Productivity, Life History and Long Term Catch Projections for Hilsa Shad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status of Fish and Shellfish Diversity and Their Decline Factors in the Rupsa River of Khulna in Bangladesh Sazzad Arefin1, Mrityunjoy Kunda1, Md

Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science 3(3): 232-239 (2018) https://doi.org/10.26832/24566632.2018.030304 This content is available online at AESA Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science Journal homepage: www.aesacademy.org e-ISSN: 2456-6632 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Status of fish and shellfish diversity and their decline factors in the Rupsa River of Khulna in Bangladesh Sazzad Arefin1, Mrityunjoy Kunda1, Md. Jahidul Islam1, Debasish Pandit1* and Ahnaf Tausif Ul Haque2 1Department of Aquatic Resource Management, Sylhet Agricultural University, Sylhet-3100, BANGLADESH 2Department of Environmental Science and Management, North South University, Dhaka, BANGLADESH *Corresponding author’s E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE HISTORY ABSTRACT Received: 13 August 2018 The study was aimed to find out the present status and causes of fish and shellfish diversity Revised received: 21 August 2018 reduction in the Rupsa River of Bangladesh. Studies were conducted for a period of 6 months Accepted: 26 August 2018 from July to December 2016. Focus group discussions (FGD), questionnaire interviews (QI) and key informant interviews (KII) were done to collect appropriate data from the local fishers and resource persons. A total of 62 species of fish and shellfish from 23 families were found in the river and 9 species disappeared in last 10 years. The species availability status was Keywords remarked in three categories and obtained as 14 species were commonly available, 28 species were moderately available and 20 species were rarely available. The highest percentage of Aquaculture Biodiversity fishes was catfishes (24.19%). There was a gradual reduction in the species diversity from Fishes and shellfishes previous 71 species to present 62 species with 12.68% declined by last 10 years. -

The Conservation Action Plan the Ganges River Dolphin

THE CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN FOR THE GANGES RIVER DOLPHIN 2010-2020 National Ganga River Basin Authority Ministry of Environment & Forests Government of India Prepared by R. K. Sinha, S. Behera and B. C. Choudhary 2 MINISTER’S FOREWORD I am pleased to introduce the Conservation Action Plan for the Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica gangetica) in the Ganga river basin. The Gangetic Dolphin is one of the last three surviving river dolphin species and we have declared it India's National Aquatic Animal. Its conservation is crucial to the welfare of the Ganga river ecosystem. Just as the Tiger represents the health of the forest and the Snow Leopard represents the health of the mountainous regions, the presence of the Dolphin in a river system signals its good health and biodiversity. This Plan has several important features that will ensure the existence of healthy populations of the Gangetic dolphin in the Ganga river system. First, this action plan proposes a set of detailed surveys to assess the population of the dolphin and the threats it faces. Second, immediate actions for dolphin conservation, such as the creation of protected areas and the restoration of degraded ecosystems, are detailed. Third, community involvement and the mitigation of human-dolphin conflict are proposed as methods that will ensure the long-term survival of the dolphin in the rivers of India. This Action Plan will aid in their conservation and reduce the threats that the Ganges river dolphin faces today. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. R. K. Sinha , Dr. S. K. Behera and Dr. -

