Charles-Édouard Jeanneret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Corbusier Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris

Le Corbusier Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris Portrait on Swiss ten francs banknote Personal information Name: Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris Nationality: Swiss / French Birth date: October 6, 1887 Birth place: La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland Date of death: August 27, 1965 (aged 77) Place of death: Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France 1 Created with novaPDF Printer (www.novaPDF.com). Please register to remove this message. Major buildings and projects The Open Hand Monument is one of numerous projects in Chandigarh, India designed by Le Corbusier 1905 - Villa Fallet, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland 1912 - Villa Jeanneret-Perret, La Chaux-de-Fonds [1] 1916 - Villa Schwob, La Chaux-de-Fonds 1923 - Villa LaRoche/Villa Jeanneret, Paris 1924 - Pavillon de L'Esprit Nouveau, Paris (destroyed) 1924 - Quartiers Modernes Frugès, Pessac, France 1925 - Villa Jeanneret, Paris 1926 - Villa Cook, Boulogne-sur-Seine, France 1927 - Villas at Weissenhof Estate, Stuttgart, Germany 1928 - Villa Savoye, Poissy-sur-Seine, France 1929 - Armée du Salut, Cité de Refuge, Paris 1930 - Pavillon Suisse, Cité Universitaire, Paris 1930 - Maison Errazuriz, Chile 1931 - Palace of the Soviets, Moscow, USSR (project) 1931 - Immeuble Clarté, Geneva, Switzerland 1933 - Tsentrosoyuz, Moscow, USSR 1936 - Palace of Ministry of National Education and Public Health, Rio de Janeiro 1938 - The "Cartesian" sky-scraper (project) 1945 - Usine Claude et Duval, Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, France 1947-1952 - Unité d'Habitation, Marseille, France 1948 - Curutchet House, La Plata, Argentina 1949-1952 - United Nations headquarters, New York City (project) 1950-1954 - Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, France 1951 - Cabanon Le Corbusier, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin 2 Created with novaPDF Printer (www.novaPDF.com). -

Le Corbusier Y El Salon D' Automne De París. Arquitectura Y

Le Corbusier y el Salon d’ Automne de París. Arquitectura y representación, 1908-1929 José Ramón Alonso Pereira “Arquitectura y representación” es un tema plural que abarca tanto la figuración como la manifestación, Salón d’ Automne imagen y escenografía de la arquitectura. Dentro de él, se analiza aquí cómo Le Corbusier plantea una interdependencia entre la arquitectura y su imagen que conlleva no sólo un nuevo sentido del espacio, sino Le Corbusier también nuevos medios de representarlo, sirviéndose de los más variados vehículos expresivos: de la acuarela Équipement de l’habitation al diorama, del plano a la maqueta, de los croquis a los esquemas científicos y, en general, de todos los medios posibles de expresión y representación para dar a conocer sus inquietudes y sus propuestas en un certamen Escala singular: el Salón de Otoño de París; cuna de las vanguardias. Espacio interior Le Corbusier concurrió al Salón d’ Automne con su arquitectura en múltiples ocasiones. A él llevó sus dibujos de Oriente y a él volvió en los años veinte a exhibir sus obras, recorriendo el camino del arte-paisaje a la arquitectura y, dentro de ella -en un orden inverso, anti-clásico-, de la gran escala o escala urbana a la escala edificatoria y a la pequeña escala de los espacios interiores y el amueblamiento. “Architecture and Representation” is a plural theme that includes both figuration as manifestation, image and Salon d’ Automne scenography of architecture. Within it, here it is analyzed how Le Corbusier proposes an interdependence between architecture and image that entails not only a new sense of space, but also new means of representing it, using Le Corbusier the most varied expressive vehicles: from watercolor to diorama, from plans to models, from sketches to scientific Équipement de l’habitation schemes and, in general, using all possible expression and representation means to make known their concerns and their proposals, all of them within a singular contest: the Paris’s Salon d’ Automne; cradle of art avant-gardes. -

