Inventing Cinema Inventing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4K Resolution Is Ready to Hit Home

4K RESOLUTION 4K Resolution is ready to Hit Home 4K that became a digital cinema standard in 2005 is now recognized as the next high quality image technology of HD in the market. With a growing selection of 4K televisions and recent announcements of affordable cinema-style camcorders, 4K resolution is poised to become a new standard. VIVEK KEDAR 011 was a year of Tablets and mobile. - Hacktivism On one side where we saw new - 4G LTE technologies emerging, mobile devices became way more powerful than they 4K Buzzword 2were. TVs got better but their LG, Samsung and several others would showcase Technologies, especially, 3D, remained their 2012 range of products at CES 2012. The proprietary. major buzz this year would be about the 3D 4K TVs. 2012 would be all about: Not only these TVs would be large (~60″ they - Quad core Tablets, Mobile Phones would deliver super high definition content with a - 3D TVs with 4k resolution (4096x) smooth picture (~200hz and above). - Mobile payments One of the first companies to embrace the - Rise of NextGen Social networking resolution craze was Oakley founder Jim Jannard's 4K RESOLUTION company, RED DIGITAL CINEMA. In 2007, they strong need of building integrated and distributed released a new camcorder called the RED One that environment for high resolution applications. could shoot at 4K resolutions for a much lower In simple words, the 4K is the resolution of 8-9 MPix price than comparable 4K camcorders. Then, in having about 4 thousands points horizontally. The 2011, the EPIC camera upped the resolution even resolution often depends on the screen aspect further to 5K. -

American Society of Cinematographers Motion Imaging Technology Council Progress Report 2018

American Society of Cinematographers Motion Imaging Technology Council Progress Report 2018 By Curtis Clark, ASC; David Reisner; David Stump, Color Encoding System), they can creatively make the ASC; Bill Bennett, ASC; Jay Holben; most of this additional picture information, both color Michael Karagosian; Eric Rodli; Joachim Zell; and contrast, while preserving its integrity throughout Don Eklund; Bill Mandel; Gary Demos; Jim Fancher; the workflow. Joe Kane; Greg Ciaccio; Tim Kang; Joshua Pines; Parallel with these camera and workflow develop- Pete Ludé; David Morin; Michael Goi, ASC; ments are significant advances in display technologies Mike Sanders; W. Thomas Wall that are essential to reproduce this expanded creative canvas for cinema exhibition and TV (both on-demand streaming and broadcast). While TV content distribu- ASC Motion Imaging Technology Council Officers tion has been able to take advantage of increasingly avail- Chair: Curtis Clark, ASC able consumer TV displays that support (“4K”) Ultra Vice-Chair: Richard Edlund, ASC HD with both wide color gamut and HDR, including Vice-Chair: Steven Poster, ASC HDR10 and/or Dolby Vision for consumer TVs, Dolby Secretary & Director of Research: David Reisner, Vision for Digital Cinema has been a leader in devel- [email protected] oping laser-based projection that can display the full range of HDR contrast with DCI P3 color gamut. More recently, Samsung has demonstrated their new emissive Introduction LED-based 35 foot cinema display offering 4K resolu- ASC Motion Imaging Technology Council Chair: tion with full HDR utilizing DCI P3 color gamut. Curtis Clark, ASC Together, these new developments enable signifi- cantly enhanced creative possibilities for expanding The American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) the visual story telling of filmmaking via the art of Motion Imaging Technology Council (MITC – “my cinematography. -

