Durable Solutions for Indigenous Migrants and Refugees in the Context of the Venezuelan Flow in Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogueofbirds1310hell.Pdf

XI E> R.AFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY or ILLINOIS 5^0.5 FI ZOOLOGICAL SERIES FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY FOUNDED BY MARSHALL FIELD, 1893 VOLUME XIII CATALOGUE OF BIRDS OF THE AMERICAS BY CHARLES E. HELLMAYR ASSOCIATE CURATOR OF BIRDS PART X ICTERIDAE WILFRED H. OSGOOD CURATOR, DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY EDITOR PUBLICATION 381 CHICAGO, U.S.A. APRIL 12, 1937 ZOOLOGICAL SERIES FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY FOUNDED BY MARSHALL FIELD, 1893 VOLUME XIII CATALOGUE OF BIRDS OF THE AMERICAS AND THE ADJACENT ISLANDS IN FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY INCLUDING ALL SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES KNOWN TO OCCUR IN NORTH AMERICA, MEXICO, CENTRAL AMERICA, SOUTH AMERICA, THE WEST INDIES, AND ISLANDS OP THE CARIBBEAN SEA, THE GALAPAGOS ARCHIPELAGO, AND OTHER ISLANDS WHICH MAY BE INCLUDED ON ACCOUNT OF THEIR FAUNAL AFFINITIES BY CHARLES E. HELLMAYR ASSOCIATE CURATOR OF BIRDS PART X ICTERIDAE WILFRED H. OSGOOD CURATOR, DEPARTMENT OP ZOOLOGY EDITOR PUBLICATION 381 CHICAGO, U.S.A. APRIL 12, 1937 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY FIELD MUSEUM PRESS v.13 EDITOR'S NOTE As a matter of convenience, the present part of the "Catalogue of the Birds of the Americas" is confined to the treatment of the family Icteridae. As prepared by the author, the manuscript cover- ing this family was included with that of the Fringillidae, and only a single introduction was written. In this, he states that "the families treated are fairly circumscribed, but their further classification offers unusual difficulties. In the case of the Troupials, the author is bound to agree with the late Robert Ridgway's view that splitting into subfamilies serves no practical purpose, since no fast lines can be drawn between the minor groups proposed by certain systematists." Various museums and individuals, as heretofore, have cooperated in the preparation of this part by supplying material and information. -

PDV Bolívar -..::MOVILNET

Puntos de Venta Un1ca Electrónica Estado Bolívar Nombre Ciudad Teléfono Dirección BODEGA LA CASA AMARILLA (LUZ ESTELA ENTRADA DE PARQUES DEL SUR PERIMETRAL SANTA BARBARA GUIZA) CIUDAD BOLIVAR, BOLIVAR 0285-615-6671 CASA Nº6 AVENIDA PERIMETRAL EN LA E/S AL LADO DE BODEGA ARUBA (RADI MORAD NASIR) CIUDAD BOLIVAR, BOLIVAR 0414-895-5369 / 0414-853-6967 BRISAS DEL SUR 1 PERIMETRAL CERCA DE LA AVENIDA ESPAÑA URB. VILLA BETANIA MANZ.6 CASA Nº 26 A 50 MTS. DE PABLO ABASTO HIBER PUERTO ORDAZ, BOLIVAR 0416-8888962 BONALDY CARLOS ESPINOZA (BODEGA MIMI KAR, F.P.) CIUDAD BOLIVAR, BOLIVAR 0426 591 7150 // 0424 928 2844 MARHUANTA AV. PRINCIPAL AL LADO DE CARNICERIA ANAYEN SECTOR EL CENTRO CALLE PIAR EFIC,LA CAMPESINA AL LADO MICROEMPRESA ADELHAI EL PALMAR, BOLIVAR 0288-881-1297 / 0426-796-2829 DEL MERCADO MUNICIPAL ROBLE X DENTRO CALLE 23 DE ENERO CASA NRO 06 DETRAZ DE COMERCIAL URKUPINA, C.A. SAN FELIX, BOLIVAR 0286-931-2981 / 0416-289-5029 LA ESCUELA JOSE ANGEL RUIZ CASCO CENTRAL C/ POLANCO FRENTE A L HOSPITAL GERVACIO MICROEMPRESA MI RINCONCITO UPATA, BOLIVAR 0416-885-5702 VERA CUSTODIO MANUEL CARLOS PIAR CALLE 21 MANZ. 16 FRENTE A LA PLAZA MICROEMPRESA VARIEDADES INTERPRAY UPATA, BOLIVAR 0414-885-6574 / 0288-2210-4428 MANUEL PIAR. SANTA ELENA DE UAIREN, SECTOR SANTA ELENA C/ IKABARU S/N FRENTE AL HOSPITAL COMERCIALIZADORA EYD, C.A. BOLIVAR 0289-808-8075 LUIS ORTEGA MICROEMPRESA INVERSIONES NUEVO SECTOR NACUPAY C/ PRINCIPAL FRENTE A LA ESCUELA MILENIO EL CALLAO, BOLIVAR 0288-4150970, 0414-7650265. BOLIVARIANA NACUPAY ABASTOS CADENILLAS (COMERCIAL YELDAM LA PARAGUA AV. -