Le Corbusier and His Contemporaries

1 April 2002 Art History W36456 Important announcements: Monday April 8th I cannot prepare class ahead of time, we will instead view a series of films by and about Le Corbusier and his contemporaries. To make up for the missed lecture there will be an extra concluding class of the course on Weds. May 8th at the usual time and in this room. Please mark your calendars. As we are now behind the course will conclude with 1965 and the examination will include all material through topic 25. A new course on Post War Architecture, the third part of the survey then, will be introduced in 2003-4. Le Corbusier: Architecture or Revolution (architecture and urbanism to 1930) Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (takes name Le Corbusier in the 1920s) b. 1887 La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, died Roquebrunne (Riveria) 1965; architect in Paris from 1917 on. Arts School in La Chaux de Fonds and influence of Charles L’Eplattenier 1905-06 Villa Fallet, La Chaux de Fonds 1908-9 in Paris with Perret and meets Tony Garnier 1910 with Theodore Fischer in Munich and with Behrens in Berlin/Potsdam 1908 Villa Jacquemet, La Chaux de Fonds 1914-16 Villa Schwob (Maison Turque), La Chaux-de-Fonds (first concrete frame) 1914 Domino (Dom-Ino) project with Max Dubois 1918 publishes Après le Cubisme with Amedée Ozenfant 1920 first issue of the magazine L’Esprit Nouveau 1923 Vers une Architecture (translated into English in 1927 as Towards a new Architecture) 1922 Salone d’Automne Paris, he exhibits the Citrohan House and the Ville de 3 Millions d’Habitants 1922 Ozenfant Studio, Paris -

Le Corbusier Architecture Tour of Switzerland

Le Corbusier architecture tour of Switzerland http://www.travelbite.co.uk/printerfriendly.aspx?itemid=1252859 Le Corbusier architecture tour of Switzerland Friday, 05 Dec 2008 00:00 Considered by many to be the most important architect of the 20th century, Charles- Édouard Jeanneret-Gris – who chose to be known as Le Corbusier – was the driving force behind the International style. Also known as Modern architecture, the movement stressed the importance of form and the elimination of ornament - values explored by Le Corbusier over a career spanning five decades. His Five Points – first expressed in the L'Esprit Nouveau - epitomise the style, and allowed his work to spread from his native Switzerland around the world, including developments in Le Maison Blanche (credit: Eveline France, India, Russia, Chile, Germany and even Iraq. Perroud) Born in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, Le Corbusier began his career in his home town with La Maison Blanche – a very personal project for his parents, completed in 1912. It is one of a number of Le Corbusier buildings still standing in Switzerland, and here travelbite.co.uk takes a look at what is on offer to visitors as they explore his native land. La Chaux-de-Fonds Le Maison Blanche was the first independent project completed by Le Corbusier, and draws on his experience in Paris as a student of Auguste Perret and Peter Behrens in Berlin. Situated in his home town of La Chaux-de-Fonds, guests are invited to explore one of the early works of the aspiring architect, who had not yet taken the name Le Corbusier. -

The Mutual Culture: Le Corbusier and The

The mutual culture: Le Corbusier and the french tradition Autor(es): Linton, Johan Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41610 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-1338-3_7 Accessed : 28-Sep-2021 19:35:38 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Edited byArmando Rabaça Ivan Zaknic Arthur Rüegg L E David Leatherbarrow C ORBUSIER Christoph Schnoor H Francesco Passanti ISTORY Johan Linton Stanislaus von Moos T and Maria Candela Suárez RADITION L E C ORBUSIER and H ISTORY T RADITION Edited by Armando Rabaça 1. -

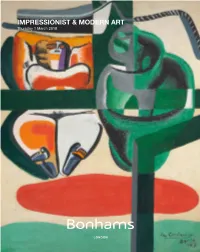

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

The Urban Canvas: Urbanity and Painting in Maison Curutchet

130 ACSA EUROPEANCONFERENCE LISBON HISTORYTTHEORY/CRITIClSM . 1995 The Urban Canvas: Urbanity and Painting in Maison Curutchet ALEJANDRO LAPUNZINA University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign USA ABSTRACT A BRIEF HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF MAISON CURUTCHET This paper proposes a reading of the faqade of Maison Curutchet, a significant yet largely unstudied building de- In September 1948, Dr. Curutchet, a well-knownprogressive signed by Le Corbusier in 1949, as a metaphor or a condenser surgeon from Argentina, contacted Le Corbusier, however of the architect's ideas on urban-planning and painting. It indirectly, requesting his architectural services for the de- also proposes that in this building Le Corbusier proved to be sign of a combination of single family dwelling and medical (contrary to what is often asserted) one of the most contex- office in a site, facing a beautiful large urban park, that he tually urban oriented architects of the twentieth century. owned in the city of La Plata, one-hundred kilometers south of Buenos Aire~.~He sent to Le Corbusier a very detailed program of his needs that included a three- bedroom house INTRODUCTION with all "modern comforts," and an independent medical Maison Curutchet is undoubtedly one of the least known cabinet consisting of waiting room and consultation office buildings designed by Le Corbusier. The reasons for the little where he could perform minor surgical interventions imple- attention that this work received from critics and historians menting his then revolutionary techniques. to-date are manifold, and should be attributed to the building's In spite of being extremely busy with the design and geographical location, far away from what were then the construction of other major projects (most notably the Unite centers of architectural production (the discourse and the d'Habitation in Marseilles and the Masterplan for St. -

