Making a Difference: the Strategic Plan for Duke University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making a Difference: the Strategic Plan for Duke University

Making a Difference: The Strategic Plan for Duke University September 14, 2006 The Mission of Duke University James B. Duke’s founding Indenture of Duke University directed the members of the University to “provide real leadership in the educational world” by choosing individuals of “outstanding character, ability and vision" to serve as its officers, trustees and faculty; by carefully selecting students of “character, determination and application;” and by pursuing those areas of teaching and scholarship that would “most help to develop our resources, increase our wisdom, and promote human happiness." To these ends, the mission of Duke University is to provide a superior liberal education to undergraduate students, attending not only to their intellectual growth but also to their development as adults committed to high ethical standards and full participation as leaders in their communities; to prepare future members of the learned professions for lives of skilled and ethical service by providing excellent graduate and professional education; to advance the frontiers of knowledge and contribute boldly to the international community of scholarship; to promote an intellectual environment built on a commitment to free and open inquiry; to help those who suffer, cure disease, and promote health, through sophisticated medical research and thoughtful patient care; to provide wide ranging educational opportunities, on and beyond our campuses, for traditional students, active professionals and life-long learners using the power of information technologies; and to promote a deep appreciation for the range of human difference and potential, a sense of the obligations and rewards of citizenship, and a commitment to learning, freedom and truth. -

View Landscape Guidelines

UNIVERSITY Duke LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AND DESIGN GUIDELINES MAY 2014 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR THE DUKE CAMPUS LANDSCAPE 5 DESIGN CHARACTER 26 MATERIAL COLOR RANGE 27 LANDSCAPE TYPOLOGIES HISTORIC LANDSCAPES 9 West Quad 10 East Quad 11 NATURALISTIC LANDSCAPES 13 Reforestation and Managed Woodlands 14 Ponds, Streams, Wetlands and Raingardens 15 Parkland 16 PUBLIC LANDSCAPES 17 Plazas 18 Gardens 19 Courtyards and Terraces 20 Pedestrianways 21 CAMPUS FABRIC 23 Streetscapes 24 Interstitial Spaces 25 DESIGN ELEMENTS 27 Paving Bluestone 28 Concrete Pavers 30 Exposed Aggregate Concrete 31 Brick Pavers 32 Miscellaneous 33 Sitewalls Duke Stone 34 Duke Blend Brick 38 Other Masonry 39 Concrete 40 Miscellaneous 41 Steps and Railings Steps 42 Railings 43 Accessibility 45 Fences and Gates 46 Site Furniture Seating 47 Bike Racks 48 Bollards 48 Exterior Lighting 49 Waste and Recycling Receptacles 49 3 Duke’s campus is relatively large and spread out compared to many other universities. The main part of campus - aside from the Duke Forest and other properties - is nearly 2000 acres, with approximately 500 acres of that being actively maintained. The large amount of tree coverage, road network, topography, and natural drainage system, along with extensive designed landscapes, athletic fi elds and gardens, makes the campus an incredibly rich and complex place. These guidelines are intended to be a resource for creating and maintaining a campus landscape with a certain level of consistency that exists across various precincts with specifi c contextual requirements. These guidelines will help to set the character for the different landscape types while also providing detailed recommendations and precedents for what has and has not worked on campus previously. -

VITA-Full April 2018

April 2018 CATHY N. DAVIDSON Distinguished Professor, Ph.D. Program in English Founder and Director, The Futures Initiative The Graduate Center, CUNY 365 Fifth Avenue, Room 3314 New York, NY 10016-4309 212-817-7247 [email protected] Ruth F. DeVarney Professor Emerita Duke University Co-Founder and Co-Director, HASTAC (hastac.org) http://www.cathydavidson.com EDUCATION Postdoctoral study, The University of Chicago, 1975-1976; in linguistics and literary theory Ph.D., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1974; in English M.A., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1973; in English B.A., Elmhurst College, 1970; in philosophy (logic) and English EMPLOYMENT The Graduate Center, CUNY July 2014- Distinguished Professor and Director, Futures Initiative Duke University July 2014-2017 Ruth F. DeVarney Professor Emerita of Interdisciplinary Studies and Distinguished Visiting Professor 2012-2014 Co-Director, Ph.D. Lab in Digital Knowledge 2006-2014 John Hope Humanities Institute Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies 1998-2006 Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies 1999-2003 Co-Founder and Co-Director, John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute 1996-2014 Distinguished Professor Ruth F. DeVarney Professor of English 1989-present Professor of English 1989-1999 Editor, American Literature Autonomous University 1991 Visiting Professor (Barcelona, Spain) Princeton University 1988-1989 Visiting Professor of English Michigan State University 1976-1989 Assistant, Associate (1981), and Full (1986) Professor of English Kobe Jogakuin Daigaku 1987-1988 Visiting Professor of English (Kobe Women’s College, Japan) 1980-1981 Exchange Professor of English Bedford College 1982 Michigan State University/London (University of London) Exchange Program St. Bonaventure University 1974-1975 Visiting Instructor AWARDS, HONORS, RECOGNITION 2018 Consultant, John D. -

