Sid Meier: More Than Just a Brand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategiset Suunnittelupelit: Simcity Ja Civilization

Strategiset suunnittelupelit: SimCity ja Civilization Pekka Hytinkoski HY, Ruralia-instituutti [email protected] Kaupunginrakennus- ja sivilisaatiosimulaatio (managerointipelit) Will Wright julkaisi vuonna 1989 SimCity-pelin, joka sekä aloitti menestyksekkään SimCity-pelisarjan (yli 18 miljoonaa myytyä peliä), loi käsitteen Sim-pelit (Sims, SimEarth, SimGolf, SimFarm, Spore jne.) että rohkaisi muita tulevia strategiapelien suunnittelijoita (Sid Meier: Civilization-pelisarjat; Peter Molyneux: Populous-, Black and White-, Dungeon Keeper -pelisarjat; Settlers- pelisarja, Age of Empires –pelisarja, ”Tycoon-pelit” – esim. Railroad Tycoon yms.) Sid Meierin Civilization –pelisarjan (yli 8 miljoonaa myytyä peliä) ensimmäinen osa julkaistiin 1991 ja ne ovat olleet alusta lähtien suosittuja strategiapelaajien ja peliarvostelijoiden keskuudessa. Sarjan kehuttu neljäs osa ilmestyi 2005, seuraavan viidennen osan odotetaan ilmestyvän loppuvuonna 2010. SimCity On open-ended –tyylinen strategia/managerointi-peli, jossa pelaajan tehtävä on rakentaa alusta lähtien toimiva ja taloudellisesti, ekologisesti ja sosiaalisesti kestävä kaupunki. Peli perustuu MIT:n professori Jay Forresterin Urban dynamics (1969) teokseen ja tietokonesimulaatioihin. Jos tämä onnistuu, niin peli ei pääty periaatteessa koskaan, vaan pelaaja pystyy koko ajan sekä laajentamaan, uudelleen rakentamaan että hienosäätämään kaupunkiaan. Peli alkaa satunnaisgeneraattorin luomasta ympäristöstä, jossa pelaajan tulee ”pormestarina” tehdä alusta lähtien oikeita ratkaisuja asuinalueiden, -

Cultural Imaginations of Piracy in Video Games

FORUM FOR INTER-AMERICAN RESEARCH (FIAR) VOL. 11.2 (SEP. 2018) 30-43 ISSN: 1867-1519 © forum for inter-american research “In a world without gold, we might have been heroes!” Cultural Imaginations of Piracy in Video Games EUGEN PFISTER (HOCHSCHULE DER KÜNSTE BERN) Abstract From its beginning, colonialism had to be legitimized in Western Europe through cultural and political narratives and imagery, for example in early modern travel reports and engravings. Images and tales of the exotic Caribbean, of beautiful but dangerous „natives“, of unbelievable fortunes and adventures inspired numerous generations of young men to leave for the „new worlds“ and those left behind to support the project. An interesting figure in this set of imaginations in North- Western Europe was the “pirate”: poems, plays, novels and illustrations of dashing young rogues, helping their nation to claim their rightful share of the „Seven Seas“ achieved major successes in France, Britain the Netherlands and beyond. These images – regardless of how far they might have been from their historical inspiration – were immensely successful and are still an integral and popular part of our narrative repertoire: from novels to movies to video games. It is important to note that the “story” was – from the 18th century onwards –almost always the same: a young (often aristocratic) man, unfairly convicted for a crime he didn’t commit became an hors-la-loi against his will but still adhered to his own strict code of conduct and honour. By rescuing a city/ colony/princess he redeemed himself and could be reintegrated into society. Here lies the morale of the story: these imaginations functioned also as acts of political communication, teaching “social discipline”. -

