KEW COMMUNITY TRUST and the AVENUE CLUB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Trustees Report 10/11

IMPACT REPORT 2014 - 2015 SPEAR Impact Report 2014 – 15 1 | P a g e Contents Letter from the Chair and Chief Executive 3 Part 1: an overview Our strategy 4 Our purpose, approach and values 4 Homelessness: a problem that isn’t going away 5 Highlights of 2014/15 6 New service developments: continuing our pioneering role 7 Community involvement: how SPEAR is spreading the word 8 Part 2: a closer look at key areas of our work Working with young people 9 Working with women 9 Promoting health and wellbeing 10 Progression to employment 11 Partnering in community safety 12 Running a volunteering programme 13 Thanks from SPEAR 14 SPEAR Impact Report 2014 – 15 2 | P a g e Letter from the Chair and Chief Executive SPEAR has continued to build its effective and unique response to increased street homelessness. We have seen a further increase in the number of people sleeping rough this year and a steep increase in the number of people struggling with other types of homelessness. The proportion of our clients with complex health and social care needs has increased again and we are concerned by the rising number of street homeless women and young people in our services. In a context of continued funding cuts across the homelessness sector, we are pleased that our income has remained consistent this year. This allows us to continue to deliver our strategic aims of helping the most vulnerable people in our community effectively – people who have often failed to engage with alternative support and who struggle to access mainstream services. -

Thursday 18 June 2020

Thursday 18 June 2020 Dear Friends, You will have heard the government announcement that churches may reopen for private prayer as well as for funerals from 15 June onwards. We are working through all the guidance that is being published about how to open churches safely and how to keep members of our congregations safe. This is important and can’t be rushed. This week St Mary Magdalene will reopen for the first time on Saturday, 20 June, between 10.00am and 12.00noon. After this week, St John the Divine and St Matthias will also start opening their doors. We will publish more details in next week’s newsletter. In the meantime, do continue with prayers for our church communities and join in worship via Zoom or Facebook! St Matthias are holding their Sunday worship via zoom every Sunday at 10.00am – please contact Anne for access codes. St John the Divine and St Mary Magdalene post recorded services on the churches’ Facebook pages and then also on the Richmond Team Ministry website. Details about Morning Prayer are further down in this newsletter. The annual St Alban’s Pilgrimage is a wonderful celebration of the life of England’s first martyr Alban and a fantastic day for pilgrims from all over the country, including Richmond. Sadly the day had to be cancelled this year, but there will be an online version called The Alban Pilgrimage Reimagined on 21 June 10.00am via YouTube, with Revd Richard Coles, parish priest, broadcaster and former Communard, and other special guests. Our prayers at St John the Divine this week are particularly for the repose of the soul of Kay Stangroom. -

ALMSHOUSE NEWS SPRING 2019 the Quarterly Newsletter for the Richmond Charities Almshouses ______Stories for the Soul by Stuart

ALMSHOUSE NEWS SPRING 2019 The quarterly newsletter for the Richmond Charities Almshouses __________________________________________________________ Stories for the Soul by Stuart Mrs Carmel Regan (2 Michel’s) and Mrs Cathy Widger (7 Hickey’s). ************************************** Chapel Diary (Special Services and Events) by Stuart Wednesday 6th March at 11am: Eucharist with hymns for Ash Wednesday. During the period of Lent this Wednesday 13th, 20th, & 27th year we will be preparing for the March and 3rd, 10th April at 10am: celebrations of Easter with some Stories for the Soul (in the Green ‘Stories for the Soul’. Stuart will be Room). sharing these stories in the Green Room on Wednesday mornings with Thursday 18th April at 6pm: plenty of opportunity for reflective Eucharist of the Last Supper with wondering together, a chance for a hymns for Maundy Thursday. little craft activity and some delicious treats over coffee. Friday 19th April at 2pm: Liturgy of the Cross with hymns for Good Friday. The stories are drawn from the parables of Jesus, spiritually and Sunday 21st April at 10.30am: politically challenging stories which Celebration of the Resurrection and invite us to imagine a different sort of First Eucharist of Easter with hymns. world and a very different way of living. Dates and times appear in the diary. Nordic Walking by Stuart William Shakespeare by Richard Howard Nordic Walking ... not just for Norwegians! Over the last few months you may have seen groups of residents marching around with walking poles. This has been as part of a course of lessons by Nordic walking training instructor Rosie Cooke. Nordic walking is a full-body exercise that is easy on the joints and William Shakespeare comes to suitable for all ages and fitness levels. -

