Shelburne Museum"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Color As Expression

MUSEUM LEARNING: PLANS & RESOURCES Using Color as Expression We are going to explore colors, how we see them, and the ways we can mix them to create amazing art. By exploring an important painting at Shelburne Museum–The Grand Canal, Venice (Blue Venice) painted by Edouard Manet in 1875, we will look closely at how the artist used color to create his masterpiece. Goals We will learn some art vocabulary to identify color schemes, explore Manet’s techniques and create our own version of Manet’s The Grand Canal, Venice painting. Edouard Manet, The Grand Canal, Venice (detail), 1875. Oil on canvas, Background Information 23 1/8 x 28 1/8 in. Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc. 1972 69.15. In 1875, Manet painted this view on the Grand Canal, which H. O. Havemeyer purchased for his wife Louisine 20 years later. She was particularly fond of More Resources the picture and changed its name to Blue Venice. Mrs. Havemeyer wrote that her friend Mary Cassatt n Edouard Manet (1832-83), The Met, “congratulated us when we bought this picture, https://bit.ly/`met-SM saying she considered it one of Manet’s most brilliant n What’s the Difference between Manet and Monet, works; it was so full of light and atmosphere and The Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty, expressed the very soul and spirit of Venice.” Her https://bit.ly/Getty2-SM daughter Electra Havemeyer Webb inherited Blue n Impressionism: Art & Modernity, The Met, Venice, which hangs in the living room of her New https://bit.ly/met1-SM York City apartment, reinstalled in Shelburne Museum’s Memorial Building. -

Shelburne, Vermont - a Site on a Revolutionary War Road Trip

Shelburne, Vermont - A Site on a Revolutionary War Road Trip http://revolutionaryday.com/usroute7/shelburne/default.htm Books US4 NY5 US7 US9 US9W US20 US60 US202 US221 Canal Shelburne Museum's Sawyer's Cabin from East Charlotte, Vermont Shelburne Museum — The museum is a collection of architectures, artifacts and art from America’s past. Many items in the collection date back to the Revolutionary War period. One of the oldest homes is the Preston House. It was built in 1773 in Hadley, Massachusetts and moved to its present site in 1955. Another old home is the Dutton House. It was built in Cavendish, Vermont in 1782. Both houses are of the old “saltbox” style that was commonly found in colonial New England. The museum's Stagecoach Inn was once on the old colonial route paralleling today’s US Route 7 in Charlotte (pronounced Sha-Lot by Vermonters) in 1783. Charlotte is just south of Shelburne near Lake Champlain. Although the Revolutionary War did not officially end until November of 1783, hostilities began to subside after America’s victory at Yorktown in October 1781. With the construction of inns like the Stagecoach Inn, life in northern Vermont was returning back to normal. One of the museum's most popular exhibits is the steamship Ticonderoga, America's last vertical beam, side-wheel, passenger steamboat from 1906. The ship is grounded at the museum and in pristine condition. 1 of 3 6/16/17, 4:55 PM Shelburne, Vermont - A Site on a Revolutionary War Road Trip http://revolutionaryday.com/usroute7/shelburne/default.htm Village Center — Just north of the museum is the village center. -

Physical Accessibility Guide 2020

Physical Accessibility Guide 2020 Terrain Details for Paths, Walkways and Road Surfaces •Packed and loose gravel, slate, stone and brick. •Grade varies from easy to steep. Travel on the Grounds •Wheelchairs are available at the Museum Store. •Children's strollers and wagons are available at the Museum Store. •Accessible shuttle completes a circuit around the grounds approximately every 15 minutes. Service Accessibility •All services at the Museum Store and Café are fully accessible. •Additional accesible restrooms are located at Railroad Station and Stagecoach Inn. •The Ticonderoga reading room includes an Access and Explore notebook containing images and descriptions of areas of the boat that are not accessible. •Audio and/or video interpretive installations are located in exhibitions in Beach Gallery, the Ticondergoa, the Meeting House, Dorset House, and Variety Unit. •Handheld "i-loview" video magnifiers may be checked out at the Museum Store. The devices magnify up to 32x while also adjusting for brightness and contract, and are best for reading label text and signage. Generously donated by Ai Squared, a Vermont-based accessible technology company. Each exhibit building is listed below, including detailed information on accessibility. Unless otherwise noted, all steps are 8” high or less, and all doorways are at least 32” wide. This symbol indicates first floor accessibility Building Entrance Interior Exit Apothecary Shop Ramp on south side Same as entrance Beach Gallery Level entrance Level exit Beach Lodge Ramp on north side 2 interior -