<I>Scutellospora Tepuiensis</I>

MYCOTAXON ISSN (print) 0093-4666 (online) 2154-8889 Mycotaxon, Ltd. ©2017 January–March 2017—Volume 132, pp. 9–18 http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/132.9 Scutellospora tepuiensis sp. nov. from the highland tepuis of Venezuela Zita De Andrade1†, Eduardo Furrazola2 & Gisela Cuenca1* 1 Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas (IVIC), Centro de Ecología, Apartado 20632, Caracas 1020-A, Venezuela 2Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, CITMA, C.P. 11900, Capdevila, Boyeros, La Habana, Cuba * Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract—Examination of soil samples collected from the summit of Sororopán-tepui at La Gran Sabana, Venezuela, revealed an undescribed species of Scutellospora whose spores have an unusual and very complex ornamentation. The new species, named Scutellospora tepuiensis, is the fourth ornamented Scutellospora species described from La Gran Sabana and represents the first report of a glomeromycotan fungus for highland tepuis in the Venezuelan Guayana. Key words—arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, taxonomy, tropical species, Gigasporaceae, Glomeromycetes Introduction The Guayana shield occupies a vast area that extends approximately 1500 km in an east-to-west direction from the coast of Suriname to southwestern Venezuela and adjacent Colombia in South America. This region is mostly characterized by nutrient-poor soils and a flora of notable species richness, high endemism, and diversity of growth forms (Huber 1995). Vast expanses of hard rock (Precambrian quartzite and sandstone) that once covered this area as part of Gondwanaland (Schubert & Huber 1989) have been heavily weathered and fragmented by over a billion years of erosion cycles, leaving behind just a few strikingly isolated mountains (Huber 1995). These table mountains, with their sheer vertical walls and mostly flat summits, are the outstanding physiographic feature of the Venezuelan Guayana (Schubert & Huber 1989). -

The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America Volume 11 Article 1 Issue 1 Volume 11, Issue 1 6-2013 The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin Andrés Pablo Salanova University of Ottawa Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Epps, Patience and Salanova, Andrés Pablo (2013). "The Languages of Amazonia," Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 1, 1-28. Available at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epps and Salanova: The Languages of Amazonia ARTICLE The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin Andrés Pablo Salanova University of Ottawa Introduction Amazonia is a linguistic treasure-trove. In this region, defined roughly as the area of the Amazon and Orinoco basins, the diversity of languages is immense, with some 300 indigenous languages corresponding to over 50 distinct ‘genealogical’ units (see Rodrigues 2000) – language families or language isolates for which no relationship to any other has yet been conclusively demonstrated; as distinct, for example, as Japanese and Spanish, or German and Basque (see section 12 below). Yet our knowledge of these languages has long been minimal, so much so that the region was described only a decade ago as a “linguistic black box" (Grinevald 1998:127). -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Venezuela: Indigenous Peoples Face Deteriorating Human Rights Situation Due to Mining, Violence and COVID-19 Pandemic

