Boumediene V. Bush and Extraterritorial Habeas Corpus in Wartime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the PDF File

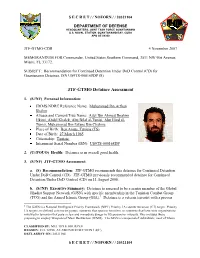

S E C R E T / / NOFORN / / 20321104 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE HEADQUARTERS, JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO U.S. NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA APO AE 09360 JTF-GTMO-CDR 4 November 2007 MEMORANDUM FOR Commander, United States Southern Command, 3511 NW 9lst Avenue, Miami, FL 33172. SUBJECT: Recommendation for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) for Guantanamo Detainee, ISN US9TS-000168DP (S) JTF-GTMO Detainee Assessment 1. (S//NF) Personal Information: JDIMS/NDRC Reference Name: Muhammad Ibn Arfhan Shahin Aliases and Current/True Name: Adel Bin Ahmed Ibrahim Hkimi, Abdel Khalek, Abu Bilal al-Tunisi, Abu Hind al- Tunisi, Muhammad Bin Erfane Bin Chahine Place of Birth: Ben Arous, Tunisia (TS) Date of Birth: 27 March 1965 Citizenship: Tunisia Internment Serial Number (ISN): US9TS-000168DP 2. (U//FOUO) Health: Detainee is in overall good health. 3. (S//NF) JTF-GTMO Assessment: a. (S) Recommendation: JTF-GTMO recommends this detainee for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD). JTF-GTMO previously recommended detainee for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) on 11 August 2006. b. (S//NF) Executive Summary: Detainee is assessed to be a senior member of the Global Jihadist Support Network (GJSN) with specific membership in the Tunisian Combat Group (TCG) and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA).1 Detainee is a veteran terrorist with a proven 1 The GJSN is a National Intelligence Priority Framework (NIPF) Priority 1A counter terrorism (CT) target. Priority 1A targets are defined as terrorist groups, countries that sponsor terrorism, or countries that have state organizations involved in terrorism that pose a clear and immediate danger to US persons or interests. -

\\Crewserver05\Data\Research & Investigations\Most Ethical Public

Stephen Abraham Exhibits EXHIBIT 1 Unlikely Adversary Arises to Criticize Detainee Hearings - New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/23/us/23gitmo.html?pagewanted=print July 23, 2007 Unlikely Adversary Arises to Criticize Detainee Hearings By WILLIAM GLABERSON NEWPORT BEACH, Calif. — Stephen E. Abraham’s assignment to the Pentagon unit that runs the hearings at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, seemed a perfect fit. A lawyer in civilian life, he had been decorated for counterespionage and counterterrorism work during 22 years as a reserve Army intelligence officer in which he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. His posting, just as the Guantánamo hearings were accelerating in 2004, gave him a close-up view of the government’s detention policies. It also turned him into one of the Bush administration’s most unlikely adversaries. In June, Colonel Abraham became the first military insider to criticize publicly the Guantánamo hearings, which determine whether detainees should be held indefinitely as enemy combatants. Just days after detainees’ lawyers submitted an affidavit containing his criticisms, the United States Supreme Court reversed itself and agreed to hear an appeal arguing that the hearings are unjust and that detainees have a right to contest their detentions in federal court. Some lawyers say Colonel Abraham’s account — of a hearing procedure that he described as deeply flawed and largely a tool for commanders to rubber-stamp decisions they had already made — may have played an important role in the justices’ highly unusual reversal. That decision once again brought the administration face to face with the vexing legal, political and diplomatic questions about the fate of Guantánamo and the roughly 360 men still held there. -

The Jose Padilla Story

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 48 Issue 1 Criminal Defense in the Age of Article 4 Terrorism January 2004 The Jose Padilla Story Donna R. Newman New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Donna R. Newman, The Jose Padilla Story, 48 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2003-2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. 18178_nlr_48-1-2 Sheet No. 23 Side A 04/27/2004 12:08:32 \\server05\productn\N\NLR\48-1-2\NLR211.txt unknown Seq: 1 16-APR-04 9:14 THE JOSE PADILLA STORY DONNA R. NEWMAN* The editors of the New York Law School Law Review have com- piled the following article primarily from briefs submitted to the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in connection with the federal government’s detention of Jose Padilla. The controver- sies connected with this case are still not resolved and new argu- ments continue to be developed as the case is briefed and presented to the Supreme Court.1 * * * “At a time like this, when emotions are understandably high, it is difficult to adopt a dispassionate attitude toward a case of this nature. -

