the result of the Overseas Fieldwork which was conducted in Laguna Province in the Philippines (see Map 1) from September 20-0ctober 19, 1995 (hereafter "OFW '95-PHI"). OFW '95-PHI was conducted under the academic exchange program between the Graduate School of International Development (GSID) of Nagoya University and the University of the Philippines at Los Banos (UPLB) following OFW '94-PHI which took place in Cavite Province. This time, 25 graduate students (14 female and 11 male) participated in OFW '95-PHI which was designed as an integral part of our formal curricular activities (participants' names and itinerary are listed on page 3-4). The students were divided into the following four working groups (WG) based on their initial interests of field research: WG-1: Economic development (agriculture and non-agriculture) WG-2: Human resource development (education and health) WG-3: Physical development (infrastructure and environmental protection) WG-4: Institutional development (public administration and NGOs, POs). In conducting actual fieldwork, the above four groups were subdivided into eight groups as indicated in parentheses. -

Shaping Lumban Women Hand Embroiderers' Identity

SELF-REPRESENTATION: Shaping Lumban Women Hand Embroiderers’ Identity Kristine K. Adalla* ABSTRACT Embroidery is an insightful source for studying the articulation and expression of identity. Meaningful discoveries can surface through examining the interaction and relations that are connected in the production of hand embroidered products. Embroidery, as a female craft, symbolizes and reflects the women’s lived experiences. As a center of missionary activities during the Spanish regime in the Philippines, Lumban women hand embroiderers shaped their identity through being exposed to the craft at an early age. Through a creative workshop, it revealed that gender and ethnicity are the two essential factors in shaping their identity. Their perception of their individual identities constitutes the socially constructed roles and behaviors or traits that a woman must possess. Moreover, familial tradition and skills in embroidery helped shape their individual identity as women hand embroiderers, while their collective identity resulted from their strong affinity with their locality, as well as the relationships and friendships that they built as a community of embroiderers. Keywords: embroidery, identity, lived experiences, gender, self- representation 29 Adalla / SELF-REPRESENTATION: Shaping Lumban Women Hand Embroiderers’ Identity “Lumban is the only town in Laguna where embroidery has flourished as a major industry, probably because it was the center of missionary activities in the province and therefore, the first students of the art came from here.”1 Lumban is known as the Embroidery Capital of the Philippines. Hand embroidery on fine jusi and piña cloth produces the barong tagalog worn by men and the saya (Filipiñana) worn by women, which are also exported abroad. -

The Land of Heroes and Festivities Calabarzon

Calabarzon The land of heroes and festivities is an acronym for the provinces comprising Getting There the region – CAvite, LAguna, BAtangas, Rizal Travelers can take air-conditioned buses going to southern and QueZON. It is situated immediately Luzon from among the multitudes of bus terminals within Calabarzon Metro Manila. Travel time to Cavite and Rizal usually takes south and east of Metro Manila, and is the an hour while Batangas, Laguna and Quezon may be complementary hideaway for anyone reached within two to four hours. looking to escape the hustle and bustle of Hotels and Resorts the capital. The region has a good collection of accommodation facilities that offer rest and recreation at stunningly-low Calabarzon is rich with stories relating to prices. From classy deluxe resort hotels to rental apartment options, one will find rooms, apartments and evens the country’s colonial past, of heroes and mansions that are suitable for every group of any size. revolutionaries standing up for the ideals of Spa resorts in Laguna and elsewhere are particularly popular, as individual homes with private springs are freedom and self-rule. Many monuments offered for day use, or longer. still stand as powerful reminders of days Sports Activities and Exploration gone by, but the region hurtles on as one of The region is blessed with an extensive selection the most economically-progressive areas of sport-related activities, such as golf in world-class for tourism, investments and trade. championship courses in Cavite, or volcano-trekking around Taal Lake, or diving off the magnificent coasts and Its future is bright and the way clear, thanks islands of Batangas, among others. -