2K Unveils Stellar Video Game Line

2K Unveils Stellar Video Game Line-up for 2006 Electronic Entertainment Expo; Line-up Includes Highly- Anticipated Titles such as The Da Vinci Code(TM), Prey, Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Warlords and NBA 2K7 May 10, 2006 8:31 AM ET NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--May 10, 2006--2K and 2K Sports, publishing labels of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (NASDAQ: TTWO), today announced a strong line-up for Electronic Entertainment Expo 2006 (E3) taking place at the Los Angeles Convention Center from May 10-12, 2006. From 2K, the line-up includes titles based on blockbuster entertainment brands such as The Da Vinci Code(TM) and Family Guy and popular comic book franchises The Darkness and Ghost Rider, as well as original next generation games such as Prey and BioShock. 2K is also featuring highly-anticipated titles from Firaxis Games, including Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Warlords and Sid Meier's Railroads! as well as the Firaxis and Firefly Studios collaboration title CivCity: Rome. Other eagerly awaited titles include Stronghold Legends(TM) along with Dungeon Siege II(R): Broken World(TM) and Dungeon Siege: Throne of Agony(TM), based on the acclaimed Dungeon Siege(R) franchise. In addition, the 2K Sports line-up features the next installments from top-rated franchises such as NHL 2K7, NBA 2K7 and College Hoops 2K7. 2K Line-up Includes: BioShock BioShock is an innovative role-playing shooter from Irrational Games who was named IGN's 2005 Developer of the Year. BioShock immerses players into a war-torn underwater utopia, where mankind has abandoned their humanity in their quest for perfection. -

Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C

04 3677_CH03 6/3/03 12:30 PM Page 67 Chapter 3 THE EXPERTS • Sid Meier, Firaxis General Game Design: • Bill Roper, Blizzard North • Brian Reynolds, Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C. Shelley, Ensemble Studios • Peter Molyneux, Do you like to use some brains along with (or instead of) brawn Lionhead Studios when gaming? This chapter is for you—how to create breathtaking • Alex Garden, strategy games. And do we have a roundtable of celebrities for you! Relic Entertainment Sid Meier, Firaxis • Louis Castle, There’s a very good reason why Sid Meier is one of the most Electronic Arts/ accomplished and respected game designers in the business. He Westwood Studios pioneered the industry with a number of unprecedented instant • Chris Sawyer, Freelance classics, such as the very first combat flight simulator, F-15 Strike Eagle; then Pirates, Railroad Tycoon, and of course, a game often • Rick Goodman, voted the number one game of all time, Civilization. Meier has con- Stainless Steel Studios tributed to a number of chapters in this book, but here he offers a • Phil Steinmeyer, few words on game inspiration. PopTop Software “Find something you as a designer are excited about,” begins • Ed Del Castillo, Meier. “If not, it will likely show through your work.” Meier also Liquid Entertainment reminds designers that this is a project that they’ll be working on for about two years, and designers have to ask themselves whether this is something they want to work on every day for that length of time. From a practical point of view, Meier says, “You probably don’t want to get into a genre that’s overly exhausted.” For me, working on SimGolf is a fine example, and Gettysburg is another—something I’ve been fascinated with all my life, and it wasn’t mainstream, but was a lot of fun to write—a fun game to put together. -

2K Announces Sid Meier's Civilization® VI for Nintendo Switch September

2K Announces Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI for Nintendo Switch September 13, 2018 6:46 PM ET The full Civilization VI experience comes to a home console for the first time Join the conversation on Twitter using the hashtag #OneMoreTurn NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Sep. 13, 2018-- 2K and Firaxis Games today announced that Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI, winner of The Game Awards’ Best Strategy Game, DICE Awards’ Best Strategy Game and latest entry in the prestigious Civilization franchise, is coming to Nintendo Switch™ on November 16, 2018. Additionally, 2K and Firaxis Games have partnered with Aspyr Media to bring Civilization VI to Nintendo Switch and ensure the experience meets the same high standards of the beloved series. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home /20180913005109/en/ Originally created by legendary game designer, Sid Meier, Civilization is a turn-based strategy game in which you build an empire to stand the 2K and Firaxis Games today announced that Sid test of time. Explore a new land, research technology, conquer your Meier's Civilization® VI, winner of The Game Awards' Best Strategy Game, DICE Awards' Best enemies, and go head-to-head with history’s most renowned leaders as Strategy Game and latest entry in the prestigious you attempt to build the greatest civilization the world has ever known. Civilization franchise, is coming to Nintendo Switch™ on November 16, 2018. (Graphic: Business Now on Nintendo Switch, the quest to victory in Civilization VI can Wire) take place wherever and whenever players want. -