In the United States District Court for the Dist~Ct of Columbia

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DIST~CT OF COLUMBIA BOUDELLAAL HAJJ, et al. Petitioners, Civil Action No. 04-CV-1166(RJL) GEORGEW. BUSH, Presidentof the UnitedStates, et al., Respondents. DECLARATIONOF JAMES R, CRISF1ELD JR. Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746, I, CommanderJames R. Crisfield Jr., Judge Advocate General’s Corps, United States Navy, hereby state that to the best of myknowledge, information and belief, the followingis tree, accurate and correct: 1. I am the Legal Advisor to the CombatantStatus ReviewTribunals. In that capacity I amthe principal legal advisor to the Director, CombatantStatus ReviewTribunals, and provide advice to Tribunals on legal, evidentiary, procedural, and other matters. I also reviewthe record of proceedingsin each Tribunal for legal sufficiency in accordancewith standards prescribed in the CombatantStatus ReviewTribunal establishment order and implementingdirective. 2. I hereby certify that the documentsattached hereto constitute a tree and accurate copy of the portions of the record of proceedings before the CombatantStatus ReviewTribunal related to petitioner BoudellaAI Hajj that are suitable for public release. Theportions of the record that are classified or consideredtaw enforcementsensitive are not attached hereto. I have redacted information that wouldpersonally identify other detainees and the family membersof detainees, as well as certain U.S. Governmentpersonnel in order to protect the personal security of those 5069 individuals. I have also redacted internee serial numbersbecause certain -

Enemy Combatants, the Courts, and the Constitution

Oklahoma Law Review Volume 56 Number 3 1-1-2003 Enemy Combatants, the Courts, and the Constitution Roberto Iraola Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr Part of the Criminal Procedure Commons, International Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Roberto Iraola, Enemy Combatants, the Courts, and the Constitution, 56 OKLA. L. REV. 565 (2003), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr/vol56/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oklahoma Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 56 FALL 2003 NUMBER 3 ENEMY COMBATANTS, THE COURTS, AND THE CONSTITUTION ROBERTO IRAOLA* L Introduction Three days after the September 11 attacks, when al Qaeda terrorists hijacked and crashed four commercial jetliners into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and the Pennsylvania countryside, killing over 3100 people,' Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the use of military force against those responsible.2 President George W. Bush responded by sending troops to Afghanistan to fight al Qaeda and its supporter, the Taliban regime.' During the military operation that ensued, thousands of prisoners were captured by allied and American forces.4 Many of those captured are * Senior Advisor to the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Law Enforcement and Security, Department of the Interior. J.D., 1983, Catholic University Law School. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. -

Does International Humanitarian Law Recognized This Concept? (Case Study: Armed Conflict Between United States, Al Qaeda and the Taliban)

Volume 7 No. 2, Agustus 2019 E-ISSN 2477-815X, P-ISSN 2303-3827 Nationally Accredited Journal, Decree No. 30/E/KPT/2018 open access at : http://jurnalius.ac.id/ojs/index.php/jurnalIUS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License THE CONCEPT OF ENEMY COMBATANT BY UNITED STATES: DOES INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW RECOGNIZED THIS CONCEPT? (CASE STUDY: ARMED CONFLICT BETWEEN UNITED STATES, AL QAEDA AND THE TALIBAN) Adhitya Nini Rizki Apriliana Master of Law, Universitas Airlangga email : [email protected] Lina Hastuti Universitas Airlangga email : [email protected] Abstract International humanitarian law recognized the classification of population during the war, namely: combatant; hors de combat; non-combatant; and civilians. Civilians is the parties who should be protected from enemy attacks and conversely this classification should not be attacked under any circumstances. In the other side of these classifications, the United States arrested around 200 Afghan children and teenagers on charges of being enemy combatant and detained them at the Detention Facility in Parwan. The act taken by the United States is not recognized in international humanitarian law since terms enemy combatant is not suitable with any other terms in international humanitarian law. The United States arrested children who did not took up arms and were not involved in the war but ‘allegedly’ involved with terrorist networks and were considered to treated state security. Phrase ‘allegedly’ refers to subjectivity and hard to describe. This research will discuss how international humanitarian law deal with the United States new terms namely enemy combatant. -