10 Franc Banknote: Le Corbusier (Charles Edouard Jeanneret),1887-1965 Architect, Town Planner and Theoretician, Painter, Sculptor and Writer

10 franc banknote: Le Corbusier (Charles Edouard Jeanneret),1887-1965 Architect, town planner and theoretician, painter, sculptor and writer Le Corbusier is regarded as one of the outstanding creative personalities of the twentieth century. He was a universal designer who was active in many fields: as an architect, town planner, painter, sculptor and the author of numerous books on architecture, urban planning and design. Le Corbusier's remarkable ability to communicate his ideas helped to gain recognition for his theories throughout the world. His work is a modern Gesamtkunstwerk that combines individual disciplines into a complex whole. This is particularly apparent in his visionary urban planning projects. Le Corbusier pioneered a quintessentially modern approach to architecture. Urban planning Le Corbusier's concepts of residential building design are based on extensive studies of the social, architectural and urban planning problems of the industrial era. Le Corbusier always placed the human being at the centre of his creative principles. In his book Urbanisme (The City of Tomorrow), published in 1924, and in numerous other studies on this topic, he formulated some of the most important principles of modern urban planning: the city, he wrote, must be planned as an organic whole and designed in spatial terms to support the functions of living, work, recreation, education and transport. One important goal was to separate work and relaxation into spaces that would be experienced separately. Chandigarh (1950 - 1962) Although Le Corbusier was involved in numerous urban planning projects, only two were implemented: Pessac- Bordeaux (1925) and Chandigarh. In this latter project, Le Corbusier received a contract from the government of India in 1950 to build the new capital of the Indian state of Punjab, which was established after the Second World War. -

PDF Download Le Corbusier Redrawn: the Houses

LE CORBUSIER REDRAWN: THE HOUSES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Soojin Park,Steven Park | 192 pages | 07 Nov 2012 | PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS | 9781616890681 | English | New York, United States Le Corbusier Redrawn: The Houses PDF Book Ke Hu rated it really liked it Jul 17, Shivam rated it really liked it Oct 05, Villa Le Lac, Corseaux, Switzerland,; 4. Maisons Weissenhof-Siedlung, Stuttgart, Germany, ; Your comment is submitted. Apr 12, Matt Chavez rated it really liked it. Yet, all too frequently, they rely on reproductions of faded drawings of uneven size and quality. This website uses cookies to improve your experience. My Cart. Go to my stream. Artur Kalil rated it liked it Aug 29, For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Kha Nguyen is currently reading it Feb 17, Every architecture student examines the Swiss master's work. Apr 12, Matt Chavez rated it really liked it. These remarkable new drawings-which combine the conceptual clarity of the section with the spatial qualities of the perspective-not only provide information about the buildings, they also help students experience specific works spatially as they learn to critically examine Le Corbusier's works. Error rating book. Trivia About Le Corbusier Redr Continue Shopping. Le Corbusier Redrawn presents the only collection of consistently rendered original drawings at scale of all twenty-six of Le Corbusier's residential works. Want to Read saving…. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. Welcome back. Rommel Lara rated it it was amazing Jul 12, Maison Planeix, Paris, France, ; These cookies do not store any personal information. -

