The 1991 National Survey on Status of Rural Water Supply and Sanitation for Dphe/Unicef

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROFESSIONAL PROFILE of DR. AMARTYA KUMAR BHATTACHARYA

MULTISPECTRA CONSULTANTS AND MULTISPECTRA GLOBAL PROFESSIONAL PROFILE of DR. AMARTYA KUMAR BHATTACHARYA 1. Name : Prof. Dr. Er. Amartya Kumar ‘Jay’ Bhattacharya, Esq. BCE (Hons.) ( Jadavpur University ), MTech ( Civil ) ( Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur ), PhD ( Civil ) ( Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur ), Cert.MTERM ( Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok ), CEng(I), PEng(I), CEng, FASCE (USA), FICE (UK), FIE, FACCE(I), FISH, FIWRS, FIPHE, FIAH, FAE, FMA, MIGS, MIGS – Kolkata Chapter, MIGS – Chennai Chapter, MISTE, MAHI, MISCA, MIAHS, MISTAM, MNSFMFP, MIIBE, MICI, MIEES, MCITP, MISRS, MISRMTT, MAGGS, MCSI, MIAENG, MMBSI, MBMSM ( Founder, Owner and Chief Executive Officer of MultiSpectra Consultants, MultiSpectra Global, MultiSpectra Consultants Asia, MultiSpectra Technologies, MultiSpectra Aqua, MultiSpectra, Inc., MultiSpectra Bangladesh, MultiSpectra Tripura, MultiSpectra H2O and MultiSpectra SkyHawk. These ten Companies constitute the Diwan Bahadur Banga Chandra - Dr. Amartya Kumar Bhattacharya Group of Companies. ) ( Founder, Owner and Chief Executive Officer of MultiSpectra Academy, MultiSpectra iCreate Centre and MultiSpectra Global Business Accelerator, which are not-for-profit organisations. ) ( Founder and President of MultiSpectra Centre of Arid Regions Engineering, which is a not-for-profit research institution. ) ( Founder, Professor and Director of MultiSpectra Institute of Technology and MultiSpectra Business School. ) ( Announcing, MultiSpectra Global Singapore Pte. Ltd. ) 2. Nickname : Jay 3. Father’s -

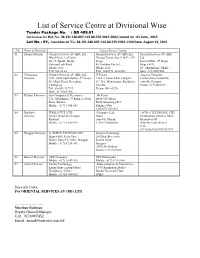

List of Service Centre at Divisional Wise Tender Package No

List of Service Centre at Divisional Wise Tender Package No. : GD 409.01 Invitation for Bid No: 38.151.180.007.115.00.376.2015-2062, Issued on : 01 June, 2015 Lot No : 01, Amendment No: 38.151.180.007.114.00.375.2015-1159 Date: August 13, 2015 S/L Name of Division List of Service Centre 01 Dhaka Division Oriental Services AV (BD) Ltd. Oriental Services AV (BD) Ltd. Oriental Services AV (BD) Mini Plaza ( 1st Floor), Navana Tower, Suit # 18/C ( 18th Ltd. Ga-93, Middle Badda Floor) Eastern Plus ( 4th Floor) Gulshan Link Road, 45, Gulshan Circle-1, Shop # 4/31, Dhaka-1212 Dhaka-1212 45, Shantinagar, Dhaka Tell: 986 26 38 Tell: 9884772, 8832260, Mob : 01730007454 02 Chittagong Oriental Services AV (BD) Ltd. IT Palace Success Computer Division 1401, Shah Abul Market (2nd Floor), TD-2-3, Sattar Khan Complex Chawmuhani,Nawakhali Sk. Mujib Road, Dewanhat, (3rd flr.), Monoharpur, Kandirpar. Atnn-Mr.Faruque Chittagong. Comilla. Mobile-01713600473 Tel : 88-031-727719, Phone- 081-61270 Mob : 01730007466 03 Khulna Division Sun Computer & Electronics Mr.Faisal 331, Jalil Market, 77 Khan-A-Sabur H#347(2nd floor) Road, Khulna. R#02,Sonadanga R/A Mobile : 01711-964-669 Khulna-9000. Cell-01711873315 04 Rajshahi PIXELS PVT. LTD. Computer Link ASTHA TECHSENSE LTD. Division Greater Road. Kerdirigonj. Nator 55,Gonokpara,Shaheb Bazar Rajshahi. Attn-Mr. Masud Rajshahi-6100 Mobile : 01711-346-991 Cell-01740886848 Attn-Mr. Firoz Ahmed Cell- 01716036453/01786737373 05 Rangpur Division G- FORCE TECHNOLOGY Seegate Technology Shop # 689, Press Club, 286,Shah Bari tower Market Jahaz Co. -