NELL Beacon January 2011 FINAL

New England Lighthouse Lovers A Chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation NELLNELL BeaconBeacon January 2011 NELL’S 2010 YEAR IN REVIEW By Tom Kenworthy, NELL President he weather for the weekend of January 14 Light Foundation (NLLLF). In T and 15, 2010 was sunny with blue skies: his request, Anthony stated perfect for NELL’s annual Lighthouses, Hot NLLLF needed help in Chocolate & You weekend. The Hilton Hotel, scraping, spackling, and Mystic CT was our host hotel. general cleaning. He also stated that the only reason We first visited Morgan Point the work party would be Lighthouse for our 2004 cancelled would be due to LHHC&Y. Having received so inclement weather and/or high many requests to visit/revisit seas. Thankfully, the weather, Morgan Point Lighthouse, it wind, and waves were calm and Anthony made good sense to use that reported that much was accomplished and he is as our starting point for our looking forward to another Project H.O.P.E. at 2010 LHHC&Y. the Ledge Light sometime in the coming year. Leaving Morgan Point, we made the short drive Receiving many requests from our members to to USS Nautilus and the Submarine Force travel to “foreign lands” (outside of New Museum. Here, members decided which to England), Ron and Mike put together a trip to visit first, with it being about a 50-50 split. I the St. Lawrence Seaway. On the weekend of went to the museum first and then toured the May 14-16, we went to lands not traveled to by Nautilus. -

Exhibit Building Accessibility

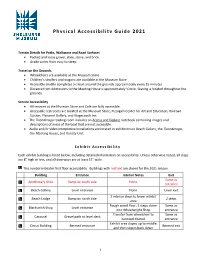

Physical Accessibility Guide 2021 Terrain Details for Paths, Walkways and Road Surfaces • Packed and loose gravel, slate, stone, and brick • Grade varies from easy to steep Travel on the Grounds • Wheelchairs are available at the Museum Store • Children’s strollers and wagons are available at the Museum Store • Accessible shuttle completes a circuit around the grounds approximately every 15 minutes • Distance from Admissions to the Meeting House is approximately ¼ mile. Seating is located throughout the grounds. Service Accessibility • All services at the Museum Store and Café are fully accessible. • Accessible restrooms are located at the Museum Store, Pizzagalli Center for Art and Education, Railroad Station, Pleissner Gallery, and Stagecoach Inn. • The Ticonderoga reading room includes an Access and Explore notebook containing images and descriptions of areas of the boat that are not accessible. • Audio and/or video interpretive installations are located in exhibitions in Beach Gallery, the Ticonderoga, the Meeting House, and Variety Unit. Exhibit Acces s i b i l i t y Each exhibit building is listed below, including detailed information on accessibility. Unless otherwise noted, all steps are 8” high or less, and all doorways are at least 32” wide. This symbol indicates first floor accessibility. Buildings with red text are closed for the 2021 season. Building Entrance Interior Notes Exit Same as Apothecary Shop Ramp on south side None entrance Beach Gallery Level entrance None Level exit 2 interior steps to lower exhibit Beach Lodge -

ED350244.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 350 244 SO 022 631 AUTHOR True, Marshall, Ed.; And Others TITLE Vermont's Heritage: A Working Conferencefor Teachers. Plans, Proposals, and Needs. Proceedingsof a Conference (Burlington, Vermont, July 8-10, 1983). INSTITUTION Vermont Univ., Burlington. Center for Researchon Vermont. SPONS AGENCY Vermont Council on the Humanities and PublicIssues, Hyde Park. PUB DATE 83 NOT:, 130p.; For a related document,see SO 022 632. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Education; *Curriculum Development; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; Folk Culture; Heritage Education; *Instructional Materials; Local History;*Material Development; Social Studies; *State History;Teacher Developed Materials; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Vermont ABSTRACT This document presents materials designedto help teachers in Vermont to teachmore effectively about that state and its heritage. The materials stem froma conference at which scholars spoke to Vermont teachers about theirwork and about how it might be taught. Papers presented at the conferenceare included, as well as sample lessons and units developed byteachers who attended the conference. Examples of papers includedare: "The Varieties of Vermont's Heritage: Resources forVermont Schools" (H. Nicholas Muller, III); "Vermont Folk Art" (MildredAmes and others); and "Resource Guide to Vermont StudiesMaterials" (Mary Gover and others). Three appendices alsoare included: (1) Vermont Studies Survey: A Report -

