Reduction” of the Marianas Resettlement Into Villages Under the Spanish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CNMI Workers' Compensation Program Was Created by the Enactment of Senate Bill 6-54 Into Public Law 6-33, the CNMI Workers' Compensation Law

What You Need To Know About The CNMI Workers’ Compensation Program A Handbook For, Employers, Carriers and Employees Department of Commerce Workers’ Compensation Commission Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands About This Handbook This handbook is prepared to highlight some of the major provisions of the Workers' Compensation law, rules and regulations and to provide the users pertinent information and answers. Since this handbook provides only highlights which may not fully explain the law, it is strongly recommended that you read the law, coded under Title 4, Division 9, Chapter 3, of the Commonwealth Code. The handbook is divided into seven (7) major sections: 1) The Brief Information section which defines the purpose of the program. 2) Employer/Carrier section which covers essential information for the employer and carrier. 3) The Employee section provides the highlights regarding employee's right and responsibilities and the type of benefits. 4) The Claims procedure section discusses the how to obtain benefits for job related injury, illness or death. 5) The Adjudication section describes the settlement of disputes. 6) The Notices section describes the various forms used and deadlines. 7) Penalties section describes the penalties for violation of law. Employees are encouraged to discuss their responsibilities fully with supervisors to avoid the likelihood of missing deadlines and reports and consequently benefits. Remember, it is your responsibility to prove that your injury is work-related. For more information, please contact the Department of Commerce Workers' Compensation Office nearest you: Saipan: Tinian Rota Department of Commerce Department of Commerce Department of Commerce Workers’ Compensation Commission Workers’ Compensation Commission Workers’ Compensation Commission P.O. -

Visual/Media Arts

A R T I S T D I R E C T O R Y ARTIST DIRECTORY (Updated as of August 2021) md The Guam Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency (GCAHA) has produced this Artist Directory as a resource for students, the community, and our constituents. This Directory contains names, contact numbers, email addresses, and mailing or home address of Artists on island and the various disciplines they represent. If you are interested in being included in the directory, please call our office at 300-1204~8/ 7583/ 7584, or visit our website (www.guamcaha.org) to download the Artist Directory Registration Form. TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCIPLINE PAGE NUMBER FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS 03 - 17 VISUAL/ MEDIA ARTS 18 - 78 PERFORMING ARTS 79 - 89 LITERATURE/ HUMANITIES 90 - 96 ART RELATED ORGANIZATIONS 97 – 100 MASTER’S 101 - 103 2 FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS Folk Arts enriches the lives of the Guam community, gives recognition to the indigenous and ethnic artists and their art forms and to promote a greater understanding of Guam’s native and multi-ethnic community. Ronald Acfalle “ Halu’u” P.O. BOX 9771 Tamuning, Guam 96931 [email protected] 671-689-8277 Builder and apprentice of ancient Chamorro (seafaring) sailing canoes, traditional homes and chanter. James Bamba P.O. BOX 26039 Barrigada, Guam 96921 [email protected] 671-488-5618 Traditional/ Contemporary CHamoru weaver specializing in akgak (pandanus) and laagan niyok (coconut) weaving. I can weave guagua’ che’op, ala, lottot, guaha, tuhong, guafak, higai, kostat tengguang, kustat mama’on, etc. Arisa Terlaje Barcinas P.O.BOX 864 Hagatna, Guam 96932 671-488-2782, 671-472-8896 [email protected] Coconut frond weaving in traditional and contemporary styles. -