Twickenham Edition

The regular newsletter for The Richmond Charities Almshouses March ONE 2021 Welcome to your Almshouse News SPOTLIGHT ON Turner’s House TWICKENHAM DURING LOCKDOWN 2021 News Resident Views Crossword Local Highlights Poetry TWICKENHAM Serge’s Walk Travel Quiz EDITION Eel Pie Island ALMSHOUSE NEWS - Contents Contents Letter from the Chief Executive Letter from the Chief Executive 2-3 by Juliet Ames- News 4-6 Lewis SPOTLIGHT ON TWICKENHAM Roadmap out of lockdown for our What I Love About Twickenham 7 community Helpful Twickenham Organisations 8 I’m sure you will all have read or heard History of Eel Pie 9 about the government’s roadmap out of lockdown, published on 22 February. What Does Twickenham Offer 10-11 Now that we have a clearer sense of the road ahead, we can start also to Community Life 12 tentatively plan our own community’s roadmap out of lockdown. Staff and I Serge’s Twickenham Walk 13-16 are working on this and we will hope to share with you soon information about Turner’s House 17 what sorts of events and activities we may be able to organise which fit with A Good Place to Call Home 18-19 the government’s 4 stages of easing lockdown. The government’s dates are, Twickenham Map Highlights 20-21 as they have said, the earliest dates on which these stages of easing lockdown Travel Quiz 22-23 will take place, and the government Crossword Competition 24-25 could push them back if their 4 tests (on vaccinations, reducing hospitalisations, Answer Page 26 infection rates and new variants of covid-19) are not met. -

Almshouse Accommodation

Almshouse Accommodation richmondcharities.org.uk Registered Charity No. 200431 The Richmond Charities provides a vibrant, friendly and caring community where older people are encouraged to live full and active lives within the setting of high quality housing, support, comfort and security. Benn’s Walk Bishop Duppa’s Almshouses Candler Almshouses Church Estate Almshouses Hickey’s Almshouses Houblon’s Almshouses Manning Place Michel’s Almshouses Queen Elizabeth’s Almshouses The Richmond Charities manages 130 almshouses on nine estates in Richmond and Twickenham. The smallest estate has just four almshouses and the largest over fifty. Each almshouse estate is part of the larger community of The Richmond Charities. The Richmond Charities has been providing almshouse accommodation in the borough for over 400 years. 2 Independent living within a supportive environment Almshouse accommodation is available to people resident in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames who are over the age of 65, who are able to live independently and who have a clear financial or social need for the extensive range of support which we offer. We provide self-contained almshouses which are refurbished to a high standard before new residents move in. The Richmond Charities values and ethos make it clear that the charity has a broader vision than simply the provision of housing. Trustees, staff and residents commit to demonstrating the following values in our working and living together: • That we have a preference for those who might be disadvantaged or in housing need. • That we have respect for the whole person: their physical, emotional, social, mental and spiritual well-being. -

4Pm Fair 10Am Fair 2019, Friday 4 October

FULLFULL OFOF LIFELIFE TWICKENHAM TWICKENHAM RFU STADIUM TW2 7BA WHITTON ROAD - 4PM FAIR 10AM FAIR 2019, FRIDAY 4 OCTOBER 020 8891 1411 REGISTER FROM MONDAY 2 SEPTEMBER www.richmond.gov.uk/full_of_life FOR FREE OVER 20 RESIDENTS OVER 80 CAFÉ AND ACTIVITIES AGED 55+ STALLS LUNCH* The free café is available to all visitors. Lunch is for local residents only and on a first-come, first-served basis. Pre-booking is required. Richmond Council Civic Centre 44 York Street Twickenham TW1 3BZ September 2019 Dear Residents, On behalf of Richmond upon Thames Council, I would like to invite you to attend the Council’s annual Full of Life Fair on Friday 4 October 2019. This free event will take place at Twickenham Rugby Stadium. The Stadium is located on Whitton Road, Twickenham, TW2 7BA (map and transport options included in this brochure). The fair will be open from 10am – 4pm. In addition to celebrating the huge contribution older residents make to the borough, the aim of the fair is to provide up-to-date useful information about the local services, activities and organisations available to residents and carers. Those attending will have the opportunity to seek advice from local professionals about health, social care, and how to get involved in local community and activity groups. REGISTRATION You are welcome to join us for the whole day as we have plenty of stalls for you to visit and activities for you to take part in, as well as our free café and lunch. Registration is essential if you wish to attend between 10am-12pm. -

