A Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variational Text Linguistics: Revisiting Register in English

Christoph Schubert and Christina Sanchez-Stockhammer (Eds.) Variational Text Linguistics Topics in English Linguistics Editors Elizabeth Closs Traugott Bernd Kortmann Volume 90 Variational Text Linguistics Revisiting Register in English Edited by Christoph Schubert Christina Sanchez-Stockhammer ISBN 978-3-11-044310-3 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-044355-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-043533-7 ISSN 1434-3452 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Brian Stablyk/Photographer’s Choice RF/Getty Images Typesetting: fidus Publikations-Service GmbH, Nördlingen Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements The foundations for this edited collection of articles were laid at the interna- tional conference Register revisited: New perspectives on functional text variety in English, which took place at the University of Vechta, Germany, from June 27 to 29, 2013. The aim of the present volume is to conserve the research papers and many inspiring discussions which were stimulated then and to make them available to a larger audience. It was only possible to achieve this aim thanks to the help of many people joining us in the effort. First and foremost, we would like to thank all contributors for their continued cooperation in this project. -

Biology 3596B – Genomics and Beyond – Winter 2021

Department of Biology BIOLOGY 3596B – GENOMICS AND BEYOND – WINTER 2021 Welcome to Bio 3596! My goal is to help you learn and be successful! Please, read and keep this course outline handy, because it is an official document that contains important course information. 1. General Course Information ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Course Information ............................................................................................................................ 2 Course description .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 List of Prerequisites ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 Mode of delivery ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Technical requirements: ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2. Online Participation and Engagement: contribution to community learning ....................................... 3 1.3. Key Sessional Dates ........................................................................................................................... -

CHARON-AXP V4.9 for Linux Users Guide

Document number: 60-16-034-001 CHARON-AXP V4.9 for Linux Users Guide September, 2018 1 / 255 Contents Introduction . 3 Conventions . 6 CHARON-AXP for Linux installation . 7 Running CHARON-AXP for Linux . 22 CHARON-AXP for Linux configuration . 27 Migration to CHARON-AXP for Linux . 43 CHARON-AXP for Linux virtual network . 51 CHARON-AXP for Linux licensing . 55 CHARON-AXP for Linux utilities . 65 mkdskcmd . 66 mtd . 69 hasp_srm_view . 71 hasp_update . 73 ncu . 74 CHARON Guest Utilities for OpenVMS . 82 CHARON-AXP for Linux configuration details . 86 General Settings . 87 Core Devices . 95 Console . 115 Placement of peripheral devices on PCI bus . 121 PBXDA PCI serial lines adapter . 159 Disks and tapes . 162 KZPBA PCI SCSI adapter . 163 KGPSA-CA PCI Fibre Channel adapter . 172 Acer Labs 1543C IDE/ATAPI CD-ROM adapter . 188 PCI I/O Bypass controller . 190 Finding the target "/dev/sg" device . 197 Networking . 199 AlphaStation Sound Card (AD1848) emulation . 206 Sample configuration files . 207 HP AlphaServer 800 configuration file . 208 HP AlphaServer 4000 configuration file . 215 HP AlphaServer DS20 configuration file . 222 HP AlphaServer ES40 configuration file . 229 HP AlphaServer GS80 configuration file . 236 CHARON-AXP for Linux deinstallation . 243 Appendixes . 244 glibc.i686 installation without Internet connection . 245 How to implement time synchronisation between CHARON-AXP Host OS and Guest OS . 249 2 / 255 Document number: 60-16-034-001 Introduction Table of Contents General Description The principles of HP Alpha Hardware Virtualization Virtualized hardware Host platform General Description HP Alpha Hardware Virtualization allows users of HP Alpha (Previously known as DIGITAL Alpha) computers to move application software and user data to a modern Intel or AMD based x64 compatible platform without having to make changes to software and data. -