Le Corbusier

LA CHAUX-DE-FONDS LE LOCLE LE CORBUSIER Le Corbusier Dans les Montagnes neuchâteloises In den Neuenburger Bergen In the mountains of Neuchâtel Né le 6 octobre 1887 à La Chaux-de-Fonds, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret prend en 1920 le pseudonyme de Le Corbusier, déformation du nom de l'arrière-grand-père maternel, Monsieur Lecorbésier. En 1902, il entre à l’Ecole d’art de la ville pour devenir graveur, mais l’un de ses professeurs, Charles L’Eplattenier l’oriente vers l’architecture, qu’il va découvrir à l’occasion de plusieurs séjours à Paris, Vienne, Berlin et lors de ses deux voyages en Italie (1907) et en Orient (1911). Il devient dès les années vingt l’un des architectes et urbanistes les plus influents de son siècle. Il est nommé citoyen d’honneur de sa ville natale en 1957 et meurt le 27 août 1965. Qui veut comprendre l’œuvre Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, de Le Corbusier, comme architecte, urbaniste, Le Corbusier peintre, sculpteur et homme de lettre égale - ment, doit suivre les premiers pas du maître à La Chaux-de-Fonds et au Locle et s’imprégner du caractère urbanistique et esthétique parti- culier des deux villes. Charles-Edouard Jeanneret wird am 6. Oktober 1887 in La Chaux-de-Fonds geboren. Sein Pseudonym Le Corbusier nimmt er 1920 in Anlehnung an Monsieur Lecorbésier, seinen Urgrossvater mütterlicherseits an. 1902 beginnt er eine Lehre zum Graveur an der Städtischen Kunstgewerbeschule. Unter dem Einfluss seines Lehrers Charles L’Eplattenier wendet er sich der Architektur zu, die er später bei Aufenthalten in Paris, Wien, Berlin und während seinen Orientreisen (1907 und 1911) entdeckt hatte. -

Communique De Presse

COMMUNIQUE DE PRESSE 20/07/16 World Heritage listing by UNESCO of « the architectural work of Le Corbusier, an outstanding contribution to the Modern Movement”: Gael Perdriau and Marc Petit welcome a major international award for the region. The Site Le Corbusier, located in Firminy, France – Europe’s largest collection of the works by the visionary architect - has finally been awarded World Heritage status. It is such a wonderful international recognition! Said Gael Perdriau, Maire of Saint-Etienne, President of Saint Etienne Métropole and Marc Petit, Maire of Firminy, Vice-President of Saint Etienne Métropole. As a result, the Culture Center of Firminy will become part of an international network of World Heritage Sites, joining the nearby city of Saint Etienne which is already listed as a ‘Creative City of Design’ by UNESCO. One of the features of this application is its unique international aspect. We would like to thank all the local residents, organizations and sponsors who have supported this campaign. The ‘Site Le Corbusier’ at Firminy - the second largest site after Chandigarh in India - is a major collection of architectural works. It is also a cultural, economic and touristic landmark, an invaluable asset for our region. The project strategy put in place by the City of Firminy and St Etienne Metropolitan Council will be enhanced by this award. It will lead to an increase in short and medium stay visits, an increase in hotel and restaurant bookings and furthermore, a boost to tourism in the wider region. » Open every day from 10 am to 12:30am and from 11:30 pm to 6 pm. -

The Architecture of Le Corbusier and Herzog and De Meuron

Traveling Studio Proposal - Spring 2018 Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning PARALLEL FACADES _ The Architecture of Le Corbusier and Herzog and De Meuron Instructor: Viola Ago Course Brief_ This travel course will take students through a trace of significant Architecture work by Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, and the duo Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron of Herzog and De Meuron (from now on HDM). This course will travel through three countries where most of the work in concentrated, Germany, Switzerland, and France. The curated list of buildings and sites has been constructed based on the utility of the façade in architecture. Both of these practices have been powerful influencers of architectural style. Le Corbusier was elementary to the emergence of Modernism and the removal of decorative arts in architecture. HDM were equally as fundamental in the evolution of Contemporary style and aesthetics in Architecture. Both contributors have used the Architectural Façade to express their aesthetic convictions and ideologies. This traveling studio will examine the Architectural Façade of Modern and Contemporary Architecture as it relates to three areas of investigation: art, technology, and agency. The visits to the sites, buildings, and collection based museums, will guide the students to collect information and knowledge on this critical part of history. The students will use the reading list as a guide to understand the current conditions of the Architectural Façade, and as a framework to inform the way in which to study the buildings that they will visit during this trip. Activity_ Traveling to sites, visiting buildings, visiting galleries, photography/sketching, taking notes, workshop participation.