Extraordinary Rendition« Flights, Torture and Accountability – a European Approach Edited By: European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights E.V

WITH A PREFACE BY MANFRED NOWAK (UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON TORTURE) 1 SECOND EDITION 2 3 CIA- »EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION« FLIGHTS, TORTURE AND ACCOUNTABILITY – A EUROPEAN APPROACH EDITED BY: EUROPEAN CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS E.V. (ECCHR) SECOND EDITION 4 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS 09 PREFACE by Manfred Nowak, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture © by European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights e.V. (ECCHR) 13 JUSTICE AND ACCOUNTABILITY IN EUROPE – DISCUSSING Second Edition, Originally published in March 2008 STRATEGIES by Wolfgang Kaleck, ECCHR This booklet is available through the ECCHR at a service charge of 6 EUR + shipping. Please contact [email protected] for more information. 27 THE U.S. PROGRAM OF EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION AND SECRET DETENTION: PAST AND FUTURE Printed in Germany, January 2009 by Margaret Satterthwaite, New York University All rights reserved. 59 PENDING INVESTIGATION AND COURT CASES ISBN 978-3-00-026794-9 by Denise Bentele, Kamil Majchrzak and Georgios Sotiriadis, ECCHR European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) I. The Freedom of Information Cases (USA/Europe) Greifswalder Strasse 4, D-10405 Berlin 59 FOIA Cases in the U.S. Phone: + 49 - (0) 30 - 40 04 85 90 / 40 04 85 91 62 Freedom of Information Cases in Eastern Europe Fax: + 49 - (0) 30 - 40 04 85 92 Mail: [email protected], Web: www.ECCHR.eu II. The Criminal Cases Council: Michael Ratner, Lotte Leicht, Christian Bommarius, Dieter Hummel 68 The Case of Ahmed Agiza and Mohammed Al Zery (Sweden) Secretary General: Wolfgang -

Al-Qaeda & Taliban Unlawful Combatant

AL-QAEDA & TALIBAN UNLAWFUL COMBATANT DETAINEES,..., 55 A.F. L. Rev. 1 55 A.F. L. Rev. 1 Air Force Law Review 2004 Article AL-QAEDA & TALIBAN UNLAWFUL COMBATANT DETAINEES, UNLAWFUL BELLIGERENCY, AND THE INTERNATIONAL LAWS OF ARMED CONFLICT Lieutenant Colonel (s) Joseph P. “Dutch” Bialkea1 Copyright © 2004 by Lieutenant Colonel (s) Joseph P. “Dutch” Bialke I. INTRODUCTION International Obligations & Responsibilities and the International Rule of Law The United States (U.S.) is currently detaining several hundred al-Qaeda and Taliban unlawful enemy combatants from more than 40 countries at a multi-million dollar maximum-security detention facility at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. These enemy detainees were captured while engaged in hostilities against the U.S. and its allies during the post-September 11, 2001 international armed conflict centered primarily in Afghanistan. The conflict now involves an ongoing concerted international campaign in collective self-defense against a common stateless enemy dispersed throughout the world. Domestic and international human rights organizations and other groups have criticized the U.S.,1 arguing that al-Qaeda and Taliban detainees in Cuba should be granted Geneva Convention III prisoner of war (POW)2status. They contend broadly that pursuant to the international laws of armed conflict (LOAC), combatants captured during armed conflict must be treated equally and conferred POWstatus. However, no such blanket obligation exists in international law. There is no legal or moral equivalence in LOAC between lawful combatants and unlawful combatants, or between lawful belligerency *2 and unlawful belligerency (also referred to as lawful combatantry and unlawful combatantry). -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