American Quilts

CATALOGUE AMERICAN QUILTS 1819 -- 1948 From the Museum Collection Compiled by Mildred Davison The Art Institute of Chicago, Department of Decorative Arts Exhibition April 20, 1959 - October 19, 1959 AMERICAN QUILTS 1819 - 1948, FROM THE MUSEUM COLLECTION The Art Institute of Chicago, April Z0 1 1959 --October 19, 1959 Although patchwork has been known and practised since ancient times, nowhere has it played such a distinctive and characteristic part as in the bed covers of early America where it added the finishing touches to eighteenth and nineteenth century bed chambers. The term "patchwork" is used indiscriminately to include the pieced and the appliqued quilts. Pieced quilts are generally geometric in pattern being a combination of small patches sewn together with narrow seams. The simplest form of pieced pattern is the eight-pointed star formed of diamond shaped patches. This was known as the Star of Le Moyne, named in honor of Jean Baptiste Le Moyne who founded New Orleans in 1718, and from it was developed numerous others including all of the lily and tulip designs. In applique quilts, pieces were cut to form the pattern and appliqued to a back - ground material with fine hemming or embroidery stitches, a method which gave a wider scope for patterns. By 1850, applique quilts reached such a degree of elaboration that many years were spent in their making and they were often intend ed for use as counterpanes. The most common fabrics for quilts were plain and figured calicoes and chintzes with white muslin..., The source of these materials in early times and pioneer communities was the scrap bag. -

Geospatial Mapping of the Landward Section of Mount Independence Project Grant #GA-2287-16-020

Geospatial Mapping of the Landward Section of Mount Independence Project Grant #GA-2287-16-020 A Cooperative Project between the American Battlefield Protection Program and the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation Jess Robinson, PhD 2018 Acknowledgements The author and the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation (VDHP) wish to thank the National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Program and specifically Kristen McMasters, for her assistance through the grant cycle. We also wish to extend our thanks to the Mount Independence Coalition for their support and encouragement. Additional thanks are gratefully extended to: Mike Broulliette, John Crock, PhD, Kate Kenny, Otis Monroe, Brett Ostrum, and Melissa Prindeville for their help with this project. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... ii Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. v Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Mount Independence Physical Geography ..................................................................................... 1 Historical Background ................................................................................................................... -

A Car That Looks Dirty 10 Months a Year Adirondack Furniture Alchemist

A car that looks dirty 10 months a year Adirondack Furniture Alchemist Beer Antique wooden sap bucket Apple picker Apples Archer Mayor novels Arlington Covered Bridge Arrow head Attached barns Auger (ice fishing) Bag Balm Bag of King Arthur flour Barn boots Barre Granite Barre Police Blotter Basketball hoop at the Barre Auditorium Beer Bottle Bellows Falls Tunnel Ben and Jerry's Bennington Battle Monument Bennington Church Bennington pottery Bernie Sanders bumper sticker Bicycles: Touring, Mountain, and Cruiser Billings Museum Black Fly Blue Heron Brattleboro Strolling of the Heifers Bread and Puppet Theater Bristol Outhouse Race Butter churn Cabot cheddar Calcified schist from the Ct valley Camel’s Hump Camps on the lake Canoe Carved Abenaki face on the granite riverbed at Bellows Falls Cast iron anything Catamount Trail blue diamond blaze Chainsaw. Champ Cheap Plastic Sled Cider press Clothespin Cochran family Comb Honey Connecticut River Coolidge Homestead Coop membership card Country store Covered bridges Cow pie CRAFT BEER! Creemee Cross country skis Crown Point Road Cupolas Danby Quarries Darn tough socks dead skunks in the road deep snow Deer antlers Deer Rifle Dirt Road Doll with Movable Joints Dousing rod Doyle Poll Drunken UVM student Ear of Indian corn Eat More Kale bumper sticker or t-shirt Estey Organ Ethan Allen Ethan Allen furniture Ethan Allen Homestead Eureka Schoolhouse Fall Foliage Farm stands Farmers market Fiddleheads Fieldstone walls from clearing farmland Fish Tails sculpture along I-89 Fishing Floating Bridge Foliage Train Four leaf lover Frost heave Furniture and other wood products Gilfeather Turnip Gillingham's store in Woodstock GMC lean-to shelter Goddess of Agriculture atop State House Gondolas Granite Granite monuments in Barre Green bags of Green Up Day Green Mountains Green Mountains Green Mt. -

