Food Act Report 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic Gaming Machines Strategy 2015-2020

Electronic Gaming Machines Strategy 2015-2020 Version: 1.1 Date approved: 22 December 2015 Reviewed: 15 January 2019 Responsible Department: Planning Related policies: Nil 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................. 3 2 Definitions ............................................................................................................. 3 3 Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 5 4 Scope .................................................................................................................... 5 5 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 6 Gambling and EGMs in the City of Casey ........................................................... 6 7 City of Casey Position on Electronic Gaming Machines ................................... 7 7.1 Advocacy & Partnerships ....................................................................................... 7 7.2 Local Economy ....................................................................................................... 8 7.3 Consultation & Information Provision ...................................................................... 9 7.4 Community Wellbeing ............................................................................................ 9 7.5 Planning Assessment .......................................................................................... -

7.5. Final Outcomes of 2020 General Valuation

Council Meeting Agenda 24/08/2020 7.5 Final outcomes of 2020 General Valuation Abstract This report provides detailed information in relation to the 2020 general valuation of all rateable property and recommends a Council resolution to receive the 1 January 2020 General Valuation in accordance with section 7AF of the Valuation of Land Act 1960. The overall movement in property valuations is as follows: Site Value Capital Improved Net Annual Value Value 2019 Valuations $82,606,592,900 $112,931,834,000 $5,713,810,200 2020 Valuations $86,992,773,300 $116,769,664,000 $5,904,236,100 Change $4,386,180,400 $3,837,830,000 $190,425,800 % Difference 5.31% 3.40% 3.33% The level of value date is 1 January 2020 and the new valuation came into effect from 1 July 2020 and is being used for apportioning rates for the 2020/21 financial year. The general valuation impacts the distribution of rating liability across the municipality. It does not provide Council with any additional revenue. The distribution of rates is affected each general valuation by the movement in the various property classes. The important point from an equity consideration is that all properties must be valued at a common date (i.e. 1 January 2020), so that all are affected by the same market. Large shifts in an individual property’s rate liability only occurs when there are large movements either in the value of a property category (e.g. residential, office, shops, industrial) or the value of certain locations, which are outside the general movements in value across all categories or locations. -

Where the Temples Meet the Sea

ISSN 1442-: Ii ii\ WHERE THE TEMPLES MEET THE SEA.... ¡MietV v L,A I ^ il TORO. s "The turf conditions on Pi courscs have hecn enhanced by uttin for many years. We 're confident Toro 's innovation and leadership u iff provide the best turf solutions for th 1QQQ U.S. Open and beyond. —BraJ G. Kocher Director of Golf Course Maintenance for Pinehurst Resort and Country Club When it comes to large ductivity at its peab and scale cutting coverage, ensure quality of cut no one offers solutions wi th the results you like Toro. With need. SReelmaster® fairway And on Iv To ro can bring mowers from which to you Total bolutions, our choose, you'll he assured customized program the right for machine offering a complete your climate and grass range of products, ser- type. vices and irrigation, Bached hy more than 80 individually designed to years of experience, Toro me et the specitic needs offers the perfect combi- of your course. nation of precision per- Toro. Wh en you demand formance in an easy-to- quality, precision and use machine. Our proven reliability. reliability will beep pro- To finti your nearest Toro Dealer, please telephone 131 388. Toro Commercial Kt/uipment. 59 Woodlands Drive. Braeside Vie 3195. Phone (03) 9580 7355 Fax (03) 9580 7399. Offices in Sydney; Melbourne, Perth. Brisbane. Head Office. Toro Australia Pty Limited, 53 Howards Road, Beterley SA 5009. Phone (08) 8300 36.13 Fax (08) 824.12940. " 1 with Jacklin' Seed and BEST® Fertiliser For over 60 years Jacklin Seed and BEST fertilisers have built strong reputations in the turf- grass industry. -

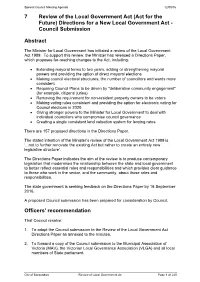

(Act for the Future) Directions for a New Local Government Act - Council Submission