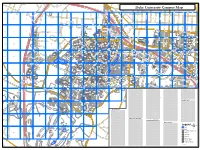

East Campus West Campus

16 1 5 - 5 0 1 Clocktower Duke Gardens East Campus Perkins Library Duke Chapel Wallace Wade Stadium Gargoyle Medical Center Sociology/Psychology Duke Forest Kilgo Quad Cameron Indoor Stadium Chapel Drive West Union Fitzpatrick Center Wilson Rec Duke Gardens Crowell Quad Levine Science Research West Union Quad East Campus Union The Ark Wilson Residence Hall East Campus Entrance Williams Field Baldwin Auditorium Lilly Library E R W I N R O A D M A R K H A M A V E N U E AST AMPUS uke University traces its roots to 1838, when it was established as Union Institute in Randolph County, North Carolina. In E C Branson 17 As you begin your East Campus tour near the North Theater 1892 the school—renamed Trinity College—relocated to Durham on what is now East Campus. In 1924, Trinity College, a Phyto Baldwin main bus stop, you’ll be in the midst of many of the Auditorium long-time beneficiary of Duke family generosity, became the nucleus of Duke University. With a $21 million gift from James tron VA Ho Greenhouses 5 East Campus residence halls, home to all first-year Biddle MORREENE RD Art D To Duke Forest/Primate Ctr sp WE Music Bldg. Bishop's House CIRCUIT DRIVE it Building 21 B. Duke, West Campus was created and East Campus was rebuilt. Today, Duke consists of a breathtaking 9,350-acre campus that LASALLE ST al students. Although students are assigned randomly WXDU Radio (Continuing Ed) . DRIVE s. French Science Center Eye Cente es r Re includes two undergraduate schools, seven graduate and professional schools, a world-renowned medical center, a 7,900-acre forest, Levine Sc to housing, they can state preferences T 22 (under construction) ienc To NC a15-501 n d I - 8 S e Research Hall Hall and a beautiful 55-acre garden. -

Duke University Campus Map S D U T G

E V A A I G G O R L O F E S G EN T GLEWOOD AVE E T V H S I A LL LAWNDALE AVE L S D B L L I T O E I H S R F E O T E S N T Duke University Campus Map S D U T G S O O G Y S R D R D R H E E N W E L E S S R E T E T O L D A R S L R K A A A S M R Y L N C O D E W C N N B O T H N 1 A A D 0 L R 5 - 7971 L 5 C L 1 I R O H D R AM N T W KNOX ST ERIC A B C U D E E N R O V A V S K A S L A T W L A T E S 7956 B A T D R E A S N D Z E N KANGARO M T I N O DR I L H S A A A G T T L T A O I E V R S K I S R L CREST ST T E D V H S A A E A D S T O C A1 B1 C1 D1 E1 F1 G1 H1 I1 J1 K K1 L1 H M1 N1 O1 P1 N C A I I H M N O O R R R B E S H E T N I R S E MCQU EEN L R DR T E N S D E Y O D S M R S T A 7582 U D T S L L N GR WE D EEN ST E N G N U E A S Y U 7593 D F T R M O R T D D S ID N A E L R E B E B L 8239 R E2 I A O2 E C C W T A T S R DOWNING ST L WARNER ST L E PRATT ST 7636 D 7637 HILLSBOROUGH RD E R I 7631 7634 S AF 7633 7635 EW AY ST A2 B2 C2 D2 F2 G2 H2 I2 ELDER ST J2 K2 L2 M2 N2 P2 7650 CAMPUS W W M ALK AVE T ARKHAM AVE S 7654 7651 F 8120 L 7656 B E T 7653 T 7229 A N S I R LDW 7251 8140 8050 E D LOOP ELBA ST N R 7232 T LOUIS O E F S 7219 C T I R R T S 7218 7523 E 7527 7228 H H 7209 T URBAN RD W T G B 7220 IN U R ERW 7553 R Y OD N R 7276 M I AVE D M D E A E T #10 ALY R T IN E S N S T 8304 H3 H 7217 P3 E T F I 7528 T R F 7231 7510 T N 7515 I 7221 S L 7555 N A 7561 S 7536 8116 7275 NEWELL ST A LL 7557 E 7514 PUS DACIAN S 7531 7272 7226 CAM T 7216 ST T 7222 EA N DR AVE E C DR PE NIO M G RRY U O N R ST EN KI 7548 7511 G AR D S P ND 7534 Y A3 B3 C3 D3 E3 F3 G3 SA I3 -