AVERAGIUM Newsletter of Harvey Ashby Limited, Average Adjusters & Claims Consultants Summer 2000

AVERAGIUM Newsletter of Harvey Ashby Limited, Average Adjusters & Claims Consultants Summer 2000 Is this a warranty I see before me? We have always stressed to our clients the importance of complying with warranties contained in their policies. These range in character from the ‘warranted classed and class maintained’ provision contained in the vast majority of marine hull policies, to survey warranties which require the approval of specified surveyors to certain operations conducted under offshore construction projects. The reason for this is not only the effect that a breach of warranty might have on the recoverability of a loss sustained as a result of the breach; but also the additional draconian penalty which can be applied by insurers. “JUPITER” - Bay City, September 1990 (NOAA) The Marine Insurance Act [1906] provides that a warranty is a condition which must be exactly complied with and if it is not, the breach of a warranty under the policy would be a bar to a the insurer is discharged from liability as from the date of the claim whether or not it was material to any such claim. breach. It is, of course, always open to an insurer to waive a Nevertheless, the Judge decided that the warranty was not a breach, or the policy may provide for some alternative penalty; warranty but a ‘suspensive condition’ the effect of which was nevertheless the fact, and the risk, remains that an insurer may merely to suspend cover from the time that the inspection was avoid all liability under the policy from the date of the breach. -

BMWMOA Rally 2006

So Many Things – So Little Time How to use this interactive document: 1. Do not print this document, not at first. The links will 6. Exploring the document lead you hundreds of inter- could easily take hours. esting and fun places. That’s fine especially if you live when the Northeast. But 2. Connect to the internet and planning and scheming is open this document – Ver- half the fun. Think of the mont Attractions. time and gasoline you will save by exploring Vermont 3. Before you go much further by using the internet. please put the following number in your cell phone: 7. BMW MOA will have an 1-802-847-2434. That is the unbeatable program of Emergency Department speakers, and special events. and Level I Trauma Center Plan your Vermont rides in BURLINGTON. You and exploration now. There might save a life while at the is much more to see and do rally. than time will allow so pre- pare now for a memorable 4. Start by exploring page 4 rally. which is a summary of the better known sites in Ver- 8. Vermont will have great mont. weather to enjoy and unbeat- able roads to ride. If you are 5. If you are connected to the looking for the local club web you will be connected to come visit us here. the website tied to that link. Come Early – Stay Late. Page 1 of 48 Last update: 1/30/2006 So Many Things – So Little Time 2006 will be one of the best rallies When first starting this project I hoped to ever! Vermont is an outstanding riding locale. -

Impressionist Still Life 2001

Impressionist Still Life 2001- 2002 Finding Aid The Phillips Collection Library and Archives 1600 21st Street NW Washington D.C. 20009 www.phillipscollection.org CURATORIAL RECORDS IN THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION ARCHIVES INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION Collection Title: Impressionist Still Life; exhibition records Author/Creator: The Phillips Collection Curatorial Department. Eliza E. Rathbone, Chief Curator Size: 8 linear feet; 19 document boxes Bulk Dates: 1950-2001 Inclusive Dates: 1888-2002 (portions are photocopies) Repository: The Phillips Collection Archives INFORMATION FOR USERS OF THE COLLECTION Restrictions: The collection contains restricted materials. Please contact Karen Schneider, Librarian, with any questions regarding access. Handling Requirements: Preferred Citation: The Phillips Collection Archives, Washington, D.C. Publication and Reproduction Rights: See Karen Schneider, Librarian, for further information and to obtain required forms. ABSTRACT Impressionist Still Life (2001 - 2002) exhibition records contain materials created and collected by the Curatorial Department, The Phillips Collection, during the course of organizing the exhibition. Included are research, catalogue, and exhibition planning files. HISTORICAL NOTE In May 1992, the Trustees of The Phillips Collection named noted curator and art historian Charles S. Moffett to the directorship of the museum. Moffett, a specialist in the field of painting of late-nineteenth-century France, was directly involved with the presentation of a series of exhibitions during his tenure as director (1992-98). Impressionist Still Life (2001-2002) became the third in an extraordinary series of Impressionist exhibitions organized by Moffett at The Phillips Collection, originating with Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir‟s Luncheon of the Boating Party in 1996, followed by the nationally touring Impressionists in Winter: Effets de Neige, on view at the Phillips in 1998.