Cachar District

[TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE GAZETTE OF INDIA, EXTRAORDINARY, PART II SECTION 3, SUB SECTION (II)] GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF FINANCE (DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE) Notification No. 45/2010 - CUSTOMS (N.T.) 4th JUNE, 2010. 14 JYESTHA, 1932 (SAKA) S.O. 1322 (E). - In exercise of the powers conferred by clauses (b) and (c) of section 7 of the Customs Act, 1962 (52 of 1962), the Central Government hereby makes the following further amendment(s) in the notification of the Government of India in the Ministry of Finance (Department of Revenue), No. 63/94-Customs (NT) ,dated the 21st November, 1994, namely:- In the said notification, for the Table, the following Table shall be substituted, namely;- TABLE S. Land Land Customs Routes No. Frontiers Stations (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. Afghanistan (1) Amritsar Ferozepur-Amritsar Railway Line (via Railway Station Pakistan) (2) Delhi Railway Ferozepur-Delhi Railway Line. Station 2. Bangladesh CALCUTTA AND HOWRAH AREA (1) Chitpur (a) The Sealdah-Poradah Railway Line Railway Station passing through Gede Railway Station and Dhaniaghat and the Calcutta-Khulna Railway line River Station. passing through Bongaon (b) The Sealdah-Lalgola Railway line (c) River routes from Calcutta to Bangladesh via Beharikhal. (2) Jagannathghat The river routes from Calcutta to Steamer Station Bangladesh via Beharikhal. and Rajaghat (3) T.T. Shed The river routes from Calcutta to (Kidderpore) Bangladesh via Beharikhal. CACHAR DISTRICT (4) Karimganj (a) Kusiyara river Ferry Station (b) Longai river (c) Surma river (5) Karimganj (a) Kusiyara river Steamerghat (b) Surma river (c) Longai river (6) Mahisasan Railway line from Karimganj to Latu Railway Station Railway Station (7) Silchar R.M.S. -

PROFESSIONAL PROFILE of DR. AMARTYA KUMAR BHATTACHARYA

MULTISPECTRA CONSULTANTS AND MULTISPECTRA GLOBAL PROFESSIONAL PROFILE of DR. AMARTYA KUMAR BHATTACHARYA 1. Name : Prof. Dr. Er. Amartya Kumar ‘Jay’ Bhattacharya, Esq. BCE (Hons.) ( Jadavpur University ), MTech ( Civil ) ( Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur ), PhD ( Civil ) ( Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur ), Cert.MTERM ( Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok ), CEng(I), PEng(I), CEng, FASCE (USA), FICE (UK), FIE, FACCE(I), FISH, FIWRS, FIPHE, FIAH, FAE, FMA, MIGS, MIGS – Kolkata Chapter, MIGS – Chennai Chapter, MISTE, MAHI, MISCA, MIAHS, MISTAM, MNSFMFP, MIIBE, MICI, MIEES, MCITP, MISRS, MISRMTT, MAGGS, MCSI, MIAENG, MMBSI, MBMSM ( Founder, Owner and Chief Executive Officer of MultiSpectra Consultants, MultiSpectra Global, MultiSpectra Consultants Asia, MultiSpectra Technologies, MultiSpectra Aqua, MultiSpectra, Inc., MultiSpectra Bangladesh, MultiSpectra Tripura, MultiSpectra H2O and MultiSpectra SkyHawk. These ten Companies constitute the Diwan Bahadur Banga Chandra - Dr. Amartya Kumar Bhattacharya Group of Companies. ) ( Founder, Owner and Chief Executive Officer of MultiSpectra Academy, MultiSpectra iCreate Centre and MultiSpectra Global Business Accelerator, which are not-for-profit organisations. ) ( Founder and President of MultiSpectra Centre of Arid Regions Engineering, which is a not-for-profit research institution. ) ( Founder, Professor and Director of MultiSpectra Institute of Technology and MultiSpectra Business School. ) ( Announcing, MultiSpectra Global Singapore Pte. Ltd. ) 2. Nickname : Jay 3. Father’s -

Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita (2013) Wheels of Change?: Impact of Railways on Colonial North Indian Society, 1855-1920. Phd Thesis. SO

Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita (2013) Wheels of change?: impact of railways on colonial north Indian society, 1855‐1920. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/17363 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Wheels of Change? Impact of railways on colonial north Indian society, 1855-1920. Aparajita Mukhopadhyay Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2013 Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1 | P a g e Declaration for Ph.D. Thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work that I present for examination. -

Impact Assessment Due to Rural Electrification in Hill Tract of Bangladesh for Sustainable Development