Electronic Techtonics: Thinking at the Interface

ELECTRONIC TECHTONICS: THINKING AT THE INTERFACE Proceedings of the First International HASTAC Conference Duke University, Durham, North Carolina April 19-21, 2007 EDITORS: Erin Ennis Zoë Marie Jones Paolo Mangiafico Mark Olson Jennifer Rhee Mitali Routh Jonathan E. Tarr Brett Walters This conference was organized by the “Interface” Seminar of the John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University as its contribution to HASTAC’s In|Formation Year. Copyright © 2008 HASTAC HASTAC uses Creative Commons licenses for all of its endeavors. Electronic Techtonics: Thinking at the Interface sessions and presentations are available in streaming format on the HASTAC website, http://www.hastac.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Published by Lulu Press http://stores.lulu.com/hastac Cover design by Jason Doty. ISBN 978-1-4357-1362-8 CONTENTS Preface iv Acknowledgments v About HASTAC viii The 1st International HASTAC Conference Program x Opening Remarks 1 Cathy N. Davidson Panel 1: Funding the Digital Future* 5 Brett Bobley Karl Brown Jerry Heneghan Gary Kebbel Kevin M. Guthrie Steven C. Wheatley Constance M. Yowell Panel 2: Interface Genealogies Caitlin Fisher 7 “Interface Epistemology: Hypermedia Work in the Academy” Lisa Gitelman** “Xerographers of the Mind: The -

Orientation Workbook for First-Year Students at Duke University, 2018

DUKE | 2018-19 This belongs to: Contact: 15-50 1 E RWIN ROAD E R W I N R O A D M A R K H A M A V E N U E Branson JB Duke Building Hotel 0 1 & Phytotron Baldwin Environment Hall VA Hospital Biddle Auditorium R. David Thomas Duke MORREENE RD Greenhouses Music 8 5 Art To Duke Forest/Lemur Ctr Executive Softball WXDU Bishop's House Conference CIRCUIT DRIVE CIRCUIT DR Radio Building Bldg. Parking Garage Stadium (Continuing Ed) Center Eye Center NC 15-5 4 Levine Science Research Center French Family T o and I- Hall Fuqua Science Center Hall Bassett Res. Bassett School RESEARCH DRIVE Brookwood Bivins Bldg. Res. Pegram Gross Inn of Law Hall North Bldg FULTON STREET Business School Biological courtyard Physics Benjamin Duke Sciences and Math Engineering Library and Teer Bryan Seeley Statue Academic Advising 1 Engineering Administration Research Bldg Center Hall Hudson Hall Mudd Hall (Searle Ctr) Duke Hospital Brown Res. Brown Alspaugh Res. Alspaugh SCIENCE DRIVE SCIENCE DRIVE NINTH STREET Pratt North Williams Field Medical Athletic Field East Parking Garage Engineering at Jack Katz Memorial Sanford FCIEMAS Center Lilly Campus 18 East Stadium Gym/ Campus Marketplace Dining/ School 20 Parking Brodie Rec Library Store Reynolds Theater, 11 Union 17 Trinity Cafe 2 19 Garage Center Griffith Theater BROAD STREET E University Fitzpatrick Center Tennis Courts V Mary Trent Semans I Bryan Jack Coombs for Interdisciplinary Inn Washington R Student Bookstore Medical Education Hall D Center Duke Inn Stadium Wellness Engineering, Medicine, Bell Tower s. D 5 Building Academic Advising Center (AAC) R Center & Applied Sciences Williams Rubenstein Chapel Res. -

History Duke University Was Created in 1924 by James Buchanan Duke As a Memorial to His Father, Washington Duke