THE STATUS of CINEMATOGRAPHY TODAY the Status of Cinematography Today

THE STATUS OF CINEMATOGRAPHY TODAY The Status of Cinematography Today HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON THE lenses. Both the Sony F900 with on-board HDCam recording and TRANSITION TO DIGITAL MOTION PICTURE the Thomson Viper tethered to an external SRW 5500 studio deck CAMERAS were used to shoot the night scenes for Collateral. The F900 was Curtis Clark, ASC selected only for those scenes where the camera setup required un- restricted mobility free from being tethered to an external recorder. A Controversial Beginning Although Digital Intermediate workflow and Digital Cinema exhi- bition were both in the early stages of implementation, the advent As anyone involved with feature film and/or TV production knows, of DI-based post workflows facilitated an easier integration of digi- cinematography has recently been experiencing acceleration in the tally captured images, especially when combined with film scans routine use of digital motion picture cameras as viable alternatives that were usually 2K 10-bit DPX. to shooting with film. The beginning of this transitional process Mann’s widely publicized desire to reproduce extremely challeng- started with George Lucas in April 2000. ing shadow detail in the nighttime scenes was effectively realized When Lucas received the first 24p Sony F900 HD camera to shoot via the digital cameras’ ability to handle that creative challenge Star Wars Episode II, Attack of the Clones, cinematography was intro- at low light level exposures better than film could. The brighter duced to what was the beginning of perhaps the most disruptive mo- daytime scenes were shot on film, which was better able to repro- tion imaging technology in the history of motion picture production. -

Red Scarlet Operation Guide

RED SCARLET-X® OPERATION GUIDE build v3.2 www.red.com THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............... 1 Module Installation / MAIN MENU ................................ 67 DISCLAIMER ................................. 3 Removal ............................... 29 FPS .......................................... 67 Copyright Notice ........................ 3 REDMOTE ................................ 33 Varispeed ............................ 67 Trademark Disclaimer ................ 3 Displays .................................... 35 Basic Settings ..................... 68 COMPLIANCE ............................... 4 BOMB EVF and Bomb EVF Advanced Settings .............. 68 Industrial Canada Emission (OLED) ...................................... 35 ISO (Sensitivity) ........................ 69 Compliance Statements ............ 4 Touchscreen LCD .................... 37 F Stop ...................................... 69 Federal Communications BASIC OPERATION ..................... 38 Exposure .................................. 71 Commission (FCC) Power Sources ......................... 38 Basic Settings ..................... 71 Statement .................................. 4 Side Handle ......................... 38 Advanced Settings .............. 72 Australia and New Zealand Quad Battery Module .......... 39 White Balance .......................... 74 Statement .................................. 5 REDVOLT and REDVOLT Basic Settings ..................... 74 Japan Statements ...................... 5 XL ....................................... -

Demographics Report I 2 Geographic Breakdown Overview

DEMOGRAPHICS 20REPORT 19 2020 Conferences: April 18–22, 2020 Exhibits: April 19–22 Show Floor Now Open Sunday! 2019 Conferences: April 6–11, 2019 Exhibits: April 8–11 Las Vegas Convention Center, Las Vegas, Nevada USA NABShow.com ATTENDANCE HIGHLIGHTS OVERVIEW 27% 63,331 Exhibitors BUYERS 4% Other 24,896 91,921 TOTAL EXHIBITORS 69% TOTAL NAB SHOW REGISTRANTS Buyers Includes BEA registrations 24,086 INTERNATIONAL NAB SHOW REGISTRANTS from 160+ COUNTRIES Full demographic information on International Buyer Attendees on pages 7–9. 1,635* 963,411* 1,361 EXHIBITING NET SQ. FT. PRESS COMPANIES 89,503 m2 *Includes unique companies on the Exhibit Floor and those in Attractions, Pavilions, Meeting Rooms and Suites. 2019 NAB SHOW DEMOGRAPHICS REPORT I 2 GEOGRAPHIC BREAKDOWN OVERVIEW ALL 50 STATES REPRESENTED U.S. ATTENDEE BREAKDOWN 160+ COUNTRIES REPRESENTED 44% Pacific Region 19% Mountain Region 16% Central Region 21% New England/Mid and South Atlantic 24% 26% 30% NON-U.S. ATTENDEE BREAKDOWN 26% Europe 30% Asia 3% 24% N. America (excluding U.S.) 14% 3% 14% S. America 3% Australia 3% Africa 55 45 DELEGATIONS ENROLLED COUNTRIES REPRESENTED BY A DELEGATION COUNTRIESCOUNTRIES REPRESENTEDREPRESENTED Afghanistan Colombia Ethiopia Indonesia Pakistan Thailand Argentina Costa Rica France Ivory Coast Panama Tunisia Benin Democratic Republic Germany Japan Peru Turkey Brazil of Congo Ghana Mexico Russia Uruguay Burkina Faso Dominican Republic Greece Myanmar South Africa Venezuela Caribbean Nations Ecuador Guatemala New Zealand South Korea Chile Egypt Honduras -

