1 Introduction Katharine Prentis Murphy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS by Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee

Field Notes - Spring 2016 Issue RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS By Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee We have been reviewing new books about the Olmsteds and the art of landscape architecture for so long that the book section of our website is beginning to resemble a bibliography. To make this resource more useful for researchers and interested readers, we’re beginning a series of articles about older publications that remain useful and enjoyable. We hope to focus on the landmarks of the Olmsted literature that appeared before the creation of our website as well as shorter writings that were not intended to be scholarly works or best sellers but that add to our understanding of Olmsted projects and themes. THE OLMSTEDS AND THE VANDERBILTS The Vanderbilts and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations 1879-1901. by John Foreman and Robbe Pierce Stimson, Introduction by Louis Auchincloss. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991, 341 pages. At his death, William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) was the richest man in America. In the last eight years of his life, he had more than doubled the fortune he had inherited from his father, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), who had created an empire from shipping and then done the same thing with the New York Central Railroad. William Henry left the bulk of his estate to his two eldest sons, but each of his two other sons and four daughters received five million dollars in cash and another five million in trust. This money supported a Vanderbilt building boom that remains unrivaled, including palaces along Fifth Avenue in New York, aristocratic complexes in the surrounding countryside, and palatial “cottages” at the fashionable country resorts. -

A Mechanism of American Museum-Building Philanthropy

A MECHANISM OF AMERICAN MUSEUM-BUILDING PHILANTHROPY, 1925-1970 Brittany L. Miller Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Departments of History and Philanthropic Studies, Indiana University August 2010 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________________ Elizabeth Brand Monroe, Ph.D., J.D., Chair ____________________________________ Dwight F. Burlingame, Ph.D. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the same way that the philanthropists discussed in my paper depended upon a community of experienced agents to help them create their museums, I would not have been able to produce this work without the assistance of many individuals and institutions. First, I would like to express my thanks to my thesis committee: Dr. Elizabeth Monroe (chair), Dr. Dwight Burlingame, and Dr. Philip Scarpino. After writing and editing for months, I no longer have the necessary words to describe my appreciation for their support and flexibility, which has been vital to the success of this project. To Historic Deerfield, Inc. of Deerfield, Massachusetts, and its Summer Fellowship Program in Early American History and Material Culture, under the direction of Joshua Lane. My Summer Fellowship during 2007 encapsulated many of my early encounters with the institutional histories and sources necessary to produce this thesis. I am grateful to the staff of Historic Deerfield and the thirty other museums included during the fellowship trips for their willingness to discuss their institutional histories and philanthropic challenges. -

Physical Accessibility Guide 2020

Physical Accessibility Guide 2020 Terrain Details for Paths, Walkways and Road Surfaces •Packed and loose gravel, slate, stone and brick. •Grade varies from easy to steep. Travel on the Grounds •Wheelchairs are available at the Museum Store. •Children's strollers and wagons are available at the Museum Store. •Accessible shuttle completes a circuit around the grounds approximately every 15 minutes. Service Accessibility •All services at the Museum Store and Café are fully accessible. •Additional accesible restrooms are located at Railroad Station and Stagecoach Inn. •The Ticonderoga reading room includes an Access and Explore notebook containing images and descriptions of areas of the boat that are not accessible. •Audio and/or video interpretive installations are located in exhibitions in Beach Gallery, the Ticondergoa, the Meeting House, Dorset House, and Variety Unit. •Handheld "i-loview" video magnifiers may be checked out at the Museum Store. The devices magnify up to 32x while also adjusting for brightness and contract, and are best for reading label text and signage. Generously donated by Ai Squared, a Vermont-based accessible technology company. Each exhibit building is listed below, including detailed information on accessibility. Unless otherwise noted, all steps are 8” high or less, and all doorways are at least 32” wide. This symbol indicates first floor accessibility Building Entrance Interior Exit Apothecary Shop Ramp on south side Same as entrance Beach Gallery Level entrance Level exit Beach Lodge Ramp on north side 2 interior -