Way of the Ferret: Finding and Using Resources on the Internet

W&M ScholarWorks School of Education Books School of Education 1995 Way of the Ferret: Finding and Using Resources on the Internet Judi Harris College of William & Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/educationbook Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Judi, "Way of the Ferret: Finding and Using Resources on the Internet" (1995). School of Education Books. 1. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/educationbook/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Education Books by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOCUMENT RESUME IR 018 778 ED 417 711 AUTHOR Harris, Judi TITLE Way of the Ferret: Finding andUsing Educational Resources on the Internet. SecondEdition. Education, Eugene, INSTITUTION International Society for Technology in OR. ISBN ISBN-1-56484-085-9 PUB DATE 1995-00-00 NOTE 291p. Education, Customer AVAILABLE FROM International Society for Technology in Service Office, 480 Charnelton Street,Eugene, OR 97401-2626; phone: 800-336-5191;World Wide Web: http://isteonline.uoregon.edu (members: $29.95,nonmembers: $26.95). PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Guides -Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. Mediated DESCRIPTORS *Computer Assisted Instruction; Computer Communication; *Educational Resources;Educational Technology; Electronic Mail;Information Sources; Instructional Materials; *Internet;Learning Activities; Telecommunications; Teleconferencing IDENTIFIERS Electronic Resources; Listservs ABSTRACT This book is designed to assist educators'exploration of the Internet and educational resourcesavailable online. An overview lists the five basic types of informationexchange possible on the Internet, and outlines five corresponding telecomputingoptions. -

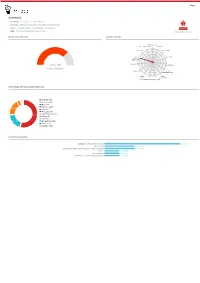

Advanced File Analysis System | Valkyrie

Page 1 Summary File Name: Packing_list_and_Draft_BL.exe File Type: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows SHA1: 948482095bade1c1d72cda2a08b165a47ca128f3 MALWARE MD5: 7828dd5b474006b86ffe30dce57520bc Valkyrie Final Verdict DETECTION SECTION CLASSIFICATION Backdoor(1.74%) Ransomware(0.00%) Bot(0.60%) 81% Worm(3.46%) Exploit(0.00%) 65% 48% Trojan 32% Pua(5.26%) Password Stealer(75.74%) 16% Rootkit(0.00%) Trojan Severity: High Generic(3.43%) Verdict: Malware Spyware(0.00%) Trojan Downloader(4.23%) Remote Trojan Access Dropper(3.60%) Trojan(0.00%V)irus(0.77%) Rogue(1.17%) HIGH LEVEL BEHAVIOR DISTRIBUTION Network (19) Process (128) Misc (47) System (1493) 18.2% Crypto (12) Threading (7) Synchronization (6) 54.0% Device (2) Windows (1) 19.7% File System (543) Services (3) Registry (502) ACTIVITY OVERVIEW Stealing of Sensitive Information 5 (41.67%) Networking 2 (16.67%) Hooking and other Techniques for Hiding Protection 2 (16.67%) Packer 1 (8.33%) Static Anomaly 1 (8.33%) Persistence and Installation Behavior 1 (8.33%) Page 2 Activity Details NETWORKING HTTP traffic contains suspicious features which may be indicative of malware related traffic Show sources Performs some HTTP requests Show sources PACKER The binary likely contains encrypted or compressed data. Show sources STEALING OF SENSITIVE INFORMATION Collects information to fingerprint the system Show sources Steals private information from local Internet browsers Show sources Harvests information related to installed instant messenger clients Show sources Harvests credentials -