Venezuela: Indigenous peoples face deteriorating human rights situation due to mining, violence and COVID-19 pandemic Venezuela is suffering from an unprecedented human rights and humanitarian crisis that has deepened due to the dereliction by the authoritarian government and the breakdown of the rule of law in the country. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has estimated that some 5.2 million Venezuelans have left the country, most arriving as refugees and migrants in neighbouring countries. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in 2018 had categorized this situation of human rights, as “a downward spiral with no end in sight”. The situation of the right to health in Venezuela and its public health system showed structural problems before the pandemic and was described as a “dramatic health crisis (…) consequence of the collapse of the Venezuelan health care system” by the High Commissioner. Recently, the OHCHR submitted a report to the Human Rights Council, in which it addressed, among other things the attacks on indigenous peoples’ rights in the Arco Minero del Orinoco (Orinoco’s Mining Arc or AMO). Indigenous peoples’ rights and the AMO mining projects before the covid-19 pandemic Indigenous peoples have been traditionally forgotten by government authorities in Venezuela and condemned to live in poverty. During the humanitarian crisis, they have suffered further abuses due to the mining activity and the violence occurring in their territories. In 2016, the Venezuelan government created the Orinoco’s Mining Arc National Strategic Development Zone through presidential Decree No. 2248, as a mega-mining project focused mainly in gold extraction in an area of 111.843,70 square kilometres. -

'Culture Collecting': Examples from the Study of South American (Fire)

The Cracks, Bumps, and Dents of ‘Culture Collecting’: Examples from the Study of South American (Fire) Fans As rachaduras, solavancos e amolgadelas da ‘coleta de cultura’: exemplos do estudo dos abanos (para fogo) sul-americanos Konrad Rybka Leiden University, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract: Ethnography, a means of representing the culture of a people graphically and in writing, as well as ethnographic museums, institutions devoted to conserving, contextualizing, and displaying indigenous heritage for wider audiences, strive to portray cultures adequately and on their own terms. However, given that the ethnographic enterprise has virtually always been carried out by and within non-indigenous scientific structures, its products are at a high risk of being tinged by the Western lens, in particular Western scientific theory and practice. This article focuses on the ethnographic record of South American fire fans – defined by ethnographers as tools for fanning cooking fires – to demonstrate how such biases can be removed by taking stock of the entirety of the relevant ethnographic heritage and analyzing it through the prism of the documented practices in which such objects are enmeshed, including the very practice of ethnography. In the light of such practices, the ethnographic record of fire fans deconstructs into a corpus of historical documents revealing the momentary, yet meaningful, technological choices made by the indigenous craftsmen who produced the objects and exposing Western categories, Kulturkreise mentality, and culture-area schemata imposed on them. Keywords: collection; fire fans; Lowland South America. Resumo: A etnografia, enquanto meio de representar a cultura de um povo graficamente e por escrito, bem como os museus etnográficos, instituições dedicadas a conservar, contextua- lizar e exibir o patrimônio indígena para um público mais amplo, se esforçam para retratar as culturas de forma adequada e em seus próprios termos. -

The State of Venezuela's Forests

ArtePortada 25/06/2002 09:20 pm Page 1 GLOBAL FOREST WATCH (GFW) WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE (WRI) The State of Venezuela’s Forests ACOANA UNEG A Case Study of the Guayana Region PROVITA FUDENA FUNDACIÓN POLAR GLOBAL FOREST WATCH GLOBAL FOREST WATCH • A Case Study of the Guayana Region The State of Venezuela’s Forests. Forests. The State of Venezuela’s Págs i-xvi 25/06/2002 02:09 pm Page i The State of Venezuela’s Forests A Case Study of the Guayana Region A Global Forest Watch Report prepared by: Mariapía Bevilacqua, Lya Cárdenas, Ana Liz Flores, Lionel Hernández, Erick Lares B., Alexander Mansutti R., Marta Miranda, José Ochoa G., Militza Rodríguez, and Elizabeth Selig Págs i-xvi 25/06/2002 02:09 pm Page ii AUTHORS: Presentation Forest Cover and Protected Areas: Each World Resources Institute Mariapía Bevilacqua (ACOANA) report represents a timely, scholarly and Marta Miranda (WRI) treatment of a subject of public con- Wildlife: cern. WRI takes responsibility for José Ochoa G. (ACOANA/WCS) choosing the study topics and guar- anteeing its authors and researchers Man has become increasingly aware of the absolute need to preserve nature, and to respect biodiver- Non-Timber Forest Products: freedom of inquiry. It also solicits Lya Cárdenas and responds to the guidance of sity as the only way to assure permanence of life on Earth. Thus, it is urgent not only to study animal Logging: advisory panels and expert review- and plant species, and ecosystems, but also the inner harmony by which they are linked. Lionel Hernández (UNEG) ers. -