Edition 0235

Est 2016 London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Edition 235 Contents TickerTape TwickerSeal C0VID-19 Borough View A link to the past Marble Hill Marvels Platt’s Eyot Fire Ham Youth Centre Letters Tribune Snippets Scams, Scams, Scams WIZ Tales - Montserrat Twickers Foodie ITALY – From Top To Bottom Traveller’s Tales Review Film Screenings Football Focus Florence Nightingale Day Contributors TwickerSeal Graeme Stoten Simon Fowler Marble Hill House Achieving For Children Strawberry Hill House Francis McInerny Teddington Society Alison Jee Michael Gatehouse Mark Aspen Doug Goodman World InfoZone Shona Lyons Bruce Lyons St Mary’s University Richmond Film Society James Dowden RFU LBRuT WHO Editors Berkley Driscoll Teresa Read 7th May 2021 Radnor Gardens Photo by Berkley Driscoll TickerTape - News in Brief Bus Strike Suspended The proposed industrial action, which was due to disrupt a number of bus routes in west and south west London, and parts of Surrey on Friday 7 and Saturday 8 May, has been suspended. Bus routes in these areas will now run as normal. District Line Suspension No service between Earl’s Court and Richmond/Ealing Broadway on Saturday 8 and Sunday 9 May. Rail replacement buses will run. London Overground Suspension No service between South Acton and Richmond on Saturday 8 and Sunday 9 May. Rail replacement buses will run. Kingston bus station closure Cromwell Road bus station in Kingston will be closed from Monday 17 to Sunday 23 May due to utility works being undertaken by Thames Water. Hospitality businesses – find out more about next COVID reopening milestone As we look forward to Monday 17 May, and hopefully the reopening of indoor hospitality, Richmond Council is hosting an event for local hospitality businesses to find out more about what that means for you and your business. -

2021-02 Spring Edition

TEAMtalk Spring 2021 A Different Form of Christmas It was a very different Christmas in RTM last December with bookable places only for the main services, no packed churches and a more limited chance to welcome those from the greater community of Richmond, who join us each year. Sadly, no Christingle services or Nativity plays for the children. All set against increasing levels of coronavirus. And yet, despite this sombre background the Christmas message was undimmed - God's great gift to humanity, the birth of the Christ Child, giving us hope and through his later sacrifice, the way to eternal life. It was a very different Christmas but it was still Christmas as the following pages show. Unable to hold our traditional Christingle service on Christmas Eve, we made up 50 Christingle make-at-home packs complete with orange, sweeties, ribbon, candle, a prayer and a link to enable a donation to be made to The Childrens’ Society. The bags were offered from the safety of the front garden of St Matthias’ vicarage in Cambrian Road, and families on their way to the Park stopped and were delighted to be offered a bag and a chance to celebrate at home. Revd Anne Crawford In this issue A Different form of Christmas: St Matthias 1-2 St John the Divine 2-4 St Mary Magdalene 4-5 Historic Vestments at SJD 6-7 Gill Gregorowski Walking with Christ - Lent 2020 8-9 Revd Anne Crawford An Adventure Like No Advent & Christmas 2020 at St Matthias Other 10 Advent 2020 certainly was a time of anticipation and waiting Fenella Warden heightened by the uncertainties of the pandemic with all the The Huguenots and the sadness, concerns and restrictions of present times. -

Housing & Regeneration

Official# PAYMENT PAYMENT SUPPLIER DIRECTORATE PAYEE ACTIVITY DATE AMOUNT NO Housing & Regeneration Business Systems U.K. 01/10/2020 3,391.64 Invoice Materials Directorate Ltd Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL Client Costs - Personal 01/10/2020 1,267.23 Invoice Directorate DATA Budget Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL 01/10/2020 1,559.97 Invoice DP prepaid cards Directorate DATA Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL 01/10/2020 875.83 Invoice Direct Payments to Clients Directorate DATA Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL 01/10/2020 2,489.69 Invoice Direct Payments to Clients Directorate DATA Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL 01/10/2020 506.31 Invoice Direct Payments to Clients Directorate DATA Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL 01/10/2020 4,185.09 Invoice Direct Payments to Clients Directorate DATA Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL 01/10/2020 728.14 Invoice DP prepaid cards Directorate DATA Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL Client Costs - Personal 01/10/2020 1,066.48 Invoice Directorate DATA Budget Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL Client Costs - Personal 01/10/2020 4,787.45 Invoice Directorate DATA Budget Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL Client Costs - Personal 01/10/2020 4,013.83 Invoice Directorate DATA Budget Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL Client Costs - Personal 01/10/2020 1,222.16 Invoice Directorate DATA Budget Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL Client Costs - Personal 01/10/2020 3,339.84 Invoice Directorate DATA Budget Adult Social Services REDACTED PERSONAL 01/10/2020 -