Productivity, Life History and Long Term Catch Projections for Hilsa Shad

1 Biology and Fisheries of Hilsa shad in Bay of Bengal 2 Mostafa A. R. Hossain1,*, Isha Das2, Lily Genevier3, Sugata Hazra2, Md. Munsur 3 Rahman4, Manuel Barange3,5, Jose A. Fernandes3,6 4 5 1. Department of Fish Biology & Genetics, Bangladesh Agricultural University, 6 Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh 7 2. School of Oceanographic Studies, Jadavpur University, India 8 3. Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Prospect Place, The Hoe, Plymouth, U.K. PL13 DH 9 4. Institute of Water and Flood Management, Bangladesh University of Engineering and 10 Technology, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh 11 5. Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy and Resources Division, Food and Agriculture 12 Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy 001536 13 6. AZTI, Herrera Kaia, Portualdea, z/g, Pasaia (Gipuzkoa), 20110, Spain 14 15 16 17 18 Running Title: Productivity, life history and catch of Hilsa 19 *Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. Email: [email protected] 20 Abstract 21 Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) or river shad is an anadromous fish species widely distributed in 22 the North Indian Ocean, mainly in the Bay of Bengal (BoB). Hilsa is the national fish of 23 Bangladesh and it contributes 10% of the total fish production of the country, with a market 24 value of $1.74 billion. Hilsa also holds a very important place in the economics of West 25 Bengal of India with 12.5% of the catch and also tops the marine capture in Myanmar. 26 During the last two decades Hilsa production from inland waters has been stable, whereas 27 marine yields in the BoB increased substantially. -

Tax Payer Communication Plan

GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH Ministry of Finance/Internal Resources Division National Board of Revenue (NBR) Taxpayer Communication Plan 2015-16 Taxpayer Communication Plan 2015-2016 under Taxpayer Communication Strategy, 2014-2019 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Taxpayer Communication Programmes ............................................................................................... 3 2.1. Taxpayers Training ........................................................................................................................ 3 2.2. Seminars and Workshop with taxpayers........................................................................................ 4 2.2.1 Seminars/workshops at National Level .................................................................................... 4 2.2.2 Seminars/workshops at Commissionerate Level ...................................................................... 6 2.2.3 Seminars/workshops at Division Level ..................................................................................... 7 3. Advertisement: .................................................................................................................................. 10 4. Road Show: ....................................................................................................................................... 11 5. Taxpayer Advocacy Visits .................................................................................................................. -

Gender Roles in the Jute Value Chain in Bangladesh: a Case Study on the Bangladesh Agricultural Value Chains (AVC) Project

Gender Roles in the Jute Value Chain in Bangladesh: A Case Study on the Bangladesh Agricultural Value Chains (AVC) project Deborah Rubin,1 Emily Myers2, Salma Akhter3, Berber Kramer2, Alan de Brauw2, and Mike Murphy2 November 26th, 2018 (Revised) 1 Cultural Practice, LLC 2 International Food Policy Research Institute 3 University of Dhaka 1 Contents Acknowledgements 4 Acronyms 5 Executive Summary 6 Background 7 Methodology 8 Context: Gender, Agriculture, Jute, and the Agricultural Value Chains (AVC) Project 10 Gender Relations in Bangladesh 10 Gender Relations in Agriculture 11 The Jute Value Chain in Bangladesh 12 The Bangladesh Agricultural Value Chain (AVC) Project 14 Findings: Activities at each nodes of the Jute Value Chain 16 Input Suppliers 16 Producers 17 Cultivation 17 Fertilizers 19 Post-Harvest and Homestead Processing 20 Jute Traders and Transporters 21 Trader Profile 25 Trader Profile 25 Manufacture of Jute Products 25 Findings: Participant Engagement with the Agricultural Value Chains (AVC) Project 26 Agricultural Training 26 Observations and Recommendations from Agriculture Officers 27 Findings: Empowerment and Respect 28 Empowerment and the pro-WEAI 28 Women’s Views on Respectable Women 28 Women’s Views on Respectable Men 29 Men’s View on Respectable Women 29 Men’s View on Respectable Men 30 Findings: Empowerment and Decision-making 30 Men’s Views on Empowered Women 30 Women’s Views on Empowered Women 32 2 Men’s Views on Empowered Men 32 Women’s Views on Empowered Men 33 Areas of Men’s and Women’s Decision-Making 33 Findings: Group Membership 34 Findings: Mobility 35 Findings: Education 36 Implication of Findings for USAID and the AVC project 36 Integrating women into a market systems approach 36 Supporting Group Membership. -