20121211 IACHR Petition FINAL

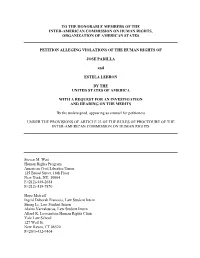

TO THE HONORABLE MEMBERS OF THE INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS, ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES PETITION ALLEGING VIOLATIONS OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF JOSE PADILLA and ESTELA LEBRON BY THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA WITH A REQUEST FOR AN INVESTIGATION AND HEARING ON THE MERITS By the undersigned, appearing as counsel for petitioners UNDER THE PROVISIONS OF ARTICLE 23 OF THE RULES OF PROCEDURE OF THE INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Steven M. Watt Human Rights Program American Civil Liberties Union 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY, 10004 F/(212)-549-2654 P/(212)-519-7870 Hope Metcalf Ingrid Deborah Francois, Law Student Intern Sheng Li, Law Student Intern Alaina Varvaloucas, Law Student Intern Allard K. Lowenstein Human Rights Clinic Yale Law School 127 Wall St. New Haven, CT 06520 P/(203)-432-9404 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................ 3 I. Petitioner Estela Lebron ............................................................................................................................................. 3 II. Seizure, Detention, and Interrogation of Jose Padilla ................................................................................... 3 A. Initial Arrest and Detention Under the Material Witness Act ......................................................... -

Should Lawyers Be Permitted to Violate the Law?

MILITARY LAWYERING AT THE EDGE OF THE RULE OF LAW AT GUANTANAMO: SHOULD LAWYERS BE PERMITTED TO VIOLATE THE LAW? Ellen Yaroshefsky* I. INTRODUCTION “Where were the lawyers?” is the familiar refrain in the legal profession’s reflection on various corporate scandals.1 What is the legal and moral obligation of lawyers who have knowledge of ongoing illegality and criminal behavior of their clients? What should or must those lawyers do? What about government lawyers who have knowledge of such behavior? This Article considers that question in the context of military lawyers at Guantanamo—those lawyers with direct knowledge of the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo, treatment criticized throughout the world as violative of fundamental principles of international law. In essence, where were the lawyers for the government and for individual detainees when the government began to violate the most fundamental norms of the rule of law? This Article discusses the proud history of several military lawyers at Guantanamo who consistently demonstrated an unwavering commitment to the Constitution and to the rule of law. They were deeply offended about the actions of the government they served as it undermined the fundamental premises upon which the country was formed. Their jobs placed them at the edge of the rule of law and caused consistent crises of conscience.2 These military lawyers typically are not * Clinical Professor of Law and Director of the Jacob Burns Ethics Center at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. Sophia Brill, a brilliant future law student, deserves significant credit for her invaluable work on this Article. -

Download Article

tHe ABU oMAr CAse And “eXtrAordinAry rendition” Caterina Mazza Abstract: In 2003 Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr (known as Abu Omar), an Egyptian national with a recognised refugee status in Italy, was been illegally arrested by CIA agents operating on Italian territory. After the abduction he was been transferred to Egypt where he was in- terrogated and tortured for more than one year. The story of the Milan Imam is one of the several cases of “extraordinary renditions” imple- mented by the CIA in cooperation with both European and Middle- Eastern states in order to overwhelm the al-Qaeda organisation. This article analyses the particular vicissitude of Abu Omar, considered as a case study, and to face different issues linked to the more general phe- nomenon of extra-legal renditions thought as a fundamental element of US counter-terrorism strategies. Keywords: extra-legal detention, covert action, torture, counter- terrorism, CIA Introduction The story of Abu Omar is one of many cases which the Com- mission of Inquiry – headed by Dick Marty (a senator within the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) – has investi- gated in relation to the “extraordinary rendition” programme im- plemented by the CIA as a counter-measure against the al-Qaeda organisation. The programme consists of secret and illegal arrests made by the police or by intelligence agents of both European and Middle-Eastern countries that cooperate with the US handing over individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities to the CIA. After their “arrest,” suspects are sent to states in which the use of torture is common such as Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Jor- dan, Uzbekistan, Somalia, Ethiopia.1 The practice of rendition, in- tensified over the course of just a few years, is one of the decisive and determining elements of the counter-terrorism strategy planned 134 and approved by the Bush Administration in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 attacks.