Exhibit Building Accessibility

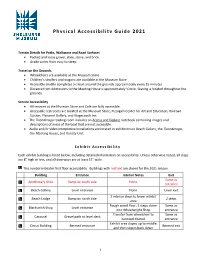

Physical Accessibility Guide 2021 Terrain Details for Paths, Walkways and Road Surfaces • Packed and loose gravel, slate, stone, and brick • Grade varies from easy to steep Travel on the Grounds • Wheelchairs are available at the Museum Store • Children’s strollers and wagons are available at the Museum Store • Accessible shuttle completes a circuit around the grounds approximately every 15 minutes • Distance from Admissions to the Meeting House is approximately ¼ mile. Seating is located throughout the grounds. Service Accessibility • All services at the Museum Store and Café are fully accessible. • Accessible restrooms are located at the Museum Store, Pizzagalli Center for Art and Education, Railroad Station, Pleissner Gallery, and Stagecoach Inn. • The Ticonderoga reading room includes an Access and Explore notebook containing images and descriptions of areas of the boat that are not accessible. • Audio and/or video interpretive installations are located in exhibitions in Beach Gallery, the Ticonderoga, the Meeting House, and Variety Unit. Exhibit Acces s i b i l i t y Each exhibit building is listed below, including detailed information on accessibility. Unless otherwise noted, all steps are 8” high or less, and all doorways are at least 32” wide. This symbol indicates first floor accessibility. Buildings with red text are closed for the 2021 season. Building Entrance Interior Notes Exit Same as Apothecary Shop Ramp on south side None entrance Beach Gallery Level entrance None Level exit 2 interior steps to lower exhibit Beach Lodge -

Carlquist Lloyd Hyde Thesis 2010.Pdf

1 Introduction As the Colonial Revival reached its zenith in the 1920s, collecting American antiques evolved from nineteenth-century relic hunting into an emerging field with its own scholarship, trade practices, and social circles. The term “Americana” came to refer to fine and decorative arts created or consumed in early America. A new type of Americana connoisseurs collected such objects to furnish idealized versions of America’s past in museums and private homes. One such Americana connoisseur was Maxim Karolik, a Russian-born tenor who donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston one of the most celebrated collections of American paintings, prints, and decorative arts. A report about the collection’s 1941 museum opening described how “connoisseurs looked approvingly” at the silver, “clucked with admiration” over the Gilbert Stuart portraits, and turned “green-eyed at the six-shell Newport desk-and-bookcase.”1 Karolik began collecting antiques in the 1920s, adding to those that had been inherited by Martha Codman Karolik, his “Boston Brahmin” wife. His appetite for Americana grew until he became one of the 1930s’ principal patrons, considered second only to Henry Francis du Pont. He scoured auction houses, galleries, showrooms, and small shops. Karolik loved the chase and consorting with dealers. He enjoyed haggling over prices despite his wife’s substantial fortune.2 1 “Art: Boston’s Golden Maxim,” Time (December 22, 1941). 2 Frieda Schmutzler (of Katrina Kipper’s Queen Anne Cottage), Oral History, May 26, 1978, Winterthur Archives. See also Carol Troyen, “The Incomparable Max: Maxim Karolik and the Taste for American Art,” American Art 7, n 3 (Summer 1993): 65-87. -

Massachusetts Massachusetts Office of Travel and Tourism, 10 Park Plaza, Suite 4510, Boston, MA 02116

dventure Guide to the Champlain & Hudson River Valleys Robert & Patricia Foulke HUNTER PUBLISHING, INC. 130 Campus Drive Edison, NJ 08818-7816 % 732-225-1900 / 800-255-0343 / fax 732-417-1744 E-mail [email protected] IN CANADA: Ulysses Travel Publications 4176 Saint-Denis, Montréal, Québec Canada H2W 2M5 % 514-843-9882 ext. 2232 / fax 514-843-9448 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: Windsor Books International The Boundary, Wheatley Road, Garsington Oxford, OX44 9EJ England % 01865-361122 / fax 01865-361133 ISBN 1-58843-345-5 © 2003 Patricia and Robert Foulke This and other Hunter travel guides are also available as e-books in a variety of digital formats through our online partners, including Amazon.com, netLibrary.com, BarnesandNoble.com, and eBooks.com. For complete information about the hundreds of other travel guides offered by Hunter Publishing, visit us at: www.hunterpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechani- cal, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Brief extracts to be included in reviews or articles are permitted. This guide focuses on recreational activities. As all such activities contain ele- ments of risk, the publisher, author, affiliated individuals and companies disclaim any responsibility for any injury, harm, or illness that may occur to anyone through, or by use of, the information in this book. Every effort was made to in- sure the accuracy of information in this book, but the publisher and author do not assume, and hereby disclaim, any liability for loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misleading information or potential travel problems caused by this guide, even if such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident or any other cause. -