E-Tender Notice

GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ENGINEER HEALTH ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT (HED) MINISTRY OF HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE 105-106, MOTIJHEEL C/A, DHAKA-1000 Memo No HED/HPNSP/GOB/e-Tender- 578, 662, 712 & 722/2017-18/ 243, Dated : 08/10/2018 e-Tender Notice. e-Tender is invited in the National e-GP System Portal (http://www.eprocure.gov.bd) for the procurement of following works, details are given below: Last Date & Tender Sl Tender Package No Description of Work Time of Selling Closing date No. ID No Tender & Time Document Construction of Koilail 10 Bed Mother & 01 221302 WP-70/SDP- 05.11.2018 06.11.2018 4 –(GOB)-HED Child Welfare Center at Nawabgonj Upazila & & in Dhaka District 18.00 14.30 02 232296 WP-84/SDP- Construction of Kumirgari Biswaspara10 Bed 04.11.2018 05.11.2018 4 –(GOB)-HED Mother & Child Welfare Center at Sathia & & Upazila in Pabna District 17.00 15.15 03 232295 WP-5096/SDP- Construction of Kasinathpur 10 Bed Mother 04.11.2018 05.11.2018 4 –(GOB)-HED & Child Welfare Center at Sathia Upazila in & & Pabna District 17.00 15.30 04 WP-13445/SDP- Construction of Bhangardia10 Bed Mother & 232297 06.11.2018 07.11.2018 4 –(GOB)-HED Child Welfare Center at Nurullagonj Union & & under Bhanga Upazila in Faridpur District 17.00 15.00 This is an online Tender, where only e-Tender will be accepted in the National e-GP Portal and no offline/hard copies will be accepted. To submit e-Tender, registration in the National e-GP System Portal (http://www.eprocure.gov.bd) is required. -

The Role of Local Government Finance

Public Disclosure Authorized IMPROVING LOCAL GOVERNANCE AND SERVICE DELIVERY IN BANGLADESH: THE ROLE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized IMPROVING LOCAL GOVERNANCE AND SERVICE DELIVERY IN BANGLADESH: THE ROLE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE Preface [Preface by LGD Senior Secretary to be inserted here.] i IMPROVING LOCAL GOVERNANCE AND SERVICE DELIVERY IN BANGLADESH: THE ROLE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE Executive Summary Context and objective. Local government institutions at different levels (Zila, Upazila and Union) play an important—but sometimes overlooked—role in public service delivery and sustainable development in Bangladesh. While these LGIs do not play a leading role in delivering key public services—such as primary education or basic health services—local governments are nonetheless an important partner in ensuring effective and inclusive service delivery. Although there is a recognition that local government institutions are generally under-resourced to perform the functions assigned to them, relatively little is known about the exact size, composition and distribution of intergovernmental finances in Bangladesh. This report, as the first analysis of its kind, provides a “big picture” overview of local government revenues and expenditures for UPs, Upazila Parishads, Pourashavas, and City Corporations. It focuses on providing a basic quantitative overview of the expenditures, revenues and transfers of different types of LGIs. Rather than relying on sample analysis and case studies, the current document aims to represent as comprehensive and as accurate a view as possible of expenditures for all local government institutions in Bangladesh. As such, the analysis is based on data for all 4538 Union Parishads; financial data for all pourashavas for which complete and consistent financial reports were available (175 out of 329 pourashavas); financial data for all 11 City Corporations; and well as financial data (albeit incomplete) for all 492 Upazila Parishads. -