John Carmack Archive - .Plan (1998)

John Carmack Archive - .plan (1998) http://www.team5150.com/~andrew/carmack March 18, 2007 Contents 1 January 5 1.1 Some of the things I have changed recently (Jan 01, 1998) . 5 1.2 Jan 02, 1998 ............................ 6 1.3 New stuff fixed (Jan 03, 1998) ................. 7 1.4 Version 3.10 patch is now out. (Jan 04, 1998) ......... 8 1.5 Jan 09, 1998 ............................ 9 1.6 I AM GOING OUT OF TOWN NEXT WEEK, DON’T SEND ME ANY MAIL! (Jan 11, 1998) ................. 10 2 February 12 2.1 Ok, I’m overdue for an update. (Feb 04, 1998) ........ 12 2.2 Just got back from the Q2 wrap party in vegas that Activi- sion threw for us. (Feb 09, 1998) ................ 14 2.3 Feb 12, 1998 ........................... 15 2.4 8 mb or 12 mb voodoo 2? (Feb 16, 1998) ........... 19 2.5 I just read the Wired article about all the Doom spawn. (Feb 17, 1998) .......................... 20 2.6 Feb 22, 1998 ........................... 21 1 John Carmack Archive 2 .plan 1998 3 March 22 3.1 American McGee has been let go from Id. (Mar 12, 1998) . 22 3.2 The Old Plan (Mar 13, 1998) .................. 22 3.3 Mar 20, 1998 ........................... 25 3.4 I just shut down the last of the NEXTSTEP systems running at id. (Mar 21, 1998) ....................... 26 3.5 Mar 26, 1998 ........................... 28 4 April 30 4.1 Drag strip day! (Apr 02, 1998) ................. 30 4.2 Things are progressing reasonably well on the Quake 3 en- gine. (Apr 08, 1998) ....................... 31 4.3 Apr 16, 1998 .......................... -

Quake Manual

The Story QUAKE Background: You get the phone call at 4 a.m. By 5:30 you're in the secret installation. The commander explains tersely, "It's about the Slipgate device. Once we perfect these, we'll be able to use them to transport people and cargo from one place to another instantly. "An enemy codenamed Quake, is using his own slipgates to insert death squads inside our bases to kill, steal, and kidnap. "The hell of it is we have no idea where he's from. Our top scientists think Quake's not from Earth, but another dimension. They say Quake's preparing to unleash his real army, whatever that is. "You're our best man. This is Operation Counterstrike and you're in charge. Find Quake, and stop him ... or it ... You have full authority to requisition anything you need. If the eggheads are right, all our lives are expendable." Prelude to Destruction: While scouting the neighborhood, you hear shots back at the base. Damn, that Quake bastard works fast! He heard about Operation Counterstrike, and hit first. Racing back, you see the place is overrun. You are almost certainly the only survivor. Operation Counterstrike is over. Except for you. You know that the heart of the installation holds a slipgate. Since Quake's killers came through, it is still set to his dimension. You can use it to get loose in his hometown. Maybe you can get to the asshole personally. You pump a round into your shotgun, and get moving. System Requirements General Quake System Requirements IBM PC and Compatible Computers Pentium 75 MHz processor or better (absolutely must have a Math Co-Processor!) VGA Compatible Display or better Windows 95 Operation: 16MB RAM minimum, 24MB+ recommended CD-ROM drive required Hard Drive Space Needed: 80 MB Specialized Requirements For WinQuake (WINQUAKE.EXE): Windows 95/98/ME/NT/2000 For GLQuake (GLQUAKE.EXE): Windows 95/98/ME/NT/2000 Open GL Compatible Video Card GLQUAKE supports most 100% fully OpenGL compliant 3D accelerator cards. -