Intel Open Network Platform Server Reference Architecture

Intel® Open Network Platform Server Reference Architecture (Version 1.1) NFV/SDN Solutions with Intel® Open Network Platform Server Revision 1.1 September 2014 LEGAL By using this document, in addition to any agreements you have with Intel, you accept the terms set forth below. You may not use or facilitate the use of this document in connection with any infringement or other legal analysis concerning Intel products described herein. You agree to grant Intel a non-exclusive, royalty-free license to any patent claim thereafter drafted which includes subject matter disclosed herein. INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED IN CONNECTION WITH INTEL PRODUCTS. NO LICENSE, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, BY ESTOPPEL OR OTHERWISE, TO ANY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS IS GRANTED BY THIS DOCUMENT. EXCEPT AS PROVIDED IN INTEL'S TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE FOR SUCH PRODUCTS, INTEL ASSUMES NO LIABILITY WHATSOEVER AND INTEL DISCLAIMS ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTY, RELATING TO SALE AND/OR USE OF INTEL PRODUCTS INCLUDING LIABILITY OR WARRANTIES RELATING TO FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, MERCHANTABILITY, OR INFRINGEMENT OF ANY PATENT, COPYRIGHT OR OTHER INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT. A “Mission Critical Application” is any application in which failure of the Intel Product could result, directly or indirectly, in personal injury or death. SHOULD YOU PURCHASE OR USE INTEL'S PRODUCTS FOR ANY SUCH MISSION CRITICAL APPLICATION, YOU SHALL INDEMNIFY AND HOLD INTEL AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES, SUBCONTRACTORS AND AFFILIATES, AND THE DIRECTORS, OFFICERS, AND EMPLOYEES OF EACH, HARMLESS AGAINST ALL CLAIMS COSTS, DAMAGES, AND EXPENSES AND REASONABLE ATTORNEYS' FEES ARISING OUT OF, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, ANY CLAIM OF PRODUCT LIABILITY, PERSONAL INJURY, OR DEATH ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF SUCH MISSION CRITICAL APPLICATION, WHETHER OR NOT INTEL OR ITS SUBCONTRACTOR WAS NEGLIGENT IN THE DESIGN, MANUFACTURE, OR WARNING OF THE INTEL PRODUCT OR ANY OF ITS PARTS. -

The Baylor Lariat Vol

ROUNDING UP CAMPUS NEWS SINCE 1900 THE BAYLOR LARIAT VOL. 109 No. 12 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2009 © 2009, Baylor University Greener Days Bears On Ice Blast Off Club sounds off The club hockey Oldest man to on air quality team starts their space speaks season Sunday and visits BU PAGE 6 PAGE 9 PAGE 4 PAGE 9 TODAY IN PRINT H1N1 claims 99 percent of Texas cases • RESEARCH PROGRESS Center thriving after 2 BY LENA WATERS that we typically see in January It has now been established Wednesday, Dr. Stern said that with flu symptoms on Sept 10. years of existence REPO R TE R and February of each year,” said that the predominate strain of while there have been a few “The doctor asked me what Dr. Sharon Stern, medical direc- flu in Texas is H1N1. cases of H1N1 on campus, there my symptoms were and then PAGE 6 While reports of flu-like ill- tor of Student Health Services in “For Texas, 99 percent have not been as many cases of just to be on the safe side they •GLOBAL THINKING nesses in McLennan County an e-mail to students Thursday of what has been confirmed the flu in general as during reg- did a flu test. She came back and jumped more than 650 percent afternoon. through the Centers for Disease ular flu season. handed me a mask to wear,” Network active in global to 1,494 cases last week, Bay- But with seasonal flu not Control has been H1N1, so we However, Craine said that Clay said. -