Chapter 8. Land and Submerged Lands Use

Guam and CNMI Military Relocation Draft EIS/OEIS (November 2009) CHAPTER 8. LAND AND SUBMERGED LANDS USE 8.1 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 8.1.1 Definition of Resource This chapter describes and analyzes impacts of the proposed action on land and submerged lands ownership and management, and land and submerged lands use. Submerged lands refer to coastal waters extending from the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) coastline into the ocean 3 nautical miles (nm) (5.6 kilometers [km]), the limit of state or territorial jurisdiction. Land use discussions for this Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement (EIS/OEIS) include civilian and military existing and planned land uses, and land use planning guidance that directs future development. With respect to land ownership on Tinian, fee interest ownership is the primary means of private land ownership; leases or easements may also be used for land transfer or management purposes. On Tinian, the Department of Defense (DoD) leases approximately two-thirds of the total island area, exerting a notable influence upon Tinian land use. This chapter is organized to first look at existing conditions, then impacts are identified by alternatives and components. The chapter concludes with identification and discussion of potential mitigation measures that apply to significant impacts. The region of influence (ROI) for land use is land and submerged lands of Tinian. The proposed action is limited to Tinian; therefore, the emphasis is on Tinian with background information provided on CNMI. 8.1.2 Tinian Article XI and XII of the CNMI Constitution states that public lands collectively belong to the people of the Commonwealth who are of Northern Marianas decent. -

Bus Schedule Carmel Catholic School Agat and Santa Rita Area to Mount Bus No.: B-39 Driver: Salas, Vincent R

BUS SchoolSCHEDULE Year 2020 - 2021 Dispatcher Bus Operations - 646-3122 | Superintendent Franklin F. Tait ano - 646-3208 | Assistant Superintendent Daniel B. Quintanilla - 647-5025 THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUS OPERATIONS REQUIRES ALL STUDENTS TO WEAR A MASK PRIOR TO BOARDING THE BUS. THERE WILL BE ONE CHILD PER SEAT FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING. PLEASE ANTICIPATE DELAYS IN PICK UP AND DROP OFF AT DESIGNATED BUS SHELTERS. THANK YOU. TENJO VISTA AND SANTA RITA AREAS TO O/C-30 Hanks 5:46 2:29 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL O/C-29 Oceanview Drive 5:44 2:30 A-2 Tenjo Vista Entrance 7:30 4:01 O/C-28 Nimitz Hill Annex 5:40 2:33 A-3 Tenjo Vista Lower 7:31 4:00 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:15 1:50 AGAT A-5 Perez #1 7:35 3:56 PAGACHAO AREA TO MARCIAL SABLAN DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. A-14 Lizama Station 7:37 3:54 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (A.M. ONLY) BUS NO.: B-123 A-15 Borja Station 7:38 3:53 SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:00 A-16 Naval Magazine 7:39 3:52 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:10 STATION LOCATION NAME PICK UP DROP OFF A-17 Sgt. Cruz 7:40 3:51 A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-18 M & R Store 7:41 3:50 PAGACHAO AREA TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 SCHOOL A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-19 Annex 7:42 3:49 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-20 Rapolla Station 7:43 3:48 A-46 Round Table 7:15 3:45 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:50 3:30 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:22 3:53 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 A-37 Pagachao Lower 7:25 3:50 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 HARRY S. -

Report on Northern Mariana Islands Workforce Act of 2018, U.S. Public

U.S. Department of the Interior Report to Congress Technical Assistance Northern Mariana Islands U.S. Workforce Act of 2018 October 2019 Department of the Interior TABLE OF CONTENTS Report of the Secretary of the Interior on Immigration in the CNMI 2 Office of Insular Affairs Authorities and Responsibilities to the Territories 2 Technical Assistance Program 3 Capital Improvement Project 3 Energizing Island Communities 4 Background and History of the CNMI Economy 5 Typhoon Yutu 7 Activities to Identify Opportunities for Economic Growth and Diversification 8 Office of Insular Affairs: Technical Assistance 8 Department of Commerce 11 International Trade Administration 11 Bureau of Economic Analysis 12 U.S. Census Bureau 12 Economic Development Administration 13 Office of Insular Affairs: Recruiting, Training, and Hiring U.S. Workers 14 Department of Labor 15 Background and Foreign Labor Certification 15 Implementation of Workforce Act 15 Commonwealth Worker Fund Annual Plan 16 Office of Insular Affairs: Technical Assistance 16 U.S. Department of Labor Formula and Discretionary Grants 17 Other Technical Assistance and Consultation 18 Section 902 Consultation of the Revocation of the PRC Tourist Parole Program 18 Recommendations by the Special Representatives 19 Conclusion 19 REPORT OF THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR ON RESPONSIBILITIES TO THE COMMONWEALTH OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS In July 2018, President Trump signed into law H.R. 5956, the Northern Mariana Islands U.S. Workforce Act of 2018 (Act or the Workforce Act), Public Law 115-218. -