Special Council Meeting Agenda 12/09/16 7 Review of the Local Government Act (Act for the Future) Directions for a New Local Government Act - Council Submission Abstract The Minister for Local Government has initiated a review of the Local Government Act 1989. To support this review, the Minister has released a Directions Paper, which proposes far-reaching changes to the Act, including: Extending mayoral terms to two years, adding or strengthening mayoral powers and providing the option of direct mayoral elections Making council electoral structures, the number of councillors and wards more consistent Requiring Council Plans to be driven by "deliberative community engagement" (for example, citizens' juries) Removing the requirement for non-resident property owners to be voters Making voting rules consistent and providing the option for electronic voting for Council elections in 2020 Giving stronger powers to the Minister for Local Government to deal with individual councillors who compromise council governance Creating a single consistent land valuation system for levying rates There are 157 proposed directions in the Directions Paper. The stated intention of the Minister’s review of the Local Government Act 1989 is ‘...not to further renovate the existing Act but rather to create an entirely new legislative structure’. The Directions Paper indicates the aim of the review is to produce contemporary legislation that modernises the relationship between the state and local government to better reflect essential roles and responsibilities and which provides clear guidance to those who work in the sector, and the community, about those roles and responsibilities. The state government is seeking feedback on the Directions Paper by 16 September 2016. -

Response to Infrastructure Victoria's Draft 30-Year Infrastructure Strategy

Response to Infrastructure Victoria’s Draft 30-year Infrastructure Strategy February 2021 1 Contents Response to Infrastructure Victoria’s Draft 30-year Infrastructure Strategy ........................... 3 Overview ........................................................................................................................... 3 Top 10 Local Government Areas in Victoria for Homebuilder applications ..................... 3 Summary of Metropolitan Fringe Growth Areas,2014-2019, Victoria .............................. 4 Summary of Metropolitan Fringe Growth Areas,2021-2031, Victoria .............................. 4 Covid 19 has impacted heavily on growth area communities ............................................. 5 Infrastructure demand in Melbourne’s growth areas is long term ....................................... 5 Investment in Growth areas is an economic opportunity .................................................... 6 Victoria lacks place-based infrastructure planning and delivery which results in poor outcomes ........................................................................................................................... 6 NGAA Response to specific sections and recommendations ............................................. 7 Section 1.4 Stay connected to global markets ................................................................ 7 Section 2.1 Integrate land use and infrastructure planning. ............................................ 7 Section 2.2 Create thriving urban places ....................................................................... -

To View Asset

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT 2001 ANNUAL REPORT This report outlines the achievements of the Department of Natural Resources and Environment during 2000-01 from left to right: The Hon Candy Broad MLC The Hon Keith Hamilton MLA The Hon Sherryl Garbutt MLA The Hon Sherryl Garbutt MLA Minister for Environment and Conservation The Hon Keith Hamilton MLA Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs The Hon Candy Broad MLC Minister for Energy and Resources Dear Ministers In accordance with the Financial Management Act 1994, I am pleased to submit to you the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Annual Report for the year ending 30 June 2001. Yours sincerely Chloe Munro Secretary The Annual Report is available on NRE’s website at www.nre.vic.gov.au © The State of Victoria, Department of Natural Resources and Environment, 2001. ISSN No 1327-6344 Published by the Victorian Government Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia October 2001 Front cover photo – remote control channel along Meribein irrigation system. The gate uses state of the art computer technology to regulate water flow according to user requirements Photography by Megan Jones DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT OUR VISION OUR VALUES OUR OUTCOMES PROSPERITY OUR ORGANISATIONAL VALUES • Ecologically sustainable WITH CARE REFLECT OUR ATTITUDES development TO THE COMMUNITY, OUR • Enhanced biodiversity values SERVICES, OUR BUSINESS • Improved natural OUR PURPOSE AND EACH OTHER. WE: resource -

Wyndham City Plan 2017-21 Contents

Wyndham City Plan 2017-21 Contents 04 05 06 07 Bo undary Rd Boundary Rd d R t i e n y r w a F T s ce d Harrison n ri We R P t rribee Rive Sayers Rd u m i r r e D r Hogans Rd d R s i r r o M y Iramoo Hw S d haws Rd Princes R d k R o o s t y t C e t k n i Point Cook c o Princes Fw a P Homestead Rd H We rribee River Aviation Rd y w s F ce rin P Your Councillors Message from Ward Map Wyndham City the Mayor & CEO Profile Towards Wyndham 2040: 08 12 17 20 City Plan 2017-2021 A place for people Wyndham City acknowledges that Aboriginal people have lived in this area Community Our Vision for Our Vision for Our Vision for for over 60,000 years. The Werribee River has been a significant meeting Engagement People and Places and Spaces Earning and place for its first custodians, the peoples of the Kulin Nation. Community Learning 24 28 29 30 For a diversity of Aboriginal peoples who have moved here from around Australia, it is a centre of economic activity and a place to build community. In this way Wyndham has always been a place for people. The Wyndham To see an interactive digital City Statement of Commitment provides a set of principles that underscore version of this Plan visit: how Council commits to work with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in www.wyndham.vic.gov.au/ Our Vision for Council’s Planning Council’s Reporting Endnotes Leadership and Framework Framework the context of Reconciliation. -