Ethical Hacking and Countermeasures

EC-Council | Press The Experts: EC-Council EC-Council’s mission is to address the need for well educated and certifi ed information security and e-business practitioners. EC-Council is a global, member based organization comprised of hundreds of industry and subject matter experts all working together to set the standards and raise the bar in Information Security certifi cation and education. EC-Council certifi cations are viewed as the essential certifi cations needed where standard confi guration and security policy courses fall short. Providing a true, hands-on, tactical approach to security, individuals armed with the knowledge disseminated by EC-Council programs are securing networks around the world and beating the hackers at their own game. The Solution: EC-Council Press The EC-Council | Press marks an innovation in academic text books and courses of study in information security, computer forensics, disaster recovery, and end-user security. By repurposing the essential content of EC-Council’s world class professional certifi cation programs to fi t academic programs, the EC-Council | Press was formed. With 8 Full Series, comprised of 27 different books, the EC-Council | Press is set to revolutionize global information security programs and ultimately create a new breed of practitioners capable of combating this growing epidemic of cybercrime and the rising threat of cyber war. This Certifi cation: C|EH – Certifi ed Ethical Hacker Certifi ed Ethical Hacker is a certifi cation designed to immerse the learner in an interactive environment where they will learn how to scan, test, hack and secure information systems. Ideal candidates for the C|EH program are security professionals, site administrators, security offi cers, auditors or anyone who is concerned with the integrity of a network infrastructure. -

Malicious Activity Report: Elements of Lokibot Infostealer

Malicious Activity Report: Elements of Lokibot Infostealer Author: Minh Hoang Executive Summary This paper presents the results and finding of our analysis of the behavior, techniques, targets, and unpacking methods of a Lokibot information stealer sample. We were able to uncover features that can be utilized to prevent and mitigate the threat. We conducted dynamic and static analyses. Our dynamic analysis showed Lokibot’s behavior, including the benefits and drawbacks of several unpacking methods. We also analyzed how Lokibot avoided repeat execution, how it (unsuccessfully attempted to achieved persistence, and provided a list of applications that Lokibot will use to search for credentials on a victim’s system. Lokibot Threat Characteristics Lokibot is a malware designed to collect credentials and security tokens from an infected machine running on a Windows Operating System (OS). Lokibot was first observed in 2015, when it targeted cryptocoin wallets, though there is evidence that the widely-spread version was a hijacked version (also referred to as patched or cracked version) of the earlier one. One of the key differences is that the patched version allows the attacker to change the command and control (C2) URL.1 Once executed, Lokibot unpacks the main binary into memory using hollow process injection2 to insert itself into a legitimate Microsoft Windows application to hide its activities. Lokibot also used an infected system machine global unique identifier (GUID) value to generate a mutex (an MD5 hash) that acted as a flag to prevent itself from infecting the same machine again. Lokibot collects information and credentials from multiple applications, including but not limited to Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Thunderbird, FTP and SFTP applications. -

Automated Scheduling for NASA's Deep Space Network

Articles Automated Scheduling for NASA’s Deep Space Network Mark D. Johnston, Daniel Tran, Belinda Arroyo, Sugi Sorensen, Peter Tay, Butch Carruth, Adam Coffman, Mike Wallace n This article describes the Deep Space Net - ASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) provides commu - work (DSN) scheduling engine (DSE) compo - nications and other services for planetary explo - nent of a new scheduling system being ration missions as well as other missions beyond geo - deployed for NASA’s Deep Space Network. The N stationary orbit, supporting both NASA and international DSE provides core automation functionality users. It also constitutes a scientific facility in its own right, for scheduling the network, including the interpretation of scheduling requirements conducting radar investigations of the moon and planets, in expressed by users, their elaboration into addition to radio science and radio astronomy. The DSN tracking passes, and the resolution of conflicts comprises three antenna complexes in Goldstone, Califor - and constraint violations. The DSE incorpo - nia; Madrid, Spain; and Canberra, Australia. Each complex rates both systematic search- and repair- contains one 70 meter antenna and several 34 meter anten - based algorithms, used for different phases nas (figure 1), providing S-, X-, and K-band up- and down - and purposes in the overall system. It has link services. The distribution in longitude enables full sky been integrated with a web application that coverage and generally provides some overlap in spacecraft provides DSE functionality to all DSN users through a standard web browser, as part of a visibility between the complexes. A more detailed discussion peer-to-peer schedule negotiation process for of the DSN and its large antennas can be found in the paper the entire network. -