History Duke University was created in 1924 by James Buchanan Duke as a memorial to his father, Washington Duke. The Dukes, a Durham family who built a worldwide financial empire in the manufacture of tobacco and developed the production of electricity in the two Carolinas, long had been interested in Trinity College. Trinity traced its roots to 1838 in nearby Randolph County when local Methodist and Quaker communities joined forces to support a permanent school, which they named Union Institute. After a brief period as Normal College (1851-59), the school changed its name to Trinity College in 1859 and affiliated with the Methodist Church. The college moved to Durham in 1892 with financial assistance from Washington Duke and the donation of land by Julian S. Carr. In December 1924, the trustees gratefully accepted the provisions of James B. Duke's indenture creating the family philanthropic foundation, The Duke Endowment, which provided, in part, for the expansion of Trinity College into Duke University. As a result of the Duke gift, Trinity underwent both physical and academic expansion. The original Durham campus became known as East Campus when it was rebuilt in stately Georgian architecture. West Campus, Gothic in style and dominated by the soaring 210-foot tower of Duke Chapel, opened in 1930. East Campus served as home of the Woman's College of Duke University until 1972, when the men's and women's undergraduate colleges merged. Both men and women undergraduates attend Trinity College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Engineering. In 1995, East Campus became the home for all first-year students. -

Orientation Workbook for Transfer Students at Duke University, 2018

DUKET | 2018-19 This belongs to: Contact: 15-50 1 E RWIN ROAD E R W I N R O A D M A R K H A M A V E N U E Branson JB Duke Building Hotel 0 1 & Phytotron Baldwin Environment Hall VA Hospital Biddle Auditorium R. David Thomas Duke MORREENE RD Greenhouses Music 8 5 Art To Duke Forest/Lemur Ctr Executive Softball WXDU Bishop's House Conference CIRCUIT DRIVE CIRCUIT DR Radio Building Bldg. Parking Garage Stadium (Continuing Ed) Center Eye Center NC 15-5 4 Levine Science Research Center French Family T o and I- Hall Fuqua Science Center Hall Bassett Res. Bassett School RESEARCH DRIVE Brookwood Bivins Bldg. Res. Pegram Gross Inn of Law Hall North Bldg FULTON STREET Business School Biolo gical courtyard Physics Benjamin Duke Sciences and Math Engineering Library and Teer Bryan Seeley Statue Academic Advising 1 Engineering Administration Research Bldg Center Hall Hudson Hall Mudd Hall (Searle Ctr) Duke Hospital Brown Res. Brown Alspaugh Res. Alspaugh SCIENCE DRIVE SCIENCE DRIVE NINTH STREET Pratt North Williams Field Medical Athletic Field East Parking Garage Engineering at Jack Katz Memorial Sanford FCIEMAS Center Lilly Campus 18 East Stadium Gym/ Campus Marketplace Dining/ School 20 Parking Brodie Rec Library Store Reynolds Theater, 11 Union 17 Trinity Cafe 2 19 Garage Center Griffith Theater BROAD STREET E University Fitzpatrick Center Tennis Courts V Mary Trent Semans I Bryan Jack Coombs for Interdisciplinary Inn Washington R Student Bookstore Medical Education Hall D Center Duke Inn Stadium Wellness Engineering, Medicine, Bell Tower s. D 5 Building Academic Advising Center (AAC) R Center & Applied Sciences Williams Rubenstein Chapel Res. -

Event Archives August 2016

Event Archives August 2016 - July 2017 Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations Events at Duke, Events at UNC, Events in the Triangle August 10, 2016 Perceptions, Realities and the Changing Dynamics of Pakistan Relations: A Lecture by Dr. Saeed Shafqat Time: 3:00pm – 4:35pm Location: FedEx Global Education Center UNC-Chapel Hill Categories: Lecture Description: U.S.- Pakistan relations are a painfully enduring relationship. Over the decades, these nations have witnessed high and low points several times yet endured and not broken. The ‘terms of endearment’ have undergone changes during each decade. For example, former Secretary of State Hilary Clinton described US-Pakistan relations as ‘transactional’ and not based on mutual trust. Some scholars have declared Pakistan an ‘unworthy ally.’ Others have announced the ‘end of illusions’, yet others claim that India-Pakistan has been ‘de- hyphenated’ in the U.S. South Asia strategy and yet India-Pakistan relations remain a major concern for the U.S. Why? To borrow a Chinese expression, this is the ‘New Normal’ in U.S.- Pakistan relations. Focusing on three dimensions–geo-strategic interests, the global war on terrorism and a changing regional environment–policy makers in the two countries are constantly trying to re- position and adapt on issues of mutual concern. These sensibilities are manifested through the ongoing Strategic Dialogue between the two countries, despite hiccups. Interpreting patterns of ‘high’ and ‘low’ points, Dr. Saeed Shafqat will identify the changing contours and future direction of U.S.-Pakistan relations. Sponsors: This event is sponsored by Wake Forest University, North Carolina Central University and the Carolina Asia Center. -