Railroad Tycoon Deluxe Cheats

Railroad tycoon deluxe cheats Railroad Tycoon Deluxe. Cheatbook is the resource for the latest Cheats, tips, cheat codes, unlockables, hints and secrets to get the edge to win. For Sid Meier's Railroad Tycoon on the PC, GameFAQs has 15 cheat codes and secrets. Sid Meier's Railroad Tycoon Deluxe PC Cheats: Go to the Regional Display and press Shift+4. It gives you $, Don't use it after you reach $30,, or. Railroad Tycoon Cheats - PC Cheats: This page contains a list of cheats, codes, Easter eggs, tips, and other secrets for Railroad Tycoon for PC. Railroad Tycoon Deluxe Extra money: ______ Press [Shift] + 4 at the top layer of maps. more money: Hold down Alt Gr an press 4 and you gett , Online Games Source for PC Railroad Tycoon Deluxe Cheat Codes, Cheats, Walkthroughs, Strategy Guides, Hint, Tips, Tricks, Secrets and FAQs. Railroad Tycoon Deluxe for PC cheats - Cheating Dome has all the latest cheat codes, unlocks, hints and game secrets you need. Cheats, hints, tricks, walkthroughs and more for Sid Meier's Railroad Tycoon Deluxe (DOS). Cheats, Tips, Tricks, Video Walkthroughs and Secrets for Railroad Tycoon Deluxe on the PC, with a game help system for those that are stuck. The best place to get cheats, codes, cheat codes, walkthrough, guide, FAQ, unlockables, tricks, and Get exclusive Railroad Tycoon trainers at Cheat Happens. This page contains Railroad Tycoon Deluxe cheats, hints, walkthroughs and more for PC. Railroad Tycoon Deluxe. Right now we have 2 Cheats and etc for this. Sid Meier's Railroad Tycoon Deluxe hints. Hey all, Sharp here well don't let this game's complicated look turn you away from it. -

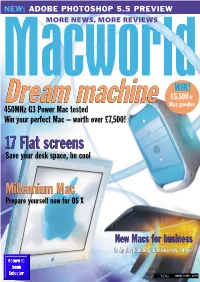

MACWORLD AUGUST 1999 DREAM MACHINE • FLAT-PANEL DISPLAYS • SCSI CARDS • MAC OS X • FINAL CUT PRO • PHOTOSHOP 5.5 Read Me First Simon Jary, Editor-In-Chief

NEW: ADOBE PHOTOSHOP 5.5 PREVIEW MACWORLD MORE NEWS, MORE REVIEWS AUGUST 1999 AUGUST DREAM MACHINE • FLAT-PANEL DISPLAYS • SCSI CARDS • MAC OS X • FINAL CUT PRO • PHOTOSHOP 5.5 OS X • FINAL CUT PRO PHOTOSHOP • SCSI CARDS • MAC DISPLAYS • FLAT-PANEL DREAM MACHINE Macworldwww.macworld.co.uk WIN! £5,500+ Dream machine Mac goodies 450MHz G3 Power Mac tested Win your perfect Mac – worth over £7,500! 17 Flat screens Save your desk space, be cool Millennium Mac Prepare yourself now for OS X New Macs for business Is Apple planning a brand new range? AUGUST 1999 £4.99 read me first Simon Jary, editor-in-chief ast year’s dramatic decision by Apple There was a stand-off. Instead of admitting its previous perilous state and to flounce out of its only UK Mac show getting on with knocking the socks off the beige pretenders, Apple stamped L caused chaos and confusion among its foot until the organizers jumped. And instead of seizing the initiative and exhibitors and visitors alike.Whatever the creating the best Mac show ever, the organizers faffed around with dumb warped reasoning, the swift exit by the principal ideas until they came up with a stupid, Siamese-twin-type show of two halves SHUT YOUR EYES AND IMAGINE YOU’VE attraction devalued Apple Expo to the point of it that suited no one and confused the bejesus out of everyone. becoming more a mini-market for resellers than a grand exhibition of the Apple jumped ship.You could see its point, but nothing could obscure the 61 JUST BEEN GIVEN £7,500 TO BUY YOUR state of the Mac. -