Pasig-Marikina-Laguna De Bay Basins

Philippines ―4 Pasig-Marikina-Laguna de Bay Basins Map of Rivers and Sub-basins 178 Philippines ―4 Table of Basic Data Name: Pasig-Marikina-Laguna de Bay Basins Serial No. : Philippines-4 Total drainage area: 4,522.7 km2 Location: Luzon Island, Philippines Lake area: 871.2 km2 E 120° 50' - 121° 45' N 13° 55' - 14° 50' Length of the longest main stream: 66.8 km @ Marikina River Highest point: Mt. Banahao @ Laguna (2,188 m) Lowest point: River mouth @ Laguna lake & Manila bay (0 m) Main geological features: Laguna Formation (Pliocene to Pleistocene) (1,439.1 km2), Alluvium (Halocene) (776.0 km2), Guadalupe Formation (Pleistocene) (455.4 km2), and Taal Tuff (Pleistocene) (445.1 km2) Main land-use features: Arable land mainly sugar and cereals (22.15%), Lakes & reservoirs (19.70%), Cultivated area mixed with grassland (17.04%), Coconut plantations (13.03%), and Built-up area (11.60%) Main tributaries/sub-basins: Marikina river (534.8 km2), and Pagsanjan river (311.8 km2) Mean annual precipitation of major sub-basins: Marikina river (2,486.2 mm), and Pagsanjan river (2,170 mm) Mean annual runoff of major sub-basins: Marikina river (106.4 m3/s), Pagsanjan river (53.1 m3/s) Main reservoirs: Caliraya Reservoir (11.5 km2), La Mesa reservoir (3.6 km2) Main lakes: Laguna Lake (871.2 km2) No. of sub-basins: 29 Population: 14,342,000 (Year 2000) Main Cities: Manila, Quezon City 1. General Description Pasig-Marikina-Laguna de Bay Basin, which is composed of 3651.5 km2 watershed and 871.2 km2 lake, covers the Metropolitan Manila area (National Capital Region) in the west, portions of the Region III province of Bulacan in the northwest, and the Region IV provinces of Rizal in the northeast, Laguna and portions of Cavite and Batangas in the south. -

Chapter 4 Safety in the Philippines

Table of Contents Chapter 1 Philippine Regions ...................................................................................................................................... Chapter 2 Philippine Visa............................................................................................................................................. Chapter 3 Philippine Culture........................................................................................................................................ Chapter 4 Safety in the Philippines.............................................................................................................................. Chapter 5 Health & Wellness in the Philippines........................................................................................................... Chapter 6 Philippines Transportation........................................................................................................................... Chapter 7 Philippines Dating – Marriage..................................................................................................................... Chapter 8 Making a Living (Working & Investing) .................................................................................................... Chapter 9 Philippine Real Estate.................................................................................................................................. Chapter 10 Retiring in the Philippines........................................................................................................................... -

Local Franchise

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR AUTHORITY TO INCLUDE IN CUSTOMER'S BILL A TAX RECOVERY ADJUSTMENT CLAUSE (TRAC) FOR FRANCHISE TAXES PAID IN THE PROVINCE OF LAGUNA AND BUSINESS TAX PAID IN THE MUNICIPALITIES OF PANGIL, LUMBAN,PAGSANJAN AND PAKIL ALL IN THE PROVINCE OF LAGUNA ERC CASE NO. 2013-002 CF FIRST ,LAGUNA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (FLECO), Applicant. x- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x DECISION Before this Commission for resolution is the application filed on January 8, 2013 by the First Laguna Electric Cooperative, Inc, (FLECO) for authority to include in its customer's bill a Tax Recovery Adjustment Clause (TRAC) for franchise taxes paid to the Province of Laguna and business taxes paid to the Municipalities of Pangil, Lumban, Pagsanjan and Pakil, all in the Province of Laguna. In the said application, FLECO alleged, among others, that: 1. It is a non-stock non-profit electric cooperative (EC) duly organized and existing under and by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines. It is represented by its Board President, Mr. Gabriel C. Adefuin, It has its principal office at Barangay Lewin, Lumban, Laguna; " ERC CASE NO. 2013-002 CF DECISION/April 28, 2014 Page 2 of 18 2. It is the exclusive holder of a franchise issued by the National Electrification Administration (NEA) to operate an electric light and power services in the Municipalities of Cavinti, Pagsanjan, Lumban, Kalayaan, Paete, Pakil, Pangil, Siniloan, Famy, Mabitac, and Sta. Maria, all in the Province of Laguna; 3. -