Int. J. Environ. Sci. Tech., 3 (4): 391-402, 2006 ISSN:Md. J. 1735-1472B. Alam, et al. Impact assessment due... © Autumn 2006, IRSEN, CEERS, IAU Impact assessment due to rural electrification in hill tract of Bangladesh for sustainable development *1Dr. Md. J. B. Alam, 2M. R. Islam, 1R. Sharmin, 3Dr. M. Iqbal, 1M. S. H. Chowduray and 1G. M. Munna 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh 2Department of Chemistry, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh 3 Department of Industrial and Production Engineering, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh Received 25 March 2006; revised 15 August 2006; accepted 1 September 2006; available online 1 October 2006 ABSTRACT: Environmental impact assessment (EIA) of any project is essential for understanding the sustainability of the project. For sustainable development of hill tracts, electricity is inseparable. Like other parts of Bangladesh hill tracts districts felt increasing demand of electricity. In this paper an attempt has been taken to present the existing environmental condition and analysis the future environmental condition after implementation of project. Electrification will extend the length of the active day. Electrification will improve security (people’s perception of safety and security) at the region. The elements of the project identified as components for analysis are chosen based on DOE’s guideline. The study showed that 87% people say that they feel safer at night since being electrified. Impacts are classified on the basis of EPA’s scaling and DOE, university’s teachers, NGOs expert’s opinions. Value more than 10 is classified significantly affected element of the project. -

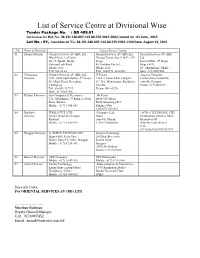

List of Service Centre at Divisional Wise Tender Package No

List of Service Centre at Divisional Wise Tender Package No. : GD 409.01 Invitation for Bid No: 38.151.180.007.115.00.376.2015-2062, Issued on : 01 June, 2015 Lot No : 01, Amendment No: 38.151.180.007.114.00.375.2015-1159 Date: August 13, 2015 S/L Name of Division List of Service Centre 01 Dhaka Division Oriental Services AV (BD) Ltd. Oriental Services AV (BD) Ltd. Oriental Services AV (BD) Mini Plaza ( 1st Floor), Navana Tower, Suit # 18/C ( 18th Ltd. Ga-93, Middle Badda Floor) Eastern Plus ( 4th Floor) Gulshan Link Road, 45, Gulshan Circle-1, Shop # 4/31, Dhaka-1212 Dhaka-1212 45, Shantinagar, Dhaka Tell: 986 26 38 Tell: 9884772, 8832260, Mob : 01730007454 02 Chittagong Oriental Services AV (BD) Ltd. IT Palace Success Computer Division 1401, Shah Abul Market (2nd Floor), TD-2-3, Sattar Khan Complex Chawmuhani,Nawakhali Sk. Mujib Road, Dewanhat, (3rd flr.), Monoharpur, Kandirpar. Atnn-Mr.Faruque Chittagong. Comilla. Mobile-01713600473 Tel : 88-031-727719, Phone- 081-61270 Mob : 01730007466 03 Khulna Division Sun Computer & Electronics Mr.Faisal 331, Jalil Market, 77 Khan-A-Sabur H#347(2nd floor) Road, Khulna. R#02,Sonadanga R/A Mobile : 01711-964-669 Khulna-9000. Cell-01711873315 04 Rajshahi PIXELS PVT. LTD. Computer Link ASTHA TECHSENSE LTD. Division Greater Road. Kerdirigonj. Nator 55,Gonokpara,Shaheb Bazar Rajshahi. Attn-Mr. Masud Rajshahi-6100 Mobile : 01711-346-991 Cell-01740886848 Attn-Mr. Firoz Ahmed Cell- 01716036453/01786737373 05 Rangpur Division G- FORCE TECHNOLOGY Seegate Technology Shop # 689, Press Club, 286,Shah Bari tower Market Jahaz Co. -