Epic Movie, Micro Budget

Adobe Creative Suite 5 Production Premium Success Story Nelson Madison Films Epic movie, micro budget Nelson Madison Films switches from Avid to Adobe® Creative Suite® Production Premium software to create Hollywood-caliber indie feature film What do Japanese gangsters, an Italian proctologist, an Armenian art dealer, and a Nelson Madison Films Delivered hero with a very cool car have in common? They all come together in the modern Glendale, California crime thriller Delivered, directed, produced, and edited by Michael Madison and www.facebook.com/ Linda Nelson of Nelson Madison Films. The movie is the company’s third feature- nelsonmadisonfilms length film project. Slated for completion in September 2010, Delivered relies on www.deliveredmovie.com www.youtube.com/indierights the latest filmmaking technologies, including the RED Digital Cinema camera and Adobe Creative Suite 5 Production Premium software. “We knew that the only way to feasibly produce a long-form project of this caliber on our budget was to go completely tapeless, something that was not supported by the proprietary Avid system we used to rely on,” says Nelson. “To achieve the cinematic quality we wanted, we shot using the RED camera and used Adobe Premiere® Pro, After Effects®, and Photoshop® Extended to edit the film and create the effects.” Shoestring budget The ensemble cast of Delivered features career actors such as Toshi Toda, Robert Rusler, Alana Stewart, and Brian McGuire. It also stars Madison, a theater actor, who graduated from Texas Tech with a concentration in film. Set in the Mojave Desert, the new crime thriller was inspired by films like Bullitt, True Romance, and Vanishing Point. -

San Fernando Valley Business Journal - Printer Friendly Version Page 1 of 2

San Fernando Valley Business Journal - Printer Friendly Version Page 1 of 2 San Fernando Valley Business Journal PRINT | CLOSE WINDOW Manufacturers Bring Out Their High-Tech Gadgets By Mark R. Madler - 10/15/2007 San Fernando Valley Business Journal Staff Panavision Inc. showed its commitment to both the film and digital formats with the new cameras, lenses and recording equipment recently unveiled for industry professionals. Panavision CEO Bob Beitcher, assisted by actors dressed as Marilyn Monroe, Austin Powers and Chewbacca, presented the equipment to a crowd of about 60 people at a VIP lunch Oct. 11 at its headquarters in Woodland Hills. An all-day invitation event for industry insiders took place on Oct. 13. In the past, Panavision had debuted new equipment at industry trade shows, but this year took a different route because of the especially advanced offerings. The company’s new XL2 35mm film camera is already in use by filmmakers. The other products displayed are in the final stages of testing and tweaking as the company does not want to risk the money or reputation of its customers until the equipment is fully tested. “That is the Panavision way,” Beitcher said. The audience was also treated to looks at a series of new anamorphic lenses for film cameras; on board battery brackets for film and digital cameras that eliminate the use of battery belts or cables attached to the camera; a compact zoom lens for digital cameras; and a solid-state recorder for digital cameras that is half the size and weight of the previous model. -