Coverpage RPFP Vol 2 Updated

REGION IV-A (CALABARZON) REGIONAL PHYSICAL FRAMEWORK PLAN 2004-2030 (Volume 2 - Physical and Socio-Economic Profile and Situational Analysis) Philippine Copyright @ 2008 National Economic and Development Authority Regional Office IV-A (CALABARZON) Printed in Quezon City, Philippines Table of Contents List of Tables List of Figures List of Acronyms Acknowledgement Other Sources of Data/Information A. PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT 1 PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS 1.1 Location and Political Subdivision 2 1.2 Land Area and Land Classification 3 1.3 Topography 4 1.4 Slope 5 1.5 Soil physiology and suitability 6 1.6 Rock type and their distribution 9 1.7 Climate 9 1.8 Water Resources 10 1.9 Mineral Resources 10 1.10 Volcanoes 13 2 LAND USE 2.1 Production Land Use 14 2.1.1 Agricultural Land 14 a. Existing Agricultural Land Use in the NPAAAD b. Existing Land Use of the SAFDZ iii Table of Contents 2.1.2 Livestock and Poultry Production Areas 18 2.1.3 Fishery Resources 20 a. Major Fishing Grounds b. Municipal Fishing c. Municipal Fisherfolks 2.1.4 Highlight of Agricultural Performance and 21 Food Sufficiency a. Crops, Livestock and Poultry b. Fishing Production Performance c. Food Sufficiency Level\Feed Sufficiency 2.1.5 Agrarian Reform Areas 23 a. Land Acquisition and Distribution b. Agrarian Reform Communities (ARCs) 2.1.6 Mineral Resources 25 a. Metallic Minerals b. Non-Metallic Minerals c. Mining Permits Issues 2.1.7 Industrial Development Areas 28 a. Industrial Center b. Ecozones 2.1.8 Tourism 34 a. Tourism Areas b. Foreign and Domestic Tourist Travel Movements 2.2 Protection Land Use 40 2.2.1 National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS) 40 a. -

AWARDED SOLAR PROJECTS As of 30 JUNE 2020

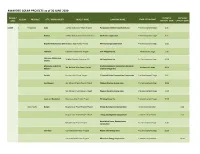

AWARDED SOLAR PROJECTS as of 30 JUNE 2020 . ISLAND / POTENTIAL INSTALLED REGION PROVINCE CITY / MUNICIPALITY PROJECT NAME COMPANY NAME STAGE OF CONTRACT GRID CAPACITY (MW) CAPACITY (MW) LUZON I Pangasinan Anda 1 MWp Anda Solar Power Project Pangasinan I Electric Cooperative, Inc. Pre-Development Stage 0.00 Bolinao 5 MWp Bolinao Solar PV Power Plant EEI Power Corporation Pre-Development Stage 5.00 Bugallon & San Carlos City Bugallon Solar Power Project Phinma Energy Corporation Pre-Development Stage 1.03 Labrador Labrador Solar Power Project IJG1 Philippines Inc. Development Stage 5.00 Labrador, Mabini and 90 MW Cayanga- Bugallon SPP PV Sinag Power Inc. Pre-Development Stage 90.00 Infanta Mapandan and Santa OneManaoag Solar Corporation (Formerly Sta. Barbara Solar Power Project Development Stage 10.14 Barbara SunAsia Energy Inc.) Rosales Rosales Solar Power Project C Squared Prime Commodities Corporation Pre-Development Stage 0.00 San Manuel San Manuel 2 Solar Power Project Pilipinas Einstein Energy Corp. Pre-Development Stage 70.00 San Manuel 1 Solar Power Project Pilipinas Newton Energy Corp. Pre-Development Stage 70.00 Sison and Binalonan Binalonan Solar Power Project PV Sinag Power Inc. Pre-Development Stage 50.00 Ilocos Norte Burgos Burgos Solar Power Project Phase I Energy Development Corporation Commercial Operation 4.10 Burgos Solar Power Project Phase 2 Energy Development Corporation Commercial Operation 2.66 NorthWind Power Development Bangui Solar Power Project Pre-Development Stage 2.50 Corporation Currimao Currimao Solar Power Project. Nuevo Solar Energy Corp. Pre-Development Stage 50.00 Currimao Solar Power Project.. Mirae Asia Energy Corporation Commercial Operation 20.00 . -

2020 Sustainability Report Contents About the Report

Enabling Infrastructure Development for National Progress 2020 Sustainability Report Contents About the Report This is the fifth sustainability report of Metro Pacific Investments Corporation (MPIC, the Company or the Parent Company) containing information about our economic, environmental, social, and governance (ESG or Sustainability) impacts for the year ending December 2020. This report should be read in conjunction with our SEC Part 1: Form 17A and our 2020 Information Statement. In line with our commitment to transparency and accountability, we have prepared this report in accordance with the Contributing to National Progress and 1 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Industry Standards, United Nations Improving the Quality of Life of Filipinos Global Compact Index (UNGC), and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards: Core Option. DNV has provided an independent assurance statement for our sustainability or non-financial disclosures. We welcome feedback on this report and any matter concerning the sustainability performance of our business. Part 2: Please contact us at: Our Sustainability Pillars 25 Metro Pacific Investments Corporation Investor Relations 10/F MGO Building, Legaspi corner Dela Rosa Streets, Makati City, 0721, Philippines +63 2 8888 0888 [email protected] Annex The 2020 Sustainability Report was published on 80 April 5, 2021 and is also available for download from the corporate website. Part 1: Contributing to National Progress and Improving the Quality of Life of Filipinos Part 2: Our Sustainability