Protection of Endangered Ganges River Dolphin in Brahmaputra River, Assam, India

PROTECTION OF ENDANGERED GANGES RIVER DOLPHIN IN BRAHMAPUTRA RIVER, ASSAM, INDIA Final Technical Report to Sir Peter Scott Fund, IUCN Report submitted by - Abdul Wakid, Ph. D. Programme Leader Gangetic Dolphin Research & Conservation Programme, Aaranyak Survey, Beltola, Guwahati-781028 Assam, India Gill Braulik Sea Mammal Research Unit University of St. Andrews St. Andrews, Fife KY16 8LB, UK Page | 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We are expressing our sincere thanks to Sir Peter Scott Fund of IUCN for funding this project. We are thankful to the Department of Environment & Forest (wildlife) and the management authority of Kaziranga National Park, Government of Assam for the permission to carry out the study, especially within Kaziranga National Park. Without the tremendous help of Sanjay Das, Dhruba Chetry, Abdul Mazid and Lalan Sanjib Baruah, the Project would not have reached its current status and we are therefore grateful to all these team members for their field assistance. The logistic support provided by the DFO of Tinsukia Wildlife Division and the Mongoldoi Wildlife Division are highly acknowledged. Special thanks to Inspector General of Police (special branch) of Assam Police Department for organizing the security of the survey team in all districts in the Brahamputra Valley. In particular Colonel Sanib, Captain Amrit, Captain Bikash of the Indian Army for the security arrangement in Assam-Arunachal Pradesh border and Assistant Commandant Vijay Singh of the Border Security Force for security help in the India-Bangladesh border area. We also express our sincere thanks to the Director of Inland Water Transport, Alfresco River Cruise, Mr. Kono Phukan, Mr. Bhuban Pegu and Mr. -

Quality Changes in Formalin Treated Rohu Fish (Labeo Rohita, Hamilton) During Ice Storage Condition

Asian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2(4): 158-163, 2010 ISSN: 2041-3890 © Maxwell Scientific Organization, 2010 Submitted Date: May 31, 2010 Accepted Date: June 26, 2010 Published Date: October 09, 2010 Quality Changes in Formalin Treated Rohu Fish (Labeo rohita, Hamilton) During Ice Storage Condition T. Yeasmin, M.S. Reza, F.H. Shikha, M.N.A. Khan and M. Kamal Department of Fisheries Technology, Faculty of Fisheries, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh Abstract: The study was conducted to evaluate the influence of formalin on the quality changes in rohu fish (Labeo rohita, Hamilton) during ice storage condition. There are complaints from the consumers that the fish traders in Bangladesh use formalin in fish imported from neighboring countries to increase the shelf life. On the basis of organoleptic characteristics, the formalin treated fishes were found in acceptable condition for 28 to 32 days in ice as compared to the control fish, which showed shelf life of 20 to 23 days. Bacterial load in formalin treated fish was below detection level even after 16 days of ice storage whereas bacterial load was significantly higher in fresh rohu stored in ice and at the end of 24 days of ice storage. NPN content was increased gradually in fresh rohu with the increased storage period in ice. On the other hand, NPN content of formalin treated rohu decreased gradually during the same period of storage. Protein solubility in formalin treated fish decreased significantly to 25% from initial of 58% during 24 days of ice storage as compared to 40% from initial of 86.70% for control fish during the same ice storage period. -

Record of Skeletal System and Pin Bones in Table Size Hilsa Tenualosa Ilisha (Hamilton, 1822)

World Journal of Fish and Marine Sciences 6 (3): 241-244, 2014 ISSN 2078-4589 © IDOSI Publications, 2014 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wjfms.2014.06.03.83178 Record of Skeletal System and Pin Bones in Table Size Hilsa Tenualosa ilisha (Hamilton, 1822) 1B.B. Sahu, 21M.K. Pati, N.K. Barik, 1P. Routray, 11S. Ferosekhan, D.K. Senapati and 1P. Jayasankar 1Central Institute of Freshwater Aquaculture, Kausalyaganga, Bhubaneswar-751002, India 2Vidyasagar University, Midnapore-721102, West Bengal, India Abstract: The number, shape, sizes of intermuscular bones in table size (around 900g) hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) has been studied after microwave cooking and dissection. Hilsa intermuscular bones have varied shape and size. These pin bones are slender and soft which of two types, Y Pin bones and straight pin bones. Total number of pin bones in hilsa was found to be 138 nos. Y pin bones in each side was found to be 37 and straight bones in each side was 32. Both types of pin bones were slender springy and their distal end were not brushy. Branched pin bones were located on the dorsal broad muscle and unbranched pin bones were found in the posterior tail region. Key words: Hilsa Intermuscular Bones Pin Bones Tenualosa ilisha Y Pin Bones INTRODUCTION up to back bone [3]. Branched pin bones extend horizontally from the neutral or hemal spines into the The Indian shad hilsa, Tenualosa ilisha white muscle tissue. Abdominal portion of lower bundles (Hamilton, 1822) is one of the most important tropical are devoid of pin bones. Due to higher pin bones filleting fishes in the Indo-Pacific region and has occupied a top of hilsa is difficult. -