Analysis of RED ONE Digital Cinema Camera and RED Workflow

LiU-ITN-TEK-A--09/019--SE Analysis of RED ONE Digital Cinema Camera and RED Workflow Taraneh Foroughi Mobarakeh 2009-03-06 Department of Science and Technology Institutionen för teknik och naturvetenskap Linköping University Linköpings Universitet SE-601 74 Norrköping, Sweden 601 74 Norrköping LiU-ITN-TEK-A--09/019--SE Analysis of RED ONE Digital Cinema Camera and RED Workflow Examensarbete utfört i medieteknik vid Tekniska Högskolan vid Linköpings universitet Taraneh Foroughi Mobarakeh Handledare Fredrik Averpil Handledare John Johansson Examinator Dag Haugum Norrköping 2009-03-06 Upphovsrätt Detta dokument hålls tillgängligt på Internet – eller dess framtida ersättare – under en längre tid från publiceringsdatum under förutsättning att inga extra- ordinära omständigheter uppstår. Tillgång till dokumentet innebär tillstånd för var och en att läsa, ladda ner, skriva ut enstaka kopior för enskilt bruk och att använda det oförändrat för ickekommersiell forskning och för undervisning. Överföring av upphovsrätten vid en senare tidpunkt kan inte upphäva detta tillstånd. All annan användning av dokumentet kräver upphovsmannens medgivande. För att garantera äktheten, säkerheten och tillgängligheten finns det lösningar av teknisk och administrativ art. Upphovsmannens ideella rätt innefattar rätt att bli nämnd som upphovsman i den omfattning som god sed kräver vid användning av dokumentet på ovan beskrivna sätt samt skydd mot att dokumentet ändras eller presenteras i sådan form eller i sådant sammanhang som är kränkande för upphovsmannens litterära eller konstnärliga anseende eller egenart. För ytterligare information om Linköping University Electronic Press se förlagets hemsida http://www.ep.liu.se/ Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet - or its possible replacement - for a considerable time from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. -

Red Motion Mount Operation Guide

RED MOTION MOUNT OPERATION GUIDE DSMC RED MOTION MOUNT S35 TI PL | DSMC RED MOTION MOUNT S35 TI CANON RED.COM RED MOTION MOUNT OPERATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 APPENDIX B: MOTION MOUNT Compatibility 34 Disclaimer 3 Compatibility Requirements 34 Copyright Notice 3 Compatible PL Lenses and Devices 35 Trademark Disclaimer 3 Incompatible PL Lenses and Devices 37 Compliance Statements 3 Compatible Canon EF Lenses 37 Safety Instructions 5 Non-Linear Editing (NLE) Applications 37 CHAPTER 1: MOTION MOUNT Introduction 7 Variable ND Filter 7 IR Filter and Linear Polarization 7 Soft Shutter 8 Square Shutter 8 MOTION MOUNT Types 8 Hardware and System Requirements 8 Additional Resources 9 CHAPTER 2: MOTION MOUNT Installation 10 Lens Mount Alignment 10 Remove Lens Mounts 11 Install the MOTION MOUNT 13 CHAPTER 3: MOTION MOUNT Operation 15 Access the MOTION MOUNT Menu 15 Neutral Density (ND) 16 MOTION MOUNT Shutter Types 23 Map Keys for MOTION MOUNT Settings 25 CHAPTER 4: MOTION MOUNT Maintenance 26 Storage Instructions 26 Clean MOTION MOUNT Glass 26 CHAPTER 5: Troubleshoot the MOTION MOUNT 28 Camera Does Not Recognize the MOTION MOUNT 28 Irregular Out-of-Focus Bokeh Effects and Flare 29 Double Exposures in Captured Footage 29 APPENDIX A: Technical Specifications 30 DSMC RED MOTION MOUNT S35 Ti PL 30 DSMC RED MOTION MOUNT S35 Ti Canon (Captive) 31 Neutral Density and Shutter Angles 31 Maximum Frame Rates 32 COPYRIGHT © 2019 RED.COM, LLC 955-0013, REV-AB | 2 RED MOTION MOUNT OPERATION GUIDE DISCLAIMER COMPLIANCE STATEMENTS ® RED has made every effort to provide clear and accurate INDUSTRIAL CANADA EMISSION COMPLIANCE STATEMENTS information in this document, which is provided solely for the user’s This device complies with Industry Canada license- exempt RSS information. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.245,314 B2 Jannard Et Al