Conference Schedule View the Full Lineup Of

Sessions at a Glance 8:30 – 8:50 AM Welcome and Dean Metzger’s Opening Remarks (Welcome Zoom Room) David Metzger, Dean of Perry Honors College 8:45 – 9:00 AM Presenter Check-in 9:00 – 9:55 AM Session 1. pp. 9-12 Interdisciplinary Research #1 [3 presentations] (Zoom Room A) Room Moderator: Chunqi Jiang & Kristen Eggler 1. Elizabeth Harden. A Qualitative Study of Representations of Socially Stigmatized Individuals in CSI 2. Torre Williams, Cesar Ariel. Pinto Fundamentals of Human- Centric Artificial Intelligence (A.I): Comparative Analysis of Europe and the U.S. Landscape 3. Kyle Canady, Jian Wu. Extracting Datasets, methods, and projects for ACL Anthology Papers College of Sciences UG Research #1 (Zoom Room B) Room Moderator: Desmond Cook 1. Q&A for COS Students interested in UGR Monarchs Maximizing Access to Research Careers #1: (Zoom Room C) Room Moderator: Alvin Holder & Desh Ranjan Info Session Art Exhibit Video (Zoom Room D) Room Moderators: Tamara Dunn & Elliott Jones 1. Continuous Art Show Loop of Video INNOVATE Panel: (Zoom Room E) Room Moderators: Leona Mcgowan & Jennifer Grimm 1. Kayla Marbella 2. Ashanti Cameron Coastal and Estuarine Science [3 presentations] (Zoom Room F) Room Moderators: Sophie Clayton & Michala Hendrick 1. Alexander Burns, Alexander Bitterman, Tim Muraskin, Autumn Kistler, Jennifer Huggins, Christopher Zajchowski. Visitor Motivations and Public Health Perceptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study from First Landing State Park 2. Kayla Marciniak, Chanel Flores-Vargas, Kathryn M. Wiesner, Leah Gibala-Smith, Sophie Clayton. Direct observations of the life cycle of Heterocapsa triquetra in the Elizabeth River. 3. -

(PEPSSI) on the New Horizons Mission

The Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI) on the New Horizons Mission Ralph L. McNutt, Jr.1,6, Stefano A. Livi2, Reid S. Gurnee1, Matthew E. Hill1, Kim A. Cooper1, G. Bruce Andrews1, Edwin P. Keath3, Stamatios M. Krimigis1,4, Donald G. Mitchell1, Barry Tossman3, Fran Bagenal5, John D. Boldt1, Walter Bradley3, William S. Devereux1, George C. Ho1, Stephen E. Jaskulek1, Thomas W. LeFevere1, Horace Malcom1, Geoffrey A. Marcus1, John R. Hayes1, G. Ty Moore1, Bruce D. Williams, Paul Wilson IV3, L. E. Brown1, M. Kusterer1, J. Vandegriff1 1The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 11100 Johns Hopkins Road, Laurel, MD 20723, USA 2Southwest Research Institute, 6220 Culebra Road, San Antonio, TX 78228, USA 3The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, retired 4 Academy of Athens, 28 Panapistimiou, 10679 Athens, Greece 5The University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA 6443-778-5435, 443-778-0386, [email protected] The Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI) comprises the hardware and accompanying science investigation on the New Horizons spacecraft to measure pick-up ions from Pluto’s outgassing atmosphere. To the extent that Pluto retains its characteristics similar to those of a “heavy comet” as detected in stellar occultations since the early 1980s, these measurements will characterize the neutral atmosphere of Pluto while providing a consistency check on the atmospheric escape rate at the encounter epoch with that deduced from the atmospheric structure at lower altitudes by the ALICE, REX, and SWAP experiments on New Horizons. In addition, PEPSSI will characterize any extended ionosphere and solar wind interaction while also characterizing the energetic particle environment of Pluto, Charon, and their associated system.