Reform of the Psychiatric Disability Rehabilitation and Support Services Program

Mental Health Community Support Services June 2014 Fact Sheet 2: Information for Existing Clients Fact Sheet: Information for Existing Clients This fact sheet provides information for current clients of mental health community support services provided under the Victorian Psychiatric Disability Rehabilitation and Support Services (PDRSS) program. It includes information about the changes that will happen to these services over the next few months, when these changes will occur and how the changes might affect you. As part of these changes the Victorian Government will also change the name of the PDRSS program to Mental Health Community Support Services (MHCSS) program from August 2014. This change is about supporting you. The changes will ensure access to mental health community support services is fair and equitable by ensuring people most disabled by their mental health condition do not miss out on the support they need. The reforms will make it easier for new and returning consumers and carers to get help no matter where they live. This will be achieved by establishing a centralised intake point for all referrals in each local area. A fact sheet explaining how the new intake assessment system will work will be made available shortly. We also know you want services to be of a consistent quality and designed around your individual needs and preferences. This is why we are introducing Individualised Client Support Packages. They will replace standard, moderate and intensive Home Based Outreach Services, Day Programs, Care Coordination, Aged Intensive Program and Special Client Packages from 1 August 2014. Your support package will help you to develop the life skills needed to live well in the community and to manage your mental illness. -

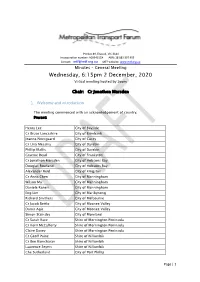

Wednesday, 6:15Pm 2 December, 2020 Virtual Meeting Hosted by Zoom

PO Box 89, Elwood, VIC 3184 incorporation number: A0034315X ABN: 18 683 397 905 Contact: [email protected] MTF website: www.mtf.org.au Minutes – General Meeting Wednesday, 6:15pm 2 December, 2020 Virtual meeting hosted by zoom Chair: Cr Jonathon Marsden 1. Welcome and introduction The meeting commenced with an acknowledgement of country. Present: Henry Lee City of Bayside Cr Bruce Lancashire City of Brimbank Joanna Noesgaard City of Casey Cr Lina Messina City of Darebin Phillip Mallis City of Darebin Graeme Read City of Frankston Cr Jonathon Marsden City of Hobsons Bay Douglas Rowland City of Hobsons Bay Alexander Reid City of Kingston Cr Anna Chen City of Manningham Wilson Ma City of Manningham Daniele Raneri City of Manningham Eng Lim City of Maribynong Richard Smithers City of Melbourne Cr Jacob Bettio City of Moonee Valley Damir Agic City of Moonee Valley Simon Stainsby City of Moreland Cr Sarah Race Shire of Mornington Peninsula Cr Kerri McCafferty Shire of Mornington Peninsula Claire Davey Shire of Mornington Peninsula Cr Geoff Paine Shire of Nillumbik Cr Ben Ramcharan Shire of Nillumbik Lawrence Seyers Shire of Nillumbik Che Sutherland City of Port Phillip Page | 1 Oliver Stolz City of Port Phillip Tim Lecky City of Stonnington Serman Uluca City of Whitehorse Russell Trickner City of Whittlesea Troy Knowling City of Whittlesea Melissa Falkenberg City of Wyndham Cr Gabrielle DeVietri City of Yarra Julian Wearne City of Yarra Geoff Oulton Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) David Stosser MRCagney Consulting Justin Rogers TransDev Greg Day Edunity Jane Waldock MTF Apologies: Cr Edward Crossland - Yarra Frank Vassilacos - Manningham Sam Romaszko - Melton Cr Josh Fergeus - Monash Gael Reid - Boroondara Chloe Wright - Yarra Ross Evans - Monash John Bartels – Port Phillip Cr Victor Franco - Boroondara Cr Bob Turner - Melton Cr Jim Magee – Glen Eira Vanessa Petrie - Darebin Cr Tom Melican - Banyule 2. -