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Coastal Resilience Assessment

COMMONWEALTH OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS COASTAL RESILIENCE ASSESSMENT 20202020 Greg Dobson, Ian Johnson, Kim Rhodes UNC Asheville’s NEMAC Kristen Byler National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Bridget Lussier Lynker, on contract to NOAA Office for Coastal Management IMPORTANT INFORMATION/DISCLAIMER: This report represents a Regional Coastal Resilience Assessment that can be used to identify places on the landscape for resilience-building efforts and conservation actions through understanding coastal flood threats, the exposure of populations and infrastructure have to those threats, and the presence of suitable fish and wildlife habitat. As with all remotely sensed or publicly available data, all features should be verified with a site visit, as the locations of suitable landscapes or areas containing flood threats and community assets are approximate. The data, maps, and analysis provided should be used only as a screening-level resource to support management decisions. This report should be used strictly as a planning reference tool and not for permitting or other legal purposes. The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government, or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s partners. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation or its funding sources. NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DISCLAIMER: The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of NOAA or the Department of Commerce. -

(L7*~2A-, JOSEPH F

LC**A. CLAM U 5 A October 25. 1989 The Honorable Joe T. San Agustin Speaker, Twentieth Guam Legislature Post Off ice Box CB-1 Agana. Guam 969 10 Oesr Mr. Speaker: Transmitted herewith is Bill No. 994. which 1 have signed into Isw this date as Public Law 20-1 14, Si erety, (L7*~2a-, JOSEPH F. ADA Governor Enclosure TWENTIETH GUAM LEGISLATURE 1989 (FIRST) Rephr Session- --- ---a= CERTIFICATION OF PASSAGE OF AN ACT TO THE GOVERNOR This is to certify that Substitute Bill No. 994 (LS), "AN ACT TC APPROPRIATE FUNDS FROM THE GENERAL FUND TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS TO REPAIR AND CORRECT THE FLOODING DAMAGE CAUSED BY TROPICAL STORM COLLEEN, TO CORRECT A PREVIOUS APPROPRIATION, AND TO AUTHORIZE PRIVATE TELEPHONES AT GUAM MEMORIAL HOSPITAL FOR RELATIVES1 USE," was on the 16th day 01 October, 1989, duly and regularly passed. Attested : Senator and ~e~islativeSecretary This Act was received by the C-vernor this 30% day of h&. 1989. at -+:% o'clock Governor's Office APPROVED : n / h'. AUA 1 Governor of Guam / Date: October 25. 1989 Public Law-No. 20-114 163 Chalcrn Sonto Papa Street Agono, Gwm969 10 STATEMENT OF THE SPEAKER I hereby certify, pursuant to $2103 of Title 2 of the Guam Code Annotated, that emergency condftfons exist involving dari~erto ti16 public health and safety due to the serious flmding ant! cther damage ctused by Tropical Stom Colleen, and the potentlal similar harm from other tropical storms during this typhoon season. 1 hereby waive the requirement for a public hearing on Bill 170. -

View on KKMP This Morning

Super Typhoon Yutu Relief & Recovery Update #4 POST-DECLARATION DAMAGE ASSESSMENT COMPLETED; RELIEF MANPOWER ON-ISLAND READY TO SUPPORT; FEEDER 1, PARTIAL 1 & 2 BACK ONLINE Release Date: October 29, 2018 On Sunday, October 28, 2018, CNMI Leadership and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) conducted a Post-Declaration Damage Assessment. Saipan, Tinian and Rota experienced very heavy rainfall and extremely high winds which caused damages to homes, businesses and critical infrastructure. Utility infrastructure on all three islands has been visibly severely impacted to include downed power lines, transformers and poles. Driving conditions remain hazardous as debris removal operations are still underway. At the request of Governor Ralph DLG. Torres, representatives from FEMA Individual Assistance (IA) and the US Small Business Administration (SBA) joined the CNMI on an Aerial Preliminary Damage Assessment of Saipan, Tinian and Rota. Findings are as follows: SAIPAN: 317 Major; 462 Destroyed (T=779) Villages covered: Kagman 1, 2 & 3 and LauLau, Susupe, Chalan Kanoa, San Antonio, Koblerville, Dandan and San Vicente Power outage across the island 2-mile-long gas lines observed Extensive damage to critical infrastructure in southern Saipan Downed power poles and lines Page 1 of 8 Page printed at fema.gov/ja/press-release/20201016/super-typhoon-yutu-relief-recovery-update-4-post-declaration- 09/28/2021 damage TINIAN: 113 Major; 70 Destroyed (T=183) Villages covered: San Jose & House of Taga, Carolinas, Marpo Valley and Marpo Heights Power outage across the island; estimated to take 3 months to achieve 50% restoration Tinian Health Center sustained extensive damage Observed a downed communications tower ROTA: 38 Major; 13 Destroyed (T=51) Villages covered: Songsong Village and Sinapalo Power outage across the island Sustained the least amount of damage as compared to Saipan and Tinian Red Cross CNMI-wide assessments begin Tuesday, October 30, 2018. -