April-2020.Pdf

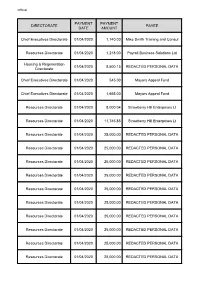

Official# PAYMENT PAYMENT DIRECTORATE PAYEE DATE AMOUNT Chief Executives Directorate 01/04/2020 1,740.00 Mike Smith Training and Consul Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 1,218.00 Payroll Business Solutions Ltd Housing & Regeneration 01/04/2020 8,500.15 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Directorate Chief Executives Directorate 01/04/2020 545.00 Mayors Appeal Fund Chief Executives Directorate 01/04/2020 1,665.00 Mayors Appeal Fund Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 8,000.04 Strawberry Hill Enterprises Lt Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 11,745.85 Strawberry Hill Enterprises Lt Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Official# Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA Resources Directorate 01/04/2020 25,000.00 REDACTED PERSONAL -

Local Funders Ebook

Local Funders Grants available in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames A guide to local grants that are open for applications throughout the year from charities, voluntary and community organisations. Ongoing Funding Sources Richmond Parish Lands Charity Purpose: - The relief of poverty in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. - The relief of sickness and distress in the Borough. - The provision and support of leisure and recreational facilities - The provision of educational facilities and support for people in Richmond wishing to undertake courses. - Any other charitable purpose for the benefit of the inhabitants of Richmond. Grants are available to both organisations and individuals and cover two strands of Main Grants Programme (Sharon le Ronde) and Education Grants (Amy Vogel). RPLC also manage two linked charities. The Bailey and Bates Trust Purpose: - The relief of poverty within SW14 postcode. Its charitable objects are advancing education (including social and physical training) of persons who are under the age of 25 years who are in need of financial assistance. Grants are available to individuals and organisations. Barnes Relief in Need Purpose: - The relief of poverty in the former borough of Barnes prior to 1965 (which roughly corresponds with SW14 postcode). Available for children and young people, the elderly and people with disabilities and to individuals and organisations. Contact 020 8948 5701 http://www.rplc.org.uk Hampton Fuel Allotments Charity Purpose: Hampton Fuel Allotment Charity supports families and individuals on low income with a grant to help with the costs of gas and electricity and essential household items It also provides grants to the voluntary sector to provide services and activities for people in need. -

Impact Report 2020

Impact Report 2020 Richmond Borough 4 Chair’s Remarks 5 Chief Executive’s Report Contents 6 Welcome to Richmond Borough Mind 7 We’re to help 8 Learning how to improve our wellbeing 10 Exploring new ways of being 12 Getting involved 13 Working with young people 14 Creating recovery plans 16 Engaging with others 18 Financial review 20 Thank you to our funders and fundraisers 21 Officeholders, trustees and management @richmondboroughmind @rb_mind @rb_mind RichmondBoroughMind Richmond Borough Mind 82 Heath Road T: 020 8948 7652 Twickenham E: [email protected] Charity No. 1146297 TW1 4BW W: www.rbmind.org Company No. 7954134 2 Richmond Borough Mind | Impact Report 2020 Richmond Borough Mind | Impact Report 2020 3 Chair’s remarks Chief Executive’s report As Chair of the Board of Richmond Borough Mind, it’s been my Firmly settled in our new offices at UK House, our services have privilege every year to tell you how proud my fellow directors and grown in 2019/20. The new space has enhanced our Counselling I are of the services which we provide to the people of Richmond service and has also helped to expand our Carers service. Our and its surrounds. The team and our many supporting volunteers Richmond Wellbeing Service continues to offer support to thousands provide vital help to a huge number of people out of all proportion to of residents experiencing common mental health problems. our small size. We were also very excited this year to open our two new Journey In the usual way this report tells of the services we provided in Recovery Hubs, offering out-of-hours support to those in Richmond the year to 31 March 2020 and I would like to say thank you to the and Kingston in immediate crisis.