Friday, April 28, 2017 7:30 AM to 3:30 PM Fitzpatrick Center Duke

KURe and PMRC Duke Multidisciplinary K12 Urologic Research Career Development Program (KURe) Pelvic Medicine Research Consortium (PMRC) Friday, April 28, 2017 7:30 AM to 3:30 PM Fitzpatrick Center Duke University Medical Center Durham, North Carolina KURe and PMRC Research Day 2017 Agenda 7:30 - 8:10 AM Registration and Poster Viewing Coffee, Tea, Light Breakfast 8:10 - 8:20 AM Welcome and Introductions, Cindy Amundsen, MD, KURe PI and PD 8:20 - 9:10 AM Moderators: Nazema Y. Siddiqui, MD, MHSc and Patrick C. Seed, MD, PhD Keynote Speaker Suzanne Groah, MD; Georgetown University. “Advancing Care of Urinary Symptoms and Urinary Tract Infection: A Winding Path to Discovery” 9:10 - 9:40 AM Moderator: Matthew O. Fraser, PhD Oral Trainee Presentations 9:10 AM Best Basic/Translational Abstract: Eric Gonzalez, PhD Duke University “Detrusor Underactivity in an Obese-Prone Rat Model” 9:25 AM Best Clinical Science Abstract: Ruiyang Jiang, MD Duke University “The Utility of Charlson-Comorbidity, Van Wairaven and Rhee Index in Predicting post-operative Complications in Pediatric Urology” 9:40 - 10:30 AM Poster Session-1 (odd numbered posters) and Refreshments 10:30 -11:30 AM Moderators: Monique Vaughan, MD and Megan Bradley, MD Panel Discussion “Inflammation/Infection/UTI” Panelists: Jonathan Barasch, MD, PhD, Nephrology, Columbia University Suzanne Groah, MD, Rehabilitative Medicine, Georgetown Univ. Patrick C. Seed, MD, PhD, UTI/ Infectious Disease, Northwestern Todd Purves, MD, AB, PhD, Urology, Duke University Ann Stapleton, MD, Infectious Disease, University of Washington 11:30 -12:30 PM Lunch with the Experts 12:30 - 1:15 PM Poster Session-2 (even numbered posters) 1:15 - 2:15 PM Moderators: Brian Inouye, MD and Jim A. -

VITA-Full Nov 2019

November 2019 CATHY N. DAVIDSON Founding Director, The Futures Initiative Distinguished Professor of English and MA Program in Digital Humanities MS Program in Data Analysis and Visualization The Graduate Center, CUNY 365 Fifth Avenue, Room 3314 New York, NY 10016-4309 [email protected] Ruth F. DeVarney Professor Emerita of Interdisciplinary Studies, Duke University Co-Founder and Co-Director, HASTAC (hastac.org) http://www.cathydavidson.com EDUCATION Postdoctoral study, The University of Chicago, 1975-1976; in linguistics and literary theory Ph.D., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1974; in English M.A., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1973; in English B.A., Elmhurst College, 1970; in philosophy (logic) and English HONORARY DEGREES Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters, Elmhurst College, 1989 Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters, Northwestern University, 2005 EMPLOYMENT The Graduate Center, CUNY July 2014- Founding Director, Futures Initiative; Distinguished Professor of English, MA in Digital Humanities and MS in Data Analysis and Visualization Duke University July 2014-2017 Ruth F. DeVarney Professor Emerita of Interdisciplinary Studies and Distinguished Visiting Professor 2012-2014 Founder and Co-Director, Ph.D. Lab in Digital Knowledge 2006-2014 John Hope Humanities Institute Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies and DeVarney Professor of English 1998-2006 Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies 1999-2003 Co-Founder and Co-Director, John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute 1996-2014 Distinguished Professor