Seed Production of Indian Major and Minor Carps in Fiberglass Reinforced

International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 2016; 4(4): 31-34 ISSN: 2347-5129 (ICV-Poland) Impact Value: 5.62 (GIF) Impact Factor: 0.352 Seed production of Indian major and minor carps in IJFAS 2016; 4(4): 31-34 © 2016 IJFAS fiberglass reinforced plastic (FRP) hatchery at Bali, a www.fisheriesjournal.com remote Island of Indian Sunderban Received: 07-05-2016 Accepted: 08-06-2016 PP Chakrabarti PP Chakrabarti, BC Mohapatra, A Ghosh, SC Mandal, D Majhi and ICAR-Central Institute of P Jayasankar Freshwater Aquaculture, Field Station Kalyani, West Bengal, India. Abstract One unit of FRP carp hatchery with one breeding pool, one hatching pool, one egg/ spawn collection tank BC Mohapatra and one plastic made overhead tank of capacity 2000 litre was installed and operated at Bali Island, ICAR-Central Institute of Sunderban, West Bengal during 2014-15. During July - August, 2015 for the first time the successful Freshwater Aquaculture, induced breeding of Indian major carps (rohu, Labeo rohita and catla, Catla catla) and Indian minor carp Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. (bata, Labeo bata) was conducted in the established hatchery and 18.5 lakhs spawn was harvested. In this experiment spawning fecundity of rohu was found to be 0.88-1.0 lakh, catla 0.95 lakh and bata 1.1-1.3 A Ghosh lakh egg/kg bodyweight of female fish. Time for completion of egg hatching was found more or less ICAR-Central Institute of similar in rohu 920-970 minutes, catla 965 minutes and bata 940-990 minutes. Percentage of spawn Freshwater Aquaculture, Field survival from egg release was calculated to be 85.5-92.5% in rohu, 84.5% in catla and 86.5-90% in bata. -

Heavy Metals Contamination of River Water and Sediments in the Mangrove Forest Ecosystems in Bangladesh: a Consequence of Oil Spill Incident

Heavy Metals Contamination of River Water and Sediments in The Mangrove Forest Ecosystems in Bangladesh: A Consequence of Oil Spill Incident Tasrina Rabia Choudhury ( [email protected] ) Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6717-2550 Thamina Acter East-West University Nizam Uddin Daffodil International University Masud Kamal Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission A.M. Sarwaruddin Chowdhury Dhaka University M. Saur Rahman Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission Research Article Keywords: Sundarbans, lead, chromium, water quality index, metal pollution index, enrichment factor, geo-accumulation Posted Date: February 15th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-164143/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/24 Abstract Oil spillage is one of the common pollution events of global water-soil ecosystems. A comprehensive investigation on heavy metals pollution of surface water and sediments was conducted after oil spill incident in Sela River and its tributaries of the Sundarbans mangrove forest ecosystems, Bangladesh. Water and sediment samples were collected from the preselected sampling points in Sela River, and the elemental (Pb, Cd, Cr, Co, Cu, Ni, Fe, As, Hg, Mn, Zn, Ca, Mg, Na, and K) analysis was done using atomic absorption spectrometer (AAS). This study revealed that the descending order for the average concentration of the studied elements were found to be Mg > Co > Na > Ni > K > Ca > Pb > Fe > Mn > Cr > Cd > Zn > Cu respectively, while As and Hg in water samples were found to be below detection limit (BDL). However, some of the toxic elements in the Sela River water samples were exceeded the permissible limit set by the World Health Organization (WHO) with a descending order of Co > Cd > Pb > Ni respectively.