Freshwater Use Customs on Guam an Exploratory Study

8 2 8 G U 7 9 L.I:-\'I\RY INT.,NATIONAL R[ FOR CO^.: ^,TY W SAMIATJON (IRC) FRESHWATER USE CUSTOMS ON GUAM AN EXPLORATORY STUDY Technical Report No. 8 iei- (;J/O; 8;4J ii ext 141/142 LO: FRESHWATER USE CUSTOMS ON AN EXPLORATORY STUDY Rebecca A. Stephenson, Editor UNIVERSITY OF GUAM Water Resources Research Center Technical Report No. 8 April 1979 Partial Project Completion Report for SOCIOCULTURAL DETERMINANTS OF FRESHWATER USES IN GUAM OWRT Project No. A-009-Guam, Grant Agreement Nos. 14-34-0001-8012,9012 Principal Investigator: Rebecca A- Stephenson Project Period: October 1, 1977 to September 30, 1979 The work upon which this publication is based was supported in part by funds provided by the Office of Water Research and Technology, U. S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C, as authorized by the Water Research and Development Act of 1978. T Contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Office of Water Research and Technology, U. S. Department of the Interior, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute their endorsement or recommendation for use by the U- S. Government. ii ABSTRACT Traditional Chamorro freshwater use customs on Guam still exist, at least in the recollections of Chamorros above the age of 40, if not in actual practice in the present day. Such customs were analyzed in both their past and present contexts, and are documented to provide possible insights into more effective systems of acquiring and maintain- ing a sufficient supply of freshwater on Guam. -

Download This Volume

Photograph by Carim Yanoria Nåna by Kisha Borja-Quichocho Like the tåsa and haligi of the ancient Chamoru latte stone so, too, does your body maintain the shape of the healthy Chamoru woman. With those full-figured hips features delivered through natural birth for generations and with those powerful arms reaching for the past calling on our mañaina you have remained strong throughout the years continuously inspire me to live my culture allow me to grow into a young Chamoru woman myself. Through you I have witnessed the persistence and endurance of my ancestors who never failed in constructing a latte. I gima` taotao mo`na the house of the ancient people. Hågu i acho` latte-ku. You are my latte stone. The latte stone (acho` latte) was once the foundation of Chamoru homes in the Mariana Islands. It was carved out of limestone or basalt and varied in size, measuring between three and sixteen feet in height. It contained two parts, the tasa (a cup-like shape, the top portion of the latte) and the haligi (the bottom pillar) and were organized into two rows, with three to seven latte stones per row. Today, several latte stones still stand, and there are also many remnants of them throughout the Marianas. Though Chamorus no longer use latte stones as the foundations of their homes, the latte symbolize the strength of the Chamorus and their culture as well as their resiliency in times of change. Micronesian Educator Editor: Unaisi Nabobo-Baba Special Edition Guest Editors: Michael Lujan Bevacqua Victoria Lola Leon Guerrero Editorial Board: Donald Rubinstein Christopher Schreiner Editorial Assistants: Matthew Raymundo Carim Yanoria Design and Layout: Pascual Olivares ISSN 1061-088x Published by: The School of Education, University of Guam UOG Station, Mangilao, Guam 96923 Contents Guest Editor’s Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