Various Planning Schemes Combined 3 May 2021

Form 1 Section 38(1) NOTICE OF APPROVAL OF AMENDMENT TO A PLANNING SCHEME TO BE PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT On 29 April 2021 the Minister approved Amendment C378melb to the Melbourne Planning Scheme. The amendment was prepared by Minister for Planning. The Melbourne City Council will be responsible for administering the scheme. The amendment applies the Environmental Significance Overlay - Schedule 2 to protect trees identified as significant in the Exceptional Tree Register 2019 on an interim basis until 27 April 2023. The Minister exempted the Minister from the requirements of section 17, 18 and 19 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 being the requirement to: Give a copy of the amendment, together with the explanatory report and any document applied, adopted or incorporated in the amendment to the relevant municipal council. Make the amendment available for inspection until the amendment is approved. Give notice of the amendment to every Minister, public authority and municipal council that the planning authority believes may be materially affected by the amendment Give notice of the amendment to the owners and occupiers of land that the planning authority believes may be materially affected by the amendment. Give notice of the amendment to any Minister, public authority, municipal council or person prescribed. Publish a notice of the amendment in a newspaper generally circulating in the area. Publish a notice of the preparation of the amendment in the Government Gazette. The Minister exempted Minister for Planning from the requirements 6 and 7 of the Planning and Environment Regulations 2015 being the requirement for the purposes of giving notice of an amendment in accordance with section 19 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. -

City of Wyndham Review of Heritage Sites of Local Interest

CITY OF WYNDHAM REVIEW OF HERITAGE SITES OF LOCAL INTEREST PETER ANDREW BARRETT Architectural Historians and Conservation Consultants August 2004 City of Wyndham Review of Heritage Sites of Local Interest CITY OF WYNDHAM REVIEW OF HERITAGE SITES OF LOCAL INTEREST Cover photograph: Looking west from the mouth of the Werribee River, Werribee South. The You Yangs, visible in the distance, form a backdrop to the rolling plains of Wyndham. peter andrew barrett architectural historians and conservation consultants City of Wyndham Review of Heritage Sites of Local Interest CITY OF WYNDHAM REVIEW OF HERITAGE SITES OF LOCAL INTEREST Prepared by PETER ANDREW BARRETT Architectural Historians and Conservation Consultants Suite 708, 31 Spring Street, Melbourne Telephone: 9639 2646 August 2004 peter andrew barrett architectural historians and conservation consultants City of Wyndham Review of Heritage Sites of Local Interest Contents 1.0 Introduction 4 2.0 Consultants 4 3.0 Acknowledgements 4 4.0 Methodology 4 5.0 Constraints 5 6.0 Findings 5 7.0 Recommendations and Conclusions 7 8.0 Data Sheets 8.1 Melbourne-Geelong Railway Line 9 8.2 Hoppers Crossing 23 8.3 Laverton North 34 8.4 Little River 37 8.5 Mambourin 55 8.6 Tarneit 58 8.7 Truganina 120 8.8 Werribee 146 8.9 Werribee South 201 8.10 Wyndham Vale 231 Bibliography 237 Appendix A: Index of sites by place name 241 Appendix B: Index of sites by location 246 Appendix C: List of sites that could not be located 251 3 peter andrew barrett architectural historians and conservation consultants City of Wyndham Review of Heritage Sites of Local Interest 1.0 Introduction The ‘City of Wyndham Review of Heritage Sites of Local Interest’ was commissioned by the Wyndham City Council in early 2004. -

An Interesting Point © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This Work Is Copyright

AN INTERESTING POINT © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Cover Image: ‘Flying Start’ by Norm Clifford - QinetiQ Pty Ltd National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Campbell-Wright, Steve, author. Title: An interesting point : a history of military aviation at Point Cook 1914-2014 / Steve Campbell-Wright. ISBN: 9781925062007 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aeronautics, Military--Victoria--Point Cook--History. Air pilots, Military--Victoria--Point Cook. Point Cook (Vic.)--History. Other. Authors/Contributors: Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. Dewey Number: 358.400994 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre F3-G, Department of Defence Telephone: + 61 2 6128 7041 PO Box 7932 Facsimile: + 61 2 6128 7053 CANBERRA BC 2610 Email: [email protected] AUSTRALIA Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower AN INTERESTING A History of Military Aviation at Point Cook 1914 – 2014 Steve Campbell-Wright ABOUT THE AUTHOR Steve Campbell-Wright has served in the Air Force for over 30 years. He holds a Masters degree in arts from the University of Melbourne and postgraduate qualifications in cultural heritage from Deakin University.