USOO924,5314B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.245,314 B2 Jannard et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Jan. 26, 2016 (54) VIDEO CAMERA 13/0257; H04N 19/00315; H04N 19/00763; H04N 19/00903; H04N 1/648; H04N 5/225; (71) Applicant: RED.COM, INC. Irvine, CA (US) G06T 7/2006; G06T 3/4015; G06T 9/007 (72) Inventors: James H. Jannard, Las Vegas, NV USPC ................ 348/240.2, 222.1, 223.1, 273–280; (US); Thomas Graeme Nattress, Acton 375/240.2, 240.25, 240.26, 340.29: (CA) 382/166 167 See application file for complete search history. (73) Assignee: RED.COM, Inc., Irvine, CA (US) (56) References Cited (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 3,972,010 A 7/1976 Dolby This patent is Subject to a terminal dis 4,200,889 A 4, 1980 Strobele claimer. (Continued) (21) Appl. No.: 14/485,612 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (22) Filed: Sep. 12, 2014 CA 2831 698 10, 2008 CA 26836.36 1, 2014 (65) Prior Publication Data (Continued) US 2015/OOO2695A1 Jan. 1, 2015 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Related U.S. Application Data (63) Continuation of application No. 13/464,803, filed on 2K Digital Cinema Camera Streamlines Movie and HD Production, May 4, 2012, now Pat. No. 8,872,933, which is a Silicon Imaging Digital Cinema, Press News Releases, Hollywood, continuation of application No. 12/101.882, filed on California, date listed Nov. -

RED ONE™ CAMERA: OPERATIONS GUIDE (Firmware Build 17, Version

RED ONE™ CAMERA: OPERATIONS GUIDE (Firmware Build 17, Version 3.4.1) Sections: Page 1. Before You Start 3 2. Camera Assembly 6 3. Physical Controls 8 4. Theory of Operation 12 5. Basic Operation 19 6. Sensor Menu Controls 26 7. Audio Video Menu Controls 34 8. System Menu Controls 42 Appendix A. Upgrading camera firmware 63 Appendix B. Digital Media Management 65 Appendix C: Input and Output Connectors 69 Appendix D: Post Production 79 Apr 30 2009 Copyright RED Digital Cinema 1 --------------------------------- DISCLAIMER RED has made every effort to provide clear and accurate information in this Operations Guide, which is provided solely for the user’s information. While thought to be accurate, the informa- tion in this document is provided strictly “as is” and RED will not be held responsible for issues arising from typographical errors or user’s interpretation of the language used herein that is dif- ferent from that intended by RED. All safety and general information is subject to change as a result of changes in local, federal or other applicable laws. RED reserves the right to revise this Operations Guide and make changes from time to time in the content hereof without obligation to notify any person of such revisions or changes. In no event shall RED, its employees or authorized agents be liable to you for any damages or losses, direct or indirect, arising from the use of any technical or operational information con- tained in this document. ---------------------------------- 2 Copyright RED Digital Cinema Apr 30 2009 1. Before you start. Congratulations on your purchase of a RED ONE™ camera. -

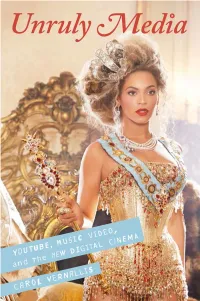

Unruly-Media-Vernallis-C.Pdf

Unruly Media This page intentionally left blank Unruly Media YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema C A R O L V E R N A L L I S 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitt ed by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vernallis, Carol. Unruly media : YouTube, music video, and the new digital cinema / Carol Vernallis.