E-Tender Notice

GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ENGINEER HEALTH ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT (HED) MINISTRY OF HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE 105-106, MOTIJHEEL C/A, DHAKA-1000 www.hed.gov.bd /e-mail: [email protected] Memo No. HED/HPNSP/e-Tender- 310,711/2018/224 Dated: 20/09/2018 e-Tender Notice e-Tender is invited in the National e-GP System Portal (http://www.eprocure.gov.bd) for the procurement of following works, details are given below: Sl Tender Package No Description of Work Last Date & Time of Tender No. ID No Selling Tender Closing date & Document Time 1. Tender ID: WP- Upgradation, Repair & Renovation of 21.10.2018 22.10.2018 221299 4841/SDP- Kawkhali Upazila Health Complex UzHC 18:00 15:00 4(GOB)-HED from 31 to 50 Bed in Rangamati District. 2. Tender ID: WP- Construction of Tofurnnesa 10 Bed 21.10.2018 22.10.2018 221303 13461/SDP- Mother and Child Welfare Centre at 18:00 14:45 4(GOB)-HED Gondhorbbopur North union under Hazigonj Upazila in Chandpur District. This is an online Tender, where only e-Tender will be accepted in the National e-GP Portal and no offline/hard copies will be accepted. To submit e-Tender, registration in the National e-GP System Portal (http://www.eprocure.gov.bd) is required. The fees for downloading the e-Tender Documents from the National e-GP System Portal have to be deposited online through any registered Bank’s branches. Further information and guidelines are available in the National e-GP System Portal and from e-GP help desk ([email protected]). -

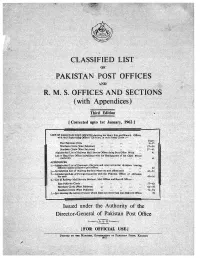

Pak Pos and RMS Offices 3Rd Ed 1962

Instructions for Sorting Clerks and Sorters ARTICLES ADDRl!SSBD TO TWO PosT-TOWNS.-If the address Dead Letter Offices receiving articles of the description re 01(an article contains the names of two post-town, the article ferred in this clause shall be guided by these instructions so far should, as a general rule, be forwarded to whichever of the two as the circumstances of each case admit of their application. towns is named last unless the last post-town- Officers employed in Dead Letter Offices are selected for their special fitness for the work and are expected to exercise intelli ( a) is obviously meant to indicate the district, in which gence and discretion in the disposal of articles received by case the article should be . forwar ~ ed ~ · :, the first them. named post-town, e. g.- A. K. Malik, Nowshera, Pes!iaivar. 3. ARTICLES ADDRESSED TO A TERRITORIAL DIVISION WITH (b) is intended merely as a guide to the locality, in which OUT THE ADDITION OF A PosT-TOWN.-If an article is addressed case the article should be forwarded to the first to one of the provinces, districts, or other territorial divisions named post-town, e. g.- mentioned in Appendix I and the address does not contain the name of any post-town, it should be forwarded to the post-town A. U. Khan, Khanpur, Bahawalpur. mentioned opposite, with the exception of articles addressed to (c) Case in which the first-named post-town forms a a military command which are to be sent to its headquarters. component part of the addressee's designation come under the general rule, e. -