Peoples in the Brazilian Amazonia Indian Lands

Brazilian Demographic Censuses and the “Indians”: difficulties in identifying and counting. Marta Maria Azevedo Researcher for the Instituto Socioambiental – ISA; and visiting researcher of the Núcleo de Estudos em População – NEPO / of the University of Campinas – UNICAMP PEOPLES IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZONIA INDIAN LANDS source: Programa Brasil Socioambiental - ISA At the present moment there are in Brazil 184 native language- UF* POVO POP.** ANO*** LÍNG./TRON.**** OUTROS NOMES***** Case studies made by anthropologists register the vital events of a RO Aikanã 175 1995 Aikanã Aikaná, Massaká, Tubarão RO Ajuru 38 1990 Tupari speaking peoples and around 30 who identify themselves as “Indians”, RO Akunsu 7 1998 ? Akunt'su certain population during a large time period, which allows us to make RO Amondawa 80 2000 Tupi-Gurarani RO Arara 184 2000 Ramarama Karo even though they are Portuguese speaking. Two-hundred and sixteen RO Arikapu 2 1999 Jaboti Aricapu a few analyses about their populational dynamics. Such is the case, for RO Arikem ? ? Arikem Ariken peoples live in ‘Indian Territories’, either demarcated or in the RO Aruá 6 1997 Tupi-Mondé instance, of the work about the Araweté, made by Eduardo Viveiros de RO Cassupá ? ? Português RO/MT Cinta Larga 643 1993 Tupi-Mondé Matétamãe process of demarcation, and also in urban areas in the different RO Columbiara ? ? ? Corumbiara Castro. In his book (Araweté: o povo do Ipixuna – CEDI, 1992) there is an RO Gavião 436 2000 Tupi-Mondé Digüt RO Jaboti 67 1990 Jaboti regions of Brazil. The lands of some 30 groups extend across national RO Kanoe 84 1997 Kanoe Canoe appendix with the populational data registered by others, since the first RO Karipuna 20 2000 Tupi-Gurarani Caripuna RO Karitiana 360 2000 Arikem Caritiana burder, for ex.: 8,500 Ticuna live in Peru and Colombia while 32,000 RO Kwazá 25 1998 Língua isolada Coaiá, Koaiá contact with this people in 1976. -

Roraima State Site Profiling. Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State