MAJOR COLLECTION of 19TH-CENTURY AMERICAN ART OPENS May 9, 2004, at the NATIONAL GALLERY of ART

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: February 4, 2004 MAJOR COLLECTION OF 19TH-CENTURY AMERICAN ART OPENS May 9, 2004, AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Martin Johnson Heade Sunlight and Shadow: The Newbury Marshes, c. 1871-1875 oil on canv as, 30.5 x 67.3 cm (12 x 26 1/2) John Wilmerding Collection Washington, DC-- American Masters from Bingham to Eakins: The John Wilmerding Collection will showcase one of the most important private collections of 19th-century American art. The exhibition of 51 paintings by 26 American artists will be on view at the National Gallery of Art's East Building, May 9, 2004 through February 6, 2005. Works by such masters as George Caleb Bingham, Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Eakins, William Stanley Haseltine, Martin Johnson Heade, Fitz Hugh Lane, John Marin, John F. Peto, and William Trost Richards represent four decades of collecting in an area of particular scholarly interest to Wilmerding. "Over the course of his career John Wilmerding has become one of the most respected and widely known authorities on American art. His many books and articles have helped define the scholarly nature of the field as a whole and have also documented the works of key figures. John has organized many exhibitions on American art and through his teaching and lectures he has introduced literally thousands to the wonders and complexities of our national art," said Earl A. Powell III, director of the National Gallery of Art. -

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 SHELBURNE FARMS Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: SHELBURNE FARMS Other Name/Site Number: SOUTHERN ACRES FARM (southern portion only) 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1611 HARBOR ROAD Not for publication: N/A City/Town: SHELBURNE Vicinity: N/A State: VT County: CHITTENDEN Code: 007 Zip Code: 05482 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: ___ Site: ___ Public-Federal: Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 17 43 buildings _2_ sites 7 6 structures 1 3 objects 28 54 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 18 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 SHELBURNE FARMS Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

SHELBURNE MUSEUM Page 13

FAQ (5/27/21) ANSWERS TO FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS, 2021 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Page 2 ADMISSION Page 3 THE BRICK HOUSE Page 5 MEMBERSHIP Page 6 ACCESSIBILITY Page 8 VISITOR AMENITIES Page 9 CHANGES Page 11 BUILDING STAFFING AND ACCESSIBILITY Page 13 CAROUSEL Page 13 CHILDREN AT SHELBURNE MUSEUM Page 13 COLLECTIONS Page 14 CONSERVATION Page 15 GROUNDS Page 15 APPENDIX A – FAQs FOR PIZZAGALLI CENTER FOR ART AND EDUCATION Page 17 1 FAQ (5/27/21) SHELBURNE MUSEUM ANSWERS TO FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS, 2021 GENERAL INFORMATION Q: What is Shelburne Museum? A: The Museum, founded in 1947, is Vermont’s largest museum and one of the country’s finest, most diverse collections of art, design, and Americana. The product of a lifetime of collecting by Museum founder, Electra Havemeyer Webb, Shelburne’s collections range from folk art and architecture to fine art and transportation exhibits. Decorative arts, textile arts, and contemporary design fill the buildings. You may view paintings by Monet, Manet and Degas, hand carved circus figures, quilts, as well as a 220-foot steamboat, Ticonderoga, a National Historic Landmark. The Museum’s 45 acres of exquisite landscaping is home to 39 exhibit buildings. On August 18, 2013, the Museum opened the new Pizzagalli Center for Art and Education, a spectacular new exhibition and learning space with two 2,500 sf galleries, an auditorium with seating for 140 and a dedicated classroom. Q: How old is the Museum? A: The Museum was founded in 1947 and opened to the public in 1952. Q: Where is the Museum located? A: 6000 Shelburne Road, Shelburne, VT 05482 Q: What are the dates/hours the Museum is open? A: Museum grounds & gardens and select buildings will be open to the public starting June 2, 2021, with member early access June 1, 2021. -

Practical Environmental Control and Lighting at the Shelburne Museum

Preventive Conservation for Cultural Properties in Historic Buildings: Practical Environmental Control and Lighting at the Shelburne Museum Richard L. Kerschner Shelburne Museum Shaker Shed General Store Dutton House Class 1: Open Structures Covered Bridge Locomotive 220 Class 2: Sheathed Post and Beam Structures Horseshoe Barn Class 3: Framed Wood or Uninsulated Masonry Structures Prentis House Class 4: Tight Wooden or Heavy Masonry Structures Dorset House Class 5: New-built Insulated Structures, Vapor Barriers Pleissner Gallery Class 6: Double-wall Construction, Storage Vaults Museum Library Roof Gutters Storm Drains Dust Control Insulation Conservation Ventilation (humidistatically controlled) Conservation Heating (humidistatically controlled) Prentis House Modified Use of Conventional HVAC Systems Hat and Fragrance Unit Conventional HVAC System with Low-Level Humidification Stagecoach Inn OT>320F = 45%RH 320F>OT>200F = 40%RH OT<100F = 35%RH Vaisala RH Sensor Practical Environmental Control for Newer Buildings Collections Preservation Building Conservation Heating with DX Cooling Decorative Arts Storage Decorative Arts Storage T and RH 2003 NEW STORAGE-2003-04.pdf Decorative Arts Storage T and RH 2005 Circus Building Carousel Goat with Mold on Leather Fluorescent – Lux X 100 Xenon – Lux X 10 Xenon Miniature Track Lights RGB LED Lights 50 Lux 280 Lux Bronze Tinted Plexiglas on Window No Filter on Window 95% of Natural Light Blocked Bright LEDs - Inconsistent Color LIA Alternating Nichia E2 and F2 LEDs LIA RIA Dolls Lit by MR16 Halogen -