Quarterly Web Report FY 2016 (Start 10-01

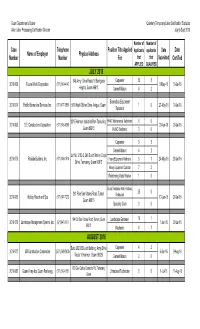

Guam Department of Labor Quarterly Temporary Labor Certification Statistics Alien Labor Processing Certification Division July to Sept 2016 Number of Number of Case Telephone Position Title Applied Applicants applicants Date Date Name of Employer Physical Address Number Number For that that Submitted Certified APPLIED QUALIFIED JULY 2016 945 Army Drive Route 16 Barrigada Carpenter 12 8 2016-069 Future World Corporation (671) 649-4147 5-May-16 19-Jul-16 Heights, Guam 96913 Cement Mason 4 2 Biomedical Equipment 2016-074 Pacific Biomedical Services, Inc. (671) 477-0566 587 West O'Brien Drive, Anigua, Guam 1 0 23-May-16 19-Jul-16 Specialist 201E Harmon Industrial Park Tamuning, HVAC Maintenance Technician 6 0 2016-065 S.E. Construction Corporation (671) 646-9098 29-Apr-16 26-Jul-16 Guam 96913 HVAC Mechanic 3 0 Carpenter 5 3 Cement Mason 4 2 Lot No. 2102-2, 246 South Marine Corps 2016-075 Reliable Builders, Inc. (671) 646-1516 Heavy Equipment Mechanic 5 1 24-May-16 28-Jul-16 Drive, Tamuning, Guam 96913 Heavy Equipment Operator 7 3 Reinforcing Metal Worker 1 0 Guest Relations Host/ Hostess, 881 Pale San Vitores Road, Tumon 25 0 2016-080 Holiday Resort and Spa (671) 647-7272 Restaurant 13-Jun-16 28-Jul-16 Guam 96913 Specialty Cook 0 0 194 Old San Vitores Road, Tumon, Guam Landscape Gardener 16 1 2016-076 Landscape Management Sytems, Inc. (671)647-2617 1-Jun-16 28-Jul-16 96913 Mechanic 4 1 AUGUST 2016 Suite 202/203 Lee's Building, Army Drive Carpenter 4 2 2016-077 5M Construction Corporation (671) 648-3435 6-Jun-16 9-Aug-16 Route 16 Harmon, Guam 96929 Cement Mason 2 0 633 Gov.Carlos Camacho Rd. -

CHAMORRO CULTURAL and RESEARCH CENTER Barbara Jean Cushing

CHAMORRO CULTURAL AND RESEARCH CENTER Barbara Jean Cushing December 2009 Submitted towards the fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Architecture degree. University of Hawaii̒ at Mānoa School of Architecture Spencer Leineweber, Chairperson Joe Quinata Sharon Williams Barbara Jean Cushing 2 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center Chamorro Cultural and Research Center Barbara Jean Cushing December 2009 ___________________________________________________________ We certify that we have read this Doctorate Project and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Architecture in the School of Architecture, University of Hawaii̒ at Mānoa. Doctorate Project Committee ______________________________________________ Spencer Leineweber, Chairperson ______________________________________________ Joe Quinata ______________________________________________ Sharon Williams Barbara Jean Cushing 3 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center CONTENTS 04 Abstract phase 02 THE DESIGN 08 Field Of Study 93 The Next Step 11 Statement 96 Site Analysis 107 Program phase 01 THE RESEARCH 119 Three Concepts 14 Pre‐Contact 146 The Center 39 Post‐Contract 182 Conclusion 57 Case Studies 183 Works Sited 87 ARCH 548 186 Bibliography Barbara Jean Cushing 4 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center ABSTRACT PURPOSE My architectural doctorate thesis, titled ‘Chamorro Cultural and Research Center’, is the final educational work that displays the wealth of knowledge that I have obtained throughout the last nine years of my life. In this single document, it represents who I have become and identifies the path that I will be traveling in the years to follow. One thing was for certain when beginning this process, in that Guam and my Chamorro heritage were to be important components of the thesis.