Into the Cosmos: Board Game Project Blending 4X and Eurogame Styles

Salvation: Into the Cosmos: Board Game Project Blending 4X and Eurogame Styles A Senior Project Presented To: the Faculty of the Liberal Arts and Engineering Studies Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Engineering Studies by Zachary Griffith June 2017 © Zachary Griffith 2017 Griffith 1 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 How to Play................................................................................................................................................... 3 Blending Eurogames and 4X ........................................................................................................................ 3 Eurogames ....................................................................................................................................... 3 4X Strategy ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Putting it All Together ...................................................................................................................... 4 Influences ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 The Game Design Process ........................................................................................................................... -

Dokument Informacyjny

CREATIVEFORGE GAMES SPÓŁKA AKCYJNA z siedzibą w Warszawie DOKUMENT INFORMACYJNY sporządzony w związku z ubieganiem się o wprowadzenie do obrotu na rynku NewConnect, prowadzonym jako Alternatywny System Obrotu (ASO) przez Giełdę Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie S.A.: - 450.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii A - 150.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii B - 150.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii C - 150.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii D - 150.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii E - 300.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii F - 150.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii G - 194.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii H - 170.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii I - 136.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii J - 667.000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii K. Niniejszy Dokument Informacyjny został sporządzony w związku z ubieganiem się o wprowadzenie instrumentów finansowych objętych tym dokumentem do obrotu w alternatywnym systemie obrotu prowadzonym przez Giełdę Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie S.A. Wprowadzenie instrumentów finansowych do obrotu w alternatywnym systemie obrotu nie stanowi dopuszczenia ani wprowadzenia tych instrumentów do obrotu na rynku regulowanym prowadzonym przez Giełdę Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie S.A. (rynku podstawowym lub równoległym). Inwestorzy powinni być świadomi ryzyka, jakie niesie za sobą inwestowanie w instrumenty finansowe notowane w alternatywnym systemie obrotu, a ich decyzje inwestycyjne powinny być poprzedzone właściwą analizą, a także, jeżeli wymaga tego sytuacja, konsultacją z doradcą inwestycyjnym. Treść niniejszego Dokumentu Informacyjnego nie była zatwierdzana przez Giełdę Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie S.A. pod względem zgodności informacji w nim zawartych ze stanem faktycznym lub przepisami prawa. Warszawa, dnia 17 maja 2018 roku Autoryzowany Doradca: Trigon Dom Maklerski S.A. -

10Th IAA FINALISTS ANNOUNCED

10th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards Finalists GAME TITLE PUBLISHER DEVELOPER CREDITS Outstanding Achievement in Animation ANIMATION DIRECTOR LEAD ANIMATOR Gears of War Microsoft Game Studios Epic Games Aaron Herzog & Jay Hosfelt Jerry O'Flaherty Daxter Sony Computer Entertainment ReadyatDawn Art Director: Ru Weerasuriya Jerome de Menou Lego Star Wars II: The Original Trilogy LucasArts Traveller's Tales Jeremy Pardon Jeremy Pardon Rayman Raving Rabbids Ubisoft Ubisoft Montpellier Patrick Bodard Patrick Bodard Fight Night Round 3 Electronic Arts EA Sports Alan Cruz Andy Konieczny Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction VISUAL ART DIRECTOR TECHNICAL ART DIRECTOR Gears of War Microsoft Game Studios Epic Games Jerry O'Flaherty Chris Perna Final Fantasy XII Square Enix Square Enix Akihiko Yoshida Hideo Minaba Call of Duty 3 Activison Treyarch Treyarch Treyarch Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six: Vegas Ubisoft Ubisoft Montreal Olivier Leonardi Jeffrey Giles Viva Piñata Microsoft Game Studios Rare Outstanding Achievement in Soundtrack MUSIC SUPERVISOR Guitar Hero 2 Activision/Red Octane Harmonix Eric Brosius SingStar Rocks! Sony Computer Entertainment SCE London Studio Alex Hackford & Sergio Pimentel FIFA 07 Electronic Arts Electronic Arts Canada Joe Nickolls Marc Ecko's Getting Up Atari The Collective Marc Ecko, Sean "Diddy" Combs Scarface Sierra Entertainment Radical Entertainment Sound Director: Rob Bridgett Outstanding Achievement in Original Music Composition COMPOSER Call of Duty 3 Activison Treyarch Joel Goldsmith LocoRoco Sony Computer