Appendix F: Name of Region, District and Upazila/Thana

List of District and Upazila/Thana Office (01) Dhaka Division 1 Norshingdi Sadar Upozila Monorhordi Upozila Shibpur Upozila Palash Upozila Belab Upozila Raipura Upozila 2 Narayangonj Sadar Upozila Bandor Upozila Sonargaon Upozila Arai Hazar Upozila Rupgonj Upozila 3 Munshigonj Sadar Upozila Tungibari Upozila Louhagonj Upozila Sree Nagar Upozila Sirajdi Khan Upozila Gazaria Upozila 4 Gazipur Sadar Upozila Tongi Upozila kaligonj Upozila Kaliakoir Upozila Kapashia Upozila Sreepur Upozila 5 Manikgonj Sadar Upozila Singair Upozila Daulatpur Upozila Horirampur Upozila Gheor Upozila Shibaloy Upozila Saturia Upozila 6 Dhaka Kotwali Thana Mohammadpur Thana Lalbagh Thana Sutrapur Thana Motijgil Thana Demra Thana Sabujbagh Thana Mirpur Thana Gulshan Thana Uttara Thana Pallabi Thana Cantonment Thana Dhanmondi Thana Tejgaon Thana Ramna Thana Keranigonj Upozila Dohar Upozila Nawabgonj Upozila Savar Upozila Dhamrai Upozila (2) Faridpur Region 1 Faridpur Sadar Upozila Boalmari Upozila Sadarpur Upozila Char Bhadrashon Upozila Bhanga Upozila Nagarkanda Upozila Madhukhali Upozila Alphadanga Upozila SalThanaa Upozila 2 Rajbari Sadar Upozila Pangsha Upozila Goalondo Upozila Kalukhali Upozila Baliakandi Upozila 3 Gopalgonj Sadar Upozila kashiani Upozila Tongipara Upozila Muksudpur Upozila Kotalipara Upozila 4 Madaripur Sadar Upozila Kalkini Upozila Rajoir Upozila Shibchar Upozila 5 Sariyatpur Sadar Upozila Damudda Upozila Noria Upozila Jagira Upozila Vedorgonj Upozila Goshair Hat Upozila (3) Barishal Regeon Sadar Upozila Amtoli Upozila Betagi Upozila 1 Borguna -

Shock-Responsive Social Protection in Bangladesh Literature Review

Shock-Responsive Social Protection in Bangladesh Literature Review Madhumitha Hebbar and Shamir Shehab May 2020 Shock-Responsive Social Protection in Bangladesh: Literature Review About Maintains Maintains aims to save lives and reduce suffering for people in developing countries affected by shocks such as pandemics, floods, droughts, and population displacement. This five-year programme, spanning 2018-2023, is building a strong evidence base on how health, education, nutrition, and social protection systems can respond more quickly, reliably, and effectively to changing needs during and after shocks, whilst also maintaining existing services. With evidence gathered from six focal countries—Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kenya, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, and Uganda—Maintains is working to inform policy and practice globally. It also provides technical assistance to support practical implementation. This output has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. Maintains is implemented through a consortium led by Oxford Policy Management www.opml.co.uk. For more information about the programme, visit the Maintains webpage and for any questions or comments, please get in touch with [email protected]. © Maintains i Shock-Responsive Social Protection in Bangladesh: Literature Review Acknowledgments Thanks to the range of people who provided feedback on, and inputs into, this review, including Anowarul Haq, Rodolfo Beazley, Arafat Alam, Josh Chipman, and Lucy -

Education System and Its Importance in the Context of Bangladesh Education System

Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal – Vol.4, No.15 Publication Date: Aug. 25, 2017 DoI:10.14738/assrj.415.3499. Al Noor, M. (2017). Education System and Its Importance in the Context of Bangladesh Education System. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 4(15) 36-45. Education System and Its Importance in the Context of Bangladesh Education System Dr. Masud Al Noor Dept.of Apparel Manufacturing Management & Technology Shanto-Mariam University of Creative Technology ABSTRACT Education is the back bone of the nation. Without proper education it cannot be possible to make a wise nation. Bangladesh education system is not competitive in terms of compare with international level. Lack of unified curriculum and skilled teacher is the main factor to develop education sector and political illness is another factor to improve those system. It is time to identify the problems and find out the remedy. With a strong education system a highly qualified generation may emerge to lead Bangladesh in realizing the dreams and goals of the nation. The paper presents a significant analysis of education system of Bangladesh. Key Words: Education System, University Grants Commission, Higher Education, Quality Assurance INTRODUCTION The education system in Bangladesh encompasses both formal and non-formal education. Both types are available in a religious variant. Non-formal education encompasses organized, structured learning that takes place outside of the school environment. EXamples of this include programmes aimed at tackling illiteracy, work related or talent development programmes, such as company training and lifelong learning programmes, but also training programmes for those who have left school without a qualification.