2018-Visitors-Guide-Map.Pdf

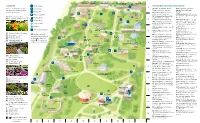

Print Shop Weaving Shaker Shed Jail Hat and Fragrance Toy Variety Unit s Shop Textile Gallery s Shop GARDENS Food Service SHELBURNE MUSEUM BUILDINGS 1 With 22 beautiful gardens, visitors Information G9 Admissions and Museum Store H8 Pizzagalli Center for Art and will find an array of exquisite plants Ticketing, information, and more. Education (2013) See Exhibition blooming in any season. Restrooms E4 Apothecary Shop (1959) Patent Highlights. Stone Cottage Water Fountains medicines, medical equipment. C5 Pleissner Gallery (1986) Landscape and sporting art. Upstream with Ogden A7 Railroad Station Gardens D5 The Artisans Shop/Diamond Barn Horseshoe Horseshoe Smokehouse Pleissner. B10 Circus Building Daylily Garden t Shuttle Route Barn (South Shaftsbury, VT, ca. 1805) Barn Annex 2 A retail gallery of New England crafts. F5 Prentis House (Hadley, MA, 1773) Shuttle Stops Schoolhouse Colonial Revival installation of 17th– Stagecoach C8 Beach Gallery (1960) Lock, Stock Tour Location Inn s and Barrel: The Terry Tyler Collection 18th century furniture and decorative of Vermont Firearms. arts. Open for guided tours only. See Tours and Talks. Garden Meeting C8 Beach Lodge (1960) Adirondack life House E1 Print Shop (1955) Presses from Vermont House and hunting. Bench Space locations the 1820s to 1950s. Gallery s Covered Bridge 3 C3 Blacksmith Shop (Shelburne, VT, 1800). B8 Rail Car Grand Isle (1890) C5 Gardens of Pleissner Courtyard sStrollers and child B8 Railroad Freight Shed (1963) Steam E3 Meeting House Garden Dutton B9 Carousel (North Tonawanda, NY, backpacks are prohibited Blacksmith House s Dorset ca. 1920) Travelling carnival model by engine replica. E4 Apothecary Garden s in buildings identified Shop House Herschell-Spillman Company. -

Cultivating the Crafts: Aileen Osborn Webb and the Instituting of American Craft, 1934-1964

CULTIVATING THE CRAFTS: AILEEN OSBORN WEBB AND THE INSTITUTING OF AMERICAN CRAFT, 1934-1964 Stephen Brandon Hintze Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2008 ©2009 Stephen Brandon Hintze All Rights Reserved Table of Contents List of Illustrations………………………………………………………..…...ii Preface………………………………………………………………………..ix Introduction……………………………………………………….…………...1 Chapter 1: The 1910s-1920s: A Philanthropic Beginning………..….………..4 Chapter 2: The 1930s: Marketing the Crafts………………………….…..….15 Chapter 3: The 1940s: Advocacy and Outreach..……………………………20 Chapter 4: The 1950s: Exhibitions and Conferences………..…………….…32 Chapter 5: The 1960s: Diplomacy through Craft…….……………….……..41 Conclusion……………………………………………………………….…..53 Appendices…………………………………….……………………………..55 Appendix 1: Family Tree of Aileen Osborn Webb………………………..…56 Appendix 2: Amended By-Laws— World Craft Council…...…………....…57 Appendix 3: A Suggested Plan for Rural Development………………..........65 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………75 Illustrations……………………………………………………………….….83 i List of Illustrations Fig.1 Aileen Osborn Webb in her apartment potter’s studio, New York, New York, 1966. From Rita Reif, “A Mover in the Field of Crafts,” New York Times, January 8, 1966. Fig. 2 Osborn Family Photograph, Garrison, New York, c.1900. From Osborn Family Archives, Garrison, NY. Fig. 3 Aileen Osborn Webb as a young debutante, New York, New York, c.1910. From Aileen Osborn Webb Papers, Shelburne Farms Archives, Shelburne, VT. Fig. 4 Aileen Osborn as a young, engaged woman (top); Aileen Osborn and Vanderbilt Webb during their engagement, probably Garrison, New York, c.1912 (bottom). From Aileen Osborn Webb Papers, Shelburne Farms Archives, Shelburne, VT.