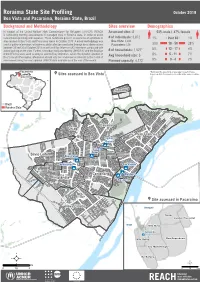

Roraima State Site Profiling October 2018 Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State, Brazil Background and Methodology Sites overview Demographics In support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), REACH Assessed sites: 8 53% male / 47% female 1+28+4+7+7 is conducting monthly assessments in managed sites in Roraima state, in order to assist 1+30+5+8+9 humanitarian planning and response. These factsheets present an overview of conditions in # of individuals: 3,872 1% 0ver 60 1% sites located in Boa Vista and Pacaraima towns in October 2018. A mixed methodology was Boa Vista: 3,444 used to gather information, with primary data collection conducted through direct observations Pacaraima: 428 30% 18 - 59 28% between 29 and 30 of October 2018 as well as 8 Key Informant (KI) interviews conducted with 5% 12 - 17 4% actors working on the sites. Further, secondary data provided by UNHCR KI and the Brazilian # of households: 1,527* Armed Forces were used to analyse selected key indicators. Given the dynamic situation in Avg household size: 3 8% 5 - 11 7% Boa Vista and Pacaraima, information should only be considered as relevant to the month of assessment using the most updated UNHCR data available as of the end of the month. Planned capacity: 4,172 9% 0 - 4 7% !(Pacaraima *Estimated by assuming an average household size, !( ¥Sites assessed in Boa Vista based on data from previous rounds in the same location. Boa Vista Cauamé Brazil Roraima State Cauamé União São Francisco Jardim Floresta ÔÆ Tancredo Neves Silvio Leite Nova Canaã ÔÆ ÔÆ Pintolândia São Vicente ÔÆ ÔÆ ÔÆ Centenário ÔÆ Rondon 1 Pintolândia Rondon 3 ¥Site assessed in Pacaraima Nova Cidade Venezuela Suapi Jardim Florestal Brazil Vila Nova Janokoida ÔÆ Das Orquídeas Vila Velha Ilzo Montenegro Da Balança ² ² km m 0 1,5 3 0 500 1.000 Fundo de População das Nações Unidas União Europeia Roraima site profiling October 2018 Jardim Floresta Boa Vista, Roraima State, Brazil Lat. -

CRACKDOWN on DISSENT Brutality, Torture, and Political Persecution in Venezuela

CRACKDOWN ON DISSENT Brutality, Torture, and Political Persecution in Venezuela HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Crackdown on Dissent Brutality, Torture, and Political Persecution in Venezuela Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-35492 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit: http://www.hrw.org The Foro Penal (FP) or Penal Forum is a Venezuelan NGO that has worked defending human rights since 2002, offering free assistance to victims of state repression, including those arbitrarily detained, tortured, or murdered. The Penal Forum currently has a network of 200 volunteer lawyers and more than 4,000 volunteer activists, with regional representatives throughout Venezuela and also in other countries such as Argentina, Chile, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Uruguay, and the USA. Volunteers provide assistance and free legal counsel to victims, and organize campaigns for the release of political prisoners, to stop state repression, and increase the political and social cost for the Venezuelan government to use repression as a mechanism to stay in power. -

57Th DIRECTING COUNCIL 71St SESSION of the REGIONAL COMMITTEE of WHO for the AMERICAS Washington, D.C., USA, 30 September-4 October 2019

57th DIRECTING COUNCIL 71st SESSION OF THE REGIONAL COMMITTEE OF WHO FOR THE AMERICAS Washington, D.C., USA, 30 September-4 October 2019 Provisional Agenda Item 7.7 CD57/INF/7 30 August 2019 Original: English PAHO’S RESPONSE TO MAINTAINING AN EFFECTIVE TECHNICAL COOPERATION AGENDA IN VENEZUELA AND NEIGHBORING MEMBER STATES Background 1. The Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, a federal republic with more than 30 million inhabitants, has been facing a sociopolitical and economic situation that has negatively impacted social and health indicators. 2. Outbreaks of diphtheria, measles, and malaria have spread rapidly, affecting many of the country’s 23 states and the Capital District simultaneously. Other public health concerns include increases in tuberculosis cases and in maternal and infant mortality (1), as well as issues around mental health and violence prevention.1 A further concern is the limited access to medicines, adequate nutrition, and adequate care for people with life- threatening acute and chronic conditions, including people living with HIV. 3. There have been intensified population movements both within the country and to other countries, particularly Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, and Trinidad and Tobago. Since 2017, an estimated 4 million Venezuelans have migrated to other countries, including an estimated 3.3 million who have gone to other Latin America and Caribbean countries: 1.3 million to Colombia, 806,900 to Peru, 288,200 to Chile, 263,000 to Ecuador, 168,400 to Brazil, 145,000 to Argentina, 94,400 to Panama, 40,000 to Trinidad and Tobago, 39,500 to Mexico, and 36,400 to Guyana, among others (figures as of July 2019) (2).